It’s never a good look to admit to partiality. It belies the pretense of objectivity upon which criticism rests its dubious authority and inevitably fesses up to all those aspects of personality—of affiliations, animosities, and myriad other vested interests—that make culture something far less of a fair playing field and rather more like a social blood sport. Mike Osterhout brings this to mind not simply because he had the temerity years ago to curate a show called Nepotism making the machinations of friendship and community so explicit that it was, at the time, the only exhibition ever at the August old alternative space that put it on to be denied all funding, but because, well, for whatever reasons I can barely fathom, he is among my very favorite artists.

For the decades now that I have closely followed his art and done my useless best to tell others about it, I’ve taken an unhealthy pleasure in his misery, enjoying his cult-like status among far-flung generations of musicians and artists who appreciate his weirdness and respect his uncompromising purity, as well as feeling my epic faith in his genius somehow ratified by the fact it has been so consistently overlooked. As many we know and support have gone on to be art stars, and many more have folded up their tents and reinvented themselves in fields where creativity does not entail dealing with the art world, Osterhout’s perseverance has been nothing less than astounding, responding to the ongoing ignominy of being ignored by producing evermore work and pushing it all so much further. Perhaps it is because he reminds me of what we thought all those years ago when we were young, that success, fame, and fortune were indeed signifiers of something truly lame and compromised, or maybe it is because I understand his failures to be very much my own. If only I could have explained his work better to people surely they would have gotten it. That, alas, would have entailed me actually understanding his work as much as I appreciate it, and while every little bit of it is fully intelligible, the real grace of his practice is that in its entirety it is quite inexplicable. I’ll never give up on believing in Mike Osterhout as an artist, but at least here and now I’ll let him explain himself for a change.

So you’re in Sullivan County, back where you first started as a kid, but there’s a lifetime in between—you kind of had to have your early life fall apart and fall away first before becoming a conceptual artist in San Francisco, and then a tenure as part of the East Village scene in New York, before coming back up here. How did that work out?

Well, it’s still working out. I think all artists have a tendency to step away from early influences, only to come back and reassess them later in one’s career. I grew up very small town, detached from the intellectual world, and completely oblivious to what art was, or could be. Music was a big influence. I went to Woodstock as a 16-year-old kid. But I knew very little about visual art, and absolutely nothing of conceptualism. San Francisco introduced me to that and New York introduced me to the “art world.” And now, some 40 years later, I’m back in the sticks trying to make sense of all the steps and missteps.

As unlikely as it would seem for a connection to exist between the Bay area conceptualism of the late-seventies, the market-based social economies of the New York art world, and now this rural incarnation of your art over the past 20 years, these different bodies of work you produced fit pretty well together. I think of all your projects as being cut from the same cloth, such as creating a whorehouse or buying a cow and branding it with your art in San Francisco, then setting up both a conceptual art gallery and a migratory performance art church in New York, to now owning and operating the oldest church in your county and repurposing an old synagogue as your studio.

I guess that’s part of my unconscious methodology. Threads run through all that work. The thread of the institution is an important one. I’ve always liked to fuck with religious, academic, and even business institutions. The first church I did in San Francisco was a one-night performance with a hired Black minister who had had himself crucified in a park in Oakland. A year later, I did a one-night brothel at the same location. MO David Gallery started in San Francisco then moved to New York, only to close in 1986 and reopen as MO David North in 2010. These themes can take twists and turns, so that going to seminary seems as legit as running a brothel or singing in a rock band. I want the work to reflect an honesty, knowing that I can stop at any time and move on to something completely new I never would’ve considered previously.

I like how you describe your path as a series of “steps and missteps.” It’s not like that old canard about how great art always has the inherent chance of failure, which is certainly true, but kind of how all your genius is also very much a total folly. I’m pretty sure not any of the three incarnations of your gallery made what could be called a profit, and quite sure that you would be the only cat who ever lost money doing a whorehouse, so it’s like all your schemes manifest themselves as art through their incapacity as business. The same way you make your congregation each burn a dollar bill to enter your church, rather than levying a more practical tithe, it seems equally appropriate that your master plan to bottle water out of a local spring and market it as “holy water” from your church is brilliant precisely because it didn’t really work.

Do you think then, in your address of institutions, that your work needs modesty or even a degree of ridiculousness to subvert the authority we otherwise too easily invest in churches, galleries, and the enterprise of business?

