ZERO – Let us Explore the Stars

July 4 – November 8, 2015

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Museumplein 10, Amsterdam, Netherlands

ZERO was the title of a magazine published by Otto Piene and Heinz Mack from 1957 to 1967. It also was the name for a radical European art movement started by Piene and Mack in Düsseldorf and that quickly spread to the Netherlands, France, Belgium and even as far as Japan and South America. The name ZERO promised the chance for a new departure, a clean palette and an escape from the still lingering effects of WWII. ZERO promised the chance for a new future for art, propagated radical use of material and media, and in the process profoundly shook up the way we think about art. A new kind of artist was born, one that wore suits, one that planned and documented their work, one that knew how to make use of public relations.

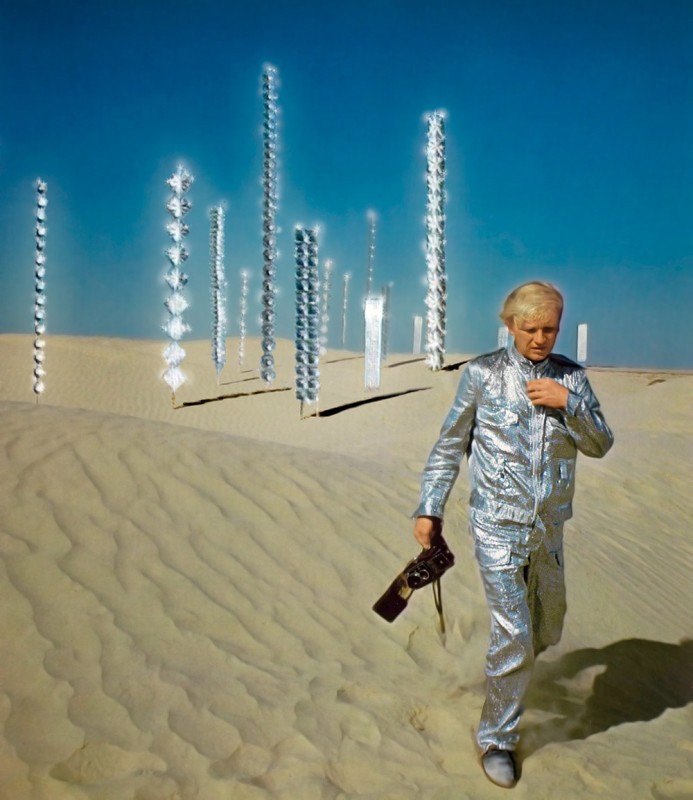

Heinz Mack during the shooting of the film TELE-MACK, 1968, photo: Edwin Braun.

The Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam was closely involved with the movement pretty much from the start and pioneered the exhibiting of this new kind of extreme and subtly subversive art as early as 1962 and again in 1965, shortly before the network disbanded. Precisely 50 years after that second and last show that focused on the Japanese Gutai branch of the movement, the Stedelijk now honors the group with a retrospective full of light, reflections, machines, and a wealth of documentation.

Appropriate to its title, the show occupies the bottom level of the Stedelijk’s new annex. It is connected to the upper galleries by a spectacular escalator, which to ride is to take a long journey into the light and could, itself, be part of the exhibition.

