Alex Bacon met with Elaine Cameron-Weir in her Brooklyn studio to discuss some of the issues at play in and around her work. Structured less as an investigation of Cameron-Weir’s biography, the iconography of her work, or the physical processes that create it, this text captures instead the wide-ranging discussion they had of the issues behind, raised by, and surrounding the work. They move through a plethora of topics that came up along the way, including New Age aesthetics of symbolism and telepathy, the role of politics and discourse in art, and visual versus spoken language.

How do you come to make a sculpture? Is it that you’ve encountered a material and you’re excited by it in some way, or do you have an idea and then you find the appropriate material?

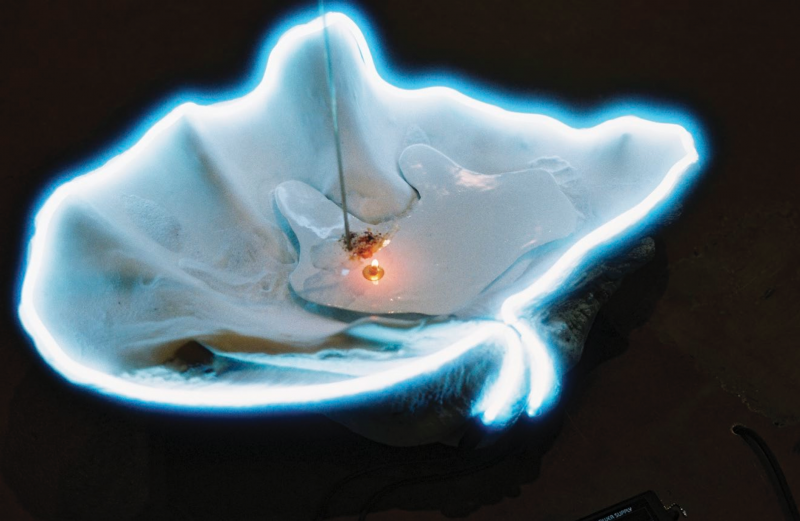

A combination of those two things. I used to play around with materials a lot more. I don’t do it as much now, but I still do it sometimes—for example, the show that I did with the clamshells and the neon. I didn’t know what those were going to be before I bought the shells.

Did it come to you as an idea, or did you see a clamshell somewhere?

I knew that I wanted an object that could hold something. The whole set up for the sculptures in that show came to me while I was doing something else. I was actually sawing metal, thinking about another show. I had already ordered these giant clamshells and I got this fully formed idea for them and thought, “I’m going to go with that.” That doesn’t happen too often for me—that something just enters into my head when I’m not necessarily thinking about it—but that’s one way that it does happen. Or sometimes I have dreams about something, like the desk piece I recently showed at GAMeC in Bergamo, Italy. That was based on a dream that I had while I was in Istanbul.

Venus Anadyomene 5, 2014. Giant clam shell, sand, neon light, transformer, ceramic olive-oil burning lamp, mica, brass, incense. Shell approx, 32 x 18 x 8 inches, other, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

Would you say you set up situations through which this kind of thinking could happen? As a writer, I often find that in writing or talking, ideas happen. Not that it’s intentional, but there’s just something about those kinds of activities that can get the cognitive motor spinning.

That’s definitely true. Most of intuition is learning how that works for you—how you can setup situations that induce ideas. An automatic task can let you think about something else. Sometimes it’s hard to sit and just stare at a wall even though that’s the kind of mindset that might be conducive to this type of non-focused thought. You have to find an activity that allows you to get the staring-at-the-wall brain.

So when you’re doing a banal task that just has to be done, like cutting metal, you’re also thinking?

It’s definitely combined. It’s not like I go into a trance. When I say I’m thinking about work, it could be while doing something super mundane, like with the sawing example, but I’m usually focused on it in my mind somehow. I might be thinking about what a piece would do perceptually for a person looking at it, or it could be “how do I order that part off of the Internet?” It’s all mixed together.