Yes, most definitely. The failure that occurs, whether purposefully intended or not, subverts the project in a way that, I’m sorry to say, elevates it as art. Who cares about another successful business? When I begin any of these works, like the holy water or the gallery, my hope is to make money. The problem is I’m way better at making art than succeeding in business on almost any level. Slowly I’m realizing this. It’s taken years. My father was a stockbroker, and quite a good businessman. I used to think I had inherited a little of his business savvy. Finally I’m admitting that I have none.

On the other hand, the Church of the Little Green Man was set up to burn dollar bills from day one. The subversion was inherent in the project from the beginning. It’s the glue that has kept us together for 30 years. We are a congregation of modest means. If we had ever charged to get in the door, we would have imploded in petty in-fighting greed over $20, years ago. That burning dollar bill keeps us going. I’m not immune to “market envy,” but for now I’ve promised myself not to come up with anymore crackpot “business ideas.”

Mike Osterhout, HOLYLGM WATER. Courtesy of the artist.

Mike Osterhout, CLGM BAPTISM, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Maybe you didn’t inherit your father’s financial savvy, but you did inherit some perverse interest in terms of business. Lots of artists today think of their job as a business, but I rather prefer how your ideas on business are more like conceptual art. As far as parental legacies, however, there might be something to be said for the abject ineptitude of your dad’s passion as a handyman. You may have real high-end skills in carpentry that would not compare with your father’s less accomplished and utterly stubborn efforts in that regard, but I like to think your insane and often hilarious sculptural combines share something of this visionary streak with the DIY hobbyist.

One of the classic stories of my old man was of him taking back a brand new drill he bought at the local hardware store. He’d tried for an hour to drill a hole to no avail. He took it back, pissed. “This thing’s no good,” he barked at the counter boy. The kid looked at the drill and clicked the button behind the trigger. My father had had the drill in reverse the whole time. Some days that’s just how I feel—like the fucking drill is in reverse. I blow the engine on the car and then fill it with concrete. My old man is turning over in his grave.

That’s a great one and it kind of reminds me of the first piece you see going to your synagogue/studio: a cylindrical metal tube protruding from a hole in the front door that reveals itself once you open the door to be the front of a shotgun barrel.

Of course what made it all so funny with your dad and the broken drill was the blustery confidence he brought to these things. The way you approach your projects—the demented ambitions you dream for them all—has a bit of that as well, but it seems the wisdom in your art always comes about from maintaining a contrary position of not knowing.

I think one of the greatest perks of being an artist is admitting just how little you know. It gives you such freedom in a world that wants everyone to be a goddamn expert. I’ve never much known what I was doing. Even when I professed to be a so-called expert, it was pure bullshit. I went to seminary knowing nothing of religion, yet it gives me a certain cred to say I studied theology. It’s all smoke and mirrors. That’s why I loved punk rock—it embraced the non-talented. Attitude was everything. Modesty comes from admitting just how limited you are. Artists are basically impotent. The ones who think they are really making a difference in the world at large are delusional and usually not very interesting.

Mike Osterhout, POINT BLANK, 2014. 12 gauge shotgun installed in shut door. Courtesy of the artist.

So true, but your befuddlement is truly unique. So much of art depends on a pretense that is utterly arrogant. To hear Koons describe his art as if his interrogation of the mundane is in direct communication with God and the sublime and then to think about how you transform the mundane through the sheer whimsy of an uncanny oddity is to appreciate the very real difference between your not-knowing and the mighty unknown that has been a kind of Manifest Destiny in American art since abstract expressionism.

To recognize how punk’s rank amateurism has been a major impetus for much of your oeuvre is spot on. So what your work may lack in arrogance we can say it more than makes up for in attitude. As you’ve become less of a performance artist than one who makes stuff, the punk attitude remains. Where before you would give out cocaine on a spoon as a sacrament or burn flags as a sacrifice in your church, it seems that destroying a perfectly good car and then filling it with concrete instead of properly junking it for parts and scrap, pointing a shotgun out the door of your studio, or installing a stripper pole in your church are equally thorny gestures, what we would have to call irascible objects.

I think what you mean to say is that my fucked up performances seemed to have transformed into fucked up objects. I’ll cop to that. It’s still all about relationship. I didn’t start out wanting to do a car piece. I KILLED SHIRLEY is the very unintentional and rather stupid blowing of my car’s engine by not checking the oil. The car is a 2002 Chrysler Sebring convertible. I named her “Shirley.” I loved her. It made no sense financially to put a new engine in this car, so instead of scrapping her I entombed her in concrete, turning her into an object. A lot of my work deals with death, or simply endings. I bought and branded a cow, only to have her get out on the road and get hit by a truck. I then turned the steaks into objects. The fake German painter Kristan Kohl, who I still use to do canvas work, was purposefully “killed off” in 1984, only to have her continue working.

