Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo

June 26- September 27, 2015 (Michelangelo)

June 26 – August 23, 2015 (da Vinci)

Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes

Av. Juárez, Centro Histórico, 06050 Ciudad de México, D.F., Mexico

It may sound like a dusty snooze through Intro to Art History for anyone living in London, New York, or Paris, but Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo have come to Mexico City, and it’s a very big deal.

The blockbuster conjoined-twin exhibitions have smashed museum attendance records in Mexico and the historical significance of bringing these two artists’ work to Latin America for the first time makes this a trophy event for Palacio de Bellas Artes, the nation’s most important cultural center.

Line in front of Bellas Artes. People would arrive as early as 6 am to begin to stand in line for 3 or more hours to buy tickets, thereby forcing the Museum to contract Ticketmaster to handle the demand. Photo credit: Kimberlee Córdova

These exhibits are a grand coup of international cultural diplomacy and logistics, supporting the claim that, at least for the arts, this is the “Mexican Moment”. Though the works on display are comparatively “travel-friendly” compared to Michelangelo’s David or da Vinci’s Last Supper, exhibitions of this scale represent no small feat of coordination. Imagine the insurance, and conservation alone for irreplaceable and spectacularly fragile 500-year-old works on paper. Not to mention the complexities of shipping the five-foot tall marble Cristo Portacroce… yet, as a researcher for the exhibition explained, it only took a year and a half to organize!

There is a palpable aura to the objects touched by these artists. I say objects because I am not sure what to call them. How else should we refer to partially finished sculptures, abandoned by the artist and extensively reworked well after his death? Are preparatory sketches and anatomical studies art-with-a-capital-a? What if they might have been studies for the ceiling of the Sistine chapel? And what does it mean to display a copy of the Pietà? What if it’s the only copy in the world made of marble on a 1:1 scale? Do any of these questions matter or does it all just fall under the umbrella of cultural heritage?

Cristo Portacroche (1515) Michelangelo Buonarroti

Noticeable in this photo is the black vein that appeared in the marble ruining the face of the Christ sculpture causing Michelangelo to abandon it. The sculpture was rediscovered in 2000 at which point it was discovered that it had been heavily reworked in the 17th century. Photo credit: Kimberlee Córdova

The exhibition does not feature one single finished piece by Michelangelo. Both sculptures on display were abandoned, and the drawings are all prep studies with no proof of their association with the Sistine Chapel. Interesting as it is to see Michelangelo’s shopping list (also on display), given the dubious quality of the work in the exhibit, it’s obvious that what is thrilling about these circus-stunts of cultural diplomacy “exhibitions” is not the treasured bits of Renaissance studio flotsam that have been trotted out and set on display like gleaming jewels.

David-Apollo (1532), Michealangelo Buonarroti

There remain multiple questions about this unfinished sculpture of a boy. It is unknown why Michelangelo left it unfinished as well as who it is supposed to depict. Some theories suggest it is a young version of the David, while others suggest perhaps it is supposed to be an Apollo. Photo credit: Kimberlee Córdova

So we are left asking why? Why are these works being displayed in Mexico’s most important cultural center today? And what kind of message does it send to the public to allocate this quantity of the ever-dwindling cultural budget to the exhibition of works of such marginal quality with minimal educational museographical elements? How do they fit into the curatorial mission of the museum? (For the record, these exhibits do fit into the curatorial mission but only because, according to a former staff member, there isn’t one.)

The fact is that these exhibits are not exposing the general public to heretofore uncelebrated talent. It’s tough to think of a pair of artists more canonized. Nor is this collection of their work particularly relevant to life today other than to “detail the spirituality and physicality of man and give dimension to the plenitude of humanism.”[1] Whatever that means. These exhibitions are mounted for the purpose of cultural-political absolution by association with a celebrated past; a sort of reverse exoticism of old European culture is at work here upholding a colonialist value system.

Rafael Jimeno. “View of the Plaza of Mexico, newly adored with the equestrian statue of our beloved reigning King Carlos IV.” 1797. Etching on paper. Museo de la Ciudad de Mexico, Distrito Federal Mexico. Photo credit: Kimberlee Córdova

Because of their operational structure, to talk about museums in Mexico is to invoke a conversation of political critique if only by following the money. The exhibition programming in general at Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes feels archaic because its operating structure does not afford it the chance to be otherwise. Managed on 6-year cycles, institutional leadership is cleaned out and reinstalled one presidential administration to the next, leaving no time to develop an exhibition program with an overarching vision, supported by rigorous scholarship and sustained by reliable financial support. Additionally, year-to-year budgets are cut and swapped around with no recourse or transparency, thereby making exhibition planning difficult for museum staff. Granted, budget cuts, leadership challenges, and questions of cultural value are problems in the cultural sector everywhere. But in Mexico the trade-off to government funding is that museums have no fiscal autonomy. They have no endowments; even their earned income from admissions is included as part of the funds they receive for the next year’s budget. Additionally, the collecting class is comparatively small, and public-private partnerships are relatively unheard of. The result is that there is no alternative system to turn to should the state fail to meet the museum’s operating needs.