A day dream about the authority of a heavy desk, about other vocations spent behind one ordering certain men around, about domineering and maybe reclining slowly, exhaling, 2014. Terrazzo, stainless steel, laboratory hardware, neon lights, transformers, paraffin lamps, mica, frankincense, sterling silver Tiffany dish. Variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist.

A day dream about the authority of a heavy desk, about other vocations spent behind one ordering certain men around, about domineering and maybe reclining slowly, exhaling, 2014. Terrazzo, stainless steel, laboratory hardware, neon lights, transformers, paraffin lamps, mica, frankincense, sterling silver Tiffany dish. Variable dimensions. Courtesy of the artist.

That makes a lot of sense. I think that today the fetish of the artist as worker has been updated. We’ve become so alienated from labor—especially the classes that are involved in buying, writing about, and exhibiting art—in a very particular way having to do with, among other things, the mediations of technology and the outsourcing endemic to late capitalism, that there becomes a discourse about artistic process that is not intellectual, but rather steeped in a simplistic, nostalgic fascination with how things are made. I feel like there is this dual fantasy of either the artist as genius, an old idea, or this more recent one of the artist as salt of the earth, somehow laboring like a latter-day David Smith in the foundry, soldering steel together. Today a lot of people don’t necessarily need there to be a spiritual aspect, as long as there is a sense that something is being done that requires effort, even more than talent. Or perhaps those things have been collapsed together in the popular imaginary.

I think they’re combined in a lot of ways. I don’t like when people play off of that idea of process as a way to put content in their work when it’s not there. It’s often done that way, and I feel like, as an artist looking at another artist’s work, and then hearing that they did this and that, it can be really disingenuous, because sometimes you can see through it. But a certain audience might not.

That’s why I only really mention the process I use to make things when people ask me how they’re made. But for me it’s not part of the overt reason for those things existing. For example, I don’t explain alongside the cast aluminum works that they’re made by me and my dad in his backyard using salvaged metal from an oil industry junkyard. If those pieces were to have wall text and press releases about North America going to war over oil, it would seem to fill it with content and it would be easy to write and talk about, because you could explain it. But it would simplify them to the point that they’re just boring. It’s also not true. That’s not the sum point of them.

All that said, with the aluminum pieces, I also don’t want to say that these have nothing to do with wars over oil. As an artwork I’m not trying to have them talk about it directly, but they probably wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for the larger situations in the world. Obviously I’m not working in a vacuum—nobody is—but the materials are mainly industrial waste from oil fields, so everything is connected, but I don’t want to exploit that for content. Doing so feels like an art school assignment where you need to have something to say in a group crit so people aren’t confused.

Plate 4, 2014. Aluminum. 20 x 12 x 0.75 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Plate 13, 2014. Aluminum. 20 x 12 x 0.75 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Group of Plates, 2012. Aluminum. 20 x 12 x 0.75 inches (each). Courtesy of the artist.

It makes me wonder then what the role or interest, if any, is for you of the histories of these materials. In the case of the aluminum works there is this very particular history that we’re talking about, one that is charged, and one that has personal relevance to you based on growing up in rural Canada. Are the histories and larger contexts of the other materials you use important in the same kind of way?

They are definitely important, but in a more general way that is not necessarily meant to be specific to me or my interpretation. I think all materials have some kind of association, almost like a symbolism; sort of like a consensus or agreement in culture. Marble has one, and brass has one, and obviously I understand these materials through these lenses too. To go a bit New Age, it’s a shared association or unspoken, almost psychological understanding of a material as an element, as if you took things apart, because most work has discernible elements. Like a leaf—what does it mean in a dream rather than what this particular leaf means to me right now because I’m holding it, looking at it. So there are two ways that these things can exist, and I think one is very specific to a direct experience and one is tied to a broader meaning. It’s always dual; it always exists in two phases at once.

