Fermín Jiménez Landa: El Nadador

May 2 – August 2, 2015

MAZ: El Museo de Arte Zapopan

20 de Noviembre, Zapopan, 45100 Zapopan, Jal., Mexico

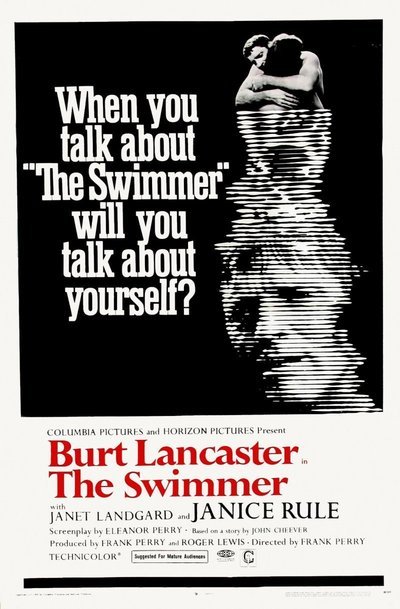

The movie poster for the 1968 Burt Lancaster film The Swimmer features a portrait of the star’s face dissolving into a swimming pool wake, and asks in that Vaseline-around-the-edges-soft-focus-dated-movie-poster-way, “When you talk about ‘The Swimmer’ will you talk about yourself?”

Film Poster. “The Swimmer,” 1968.

Drawing inspiration from the film, artist Fermín Jiménez Landa’s exhibition at El Museo de Arte Zapopan (MAZ) of the same name, El Nadador—The Swimmer, appropriates the film’s use of swimming pools as social vignettes to explore themes of private space, vulnerability, and the value of “wasting time”. In the film, we discover that Ned Merrill, the title swimmer, has some kind of self-imposed-amnesia and is unable to recall the last two years of his life. Willfully clueless and naturally vapid, he has no voice of his own outside expressing his desire to swim (and drink) his way home, pool by pool, relying on the hospitality of friends. Like an affable mashup between Ryan Lochte and Patrick Bateman on Xanax, he crashes party after party—his anecdotal interactions revealing the social dynamics of the late 1960s upper-class as well as clues about his forgotten identity.

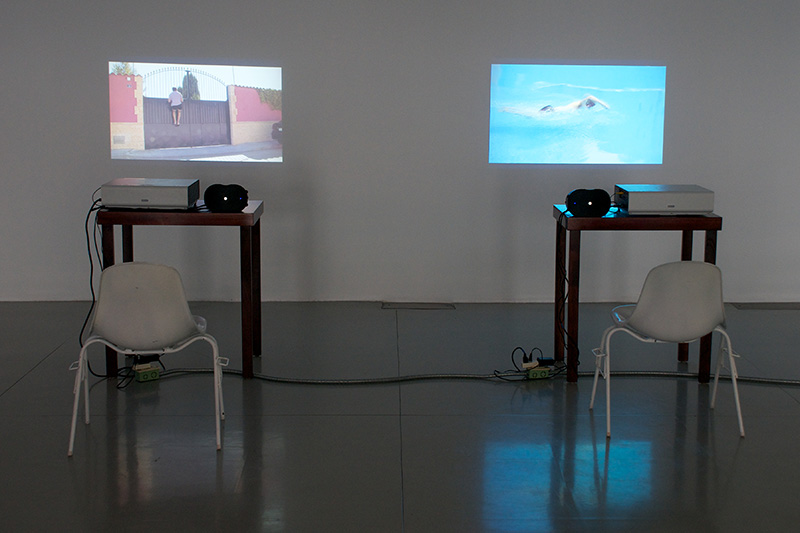

Fermín Jiménez Landa. “The Swimmer (Guadalajara),” 2013. Video. 8’54’’. Courtesy of the artist and Galería Bacelos. Photo credit: Maj Lindstrom

In El Nadador, Jiménez Landa appropriates Merrill’s aquatic-navigation methodology. Like a swim-nut motivated by real estate voyeurism, he appears unannounced at private homes with swimming pools in Spain and Guadalajara. First performed in 2013, he drew a straight line across Spain by swimming in pools from Tarifa to his parents’ home in Pamplona using Google Earth to identify his targets. Invited by MAZ to recreate the performance across Guadalajara, El Nadador furthers Jiménez Landa’s investigation by presenting side-by-side videos of his prying performances in Spain and Mexico.

