Jay DeFeo: Alter Ego

September 12 – October 10, 2015

Hosfelt Gallery

260 Utah Street, San Francisco, CA 94103

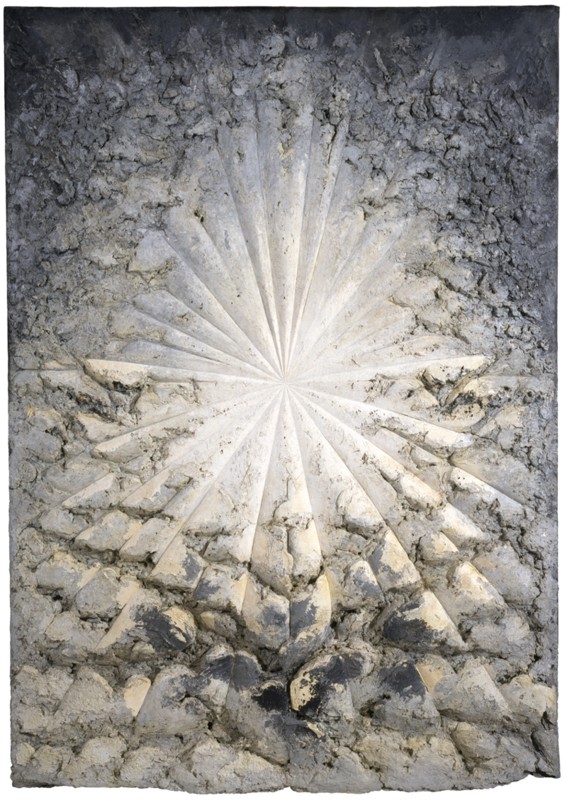

Bruce Conner’s film The White Rose (1967) documents the removal of his friend Jay DeFeo’s almost one-ton painting, “The Rose,” from her Fillmore Street apartment after a rent increase forced her from her home of many years. Conner’s black-and-white film embodies many of the qualities of DeFeo’s work: poetic, dark, beautiful, fierce, dedicated, meditative, and surreal. That “an idea that had a center to it” (as she described the urge behind her piece) became a monumental painting of a delicate flower, hundreds of paintings layered into the final piece that required cutting away part of the front of the building and a forklift to remove it, is poetic and gloriously absurd. “The Rose” was stored behind a wall in a conference room of the San Francisco Art Institute for twenty-five years until The Whitney Museum of American Art bought it in 1995.

Jay DeFeo. “The Rose,” 1958–66. Oil with wood and mica on canvas, 128 7/8 × 92 1/4 × 11 in. (327.3 × 234.3 × 27.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of the Estate of Jay DeFeo and purchase with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee and the Judith Rothschild Foundation 95.170

© 2009 The Jay DeFeo Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Aligned with the Beats, and fueled by freewheeling West Coast Zen/Pop sensibilities, DeFeo (1929-1989) has had two major retrospectives, one at The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2012, and at the Whitney Museum in 2013. Alter Ego, at Hosfelt Gallery, presents 55 of DeFeo’s paintings, photographs, collages, and drawings starting from the ‘70s, 46 of which are being shown for the first time. The exhibition is a discreet mix of DeFeo’s own sets of images and those of curator Todd Hosfelt. Its title, from the psychological and literary concept of “the other I,” of an intimate, constant friend that may be another side of our self or someone else, is a canny take on how DeFeo worked in small series that elaborated opposed-yet-bonded themes: figurative and abstract, right and left, photography and drawing, life and death, light and shadow, organic and artificial, monumental and intimate, personal and mythic, and male and female. It is even rumored that she may have changed her name to Jay to skew the notion of fixed gender.

Jay DeFeo. “Untitled,” 1972.

Gelatin silver print. 4 3/8 x 6 1/2 inches, 14 3/4 x 15 3/4 inches framed. © 2015 The Jay DeFeo Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Alter Ego features intimate black-and-white photographs of logs, hands, potted plants, rocks, leaves, clouds, mountains, and DeFeo’s dental bridge facing different directions or mirrored in reversed images. In 1970, DeFeo branched out into photography, creating small, dark, black-and-white gelatin prints. She developed her work by means of multiples; an installation shot in her studio inspired abstract drawings of some of its elements; a cut-out photocopy of a cloth or folded paper pasted on black paper lead to several abstract drawings that are flipped over or changed from black to white; studio tools, compasses, and tripods are drawn, photographed, or placed on top of a drawing and then photocopied. The two large gestural paintings, Hawk Moon No. 1 and Hawk Moon No. 2 (1983-1985), seem to be the result of her later poetic visual investigations.

