Petra Cortright: NIKI, LUCY, LOLA, VIOLA

July 9 – September 12, 2015

Depart Foundation

9105 Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90069

The Internet is for porn. The worldwide web’s precursor, ARPANET, was created by U.S. Department of Defense scientists in 1969 as a communication network in the event of nuclear war—but the network’s development into an advanced system of information exchange really began with users’ attempts to share nudie pics while evading government censors. As the hunger for simulated flesh grew, early ASCII porn—erotic images drawn with computer typography—became thumbnail photographs, requiring higher bandwidths and better graphics processors. Sexual fantasy has always been an engine of technological innovation, and the Internet opened infinite depths of desire to plumb.

Petra Cortright’s exhibition at Depart Foundation in West Hollywood fits somewhere along this historical continuum of robotic erotics. In NIKI, LUCY, LOLA, VIOLA, virtual strippers that Cortright purchased on VirtuaGirl.com dance against a green screen and two animated desktop backgrounds. What’s first striking about the women is their photorealism. They appear real because they are: VirtuaGirl films and records live models acting out specific motions in front of a green screen, creating recombinatory sets of seductive dance moves that can be customized and replayed endlessly by paying clients. It’s basic software that’s been around since 1998, but recent upgrades allow users to customize the strippers’ features too, from varying skin tones and hair colors to the height of their heels or the amount of fringe on their skimpy Santa Claus costumes. The next logical step, one can imagine, are the intelligent “teledildonics” of Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie, or yet-to-be-programmed orgies enjoyed via Oculus Rift.

Petra Cortright. Installation view, “Niki, Lucy, Lola, Viola,” 2015. Courtesy of Lyn Winter. Photo: Jeff McLane

Cortright downloaded the strippers using a prepaid Discover card to avoid catching viruses. Each one is dressed in “sexy” apparel—pink thong and white pasties, a latex nurse uniform, black garters and a leather eye mask. They came with their own names, which appear in the show’s title. In the exhibition’s largest work, the four named females and several digitally altered clones twirl around poles anchored in the screen’s lower edge, or crawl with arched backs, staring straight at the viewer. They lustfully return our gaze, yet with eyes vacant of subjective agency—tirelessly performing the same movements that grow stale with each recurrence. In addition to this work, Niki, Lucy, Lola, and Viola also appear on green flags that hang above the gallery entrance, waving at Sunset Boulevard like derby girls at a testosterone-fueled Nascar race. The seeping scent of cigar smoke from the tobacconist next door is a happy accident, a bit of sensory sleaze that heightens the strip show’s fleshy realism.

Cortright is one of Internet art’s hottest tickets. Her speechless yet intimate YouTube videos meditate on the way images are circulated and manipulated in our self-involved selfie era. In these videos, readily available online, Cortright uses subtle digital editing to distort her own image, recorded by a laptop camera and reflected on a screen. In snow1??? (2011), for instance, white pixels drift across the video’s glitchy frames, settling on Cortright’s shoulders and hair, looking a lot like fresh snow and a little like dandruff. In sick hands (2011), a wave courses through the frame, rendering her body like an undulating Edvard Munch figure. In each work, Cortright confronts the camera and the viewer, always seemingly on the verge of a verbal address, recalling the millions of home movies uploaded by YouTube users speaking to anonymous listeners—public confessions that usually fall on deaf ears. “YouTube celebrities,” whose popular videos have led to TV shows and book deals, make the rest of this confessional traffic seem frivolous and self-important by comparison. Cortright’s work appears to comment on this condition of public anonymity intensely heightened by social media, and our perpetual hankering for likes, shares, and retweets. Seen through her online work, she’s a cyberpunk pixie who embodies the meme generation’s stale disaffection with a shrug.

Petra Cortright. Installation view, “Niki, Lucy, Lola, Viola,” 2015. Courtesy of Lyn Winter. Photo: Jeff McLane

In the vein of her videos, Cortright’s projections at Depart cycle like endlessly repeating GIFs, their animated movements progressively predictable. Their motions are familiar to anyone who has ever visited a strip club—a quick yet seamless succession of breast-pumping hand gestures and booty-bumping squats. Bean bag chairs strewn about the dark vaulted space invite a studied viewing, but it doesn’t take long to realize that those repetitious gestures are all that’s there to see. Could there be a hidden message, one wonders, in a projection of a digi-stripper being dragged upward by an invisible computer mouse and dropped in a sky-blue expanse filled with seagulls, her miniskirt billowing in the wind? These are not carrion birds, and the stripper seems to feel no pain or pleasure in the act (unless they’ve taught computers how to do that too).

