Crossroads 2015

SF Cinematheque

April 10-12, 2015

Victoria Theater 2961 16th Street, San Francisco, CA 94103

In its sixth year, the San Francisco Cinematheque’s Crossroads festival of film and video still felt more an exploration than a showcase. Curator Steve Polta arranged the festival’s group programs such that each shuffled established names and upstarts, with multiple works by several lesser-known artists sprinkled across the weekend (I was especially intrigued by Argentine filmmaker Pablo Mazzolo’s feverish insinuations of the 8mm and 16mm camera as a kind of divining rod). More broadly, Polta’s manifest concern with process over product keeps the faith of the experimental spirit of this cinema that is alternatively dubbed avant-garde or underground.

Crossroads reserves a special place for expanded cinema in its Apparent Motion program, but this year’s marquee event was Hypnosis Display, San Francisco filmmaker Paul Clipson’s feature-length live collaboration with musician Liz Harris (who performs as Grouper). The two worked in parallel for the piece, collecting images and sounds evocative of the great American nowhere. While undoubtedly reminiscent of avant-garde odysseys, such as Bruce Baillie’s Quixote (1965), Hypnosis Display often seemed to be burning through the dreamed-of interstices of a thousand road movies and urban thrillers. Clipson has collaborated with many drone musicians, but the particular qualities of Grouper’s sound—intimate and unfathomable, like a memory surfacing after years in the dark—made for a special fit. Her selective use of field recordings (a barge horn, echoing footsteps) intimated narrative, though it struck me that the film’s images were more songlike than its billowing score. This blurring of sound and image only seemed to be in keeping with the work’s bleeding edge between representation and abstraction, built environment and natural landscape, color and noise, stillness and movement, and, indeed, film and music.

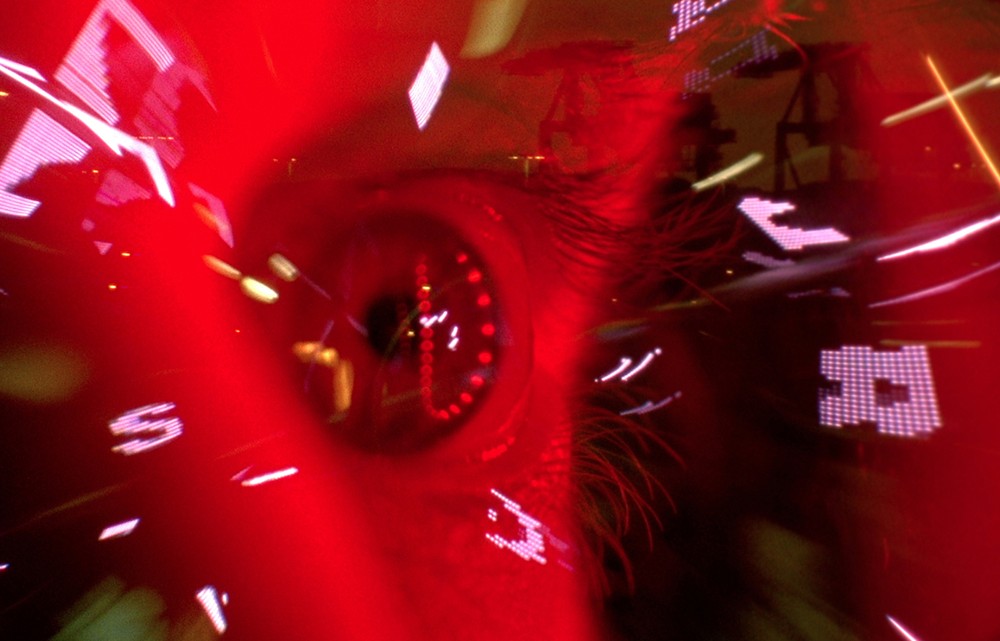

Sylvia Schedelbauer, “Sea of Vapors, Digital Video, 15 minutes

Hypnosis Display might have served as a title for dozens of other films at Crossroads, ranging from the Berlin duo Ojoboca’s nutty exorcisms of found footage to Ben Russell’s characteristically shape-shifting investigation of the transpersonal valences of Swaziland dream rituals (Greetings to the Ancestors). The weekend leaned towards the stroboscopic sublime, with an enveloping or otherwise pulsating drone soundtrack more often than not deployed as a blunt instrument to unify the senses. A clear standout was Sylvia Schedelbauer’s Sea of Vapors, in which a distinctly circular flicker effect floods the crisis-prone parts of the brain with images of intense and cryptic beauty. If Godard famously found the cosmos in his cup of coffee, Schedelbauer takes a similar point of departure in rousing the sleeping dragon of the unconscious, frame by frame.

