1.

“In 1982, Louise Bourgeois became the first woman to be celebrated by a retrospective at the MoMA, and now at the age of 96, is clearly one of the most significant artists, gender notwithstanding, alive today,” wrote Art Observed in 2008, to encouraging readers to go see the major Bourgeois show then at the Guggenheim in New York. A few months later, MOCA in Los Angeles promoted its big Bourgeois show with copy that began,

“This comprehensive exhibition is the first major survey of American artist Louise Bourgeois’s (b. 1911, Paris, France) work in more than a decade. Bourgeois’s long and distinguished career reveals a vast oeuvre in dialogue with most of the major international avant-garde artistic movements of the 20th century—from surrealism to conceptual art—but always remaining distinctively separate, as an inventive forerunner.”

Unmentioned among the “major international avant-garde1 artistic movements of the 20th century,” of which Bourgeois was an inventive forerunner, is feminist art, which would provoke a seismic shift in art discourse starting in the 1970s, a couple of decades into Bourgeois’s career; which established the context in which Bourgeois became the first woman to get a major retrospective at MoMA; and many of the concerns Bourgeois was already exploring in the 1940s.

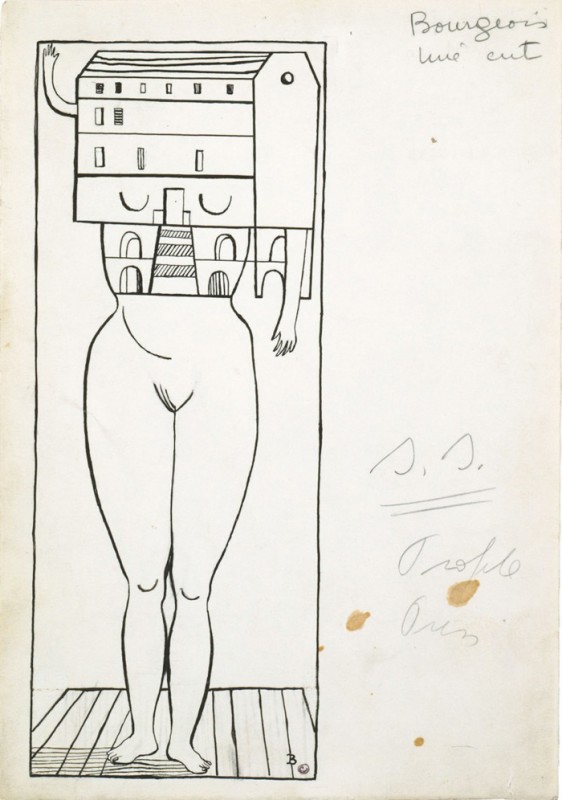

Bourgeois’s paintings and drawings of the late ’40s of naked bodies with houses for heads do of course bear a visual and conceptual relationship to surrealism. That they are women’s bodies under the title Femme-maison (housewoman) struck me immediately upon first viewing them at MOCA as clear evidence of Bourgeois’s feminist concerns, whether in the simple sense that there is a major and obvious gaze and subjectivity shift embedded in the representation of women’s bodies by women in the context of an art history centered around the representation of women’s bodies by male “masters,” or in a more complicated sense. Maybe she was getting into something about the relationship between women’s prescribed intellectual or perceptual purview and their traditional location in the home, and maybe between that and how women’s bodies in western cultures are always/everywhere as if naked, or maybe (sometimes the figure is on all-fours or on her back and there is not just a house but an entire tenement building covering her head) there is something about class or, in that visually new yet emotionally familiar combination of naked hips, thighs, and pussy and un-see-able, surrounded head, something about so-called public and private spheres and just the whole complicated set of questions about female subjectivity and social/structural relationships that Bourgeois seemed to be getting at a few decades ahead of the intrusion of feminist analysis on the art world, and right around the time du Beauvoir would have been writing The Second Sex—but before I had a chance to really think through what might be going on in those images, I was quickly corrected, a little box placed over my head.

