San Francisco’s spring art fairs, which took place during the weekend of May 1-3, offered three disparate venues and a smorgasbord of artists to meet and art to view and consider for purchase. For those attracted to a classic art fair, with well-appointed booths staffed by gallerists, featuring artists they represent, Art Market was the destination of choice. By contrast, the Start Up Art Fair, held at the Hotel del Sol several blocks from the Fort Mason location of Art Market, provided a more intimate experience. Visitors could stroll through guest rooms that were temporarily converted to unique exhibition spaces, designed and managed by artists. The stated intention of this “independent art fair” was to afford artists who do not have gallery representation an opportunity to personally show and market their art to potential collectors. Far the more unorthodox, the Parking Lot Art Fair, held for five hours in a lot adjacent to Fort Mason (a location announced the morning-of via Facebook), was an intervention as much as it was an art fair. Among the attractions at this pop-up event were performances, interactive art projects, small vehicle-based mixed media exhibitions, and the opportunity to learn of and support the work of younger, emerging artists.

The experience of these three fairs brought to mind accounts of the Paris Salon and its counterpoints in the late 19th century. In analogous ways, the “official” fair was Art Market—the Salon—with its conventional structure. At that venue, galleries from the Bay Area and beyond rented spaces in which to show and sell the finest or most interesting work by their top artists. A heightened air of formality and importance was accorded to the featured art and artists in each booth. Knowledgeable gallerists were generally eager to talk with visitors, although in some cases sat aloof, as they might when in their own galleries. The latter circumstance seemed strange for participants in an art fair, but perhaps my experience was particular to the times during which I encountered their exhibits. There were also some wonderfully uplifting moments, among them my encounter with the lively gallerists that hosted The Dryansky Gallery booth on opening night.

Wanxin Zhang, “Return to the Garden of Eden,” 2011-13. High-fired clay with glaze. 80 x 30 x 38 in. Courtesy of Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

Wanxin Zhang, “Special Ambassador,” 2011. High-fired clay with glaze. 74 x 22 x 8 in. Courtesy of Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

Most significant, Art Market offered a lot of well conceived and executed art. Some standouts included Davy and Kristin McGuire’s whimsical holographic video sculpture from their Fairies series (Muriel Guépin Gallery); Chris Dorosz’s Stasis 97 (Riot), an intriguing series of figures painted on a sculptural installation of acrylic rods, structured so the grouping conveyed a sense of three-dimensionality and movement (Scott Richards Contemporary Art); Lalla Essaydi’s Les Femmes du Maroc: Harem Beauty #1, a large chromogenic print triptych of a recumbent “harem beauty” in a full-length gown, rendered exotic with ink inscribed text over the surface of the figure (Jenkins Johnson Gallery); and Lava Thomas’s Cloudscape Portrait 9401, a luminous laminated pigment print (Rena Bransten Projects). Chris Hedrick’s Hoodie on a Hook, a wonderful trompe l’oeil sweatshirt carved from Alaska yellow cedar (Axiom Contemporary); and Wanxin Zhang’s two poignant and monumental sculptural ceramic figures Return to the Garden of Eden and Special Ambassador, positioned sentry-like near the entrance to the fair, set the tone for this well-orchestrated event (Catharine Clark Gallery).

The Start Up Art Fair seemed homologous with the historic Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Refused), as it was created to showcase those artists who didn’t have gallery representation (although this situation was not entirely true). Artists were selected for this fair by jury and were allowed control of their installations. Artists’ presentations ranged from those that were relatively traditional to those that were quite playful. The overall tenor of this fair was more intimate, due to its venue and, most significantly, the opportunity to meet and talk with the artists while wandering through their rooms.

Chris Thorson, “Plastic bag—Nice Days (Thank You),” 2011-2014. Beeswax and natural dyes (grown by the artist) on organic silk. Courtesy of the artist.