Fermín Jiménez Landa. “Towel,” 2013

Towel. 90 x 140 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galería Bacelos. Photo credit: Maj Lindstrom

While walking through the exhibition there is a distinct impression that this is more a room full of artistic exercises related to the performances rather than a display of thematically related self-contained art objects. This curatorial election to exhibit exercise-like works that reinforce central concepts of the performances, keeps the mood light while maintaining the exhibition’s focus on the interactions between the artist and pool owners rather than the documentation thereof. Set on the floor with the toes pressed against a blank white wall, the artist’s swim sandals from the performances open the exhibit, suggesting the swimmer’s presence requesting permission to enter and tempting the viewer to imagine standing at a foreign door begging a stranger for a quick dip.

Fermín Jiménez Landa. “The Swimmer, visual essay,” 2013. Digital prints, Variable dimensiones (31 elements). Courtesy of the artist and Galería Bacelos. Photo credit: Maj Lindstrom

To the left, a curved aqua-colored wall—perhaps an allusion to the proclivity for kidney bean shaped pools—displays a collection of found images of pools from around the world. From the world’s largest pool that was constructed on the repurposed site of a cathedral in Soviet-era Russia, to boozy motel pools in swinging mid-century Palm Springs, Jiménez Landa provides a comprehensive catalog of swimming pools as philosophical constructions built to facilitate different desired social interactions; they are reflections of their socioeconomic and sociopolitical contexts.

Fermín Jiménez Landa. “Sicily,” 2013. Sicily model swimming pools, 85 x 45 x 40 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galería Bacelos. Photo credit: Maj Lindstrom

Opposite the collection of appropriated historical pool images is a lineup of identical miniature polyester swimming pools, standing smartly at attention. Devoid of water and calling to mind prefab tract housing developments for drought-stricken suburban Barbie dolls, the pools couldn’t negate pool-ness more. Not only are they empty, they are standing. Are they denying the opportunity for recreation like some kind of refusal of the hallmark of summer? Or are they meant to call to mind a glittering bird’s-eye view of Jiménez Landa’s target pools, winking seductively with possibility if stripped of originality? In either reading, their commoditized seriality seems to underscore a surreal sense of existential doldrums…a classist prefab invocation of the summertime blues.