It makes me think that the brass leaf in your work is both of those things. You’re creating this image of the leaf, but then when it’s cut out, and it’s this shape, and it’s put in this piece of marble, it could also be considered the leaf in our hand, because it’s present before us. But in this context, it’s also, depending on the person, the leaf in the dream, because it’s a symbol of something, rather than a functional leaf that grew out of a plant. So it operates in both those ways.

Exactly, and that’s why I mostly make sculpture, I think. Because it’s hard to do that with painting—with painting it’s always the leaf in the dream. It’s a different mindset or something. I love looking at paintings, but I’m more drawn to making sculpture, for sure, because of the duality. With sculpture it’s real, it’s in the world of the human body in space in a more literal way than the picture/ screen of painting. It always looks like something. It’s not ever truly abstract, I don’t think, which I love, but it can be a marker for the abstract—perhaps if it was only something that was not physical, like a scent or something, which I use in some of my work. You can have an abstract scent, but maybe we can only say that because scent hasn’t been categorized in these ways yet; not as many people can pick out as many easily understandable, shared characteristics. It’s like a cloud of sensory information. But sculpture, it’s always real in some sense; we all know how objects are in the world.

Medusa, 2014. Brass, stone. Dimensions variable. Installation view, Medusa Cement building (Cleveland). Courtesy of the artist.

Medusa, 2014. Brass, stone. Dimensions variable. Installation view, Galerie Rodolphe Janssen (Brussels). Courtesy of the artist.

The found object is not part of your repertoire, I’ve noticed.

Obviously I can appreciate it in art from the past, but I don’t think the found object can be subversive anymore on its own. Or at least I haven’t seen anything in recent years that I would consider interesting or subversive that has to do with just putting a found object in a gallery or museum. But I could think of the giant clamshells as found objects, or other elements I’ve used in combinations. But maybe they’re just materials?

That makes sense, and I would have to agree. As Daniel Buren noticed already in the 1960s, the ready-made, by being readable as aesthetic, revealed that the gallery space itself operates like a painted tableau, and the ready-made as a still life of sorts within it.

It’s interesting. That sentiment makes a gallery into something much nicer than it is, like an impression, or sort of like a stage. It’s like the support of a painting. I think those things come and go, those conversations, but I’m wondering if, maybe, it’s happening now. Maybe the gallery is neutralizing itself in a way?

Like you’re not aware of it?

Or that it’s something that is more of a mute standard, like a painting’s stretcher. Which I’m not saying is good or bad, but maybe it’s not so definitive anymore. This is something I think about all the time in a general sense in relation to my work, how things could intimate existence beyond or without the present context in which they are seen, while still inhabiting that context.

I like that idea. Something we were talking about earlier was the material sense of the work that you put in such a space. You used the term modular, and the way that the work in all cases is a set of components that come together, so this wholeness that is suggested in images is not so much the case in the physical experience of the work because you see how the different components come together.

Even in the way you discussed the works you installed, first in an industrial space in Cleveland, and then shipped to a commercial gallery in Brussels, as being the same, when of course, technically speaking, they’re not visually exactly the same. Nonetheless, they contain all the same components as one another, which I suppose is what you’re referring to when you say that. So, in a certain sense, one is looking at multiple variations of the same object, or interchangeable components arranged in different ways. I wonder for you what the interest is in retaining that situation, rather than simply fabricating a singular object.

I’ve always been attracted to modularity, and visible modularity especially, which can be something as simple as stacking similar parts together. In this case it’s all adjustable. I think that part of what you said is a very good point. I say they’re the same, but they’re physically different because the parts are re-arranged; the difference is something I really like—the idea that they will never be the same as they once were, but they retain their wholeness as a group. I don’t know why I’m drawn to that, but I also think that, when things appear to be modular, they appear to be provisional, which a lot of technology is. You can swap out a part that broke on a machine, or repair, replace, or change the pieces of a high-tech device. The most sci-fi thing is a smooth chunk that does something, you know? Or scientists working on computers operated with gas. Something that has nothing visible you can manipulate.

