Ojo en rotación: Sarah Minter, imágenes en movimiento 1981-2015

March 14 – August 2, 2015

Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, DF

Spinning (2006) is a logical beginning for a survey exhibition of an artist whose practice was galvanized by the 1985 earthquake that devastated Mexico City. Leveling buildings and killing thousands, the quake forced citizens to hodge-podge makeshift systems for survival when the government failed to rescue the shaken metropolis. Spinning first takes stock of what still stands in the city’s view, and then whirls it into oblivion.

Exhibited in the hallway of the brutal-ish glass and concrete MUAC, Spinning is a series of seven screens displaying the shifting view of the urban sprawl of Mexico City from the world’s largest rotating restaurant set curiously askew atop the World Trade Center: an anachronistic symbol of folly in Mexico City’s checkered history of urban development. [1] Moving across the screens, left to right, the speed of the rotation increases until the last screen is practically indecipherable, a blur of urban grey peppered with occasional visual thwaps of the restaurant’s support beams interjecting the view. Then the sliding glass doors yawn open and the viewer trips dizzily into what looks like some kind of vidéothèque cemetery, MUAC’s survey exhibition of the work of video art pioneer Sarah Minter.

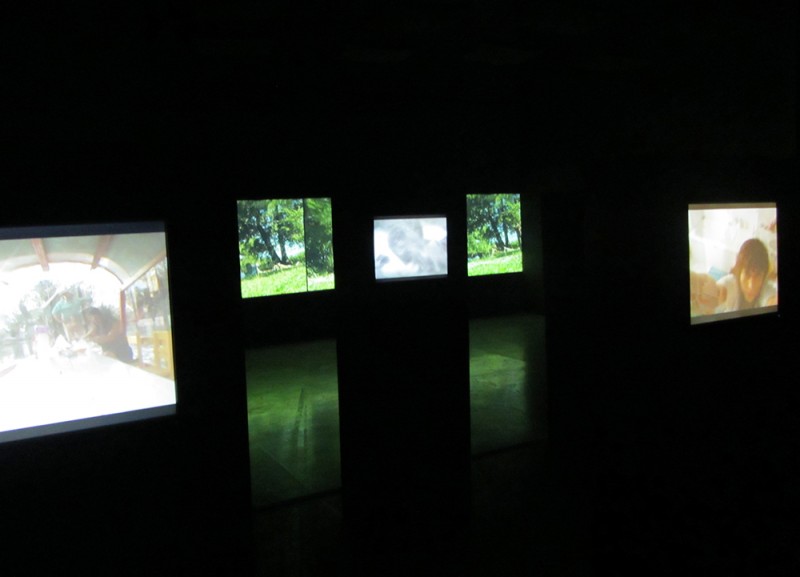

Sarah Minter. Installation view of “Intervalos” at MUAC/UNAM, 2015.

The first of three salons is a dark room featuring an arrangement of 16 plinths each with an LCD screen showing Intervalos—Intervals (2001-2004), a series of short works broadly thematically linked by their distinctly undramatic contemplative recording of daily life: hanging laundry, picnics in the park, lovers taking a bath, Minter milling around a home office. Across the front wall, a 3-channel video shows a group of people in various states of undress, picnicking and wandering past the camera. There’s no distinguishable dialogue, and we are merely invisible observers permitted view of their frolic in the landscape.

