One of the last times I saw Tania we drank a bottle of Blanton’s Kentucky Bourbon and laid on the floor in my living room in Phoenix listening for hours to music tracks by The Electric Light Orchestra, David Bowie, and Pérez Prado through a 1980s sound system with a pair of amazing vintage Bose 901 speakers and really listened intensely to the sounds coming out from every angle of the beautiful wooden boxes. The next morning (I don’t even remember calling a cab for her) we nursed our hangover and went for a hike at a local site called Papago Park and there, in the middle of the park, laid the most magnificent natural red sandstone formation called Hole-in-the-Rock. Tania immediately thought that this hill had some of the same characteristics of the Bose speaker design with its unique shape, openings, and curves and asked me, “How can we convert this six-million-year-old sandstone hill into a sound system?”

This type of inquiry draws me to her work and artistic process. Her research methodology can be regarded as an artist-anthropologist, questioning conventional notions of sight and sound through experimentation in sculpture, sound, language, and science. A prime example is one of her recent projects at Laboratorio Arte Alameda in Mexico City entitled Cinco variaciones de sobre circunstancias fónicas y una pausa (2012), which explored the relationship between machines and language, and the potential of sound, speaking/listening, and writing/coding as materials for art.

Tania’s work has been shown around the globe from Mexico City to Lithuania, Madrid, San Francisco, Bogotá, Warsaw, El Paso, and New Delhi, among many others. Her work is in the collections of Deutsche Bank and the Centro Cultural Tijuana, the Mexican Museum in San Francisco, the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Museum of Latin American Art in Los Angeles amongst others. She is a recent Guggenheim Fellowship recipient and will represent Mexico with Luis Felipe Ortega in the 2015 Venice Biennale.

We are still figuring out a way to transform the Hole-in-the-Rock into a sound system through the cultivation of piezo crystals that can be played by experimental musicians as part of a large-scale public project for the ASU Art Museum. Perhaps next time we need to drink Jamaican rum and listen to some Mad Professor dub music?

A renaissance happened in Tijuana in the late-1990s, and the city experienced a new sense of ownership for a border town that was only known for its sinful past based in American tourism. Part of this cultural movement was founded in the music of Nortec and the arts collective Torolab. Eventually, in 2001, Tijuana was featured on the cover of Time magazine. What did it feel like to be part of this movement, and how did that fuel your growth as an artist?

During the time that I lived in Tijuana, the city was an unprecedented space of freedom for artists to work outside of academic boundaries—it had no fine arts school—which triggered a particular creativity and eloquent language about the present. There was a pushing desire to create that grew organically without institutions in a collective fashion that allowed for interdisciplinary collaboration. And it was not just within traditional fine arts techniques—there was an exchange and enrichment among people doing graffiti, popular music, video, literature, and many other forms of expression, and we were working together. Moreover, Tijuana has a particular aesthetic that awakened my sensitivity to text as form and shape as text, as in the work of taggers and graffiti creators who are the calligraphers of our time. I was interested in working with and thinking about transgression, the subversion of systems, and questioning what art and vandalism are, what is damaging a city and what is giving it life, how to resist the marginal conditions of a border-city and to how transform it into a creative hub.

Tijuana was important to my artistic career. It was full of opportunities and it gave me the platform and the space to start exhibiting my artworks and understanding that everything is valid and it is possible to archive artistic ends.

Finally, what was happening did not go unnoticed and there were a couple of international festivals, such as inSITE, that set the focus of the art world on “the north” and the amount of powerful works we were creating, and how different it was from what was happening in Mexico City.

Your approach to public art in the late-2000s is quite unique, with projects occurring between Tijuana and Mexico City, such as Habitantes y Fachadas, and your collaborations with the graffiti artists that bombed the posh Hotel Habita and the National Library. Do you consider this the beginning of your interest in code and the aesthetics of language? What was the public reaction to seeing these iconic buildings—or, in the case of Tijuana, one of the first planned housing developments—overwhelmed with graffiti?

I would approach it the other way around—it was because of my ever-present interest in language and narratives that Habita Intervenido and Writers y Escritores were possible. Habita Intervenido had an unexpected reaction; it was very successful and appreciated in the high-class neighborhood where it was placed, but to me it was very interesting how changing the context of the same action can turn vandalism into art. In the case of Writers y Escritores, the effect was different due to its location. It was not obvious to the press that it was an artwork, but to the people that lived around the library, that used to feel intimidated by it and by the space of a library in general, the work somehow helped them approach it and understand it as theirs.

Tania Candiani, Habita Intervenido, 2008. Stencil and spray paint on glass. Hotel Habita, Mexico City. Courtesy of the artist.

Tania Candiani, Reinterpretación de Paisaje, Cierre Libertad., 2008. Installation with junkyard materials. Tijuana, Mexico. Courtesy of the artist.

Your interest in music, sound, and technology has been very prominent in your artistic production. Can you talk about the various influences that drove you to this work? Also, what about the lack of female representation within this genre in Latin America?