Nowadays I’m being influenced by the rather depressive, and at times aggressively anti-aesthetic environment of Hasidic/hillbilly Sullivan County. Works like WHEEL BARROW HENGE (a circle of broken wheel barrows around the church) reflect the landscape all around me. The only thing that sets this apart from my scrappy neighbor’s yards is the formalized circle and sheer number of broken, rusted objects. I love to walk that edge, not by hoarding or fueling some advanced case of horror vacui, but by setting forth a specific work of retired workman’s tools, or a hay wagon turned lion cage. Most times they don’t even read as art. And that’s fine with me.

I KILLED SHIRLEY, 2015. Concrete in ‘02 Chrysler Sebring. Courtesy of the artist.

Mike Osterhout, FOR SALE, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Hasidic and hillbilly, as you must rightly call it—your province is also more commonly known as the Borscht Belt, the historical seat of lowbrow Jewish American entertainments that fundamentally changed our popular culture. Probably its biggest and most enduring impact has been in terms of humor, what we think of as funny, and the way we tell those kinds of jokes, which in Catskills parlance would be called shtick.

A monumental TOTEM OF BRUCE made of stacked mannequins, your LION OF JUDAH CAGE, a billboard that says only FOR SALE, or any of a seemingly vast inventory of assemblage-like combines that exist somewhere between a Duchampian wink and a comedy club groan—they have the whimsy of Bay Area conceptual art, but also a remarkable lack of embarrassment when it comes to playing for laughs. I see you have recently retired your very popular crucified Jesus selfie from the front of your church property. Is it all a matter of aesthetic decisions for you or do you have to take some measure to make sure things are never too smart or too silly?

I remember Tom Marioni, a Bay Area artist you wouldn’t normally associate with humor, stating, “I take my jokes seriously.” That kind of sums up my approach to absurdity in my work. The conceptualism of Howard Fried, Chris Burden, and even Linda Montano employed humor with a light touch. Devouring their work in the late-‘70s, as I was just beginning to mature as an artist, gave me permission to laugh at how ridiculous the entire process of being an artist really was. Then, when I moved to New York, the artists seemed a little too serious and full of themselves. Of course there were exceptions like Robin Winters and Les Levine, but on the whole, humor in art, as in music, tends to get relegated to the novelty bin.