Jay DeFeo. “Hawk Moon No. 1,” 1983-85. Oil on canvas. 84 x 60 inches. © 2015 The Jay DeFeo Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

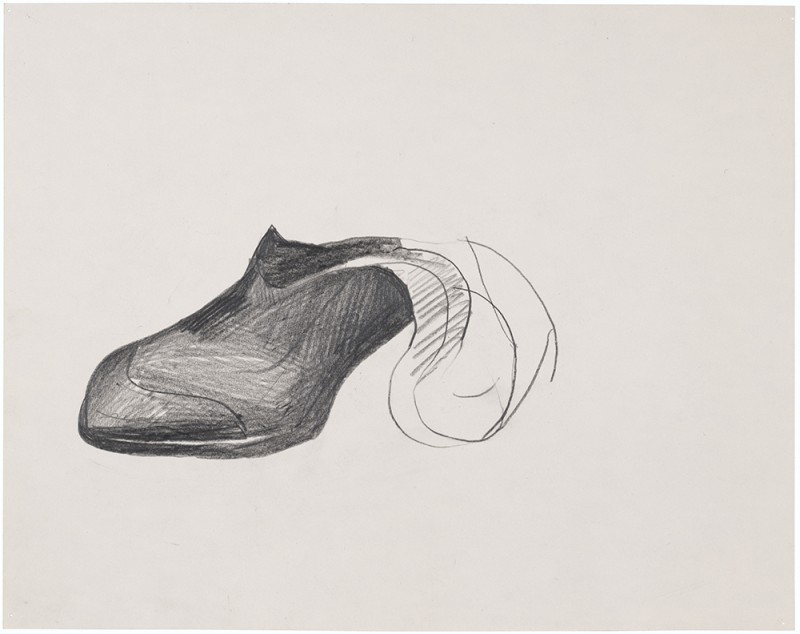

Seven Dwarfs (1989), a series of drawings, show a woman’s sandal, probably DeFeo’s, the straps twisted into different positions and named after the seven dwarfs in Disney’s Snow White. In the fairy tale, Snow White goes into a deep sleep after eating a poison apple and is guarded by the dwarfs until she is awakened by the kiss of her true love, all the while drifting between waking and dreaming, and conscious and unconscious. DeFeo was diagnosed in 1988 with cancer and would die a year later—perhaps Snow White is an alter ego, and the names of the shoe drawings are humorous signposts that point to her own suspension between life and death.

Jay DeFeo. “Seven Dwarfs: Bashful,” 1989. Graphite on paper. 8 9/16 x 10

7/8 inches, 17 x 18 3/4 inches framed. © 2015 The Jay DeFeo Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In Jean Cocteau’s famous surrealist film The Blood of a Poet (1930), a living statue instructs the artist to pass through a mirror. He obeys, finds himself in a hotel and, peering through various keyholes, spies an opium smoker and a hermaphrodite. A gun appears in his hand, a voice tells him to kill himself, and the poet shoots himself in the head. But he miraculously survives. He returns through the mirror and smashes the statue. In a 1946 essay on his film, Jean Cocteau wrote: . . .

The Blood of a Poet draws nothing from either dreams or symbols. As far as the former are concerned, it initiates their mechanism, and by letting the mind relax, as in sleep, it lets memories entwine, move and express themselves freely. As for the latter, it rejects them, and substitutes acts, or allegories of these acts, that the spectator can make symbols of if he wishes.(1)

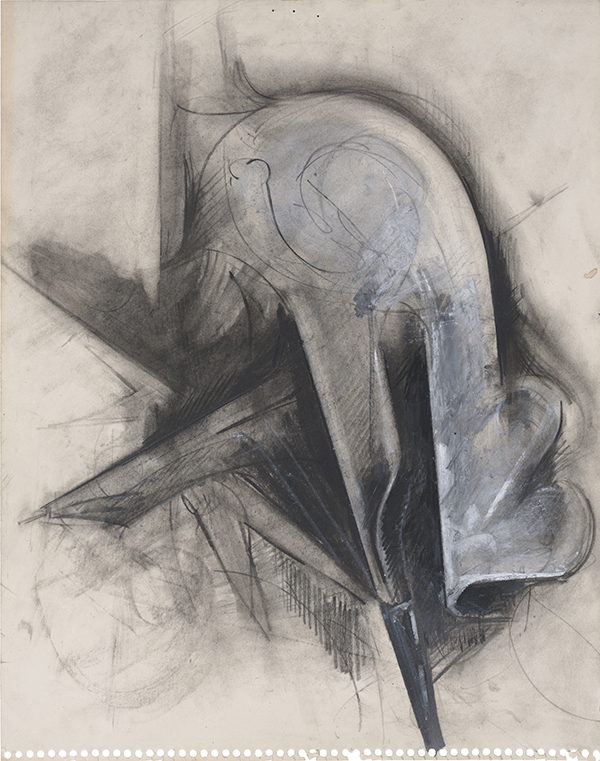

Jay DeFeo. “Untitled (Compass series),” 1979.

Charcoal and oil pastel on paper. 14 x 11 inches, 20 3/4 x 20 1/4 inches framed. © 2015 The Jay DeFeo Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

DeFeo’s metaphysical but concrete art functions in much the same way: the act of mirroring, or flipping images over and around, of changing black to white, of cutting through the surface of something, of changing liquid to solid, of waking and sleeping, of returning a different person to the place where you began your journey: such transformations are the very sensibilities of DeFeo’s art, not one of mere sentences but one of propositions, abstract, as direct as they are elusive, subtle, alive to indispensable distinctions.

Jay DeFeo. “Untitled,” 1972.

Gelatin silver print. 4 3/16 x 6 15/16 inches, 14 3/4 x 15 3/4 inches framed. © 2015 The Jay DeFeo Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.