Trevor Paglen

September 10 – October 24, 2015

Metro Pictures

519 West 24th Street, New York NY 10011

In his germinal 1957 text, Mythologies, Roland Barthes discusses how systems of power use myth as a way of manipulating public opinion to further agendas of oppression. He states that this process involves rewriting narratives of power to appear as a “natural” occurrence. Through creating myths, and mythologizing the existence of oppression, that which once felt unnatural suddenly becomes the status quo—as if the will of an elite class is as commonplace as seasons changing. In 1957, Barthes cited a variety of dubious large-scale systems of communication (and conditioning), like post-war national news media, for naturalizing myths. Sixty years later, this process continues to thrive within the branding strategies of multi-national corporations and the intelligence community of G8 nations. To that end, Trevor Paglen’s work unravels the myths of our time in order to show that not all things are as natural as they seem.

Trevor Paglen. Installation view, Metro Pictures, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.

Paglen’s exhibition at Metro Pictures explores the tension between natural and unnatural systems through a scrutinizing lens focused on the politics of privacy, network infrastructure, and the military industrial complex. In doing so, Paglen shows audiences that geography is inherently political—how maps, the sea floor, or even remote landscapes in and of themselves contain evidence of pernicious exercises of power. As meaningful and worthwhile as these initial observations are, Paglen’s method of exposure rests on an abstract analysis of the act of looking.

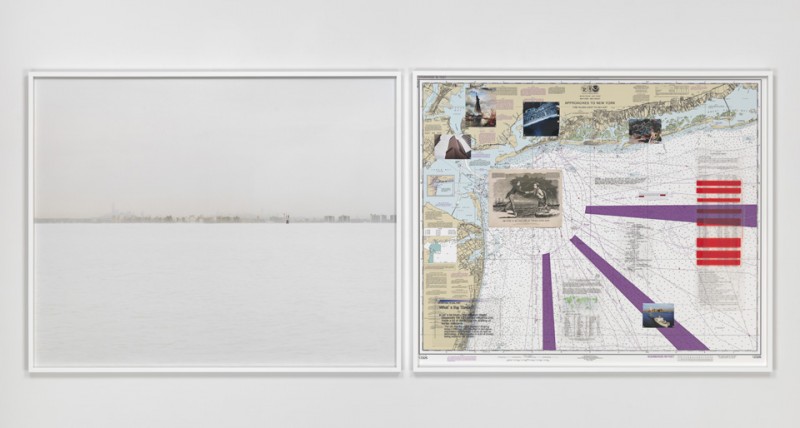

Trevor Paglen. “NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, New York City, New York, United States,” 2015. c-print and mixed media on navigational chart, 48 x 60 inches (c-print), 121.9 x 152.4 cm, 48 x 58 1/2 inches (map), 121.9 x 148.6 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.

Unlike other contemporary artists using photography, Paglen’s abstraction is not based in the formal renegotiation of taking an image or in the conceptual reconfiguration of making photographic material. Paglen’s abstraction is one that stems from a curiosity of looking at something deeply—to probe the unseen, to uncover the nearly invisible, and to pry into unwelcome spaces. It is an investigatory abstraction, one that doesn’t challenge the conventions of photography, but instead reinforces how perspective on any particular subject makes all the difference. In some ways, Paglen’s exhibition is a return to form, leveraging the qualities of a photograph as a medium of critical documentation.

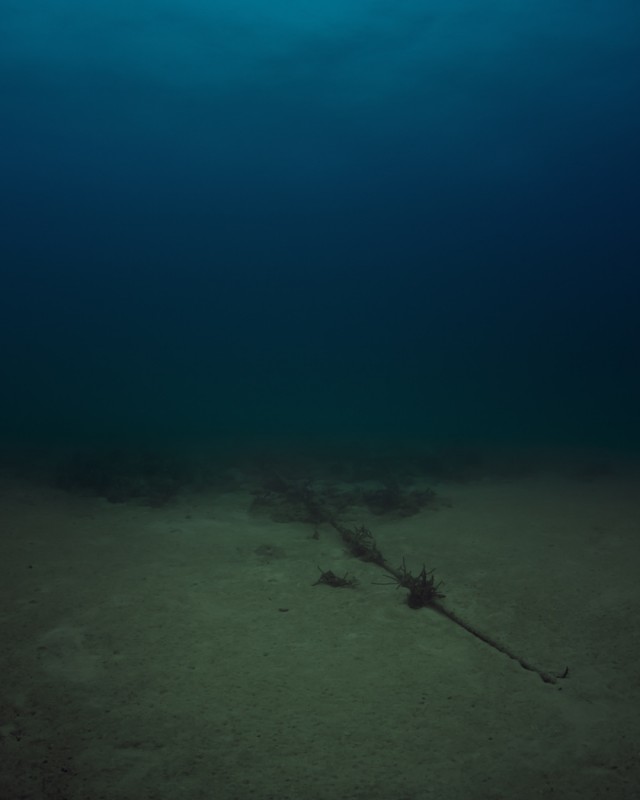

Trevor Paglen. “Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1), NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Atlantic Ocean,” 2015. c-print, 60 x 48 inches, 152.4 x 121.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.