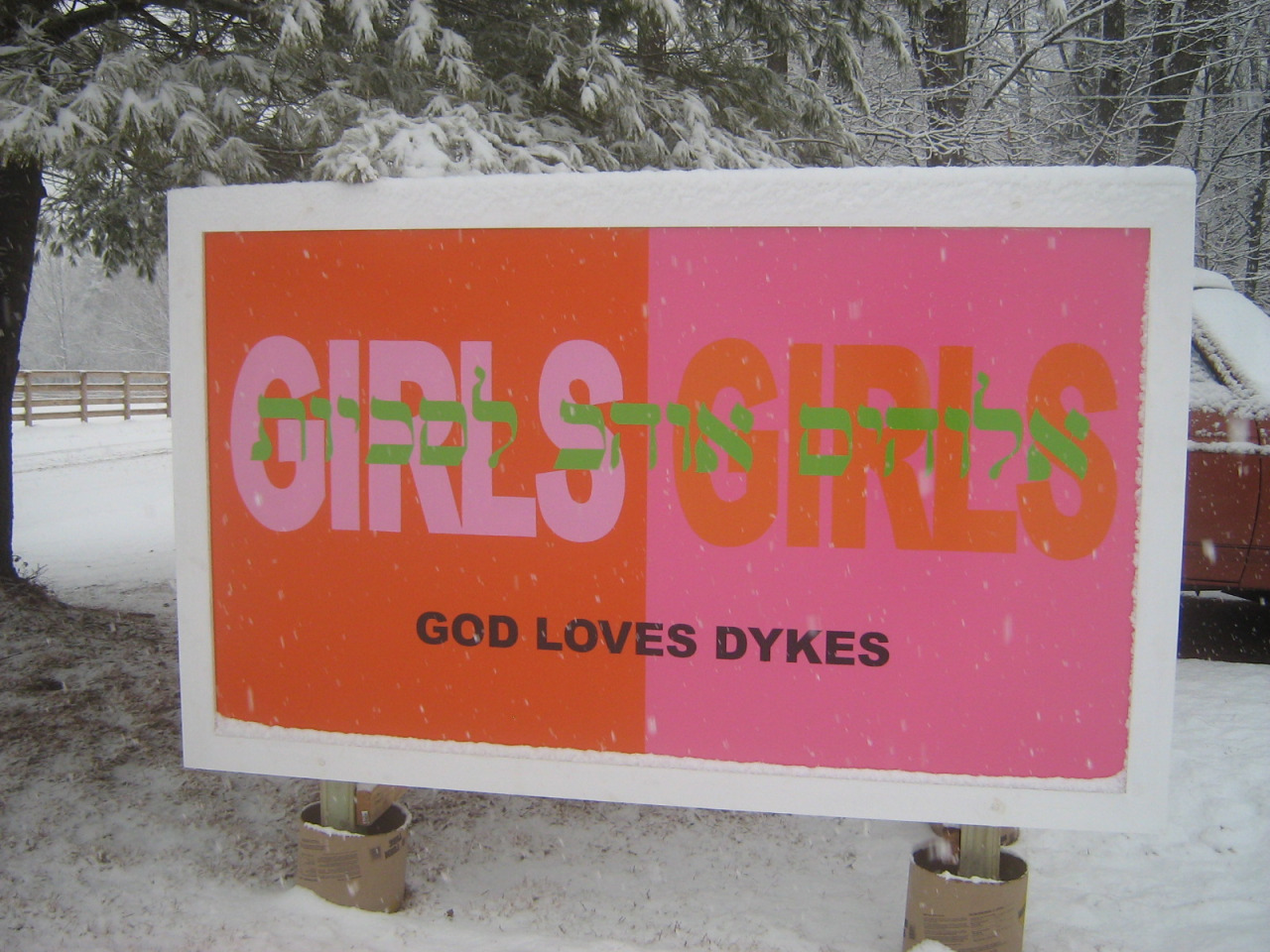

In the Catskills it’s a completely different story. There is no art world, but like you said, there is an incredible history of shtick. At first I kept a low profile with my work, but after years of producing and not showing I decided to pepper my churchyard with increasingly large constructions. It was a little like doing street art, but since I owned the property no one could make me remove anything. Initially, it had a bit of a roadside attraction aspect that I exploited. GOD LOVES FAGS (and GOD LOVES DYKES) was echoed in Hebrew on large billboards next to a large steel $ORRY sculpture. CRUCIFY THY SELFIE was patterned after those hokey tourist facades where you stick your head in the hole on top of a pilgrim or Indian and take a picture. But space is limited, so I do rotate the crops in the sculpture garden, making room for new work. I have to admit CRUCIFY THY SELFIE, although a hit with the public, was a bit too carnivalesque and “silly” for my taste. So into storage it went. I don’t know about work being “too smart.” I can’t say that’s ever happened.

Mike Osterhout, GOD LOVE DYKES, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Mike Osterhout, GOD LOVES FAGS, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Your great remove from the city, to be honest, is less than a hundred miles away, so this critical distance is perhaps just as perceptual as it is physical. You take the isolation into your work, but you do so with a great deal of social engagement that relies deeply on an extended community of fellow New York dropouts around you. How does distance and proximity work for you? You have all these hipster urban kids and successful artists who are into what you’re doing, but you also do things like create art out of your deer and turkey hunting, even including animal parts in your pieces, that just don’t fit in with the culture and politics of the art world.

I stepped away from the art world long before I left the city. Forming the rock band Purple Geezus and the Church of Little Green Man almost simultaneously, while still living in the East Village, had a big effect on me as an artist. I considered these activities sculptural, but never really felt the need to contextualize them within the gallery environment. It was just pure fun to be a lead singer in a rock band and a “minister” in a crackpot church. So what if the art world didn’t recognize it as such.

One of the last bodies of work that I exhibited in New York was the deconstructed animal pieces. I was living on E7 & Ave. C, but took every opportunity to come upstate and hunt deer and turkey. Once again, I saw the activity of hunting as an extension of a way of working that seemed, at least to me, cohesive. I remember showing this body of work to the artist Mark Flood and having him tell me point blank that no collector would touch this stuff. I’d gone from iconoclastic religious work to painting over other artist’s paintings to now hunting and killing animals at the height of the mid-‘90s PC era. To say it remains problematic to this day would be an understatement. Nonetheless, the activity of hunting informs much of my present day work like the large tobacco leaf paintings and concrete mops. I know I’ve said many times how similar hunting is to art in the way you embrace failure, yet as I’ve become quite a good hunter success has also become a concern. I tend to think there’s nothing more boring than being really good at something. In a perverse way my lack of show career has kept me hungry and willing and able to fuck with the system, unconcerned with the consequences. I have nothing to lose.