One of the most unusual installations was created by Chris Thorson, whose room, at first glance, suggested that she had dropped clothing and objects—a sweater on one corner of her unmade bed, dirty socks on the floor, grape stems, keys, a TV remote control, a glove on the hotel room desk—and had thrown a plastic Lucky supermarket bag on the floor. Closer examination revealed these objects to all be faux reproductions, mostly created with hydrocal. It was fascinating to watch potential visitors peer into the room, and, unable to determine that the strewn clothing and objects were part of an art installation, walk quickly away. Perhaps the art/life merge veered too far on the life side for their tastes, or the intimacy it suggested made them uncomfortable. Nonetheless, it was enjoyable to witness visitors’ reactions when they chose to enter the room and discovered Thorson’s masterful counterfeiting.

Other memorable artists included Jennifer Yeuroukis, who used her bathroom as a performance space, partially filled with aromatic grapefruit and broken glass (in the sink) to heighten viewers’ sensory experience. Jennifer Kaufmann’s inventive mixed media works included a tape drawing that began on her room’s walls and extended off the wall and into space, creating a dynamic and site-responsive approach to the room’s architecture. Photographer Shane Gidcumb created a striking installation of large-scale images from his City Clouds series, which address how the cumulus and nimbus we are accustomed to seeing when looking skyward have been replaced by a matrix of geometric forms that house anonymous offices and workers—simultaneously striking and disturbing.

Jennifer Yeuroukis, recording of performance at Start Up Art Fair, 2015.

