Raymond Pettibon

From my bumbling attempt to write a disastrous musical, these illustrations muyst suffice

April 23 – May 30, 2015

Regen Projects, Los Angeles

6750 Santa Monica Boulevard, 90038

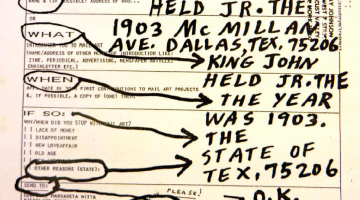

To dive into the work of Raymond Pettibon is to dive into the heart of darkness. That darkness is the heart of America. Over three decades, Pettibon has completed over 20,000 unique drawings of a range of subjects, from the wistfully existential to the fatuously pop. His new exhibition at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, From my bumbling attempt to write a disastrous musical, these illustrations muyst suffice, addresses favorite Pettibon themes like surf culture, rock n’ roll, baseball, the U.S. military, politics, and film noir, as well as familiar characters like George W. Bush, Joan Crawford, and Gumby, all rendered with brush and ink in comic-strip style. As Benjamin Buchloh has argued, in the work, the celebrity image and commodity cult of America are cast back to the viewer in a distorted mirror. Through this glass, Pettibon reflects us darkly, not as we would like to see ourselves, but as we truly are.

Installation view of Raymond PettibonFrom my bumbling attempt to write a disastrous musical, these illustrations must suffice at Regen Projects, Los Angeles. April 23 – May 30, 2015. Photo: Brian Forrest. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Installation view of Raymond PettibonFrom my bumbling attempt to write a disastrous musical, these illustrations must suffice at Regen Projects, Los Angeles. April 23 – May 30, 2015. Photo: Brian Forrest. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Like many of his prior gallery shows, Pettibon’s latest exhibition features recently completed work. A wide variety of drawings and collages in both black-and-white and color were all completed this year. As pudding proof of Pettibon’s prolific output, one gallery wall is dedicated entirely to drawings of Gumby, which were finished the day the exhibition opened. The show begins with a series of black-and-white panel drawings rendered in the cheerful style of Sunday “funnies.” But the disjointed narratives and vulgar dialogue in these strips are far from sanguine: long-forgotten characters from Charles Manson’s “family” chat in the nude about sex, murder, infantile drug abuse, and necrophilia. Some have read Pettibon’s frequent depictions of the Manson family as a disenchanted criticism of the failures of hippie culture, of its naïveté and hapless hive-mind that would spawn a class of silver-haired and silver-tongued Gordon Geckos not much more than a decade after the Helter Skelter murders. But the artist’s attitude towards the 1960s is complex, and like all his subjects Pettibon draws it with a certain critical detachment, creating what could be an illustrated guide to Joan Didion’s seminal essay on the San Francisco Acid Wave, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (yet with none of Didion’s Manhattanite censure).

Visiting the exhibition at Regen Projects is a bit like watching a book unfold before you—a graphic novel, perhaps—only to see the pages tear themselves from their binding, crumple, rip apart, and reassemble in new combinations of word and image. Pettibon began his career as a political cartoonist, and later as a maker of mimeographed serial zines, but he’s preserved little narrative continuity in his present practice. There’s a legend about William Burroughs cutting up newspaper strips high on junk in a Marrakesh apartment while writing Naked Lunch, and Pettibon’s work reads much the same way—though instead of newspapers, Pettibon clips from Marcel Proust, John Ruskin, Art Clokey, and Donald Judd.