The hunting art has been pretty off-putting for many people, but I’d say with somewhat queasy discomfort that some of Beuys’s fat and felt pieces might induce more than the visceral revulsion we’re likely to get with Viennese Actionism. Another outré artist material you use involves blood, and not just the blood prints from the steaks of your cow, but also the human blood prints you pull from your tattoos when they’re still fresh. Again, yours is not nearly as gnarly as a lot of other blood and guts art out there, but it’s such an arch decision to choose stuff like this for your art materials.

Before I moved to the west coast I started out as a printmaker. I loved the physicality of stone lithography in particular. But what I didn’t take to was the anal approach to editions. One print seemed plenty. So when I got my first tattoo in San Francisco and removed the bandage discovering the bloody image on the paper towel I knew I had my technique. This was the late-‘70s, the beginning of the AIDS epidemic. There was an extreme phobia surrounding blood. As an art material it seemed perfect. My first tattoo series was to find 12 people (six men and six women) who had no tattoos, and have them agree to have one of my designs tattooed on their person, pulling prints from each. The tattoo icon Lyle Tuttle did the work and I ended up showing the monoprints at his “tattoo museum” in San Francisco. Over the years I’ve had more print work done on myself than others. If it is a name or a word I have it tattooed backwards in order to get the print to read correctly. The print is more important than reading it on my arm.

As far as the hunting pieces are concerned, I also use deer blood in various ways. My grandfather was a butcher. I knew how to butcher a deer long before I knew how to hunt one. There’s no sensationalism implied in this material. You mentioned Beuys. I’ve always had an affinity for the elegance of his work, no matter what material he chose. Pulling prints from a cow’s nose, a memorial tattoo, or the rib cage of a deer I shot and butchered is a little like pressing flowers in a book: a kind of ongoing journal, far from the shock of the Viennese.

Mike Osterhout, RIBS, 2012. Deer blood on rice paper. Courtesy of the artist.

That’s right, it would be hard find a conceptual artist of your generation who did not have some deep affinity for the work of Beuys—he was such a game changer that way. You even bought an old schoolhouse near your church and ran a summer intensive program in cahoots with the San Francisco Art Institute, and you adopted Beuys concept of “social sculpture” as the primary pedagogy. I can see how you would take to his guiding belief that artists should put their art out into the world as a transformative act, but Beuys’s social sculpture was of course so utopian. It’s not that your art lacks optimism in any way—perhaps it’s almost foolishly hopeful—but it doesn’t go about these things with that same kind of radical certainty and confidence, like it’s too idiosyncratic, frail, and flawed to really try to change the world as Beuys claimed he was doing. I see your art very much as social sculpture, but it does beg the question of what it is really doing out there in our world.

While I was still an undergrad at SFAI, Howard Fried assigned me three artists to do a classroom lecture on: Beuys, Terry Fox, and Les Levine. I knew Terry’s work a little and Beuys hardly at all. The deeper I dug into Beuys the more impressed I was. He was the big voice of that generation of conceptualists, almost a megalomaniac in the way he presented his theories, as well as objects. The confidence was intoxicating. But what was lacking with Beuys and Fox was humor. Les Levine had that in spades. Les and I became friends when I moved MO David to New York in the early-‘80s and I even showed him. Les didn’t lack confidence either, but he had a way of fucking with the system I really liked. He could be smart as well as funny.

THE OLD SCHOOL FOR SOCIAL SCULPTURE took Beuys’s lofty ideals and put them into literal practice. With the help of Tony Labat (an artist I owe a lot to), we established a graduate school program in a one-room schoolhouse. Instead of concentrating on the studio, I brought in a faculty that would discuss strategies for making art. They each took up residence over a 24-hour period, eating, drinking, and hanging out with the students. It was a big hit.

The “world,” as you put it, can be as simple as your front yard, a blog, or a magazine interview. The word “artist” has become so associated with market and “art world,” that it seems to have less and less to do with what I do. Nonetheless, it remains one of the last refuges for all of us admittedly uncertain, flawed fools. I have no intention of changing the world. Utopia never interested me.