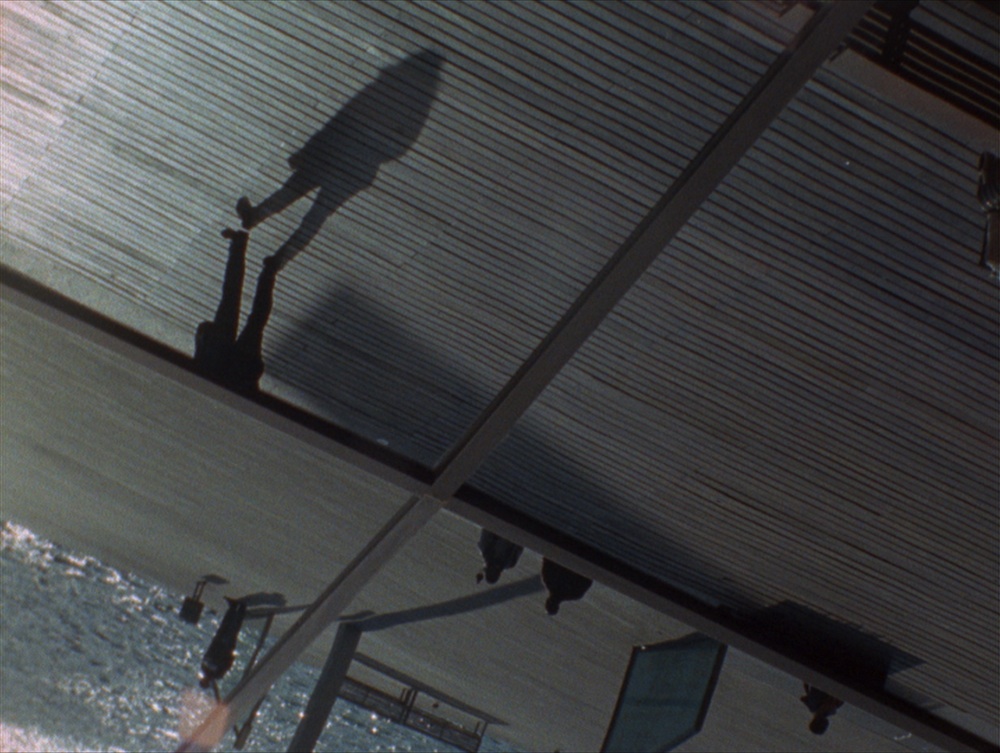

Vanessa Renwick, “layover,” Digital Video, 6 minutes

Much simpler in its formal mechanism but no less mesmerizing was Vanessa Renwick’s layover. The longtime Portland filmmaker trains her camera over an industrial zone for the annual migration of swifts. Their intricate patterns in the sky are frankly awe-inspiring, the kind of thing that moved the poet Robinson Jeffers to muse, “Does it matter whether you hate your…self? At least/Love your eyes that can see, your mind that can/Hear the music, the thunder of the wings” (Love the Wild Swan). Renwick’s coda of a plane streaking across the moon would indeed seem to reflect a renewal of the senses, but I love layover for its hint of frailty: each time the awed camera bucks or racks focus to keep up with the flock, it’s a reminder of our human weakness for wanting to hold what will not be held.