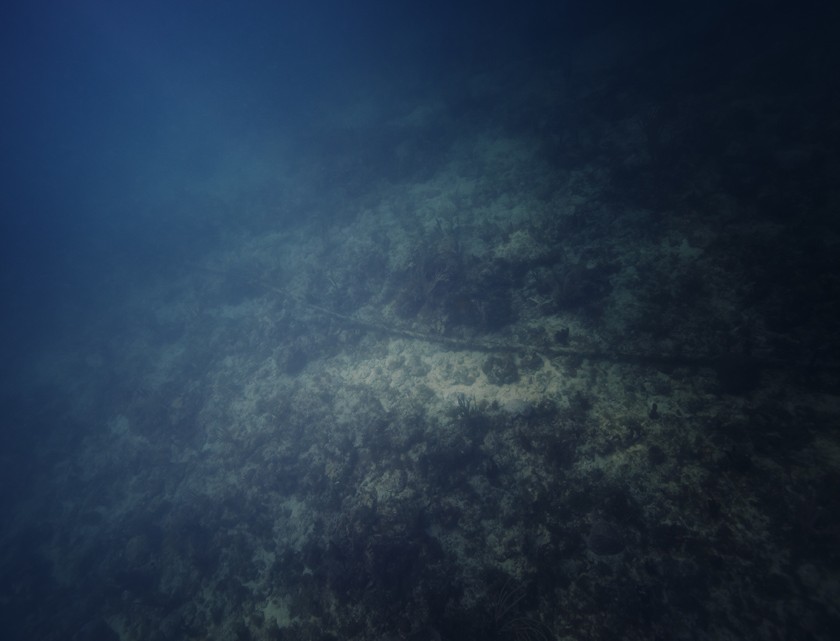

Although some subjects presented in the exhibition are purposefully obfuscated or illegible (as is the case for TOP SECRET, COMINT, STELLAR WIND, NOFORN, [2015]) many of Paglen’s more effective works involve objects and scenarios of some degree of familiarity. Perhaps a better way of phrasing this is to avoid asking what it is that we’re looking at, but rather wondering why it is significant to represent. In a new series of photographs, Paglen creates haunting and densely dark “portraits” of submarine network cabling monitored by the NSA and the GCHQ. Surrounded by the darkness of the ocean’s depths, these worn cables are clinically documented by Paglen. In doing so, the artist reminds us that the infrastructure of a networked society relies on physical connection. These underwater cables serve as the factual antithesis of the myth of “the cloud.” Instead of looking up into the air—imagining our data as a light breeze that we can plug into at any given moment—Paglen looks deep underwater, where our data is encased in an engineered intrusion on marine life.

Photographing these cables in their “natural environment” reveals how the myth of contemporary network technology ignores the implications of their physical imposition. In Mythologies, Barthes argues that language is a fundamental aspect of building the mythology of oppressive regimes. For Paglen, the language of naturalizing myths (to continue to borrow a phrase from Barthes) is further complicated when it is used as a cypher. In his video installation Code Names of the Surveillance State (2015), a daunting list of phrases like “Broad Oak” or “Toxic Snow” slowly scroll vertically. The names, abstracted from their origin, present a freighting compellation of secret military operations.

Trevor Paglen. Installation view, Metro Pictures, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.

The stark white text on black background in this installation not only suggests a kind of clinical representation of declassified information, but it also reflects a certain kind of “gaze” that Paglen has slowly perfected. The “looking deeply” into the abyss has been a motif commonly found within earlier photographic works by the artist. Raven 2 in Corona Borealis (Signals Intelligence Satellite; USA 200), (2015) employs almost the same technique, though in this instance the artists peers into the cosmos to track the passing of a surveillance satellite. Where cables are shrouded underwater, a satellite is cloaked in celestial camouflage. In a striking gesture of aesthetic prowess, Paglen shows us two examples of technology attempting to blend in with their environments. In both images, however, these technologies are revealed to be as anything but natural.

Trevor Paglen. Installation view, Metro Pictures, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.

Paglen’s investigatory gaze continues to roam across the natural and into the built world of cities within a two-channel video projection Eighty Nine Landscapes. Similar to earlier photographic works in a series titled Limit Telephotography, this work captures locations that, according to the artist, “cannot be seen with the unaided eye.” Acting as one part voyeur and one part surveyor, Eighty Nine Landscapes traverses an array of locations. Shifting from urban sunsets, to military information gathering campuses, Paglen’s video and audio installation is simultaneously sublime and unnerving.

This duality—a pairing of visual elegance with political secrecy—could be considered the core of Paglen’s oeuvre. Where some works make that collision an unsettling experience others just as easily feel serene. It could be that Paglen is not trying to demystify the apparatuses of state-sponsored surveillance, but rather document how these technologies have become so naturalized within our contemporary landscape. One would suspect, however, that in performing the latter task, the former is soon to follow.

Trevor Paglen. “Autonomy Cube,” 2015. plexi box with computer components, 14 x 14 x 14 inches, 35.6 x 35.6 x 35.6 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.