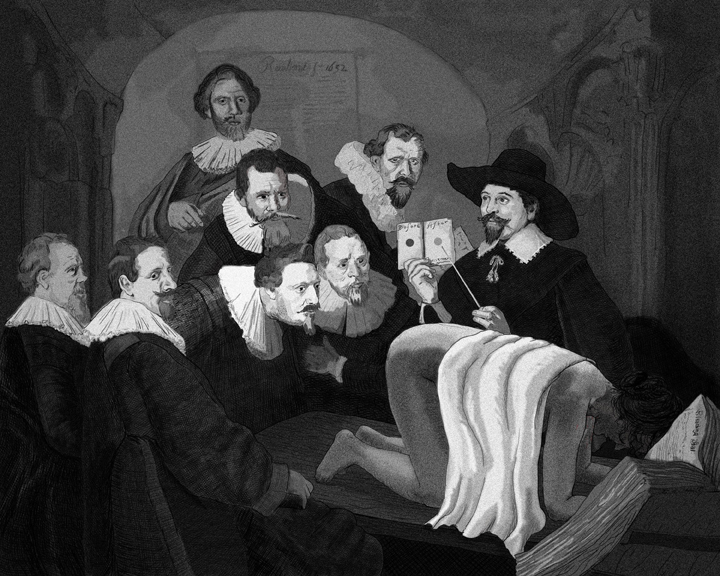

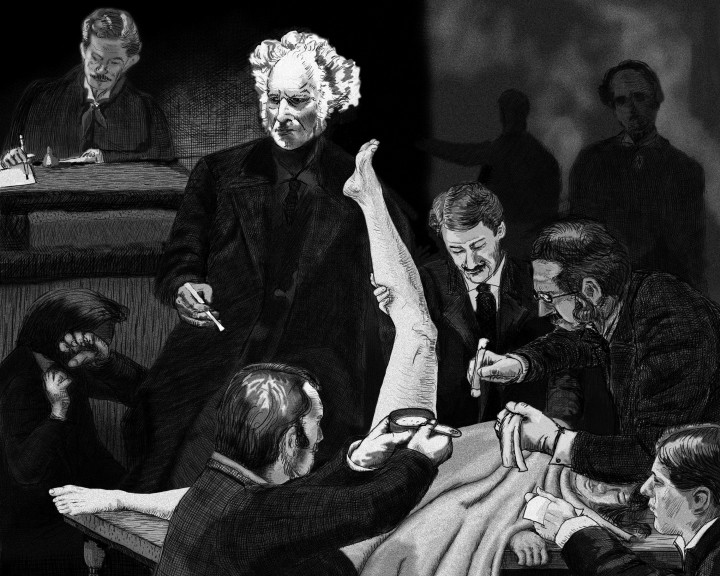

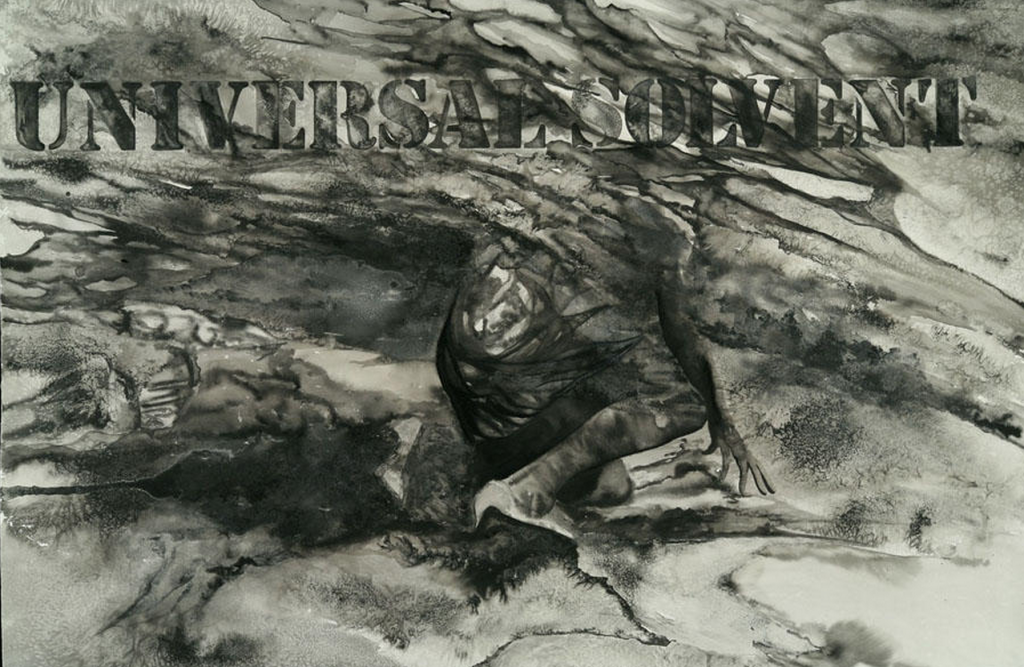

Among the many other artists whose work deserves mention were Kelli Scott Kelley’s personal and surreal paintings on repurposed antique linens. Kelley’s enchanting, sometimes disquieting fantasy images describe stories that reflect the artist’s Southern heritage, as well as her deep interest in fairy tales. Kathy Aoki’s Museum of Historical Makeovers, comprised of etchings that appropriate and deconstruct historical masterworks, comments on ideas central to contemporary beauty and pop culture. Aoki’s prints in this series, based on such paintings as Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic, and Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson, depict surgery scenes that Aoki humorously revised to become ironic versions of current beauty procedures, including The Brazilian and The Bleaching Lesson. Also interested in historical paintings as the basis for his art, photographer Bijan Yashar positions his camera at a low angle, relative to existing gallery lighting, while re-photographing paintings in various collections, so the resulting glare blots out key details such as subject’s faces. For his Illuminated/Eliminated series, Yashar created archival pigment prints of the resulting images, embracing the ongoing dialog between photography and painting. For me, the most moving works at this fair were Rodney Ewing’s three series of mixed media silkscreens and watercolors, which reveal his desire to challenge preconceived ideas about social issues and create dialogue. In his Rituals of Water series, in particular, Ewing addresses ways that water has affected the African American Diaspora, providing an important complement to the conceptual and narrative admixture of artists invited to participate in this fair.