Louise Bourgeois, “Femme Maison,” 1947. Courtesy of the internet.

In the 300-plus-page catalogue for the MOCA show, the topic of feminism is addressed in a six-page essay entitled “Is She? Or isn’t She?” that documents Bourgeois’s shifting and fruitfully complicated (and relational) identification with the term “feminist” as well as some of the many feminist concerns in her work, but ends up feeling—because of the title and the minor amount of space it occupies in the book—like a perfunctory nod to “the feminists.” Even more dismissively, the Centre Pompidou assured viewers of the Femme-maison images in its Bourgeois show that year: “More than mere feminist propaganda denouncing the overwhelming burden of the home in a housewife’s life, as the titles might lead us to believe, here we find an immense nucleus of inspiration. The house is the ideal receptacle for all memories and, in particular, those of childhood.” Those apparently un-feminist, universal concerns.

In a 2012 essay called “Feminism in the Man’s Museum,”2 the critic Rebecca Park argues that, though feminist artists are occupying ever more space in major museums, overall the institutions “still don’t know how to deal with” them. Park points to Musée Guimet’s 2011 Rina Banerjee show and the Whitney’s 2011 Sherrie Levine exhibition as examples of shows by artists whose work has clearly feminist content and yet in the institutions’ framing (exhibition catalogues, promotional and wall text, etc.), there is no feminist analysis. About the framing of the Levine show, Park writes,

“[T]he Whitney sidestepped Levine’s sociopolitical commentary to such an extent that it was nearly comical. Take After Courbet (2009) as an example. The work, a gridlike display of eighteen postcards of the same mid-nineteenth-century painting, is approached in the same manner as the entirety of her oeuvre: challenges to notions of originality and reproduction, generally limited to our experience of art and its history. But the composition on display is . . . Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866), an image of a woman’s body so sexualized that it is still able to shock today, nearly 150 years after the fact. If it wasn’t so depressing, the institution’s reluctance to tackle the obvious questions Levine is defying us to consider—how the charged space of women’s sexuality mutates depending on the creator’s gendered gaze, how commercial production exploits and banalizes women’s bodies, how large-scale reproduction confronts and exposes these specific ideas—would be laughable.”

At about the same time, on the other side of the country, LACMA presented In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States. It could have been a perspective-altering show, given surrealism’s overwhelmingly male gaze and abundant use of women’s bodies as symbols. Instead, the exhibition text put forth “feminism” as a straightforward colonial narrative:

“North America represented a place free from European traditions for women Surrealists . . . North America offered [women artists] the opportunity for reinvention and individual expression, a place where they could attain their full potential and independence.”

North America: a free new world for white women to shake off the oppressive traditions of European art history, whimsically plucking and dropping into their work sacred indigenous and Mexican signs and symbols.

Unsurprising, then, that Frida Kahlo’s images—more famous than any of the others’—were the primary marketing tools of the show although most of the artists were white and American or European and, in the overcrowded exhibition, there was no real space or invitation to reflect on the complex content of Kahlo’s work. On a wall of artists’ bios, the photographic portrait of Kahlo was the only one in which the artist was nude. It’s a beautiful image that I have found strong and sexy in many other contexts, but on this wall of portraits of clothed white artists, it told me more about the curatorial and presumed audience gaze than about Frida Kahlo or hers.

Louise Bourgeois photographed with her Fillette by Robert Mapplethorpe in 1982.

2.

When millions of people took to U.S. streets demanding justice for immigrants on May Day 2006, English-language news outlets reported with surprise at the hugeness of this previously “invisible” movement. That they, and most white citizens of this country, had not previously noticed the millions of immigrant workers in their midst who were building toward that moment does not mean that those people or that movement were ever “invisible.” It means that some people did not see them.