Zachary Epcar, “Under the Heat Lamp An Opening” (2014), Digital Video, 10 minutes

Zachary Epcar’s Under the Heat Lamp An Opening flips the script on this cross-species reckoning, with seagull sounds and some tricky shooting in ceiling mirrors combining for a zoological view of homo sapiens spearing luscious tomatoes and sipping wine at a seaside café. The vacation idyll is of course a tried-and-true target of surrealism, but Epcar’s scramble of scale, sounds, and sightlines betrays a refreshing zest for first reality. The film is weightless as Ernie Gehr’s Side/Walk/Shuttle (1991), though it hearkens back further than that to the deeply irreverent but not unkind play on perspective found in Jean Vigo’s À Propos de Nice (1930).

Deborah Stratman, “Second Sighted” (2014), Digital Video, 5 minutes

The sound of flocking birds will forever be linked to cataclysm thanks to Hitchcock, and there were plenty of other examples of eschatological thinking across the weekend. The combination of Jeanne Liotta’s Soon and Deborah Stratman’s Second Sighted on the same afternoon program was especially provocative. Liotta’s piece, commissioned for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Science on a Sphere educational platform, is an artist’s idea of data visualization. In framing NOAA’s hard facts by J.G. Ballard’s scenario in The Drowned World, Liotta suggests that wrapping one’s head around climate change requires visionary speculation as much as scientific observation. Stratman in turn plays upon our susceptibility to disaster scenarios with a graceful montage of suggestive, if ultimately obscure, images from the Chicago Film Archives: the camera zooming out from a woman standing on an abandoned subway platform; a ship tossed in a rough sea; large radio antennae shifting their coordinates; reams of data printouts; and innumerable landscape shots with specific geographic features indicated (or is it targeted?) by pointers. Moving images play such a central role in our imagination of disaster that they really require no specific referent to create their own context: the images in Stratman’s film may be antiquated, but the sense of impending doom is anything but.

Ben Rivers’ puzzling Things approaches its mundane vision of a post-human future even more circumspectly. The film centers on Rivers’ own living space and personal effects, which, as in his earlier portrait of a departed friend Phantoms of a Libertine (2012), are used as a source for collage. Robert Pinget’s modernist novel, Fable (1971), reappears throughout the film, its drained rendering of apocalypse leading ineluctably to the technological shift of the film’s final section—a virtual reality all the more uncanny for appearing oddly out of date.

Sarah J. Christman, “7285” (2015), 16mm, 6 minutes

Things was one of several intriguingly oblique variations on autobiography at Crossroads, many of them shot in 16mm. These included Ross Meckfessel’s montage of statuary and pop music (The Golden Hour), Mike Stoltz’s sidewinding letter from Cape Canaveral (Under the Atmosphere), and nimble meditations on impermanence from Sarah J. Christman and Jonathan Schwartz. Christman’s 7285 is composed from her last several rolls of the titular Kodak Ektachrome stock, discontinued in 2012. Avant-garde cinema has lately been awash with elegies for celluloid, but Christman’s is more interested in exploring the medium’s quotidian character than in fetishizing its look. In rhyming many instances of anticipation (a tennis serve, spring blossoms, landing announcements on a plane, pregnancy, a father’s message on the answering machine) with the final shots of those last rolls being packed up for the lab, Christman focuses our attention on an often overlooked trademark of filming on film: the wait to see what you got. As 7285 so eloquently demonstrates, it is precisely in this lag that small-gauge film imbricates itself into private life. The fine-tuned lyricism of Christman’s cutting was a pleasure in itself, and a welcome contrast after so many films bent on immersion rather than exactness.

Jonathan Schwartz, “A Certain Worry” (2014), 16mm, 3 minutes

Constructed along the lines of haiku, Schwartz’s trio of “miniatures” (a kind of quiet, an aging process, a certain worry) lingers in the mind long after their three minutes are up. a kind of quiet simply gives us skiers and a few hanging notes for piano, heavenly bodies suspended between rising and falling. an aging process sets glimmering shots of boys splashing in a river, blissfully unaware of an encroaching darkness, next to luxuriating peonies. a certain worry cycles through a series of intimations of death and decay glimpsed in the corners of brilliant afternoons. The images appear incidental—quickly framed, underexposed, edited in camera—and yet the tone is precisely pitched between serenity and anxiety. Ripeness means it can’t last, and the moments when you are grazed by mortality are at the heart of life: that’s what Schwartz’s miniatures say to me. They were among the smallest films at Crossroads, and the largest.