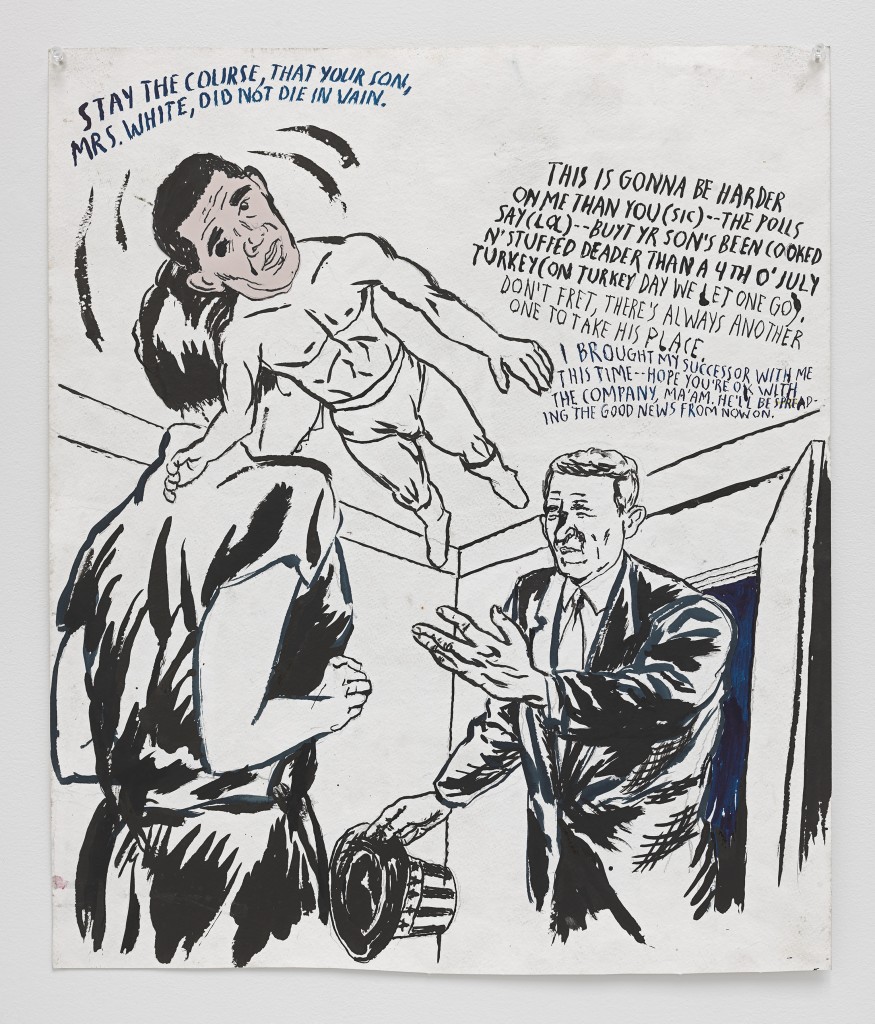

Raymond Pettibon. “No Title (Stay the course),” 2015. Ink, pen and collage on paper. 21 1/2 x 18 inches (54.6 x 45.7 cm) © Raymond Pettibon. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

The works at Regen Projects are tacked up casually on the wall, like the infamous posters Pettibon once designed for his older brother Greg’s band, the seminal punk group Black Flag, which were staple-gunned to telephone poles all over Hermosa Beach in the late 1970s. Through the graphic language of comic strips and the display format of DIY public notices, Pettibon’s work has retained a deeply democratic sensibility. His message is particularly accessible in the political drawings, where his desire to spread the ugly truth about American governance feels like an unassailable ethical priority. In several of these drawings, Barack Obama—now late into his Presidency—becomes a new target of Pettibon’s searing criticism, laid bare as an ineffectual rhetorician who continued the failed defense policies of his predecessor. In one drawing, George W. Bush throws Obama in a Hail Mary pass to a grieving mother. “I brought my successor with me this time,” reads the caption above Bush’s head as he bursts in through an open door. “Hope you’re OK with the company, ma’am. He’ll be spreading the good news from now on.” Clad in a Superman suit with one eye blackened by ink (gouged out by Kryptonite?), Obama drones a message of condolence like an action figure with a talking string: “Stay the course, that your son, Mrs. White, did not die in vain.” For those familiar with Pettibon’s vitriolic output during the height of the Iraq War, when he treated the Bush Administration like George Grosz did the bloated and war-mongering Prussians after World War I, this corner of the exhibition says much about Pettibon’s politics in a time of U.S. drone strikes and domestic counter-terrorism abuses.