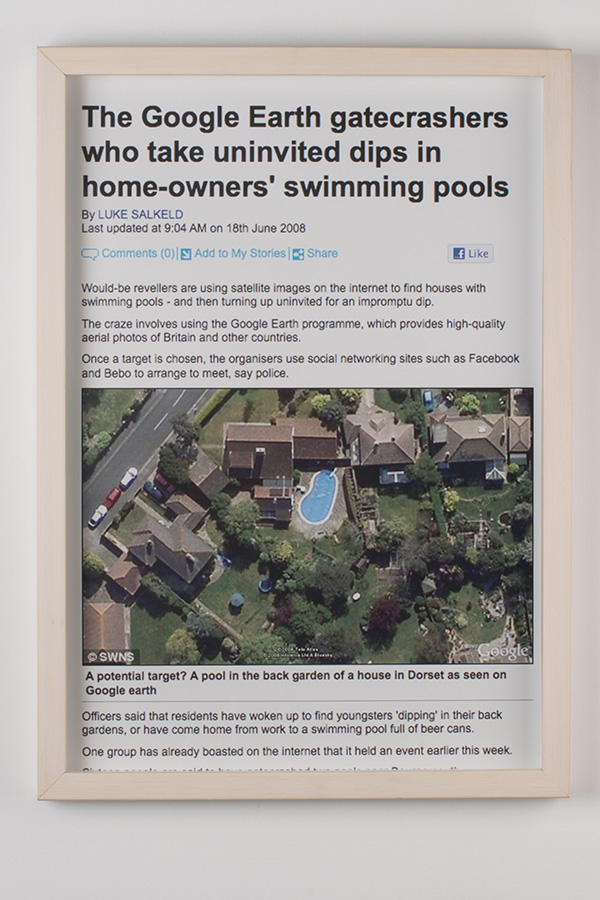

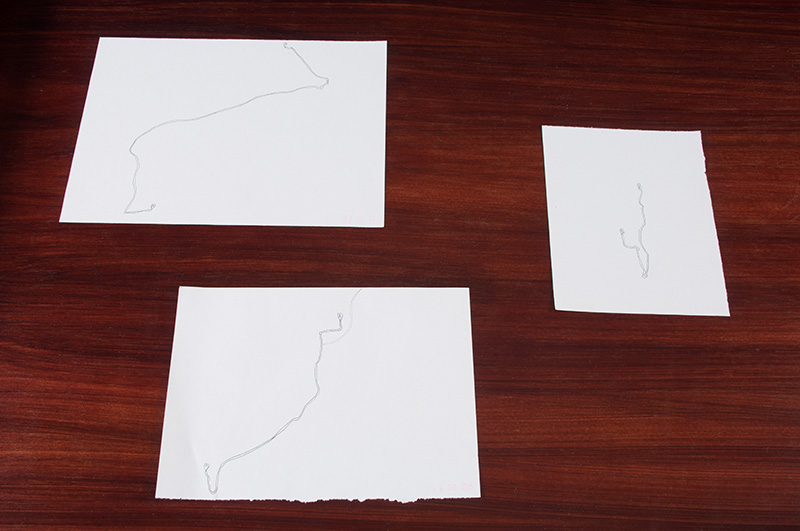

Other pieces in the room include the artist’s towel, pencil copies of Google maps that suggest drawing as product of the intersection between digital surveillance, performance and documentation, and a poster-sized print of a Daily Mail article about British party kids using Google Earth to target homes to throw pool parties while the families are away.

Fermín Jiménez Landa. “Uninvited Dips,” 2013. Digital print. 35 x 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galería Bacelos. Photo credit: Maj Lindstrom

Both Merrill and Jiménez Landa force confrontations with social structures vis-à-vis private property and the physical construction thereof, but where Merrill employs his social cadre and hometown familiarity to chart a course through private yards dependent on favors of privilege, Jiménez Landa exploits 21st century slippages in notions of privacy through his reliance on Google satellite imagery. With El Nadador he suggests the need to reconsider the distinction between private and public space in light of digital surveillance, using his unexpected presence and physical vulnerability to nature and potentially hostile strangers as an opportunity for insight.

Fermín Jiménez Landa. “Routes from A to B,” 2015. Pencil drawings on paper. Variable dimensions (18 elements). Courtesy of the artist and Galería Bacelos. Photo credit: Maj Lindstrom

A sharply noticeable difference between the two performances/videos is the comparatively unaffected warmth of reception by the pool owners toward the artist in Spain versus the suspicion and anxiety he confronted in Guadalajara. In Spain, the artist usually encountered bemused, if befuddled, pool owners who were willing to just “go with it” or fences so low and casual that they seemed incidental. In Mexico, Jiménez Landa found fortress-like properties with high walls, threatening dogs, and elaborate security systems with guards and intercoms meant to give owners’ a feeling of military-grade protection. Reflecting an overall sense of fear resulting from Mexico’s general lack of public security and a flair for telenovela drama, one woman told him through her intercom, “It’s best if you forget this place and never come back.” The irony being that even the highest walls and most vigilant guards are useless against the threats posed by Internet technology and contemporary surveillance.

Installation view. “Fermín Jiménez Landa: El Nadador (The Swimmer),” MAZ: El Museo de Arte Zapopan. May 2 – August 2, 2015. Photo credit: Maj Lindstrom

In the film, Ned Merrill arrives at his home to find it boarded up and empty. In Spain, Jiménez Landa arrives at his parent’s home, where we assume he was comfortably and warmly received. In Mexico, he arrives at the site of the last pool to discover it has been filled in, fenced off, and guarded by a barking dog. The movie poster was prescient after all, for when we talk about El Nadador, we indeed must talk about ourselves.