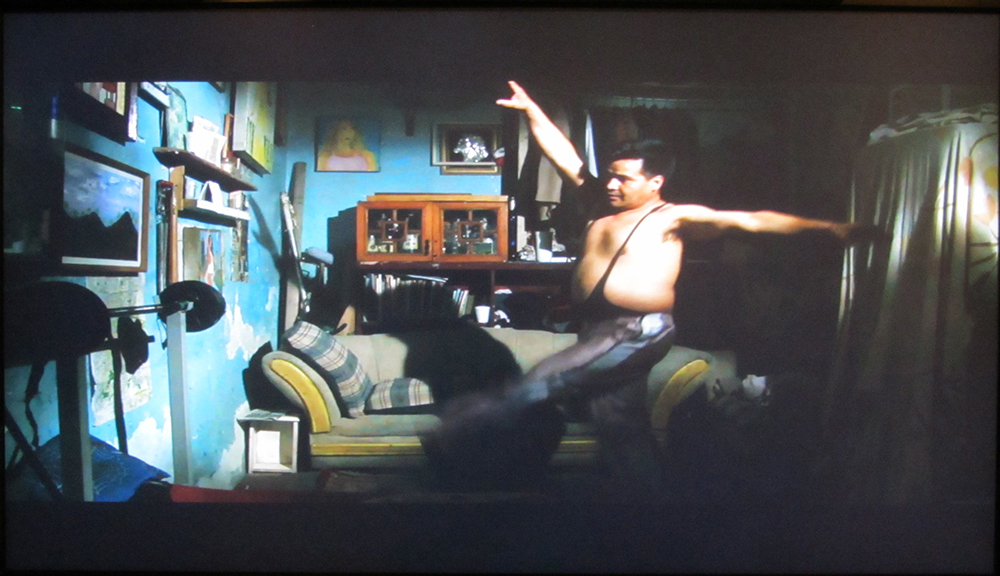

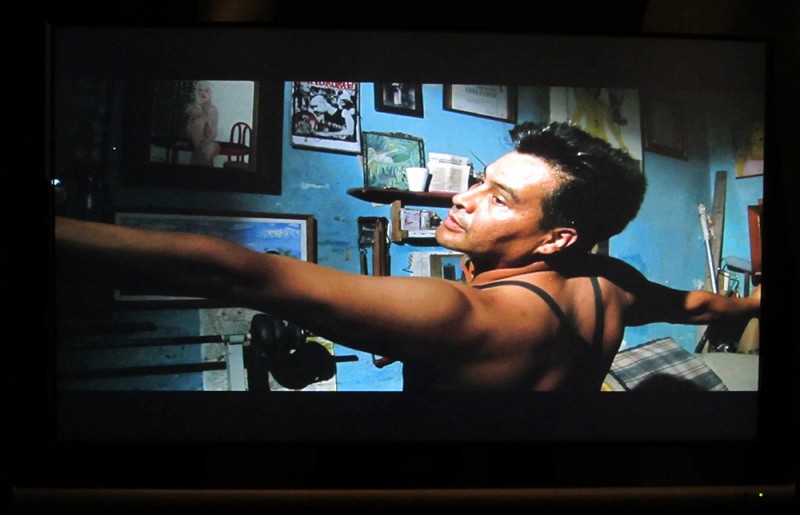

Sarah Minter. Still from “Minueto” 2014.

Drawing on her experience in ‘70s theater with experimental director Juan Carlos Uviedo, Minter often uses her and her subjects’ bodies and sense of self as sites of risk. In Minueto (2010-2014) a middle-aged punk from one of Minter’s works 20 years prior indulges in a moment of classical ballet, giving his whole body and being to a piece of music incongruent with what we imagine an aging anarchist from a marginalized community would listen to in his moment of privacy. In Self-portrait 1 (2001) she twirls, perhaps dancing with her camera à la Pola Weiss, but the image of her smiling face degrades, spliced with images of static (or is it outer space?), blurring until the face has transformed from self to demon twin, summoning the Beezlebub within.

Minter’s work is at its best when it uses observation to wrestle the psychic specters of urban existence. Pieces like One-Day, One-Night Trips Through Mexico City (1997) offer the sense that the city itself that has become the monster. It’s citizens are cast as under-dog Davids, heroes holding back the megalopolis from devouring them by performing their small everyday rituals, knowing at any second the city could swallow them whole, as in ‘85.

Sarah Minter. “Ojo en Rotación,” 2015. Video Installation.

The show culminates with Ojo en Rotación—Rotating Eye (2015), a cube-shaped video installation of Minter’s wanderings through Mexico City commissioned for the exhibition. The cube is displayed in front of Adrift/The Ship (2010-2015), Minter’s animated rendition of Manuela Generali’s painting the Barco Maya—Mayan Ship (2010). One wonders if Minter is suggesting that this block is being fueled, dragged or anchored by the simulacra of massive ship sailing ever forward.

Sarah Minter. Installation view of “Ojo en Rotación” and “Adrift/The Ship,” MUAC/UNAM, 2015.

Fuel or anchor, the ship belongs to Mexico’s national oil company‘s fleet, therefore, it is unquestionably linked to Ojo en Rotación and to the museum. Pemex serves as the nation’s coffers, funding, among other institutions, the Autonomous National University of Mexico (UNAM), and the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC), but the political origins of this subsidy with its inevitable ideological strings have earned the moniker “golden handcuffs.” The muralist scale and “bad” animation of the ship deploy outmoded technologies, perhaps in reference to ham-fisted manipulations of Mexican art history, as well as the frequent clumsiness with which citizens talk about, and thereby construct, notions of power dynamics regarding a state (and company) notorious for opaqueness.

Rotating Eye is projected on and through five sides of a large white cube. The piece can be viewed from outside as a monument-like block of moving images or from the inside as an immersive experience. To enter the cube is to scramble inside Minter’s head, like a virtual reality alternaverse we occupy her eyes, seeing what she sees as she moves through the city; the camera shifts, shakes, pans, and bounces with her movements. We don’t know what kind of apparatus was used to film the piece, but the people taking photos of her in the film and her occasional cast shadow suggest it was a DIY contraption fixed to her head, referencing the 9 eyes of Google as much as it does anthropology, performance art, and urban studies. Lost in the world of the cube: moving from streets, to mercados, from downtown dance halls, and an uptown luxury mall, finally to last year’s historic protest at the Zocalo; the ship’s horn sounds from the outside—a reminder of the devil in Mexico’s Faustian bargain of state-owned natural resources to which the cube and by extension its citizens’ bodies, security and freedom are yoked.

Sarah Minter. “Háblame de Amor,” 2013. Video Installation.

Minter’s videos are not mere recordings of social change or quotidian boredom; they are works born out of the needling tension between the city and its inhabitants, using daily ritual as opportunity to create an emotional possibility through non-narrative. Minter says of the 1990’s there was “a certain suffocation in this city”[2]; her work serves to construct emotional breathing room for choking citizens.

—

[1] DePalma, A. (1994, November 24) Mexico City Journal: Don Manuel’s Dream Tower: A 50-Story Folly? The New York Times

Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1994/11/24/world/mexico-city-journal-don-manuel-s-dream-tower-a-50-story-folly.html

[2] Delgado, C., Henaro, S., Minter, S. (2015) In Dialogue with Sara Minter MUAC, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, UNAM, Mexico, DF pg 148