I was driven to sound through my interest in time, and technology came as an answer to a research need and an expressive need. An exhibition at Laboratorio Arte Alameda, a museum dedicated to media arts, was a great chance to explore those realms and their potentials to address the topics I am interested in researching. The lack of female representation is related to the still very pronounced gender difference in Latin America, with fixed roles that are emphasized in education, and games and toys, resulting in an exclusion of girls and women from the technological sphere. But it is a reality that will gradually change.

Your breakthrough 2012 project Five Variations on Phonic Circumstances and a Pause at Laboratorio Arte Alameda in Mexico City was a phenomenal leap in your artistic practice wherein you experimented with antiquated media and new forms of technology in order to create a “phonic circumstance.” What was your motivation for this body of work?

It was an interest I already had, but it was the chance to work in an art and technology museum that triggered a wide-range exploration of media. My motivation was to explore media archeology, not to work with technology as “the new,” but to understand the deep time of the media; to rethink the past of the machines we live with now. I found automats appealing; our desire to emulate life and human actions and the amazement that these phenomena provoke. The exhibition also continued my interest in embroidery and used graffiti as a cryptic language. It was the beginning of an interest in the obsolete and in technologies that are disappearing. I was trying to bring them to life again, and, in the meantime, to propose a richer understanding of them and what they meant to our societies. I also wanted to think of the process of translation, and the relationships between scores and words, sounds and stories, punch cards and music, and even between what is said and what is understood and written.

Can you describe the importance of “nature” in your work and its impact on the current projects, such as the Boom Rock that we are currently developing together in Arizona with the cultivation of Piezo crystals?

I work to resist the appropriation and subduing of nature in destructive ways, to question standard discourses and the normalization of these processes. And I work by linking science and art, appreciating both nature and culture as sources that lend their power to aesthetic proposals. Reactivating those moments of intense dynamism between science and art can only leave us with questions that depart from superficial layers or simple empirical observations in order to act as generators of creativity and promoters of new aesthetic experiences. That was the premise for La Magdalena. I was exploring the methods of observation and empiricism to expose a human desire to contain nature in a wunderkammer. In the case of the Boom Rock, this whole approach is turned into wonder for nature. It is a technological piece based on the possibility of cultivating a speaker, and in the end a return to nature.

Tania Candiani, Sobre el Tiempo, 2007. La Salada Desert, Baja California, Mexico. Single channel video. Courtesy of the artist.

Tania Candiani, Wooden Trumpets, 2014. The Glenfiddich Artists in Residence program, Banffshire, Scottland. Installation and video. Courtesy of the artist.

You and Luis Felipe Ortega are representing Mexico in the 2015 Venice Biennale; can you give us a sneak preview of the project and collaboration?

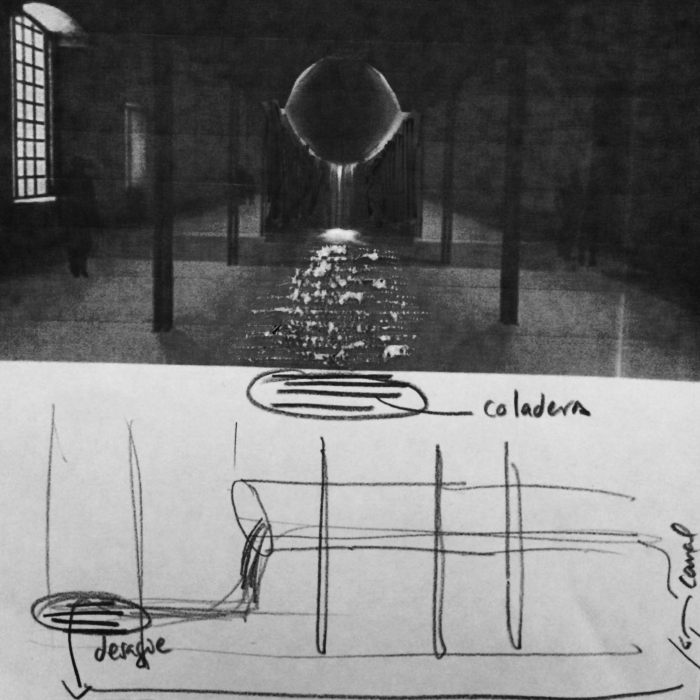

Possessing Nature, as the title suggests, is about a desire to own and control that has proved destructive and catastrophic. It is a very critical work that builds metaphorical and physical lines with the recent history of Mexican pavilions in the Venice Biennial. It approaches both Mexico and Venice as “amphibious cities”—it reads their public policies and the results of the life of their inhabitants and nature. It departs from the simple gesture of tracing a route and raises it to make it present in the Venice Arsenale. It is the shape of a canal, and is a metaphor of a useless system that feeds itself from the lagoon and throws the water back again. It refers to monumental scale. It works through sound. It reverberates as a critique to the obsession of control and possession of nature.

Tania Candiani and Luis Felipe Ortega, Sketch of Possessing Nature, 2015. Forthcoming installation at the Venice Biennale. Courtesy of the artists.

More discussion of Possessing Nature at the 2015 Venice Biennale:

At the Mexican Pavilion, Artists Mine the Geopolitics of Two Fast-Sinking Cities

Tania Candiani & Luis Felipe Ortega to represent Mexico at the 56th Venice Biennale

The Venice Questionnaire 2015 #32: Luis Felipe Ortega and Tania Candiani