Sharp points lower the required voltage, electric fields are more concentrated in areas of high curvature, phenomena more intense at ends of pointed objects, 2014. Brass, marble. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

Medusa, 2014. Brass, stone. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

It’s become almost a hierarchy indicative of a class system. If you think of the visual fantasy of something like an iPhone versus a cheap phone, Apple products are all about creating this illusion of a seamless, singular object, whereas with cheaper technology you can see where all the parts come together.

That’s generally true, but I also think that underneath this slickness that you’re talking about there’s a hidden modularity, and it’s not just physical to the technology itself—applications, programs, and all the component parts of the device, really. And it’s always been that way with technology, even with something as simple as a hammer, and the question of visibility has more to do with the political side. The connotation of the chunk being something that mysteriously works is the iPhone: it’s flat, it’s shiny, it’s smooth, and it’s using that illusion of having no moving parts, having no components, to project the feeling of it being technologically advanced. The politics of technology are wrapped up in its aesthetics.

I really like the balance you are striking between the known and the unknown in your discussion of your work, its referents, and the larger context out of which it arises. How much of your work do you feel is visible and easily ascertained by the viewer who encounters it?

I think that a lot of what goes on with my work is really private, and that’s the way I like it. So to talk about these issues is more a conversation that we’re having. My relationship to the work is completely different from yours, or from that of other viewers’. A lot of the time I know that I’m just making work to get myself to think about things that I want to be able to spend large amounts of time thinking about. The motivation is not that complex, but the output could be, and a lot of the thoughts that I have when I’m working on things are really exciting to me, and I never share them with anybody. That’s just how it is. I don’t know, there’s no other way for me. I still think the most interesting things about my work are things that I cannot tell anybody else because I can’t quite communicate them with language.

Ozonic Bar, 2013. Collaboration with Ben Schumacher. Unlit neon letters, glass hardware, seaweed. Courtesy of the artist.

Is the work for you, and the act of making it, some sort of machine for thinking, as in what we were talking about it at the beginning of our conversation around the productivity of a “staring-at-the-wall” mentality? By manipulating these materials, or by placing them in a certain way, you are constructing this interaction between object and viewer, which may be based on ultimately private experiences and thoughts. But it seems like, if it was a machine for thinking for you, then it also could be for someone else, and in the same way, where maybe my experience with the work is just as private as yours— but is necessarily different.

Yeah, totally. That would be the most ideal thing that I could imagine, if somebody had that, because how often, realistically, does that happen looking at art? I love it, but sometimes it’s few and far between that you have a really meaningful experience. Maybe it’s different for other people.

I think, though, that I’m not necessarily thinking about destruction or an absence of the capability of saying something. It’s a different way of communication, so it would be like speaking versus psychic communication, where sometimes there are words, but a lot of times it’s pure emotions, or just sensations, that people cannot describe. It’s a form of knowledge, and it’s a feeling, so it’s almost like hyper-communication. It’s something that doesn’t fall back on language because it’s beyond it, not behind it; it’s not absent. I wonder what would happen to language if we could communicate psychically all of a sudden without interfacing through words.

Psychic communication and there was no other communication involved?

I guess any communication that avoids spoken language. Like a sensation of immediacy, the kind that avoids the part of the brain that filters information for us so that we can survive. And you get that when you do psychedelic drugs, or a little bit when you’re in a sensory deprivation tank, strangely enough. Also, maybe when you have a spiritual experience. I’m not operating under the illusion that someone is going to walk into the gallery and be like, “My brain started working on another level when I looked at this thing.” But, hopefully, I’m maybe doing something that could add to the suggestion of that possibility in the world, instead of taking away from it, or blocking it. Or, at the very least, just doing so for myself.