In a third projected video, a stripper dances teasingly on the mottled earth of a desert expanse, an animated flame burning eternally on its pale white horizon. Beside her, an elephant walks hopelessly in its tracks, and a horse tosses its head side to side—a literal one-trick pony, trying to satisfy a desperate itch. A generous reader might regard the woman here as debased, like an animal, by male sexual objectification, groomed for saddle or slaughter. But the aesthetic of Kid Pix 3D has dropped each figure into a visual wasteland too conceptually starved for striking associations to bloom. This is in marked contrast to Cortright’s first stripper video, Vicky Deep in Spring Valley, which premiered in Berlin in 2012. In it, a stripper dances around a pole atop an outdoor architectural folly: an Egyptian colonnade that is at once an aquarium, an aqueduct, and a jungle garden pavilion, housing black swans and tropical fish. Amplified to absurdity, each artistic element serves only to please the viewer, its substance subservient to their gaze. Cortright’s self-conscious embrace of digital fantasy makes her ironic detachment from such scopophilia all the more apparent.

Petra Cortright. Installation view, “Niki, Lucy, Lola, Viola,” 2015. Courtesy of Lyn Winter. Photo: Jeff McLane

Cortright’s latest work makes no claim to gender politics, though such motivations have been ascribed to it. She does seem to examine biopolitics in the digital age—at least how we turn on to get off. But interpreting this strip show as an act of feminist subterfuge would rely too much on the artist’s presumed sexual and gender identity. Art must use the aesthetic and institutional tools at its disposal to render such politics legible to a viewing public, or else fail to move even its staunchest ideological bedfellows.

In itself, VirtuaGirl is an appealing subject for feminist annotation. E-commerce and phallocentrism collide online, commodifying the female body so extremely that male sexual desire often takes not flesh but pixels as its object. The Internet makes no excuses for its Rule 34 diversity—a dizzying wormhole of perverse fantasy where two girls and one cup mean a lot more than a shabby cocktail party. Often the IRL bodies exploited by this web-streamed system disappear in service of male pleasure. But they’re no more visible at Depart Foundation, where even the exhibition didactic fails to mention the live videos of live girls VirtuaGirl uses to produce its simulated Build-an-Escort factory. Indulging in this roulette wheel of erotic selections might be the first step towards a fruitful critique of male chauvinism—but it is certainly not its last. Cortright’s politics stop cold at consumption, missing the chance to make a truly meaningful statement, leaving the viewer with conceptual blue balls.

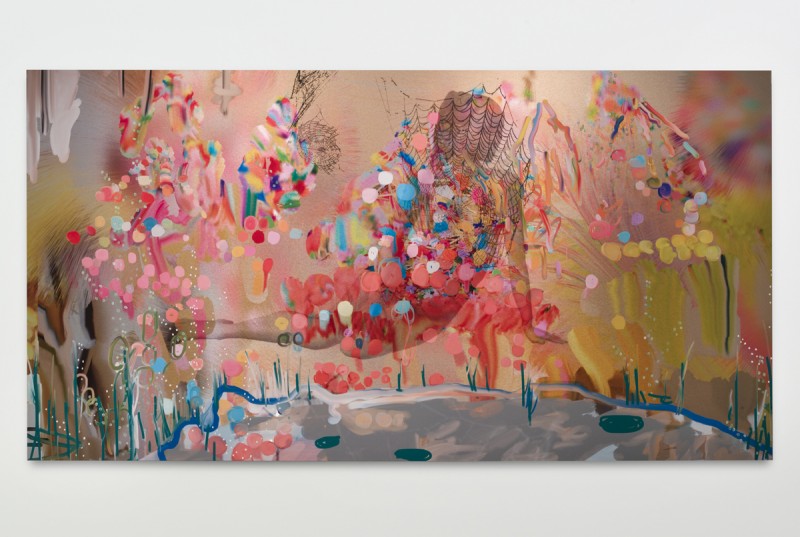

Petra Cortright. “Brunettefat chicksfat chicks nudefat,” 2014.

Digital painting on aluminum.48 in x 91.5 in. Courtesy Lyn Winter. Photo jeff McLane

The exhibition’s hype is predicated in part on the spurious presumption that “new media” means new ideas. There is nothing more sycophantic or sexualized about Cortright’s girls than the frivolous females in a Fragonard or Boucher painting. They are no more or less vulgar than de Kooning’s lascivious women. They are, part and parcel, the inscription of male fantasy, carved violently by hands invisible within the project’s frame. Is there agency in such outlandish debasement? If so, who does it belong to—“real women” or computerized figments?

Maybe Cortright isn’t interested in these questions, or maybe she’s just having fun. It’s not the critic’s job to spoil good fun, but to give credit where it’s due. Cortright puts on a good show, one more at home on a Fantasy sports league website banner than in an art gallery—two disparate platforms whose collapse is surely a welcome (if slightly unexpected) exercise. But, conceptually, the work performs little more than a regurgitated fantasy. It makes the strange not a bit stranger, rendering a space for us to enjoy our guilty indulgences even at the expense of others. The Internet is for porn; and that’s all there is to it. Now go grab your Kleenex.