Installation view, From my bumbling attempt to write a disastrous musical, these illustrations muyst suffice, Raymond Pettibon at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, 2015. Courtesy of Regen Projects.

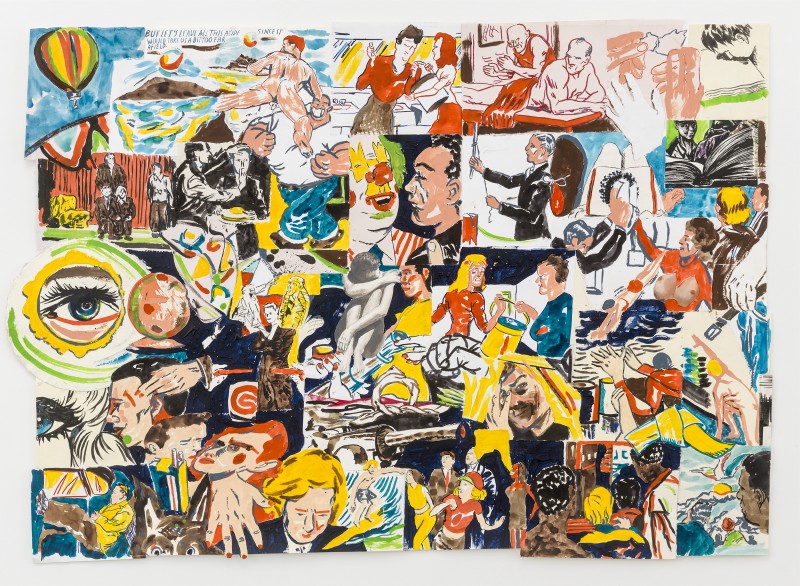

The most impressive pieces in the exhibition are large-scale paper and ink collages in the tradition of early Dada works by Richard Hamilton and Hannah Hoch. In a nod to Hamilton, some feature twisted and engorged bodies in athletic and erotic poses, seemingly drawn from pornographic videos and Olympic sport magazines. Hands, feet, eyes, and fingers all collaged to touch each other create a cacophony of human contact; their shorn paper edges and ink washes are colorful, chaotic, and sensual all at once. Like Hoch’s collaged indictments of toothless Weimar Republic leaders, Pettibon’s collages cut like a kitchen knife through the American promise of entertainment and consumption. The collision of so many dynamic drawings reminds us of the Brave New World side to this promise: in Pettibon’s America, pleasurable urges are satiated and servitude is assured.

Raymond Pettibon. “No Title (But let’s leave),” 2015. Ink and acrylic on paper. 41 1/2 x 58 inches (105.4 x 147.3 cm)

© Raymond Pettibon. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Pettibon’s work originally reached the public as reproductions, Xeroxed and mimeographed in poster and zine form. This makes collage a natural turn, even though the artist’s cut-outs aren’t photographs and ads clipped from magazines, but original drawings, cut or torn and reassembled to form new aggregate compositions. In a way, Pettibon’s drawing process is a simulated collage, mirroring the cut-and-paste technique of postmodern novelists like Burroughs and Kathy Acker. He draws incessantly from television, magazines, newspapers, and the illustrations in pulp fiction detective novels, keeping “dead files” of images to revisit later. Like a magic sieve, Pettibon sifts through this stream of information to create final pairings of image and text, which bristle with characteristically dark and jagged humor.

At Regen Projects, Pettibon manages to sink us in a pit of existential despair, while just feet away he cracks us up with Gumby and the Cracker Jack Kids spouting sexual innuendos. That see-saw effect is part of his power, what Julia Kristeva has called a “dark caricature”—it draws us in with morbid and bemused fascination, at this twisted comedy called life. Cast through that strange distorted lens, the America that returns to the page and the gallery wall is itself distorted, yet somehow truer than its original form. A Frankenstein’s monster whose shape reflects not the literal body but its soul.