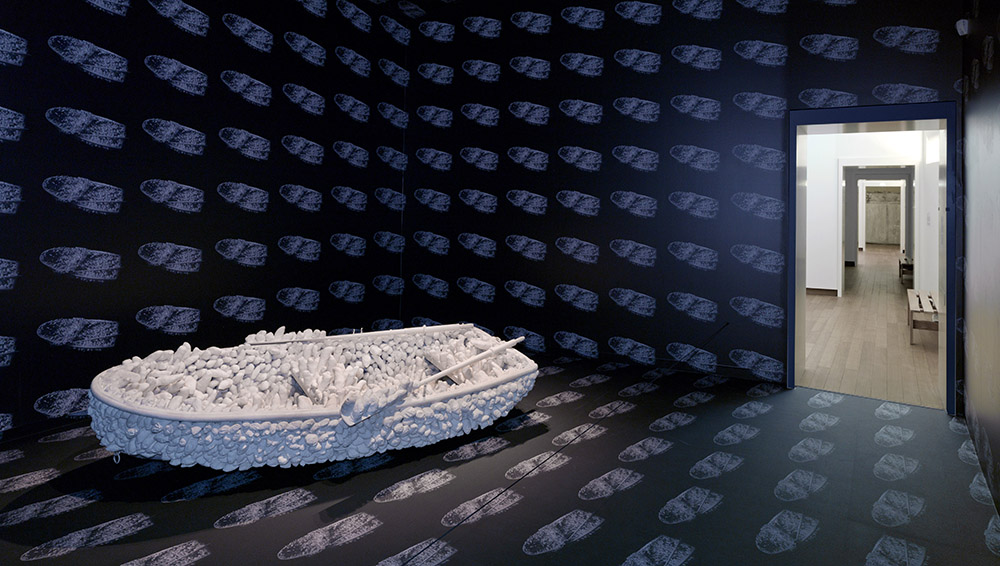

ZERO – Let Us Explore the Stars, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 2015, installation view. Photo: Gert Jan Van Rooij

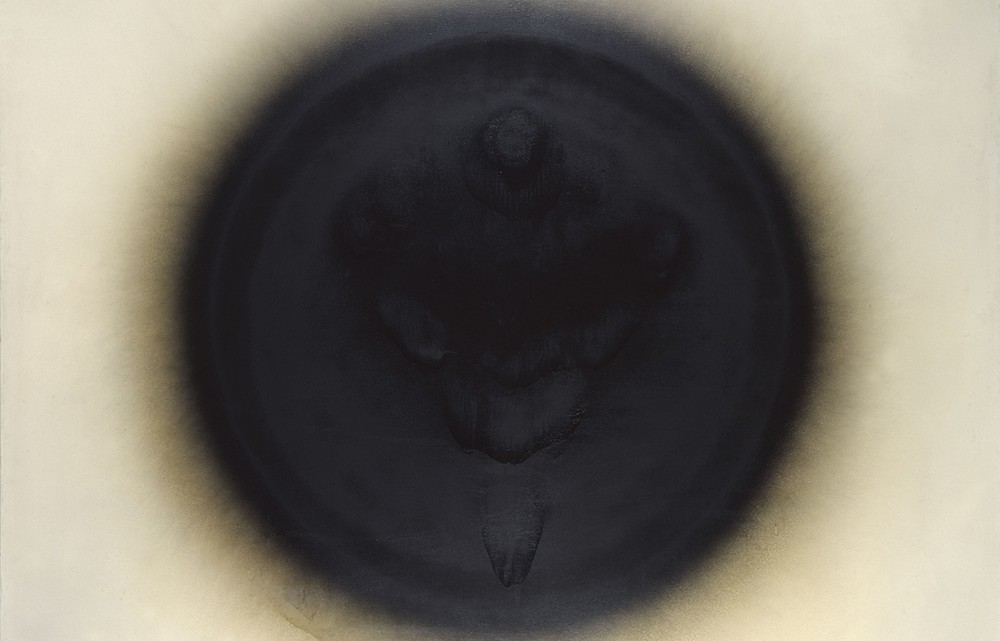

The first room focuses entirely on the white works that are considered the most iconic of the movement. White, in all its shades and variations. constituted the ZERO signature palette and while restrictions in art were not a new invention, the ZERO group took the white works to such an extreme, in shape, size and fervor, that it became the basis for their artistic renewal: white being ZERO pigment, a new point of departure. There are white paintings in all shades, shapes and sizes, textured, manipulated, the canvases twisted and ripped. There is a box of white light, white reliefs with painted nails, fur, cotton balls, installations of water and ice.