Kathy Aoki, “The Bleaching Lesson,” 2009. Etching. 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Kathy Aoki, “The Brazilian,” 2009. Etching. 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of the artist.

The wild card in this weekend of creative expositions was the Parking Lot Art Fair, which one could also consider the “Salon des Refusés’ Refusés.” Although the artists participating in the Start Up Art Fair paid a fee to show their work, they were also afforded the opportunity to keep the return on all sales. Conversely, artists in the Parking Lot Art Fair lay out their work street-fair style, or did performances in their locations adjacent to Fort Mason, but were not “officially” selling their work. The brevity of the Parking Lot Art Fair was a disadvantage in terms of reaching a broader audience, but did result in heightening expectations and energy, as the participating artists wanted the most return for their efforts. Some used their vehicles as an exhibition space, and exhibits ranged from such creative projects as an installation of miniature sculptures in a makeshift suitcase (a sort of Duchmpian Boîte-en-valise) exhibited in a car and created by an artist named Kat, whose itinerant studio/living spaces are obtained via housesitting; to the Kunst Haul Collective, whose 11-artist show was staged in a U-Haul truck. Farley Gwazda’s Debt Hypercube, and Indira Moore’s Wallet Desire Card projects addressed concerns about money—especially issues of debt, ownership, and social mythologies about money. Gwazda created the “Art Collections Agency” (pun intended), which allowed the “purchaser” to take possession of one of his hypercubes for $1.00 for a period of one month, a debt agreed upon with a signed contract that would be cancelled upon the return of the object. One of the cleverest projects in this genre was an edition of 25 pancakes, created for public consumption by The Thing Quarterly, an object-based publication created by artists Jonn Herschend and Will Rogan. The limited production of this edition was predicated on the non-commercial rules of the fair’s particular location.

Rodney Ewing, from the “Rituals of Water” series. Ink, water, and salt on paper. 60 x 40 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Discussions with the various fair organizers were a significant means to gain insight into their structures and goals. Kelly Freeman, communications director of Art Market, discussed how this Brooklyn-based organization represents artists “in a highly curated way . . . we curate exhibitors, not artists or audiences.” Their central objective for this fair was partnership, which for Freeman centered on Art Market’s local and gallery collaborators, and helping people “encounter things in new ways.” This included an educational component—panel discussions on putting together exhibitions; a Robert Motherwell program; making the fair a “platform for education”; facilitating conversation with visitors; and providing docent tours through the exhibits. Similarly, Christine Duval, who was part of the advisory council for the Start Up Art Fair, explained that the fair’s educational incentive was to help artists market and sell their own work. Another primary hope and goal of the Start Up Art Fair was for artists to be offered representation by galleries (at least a few!), setting up a kind of tension between helping artists build a client base by selling their work directly to interested parties, yet also having the goal of obtaining a gallery to represent them. Start Up Art Fair’s organizers, artist Ray Beldner and gallerist Steve Zavattero, reiterated this goal. Yet, Beldner and Zavattero also shared their feeling that as the economy has changed, galleries have been closing, and much art world commerce has been moving to the Internet, that “this fair will be a success if even a handful of artists get gallery representation.” Somewhat more optimistic, Jenny Sharaf, founder and director of the Parking Lot Art Fair, also expressed a hope that artists “would meet their future collectors.”

Simon Pyle, “Screen of the Headlands,” 2015. Installation at the Parking Lot Art Fair. Courtesy of the artist.

Considering the economies of these three fairs is one of their most significant takeaways. In addition to showcasing art and artists in various ways, each fair’s planned activities—lectures, panels, parties, tours, food, fun—and structure were intended to enhance audience experience, support maximum attendance, and heighten sales. While each fair had a different philosophical stance and approach to sales, ultimately their shared goal was to promote visibility of their artists, educate the public about contemporary art, and encourage the public to become art supporters and collectors. How successful this was for each fair’s participants remains an unresolved question, which will perhaps be answered next year if this unconventional but complementary consortium of fairs returns.