And what of the argument that these exhibitions offer people in Mexico, who would never have the opportunity to travel to Italy, the chance to see—in the flesh, so to speak—these works so precious to humankind?

Antique table depicting the Sistine Chapel. Photo credit: Kimberlee Córdova

If the purpose of the exhibition is to bring this work to an audience with little exposure to the arts, then where are the didactics and educational elements that explain these works and put them in clear relationship with one another and their influence on “New Spain”? Why, if the museum is trying to communicate grandeur by showing the 9 sketches on display that may have been studies for the Sistine Chapel, are they using a small antique card table with an image of the chapel’s ceiling as the only reference to the famous fresco? And why is it displayed alone inside a bizarre little box-cave?

The exhibition is oddly laid out and strangely curated. The attempts to tie the works to Mexican history, as referred to in the few didactics, seem perhaps well intentioned, but so poorly executed it’s hard to say. What is clear is that a superficially newsworthy exhibit-spectacle was slap-dashed together so that this administration (of the museum or otherwise) could say Mexico was the first to bring these Renaissance masters to Latin America.

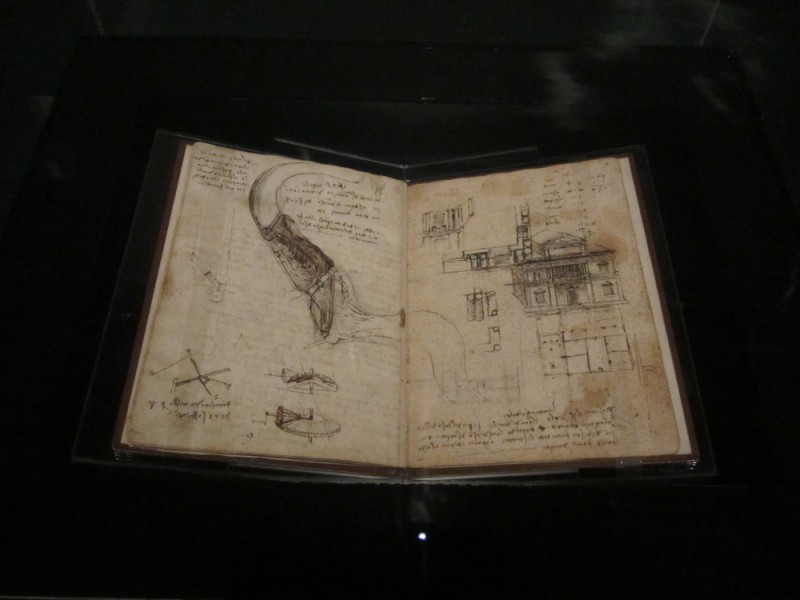

Leonardo da Vinci. “Codex on the Flight of Birds,” 1452-1519, sepia ink and sanguine on paper.

Biblioteca Real, Turin, Italy. Photo Credit: Kimberlee Córdova

As for da Vinci’s exhibition, La idea de la belleza—curated by Dr. John T Spike and previously exhibited in Boston, Massachusetts and Williamsburg, Virginia—the highlight is undoubtedly the Codex of Flight, even if the moment of seeing the single spread scribbled by the Renaissance man’s own fingers is an anticlimactic notebook of ingenious yet indecipherable (to the lay person) early engineering and personal budgets. With no museum explanations and no images of the other pages on display, visitors are on their own to look up whatever gems of ingenious human history the rest of the book holds… or buy the catalog.

Standing there, staring at the age-spotted ochre pages, imagining the work and resources it must have taken to bring it here, a mind wanders to other equally suspicious “flights” in Mexico with exorbitant prices the public must pay: Mexico’s presidential plane, the most expensive presidential aircraft in the world; or the second flight of El Chapo, which occurred during the run of the exhibition; the helicopter shot down by narcos with rocket propelled grenades in May; and faith in Mexico’s leadership in general which has long since soared away.[2]

Perhaps it’s cynicism, a distancing reaction to the July 31st murders of Ruben Espinoza and Nadia Vera along with three other women that have shaken the country and shamed its leadership, but when walking out of the museum, yet another protest was marching by, making it hard to imagine which “idea of beauty” el Palacio de Bellas Artes could be referring to by bringing these works to Mexico—other than the macabre beauty of dictatorship perfected, an insidiously sublime harmony of parts, which undoubtedly includes arts and culture.

—

[1] https://twitter.com/rtovarydeteresa Rafael Tovar y de Teresa, Presidente de Conaculta, Aug 2 2015

[2] The transport and insurance of the works had an estimated cost of 17 million pesos, in today’s dollars that is $105,1742.74 http://www.excelsior.com.mx/expresiones/2015/06/27/1031561