Corin Sworn: The Rag Papers

July 2–August 2, 2015

Western Front

303 East 8th Ave. Vancouver BC, V5T 1S1

Do you like old things?

Because film installations don’t inherently demand the same punctuality required to attend the cinema, we’ll often enter into the film partway. While we wait for the film to loop, we usually experience the end before the beginning. Does this (dis)order of encounter ever compromise the intention of the artist-filmmaker, the hours editing, deciding that this comes before that, or that comes after this? In film, we seem to be consistently hard-wired for chronological order, that is to say, for narrative to reveal a train of ordered events. Corin Sworn’s The Rag Papers, a 20-minute film installation with synchronized lighting, disrupts chronology and rearranges filmic expectations, leaving the viewer to reassemble a narrative at their will. Akin to experiencing an album on shuffle, Sworn’s disruption of a linear understanding, manifested as a compilation of heterogeneous motifs, overthrows whatever sequential predisposition we may arrive with.

By the light of the faintly glowing projection, the screen is paused on black and a narration, peppered with dialogue and prose, proceeds to unfold an ambiguous relationship between strangers. The first aspect of the film I encounter is during the narration, when, upon entering this installation in the Western Front’s Luxe Hall, the voiceover asks, “Do you like old things?” This is the tagline for my experience of the film. Throughout the spoken segments, a cohort of glass light fixtures suspended from the ceiling performs a concert of warm light.

Corin Sworn, The Rag Papers, 2013. HD video installation with synchronized lights (video still).

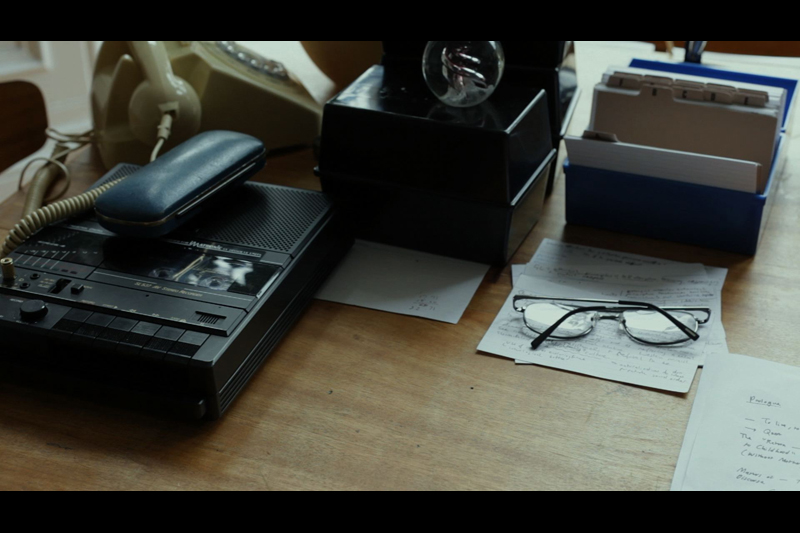

Once the film ends, the Luxe Hall’s lights go up and the projection turns off, hearkening to cinema’s conventional prompt for the audience to vacate the theater, an unorthodox measure in gallery film installations. When it begins again, the screen fades from black to reveal a home office with a small desk, overcrowded with artifacts of belletristic work. Sworn developed the piece with two sets of actions for separate actors who were each filmed by a different documentary filmmaker. Sworn intercuts this footage between a middle-aged man and younger woman who handle the objects in the room with evidently different motives. With an assortment of short takes, hands grasping documents and expressions conveying quiet trials, this sequence conjures Hollywood tropes of a tension between a hardened man and femme fatale. The man handles file folders, index cards, peels an apple from a bowl of fruit on his desk, smokes cigarettes, listens to records, gazes out the window, and never speaks. His treatment of the space connotes that it is his. The woman is shown entering the room and states, “I take full responsibility” to another person just outside the apartment scene. She commences excavating the man’s belongings for something specific, unconcerned with leaving evidence of her visit. She receives a call on her cellphone, and declares, “He isn’t here” and “I have looked.’ Her role could be anywhere on the spectrum of an obsessed PhD Candidate (presuming that the man is an important scholar) to a nosy family member or perhaps a personal assistant sent on an errand (she checks herself out in the mirror atop the mantle and takes an apple on her way out, giving her intrusion a very casual quality). Whatever drama Sworn implies remains relatively opaque. He’s left his record player spinning; she pushes the needle aside, suggesting that her presence has come after his in Sworn’s script. Addicted to narrative as we are, we want to establish a link, even a tenuous one, despite knowing that the two sequences were developed and filmed autonomously, and edited only to suggest a narrative connection.

Corin Sworn, The Rag Papers, 2013. HD video installation with synchronized lights (video still).

In a daringly abrupt shift in style, the film cuts to documentary footage of thrift store shoppers mixed with footage of rag yards where articles of clothing are sorted by color and compounded into massive bricks for global transport. With the decision to show the shop before the factory, this segment replicates (without metaphor) the order of a pedestrian secondhand store encounter, in the way we usually arrive at the point of retail, before we’ve begun to consider thinking, usually much more romantically, about the past lives of objects. The tendency is to mine eccentricity, to extrapolate the possibilities of its previous use and owners, rather than confronting the more immediately prior grit of commercial processing. The sequence is not so much a moment of righteous consciousness about the underbelly of commodity culture, but how would we reconcile that with the other content in the film? It is a depiction of movement that is typically lost in an earnestness to repurpose the past.

As if sourced straight from the charity shops Sworn filmed, an arrangement of glassware appears against a black background; more vessels in varied shapes and sizes are slowly introduced into the frame. Sworn lit this accumulative still life in such a way that the addition of each glass visually stacks stark white outlines of cups, but its objecthood is reinforced when each addition lands the crisp, minimal sound of glass on glass. The glassware speaks formally to the light fixtures that flashed during the narrative, forging a material connection with the content of the film and the fixtures in the room.

The Grand Luxe Hall at Western Front, Vancouver.

The screen darkens and another narration and light play commences. By breaking film’s convention of darkened spaces and uninterrupted attention, this perhaps might function to garner spatial awareness of other presences in the room, or the room itself. It’s not breaking the fourth wall, but doing something to that effect. In the space of her Western Front installation, it’s not necessarily a stark, neutralized room that is exposed back to us. Previous to being established as the Western Front in 1973, the gallery’s building was the lodge hall for the local Knights of Pythias. The Luxe Hall is a room that is very historically pronounced, and despite some structural renovation over the last forty years, has quite successfully maintained the contours of its history. To be in any part of the Western Front, with the exception of its white-walled exhibition room downstairs, is to be aware of its past-life in a way that is obliterated in white cubes. As a by-product of the site, past lives and romanticism linger as a consequence of spatial awareness.

Corin Sworn, The Rag Papers, 2013. HD video installation with synchronized lights (video still).

In The Value Village Lyric, poet and philosopher Lisa Robertson lavishly catalogues inventory, intention and malaise in the eponymous department store. A mélange of sentiment and pursuit are borne of the poet’s desire to wear the histories disavowed cloth, “It proceeds by dissociation and division, we observe the simultaneous proliferation and cancellation of origins, we adapt to a random texture…[we] try it for fit.” Sworn’s narrative attends to this kind of misalignment between an object and its adopted context, a metaphor for extrapolation at the sight of assembled signs: “She said she’d know him reasonably well, as well as anyone did, and this turned out to be very little/Phrases replaced what have been full-length stories, and those repeated, looped, trailed off/It’s a tattered text, more of a collection of possibilities than anything of substance…”

The phrase eventually comes again, “Do you like old things?” I do like old things.