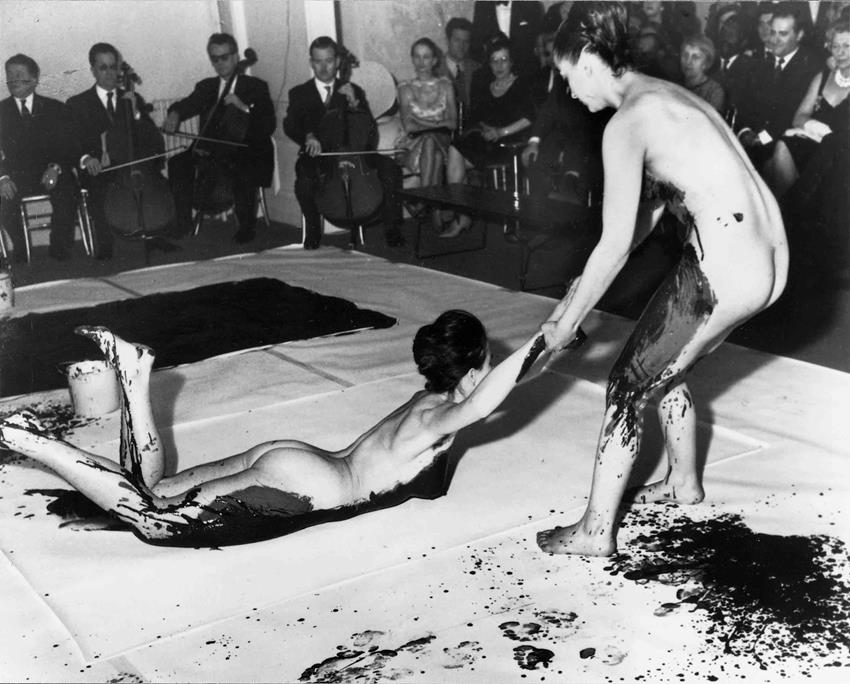

Yves Klein, “Anthropométries de l’époque bleue, 9 March 1960.” Galerie internationale d’art contemporain, Paris, France, Artistic action of Yves Klein © Yves Klein / ADAGP, Paris / Pictoright, Amsterdam, 2015 Collaboration Harry Shunk and Janos Kender © J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. (2014.R.20) Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kender

Light was another ingredient used by the group and it was treated as a medium in every way imaginable. In the exhibition, there are complex sculptures and installations with mirrors, arrays of machines that enact entire “plays” with motors and light projection, as well as films that work solely with light and the absence thereof. Conceptually, ZERO offers the act of reduction to the most elementary ingredients, in their objects as well as in their actions, performances and gestures. The artists confronted water with air, painted the audience, and took art into nature like Mack did when he decided that a place like the Sahara desert in her unbelievable vastness would be the perfect place for a new start for art.

Yayoi Kusama, “Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show,” 1963. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Thanks to the well-organized nature of the movement, many performances, actions, and publicity films are documented and on view at the Stedelijk. While most of the exhibits on display are from artists of the German and Dutch branches of ZERO, there are also some works by artists of the Japanese Gutai branch including Akira Kanayama’s object Boru (1956) and Yayoi Kusuma’s Boat (1964)—a white boat covered with plaster phalluses—as well as a video of one of her polka dot performances.

Akira Kanayama, “Boru,” 1956. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

A new start from ZERO is what this movement wanted to achieve and even though it was relatively short-lived, their influence on art was profound and may only now be reaching its apex with the works of the ZERO group selling at unusually high prices at auctions. The time may be ripe for yet another new beginning—this time a departure from the gimmicky sensory overload and empty irony proliferated by postmodernism and digital media. While this new break will undoubtedly take a new and unknown shape, conceptually, the ZERO group may still be leading the way.