That a person who, in Claudia Rankine’s words in Citizen, “has perhaps never seen anyone who is not a reflection of himself” fails to perceive an other does not render the other invisible. It says something, rather, about the one who is doing the gazing—and about the social context in which some people are able to live without ever having “seen anyone who is not a reflection of himself.” (Seeing being a layered verb not limited to physical sight.)

In “The Whitney Biennial for Angry Women,” written in response to the 2014 biennial, Eunsong Kim and Maya Isabella Mackrandilal define “(White)spatiality”:

“There is a specter here that haunts this space. It has multiple faces. We’ll call one white supremacy: the belief in the universal, a pure idea arrived at by a series of white men who have combed through culture and curated its worth. Another face we’ll call visual oppression. We’ll call it passing. We’ll call it presence without provocation. We’ll call it just enough black faces to assuage liberal guilt without the discomfort of challenging anything. We’ll call it the fantasy of postracial America. We’ll call it visible invisibility.”

In their coverage of the current mass movement protesting systemic police violence against Black Americans, many media outlets are addressing the problem of “Why It’s So Hard for Whites to Understand Ferguson” (to borrow a headline from The Atlantic) by reporting on a 2013 study by the Public Religion Research Institute that found that the close social networks—the circle with whom people discuss important matters in their lives—of white Americans are on average 91 percent white. Robert P. Jones, the writer of the Atlantic article and the CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, reflects, “For me, a white man, hearing accounts of how black parents teach their sons to deal with police is difficult to grasp as reality.”

The HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN? collective pulled their work out of the 2014 Whitney Biennial in protest of the inclusion of Joe Scanlan’s Donelle Woolford project, which centers around a fictional black woman artist imagined by Scanlan, a white man.

3.

Twenty minutes into an OK Cupid date with a white guy a few years older than me, he gets onto The New Yorker and casually says he wishes the fiction writers in the magazine with “foreign” names would write more “universal” stories—“like James Baldwin,” he adds, referring to a writer I’d mentioned in my profile. I leave when it’s polite to and still find myself concerned about his feelings when, next day, I decline his invitation for a second date.

(Look at this womanly thing I am doing, bringing in a personal scene when I’m meant to be saying something about public discourse. / I trust you know how absurd it was to have invoked Baldwin like that.)

4.

I think violence stems from, or at least is enabled by, the failure to register another as real. I think love is the opposite of that—it entails seeing another as whole and as real.

5.

Art can and should do a lot of different things. One I’ll mention in the context of this discussion is to find or offer a different way of seeing from the usual or one’s own way. I have doubts about whether simple representation or inclusion have material impact on social systems or people’s lives, especially in the context of neoliberalism, which absorbs and thwarts any real challenge to the dominant order, but when I have some space to hope it does seem that narrative and image and shifts of gaze have crucial potential to increase empathy. Even if compassion and understanding are not systemic change, and even if art has many purposes and it’s arguable whether contributing to human connection or reckoning with reality should be or are among them, representation and shifting (or sharing) subjectivity and communication just might have some role to play in countering actual, daily violence or creating a world less rife with it.

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, 2014. Domino Sugar Factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Courtesy of Creative Time.

6.

Here’s Claudia Rankine on Kara Walker in a recent interview by Lauren Berlant in BOMB.

“In a sense, the scandal of Walker’s A Subtlety . . . is its refusal to contextualize or educate beyond what can be seen. If you can’t or won’t do the math, then the space must hold your reactions too. I struggle with wanting to reroute the content I am living, and often its supremacist frame is pushing back, pushing back hard.”

and

“I sometimes wonder if Walker’s intention is to redirect the black gaze away from the pieces themselves and onto their white consumption?”

7.

There is the persistent problem of what can possibly be received or understood in a neoliberal context in which all subversive or disruptive meaning is assimilated and undermined—a context in which it often feels like nothing means anything anymore. Of what can be received by a viewer whose gaze is circumscribed by the violent construction of its supposed but unreal universality.

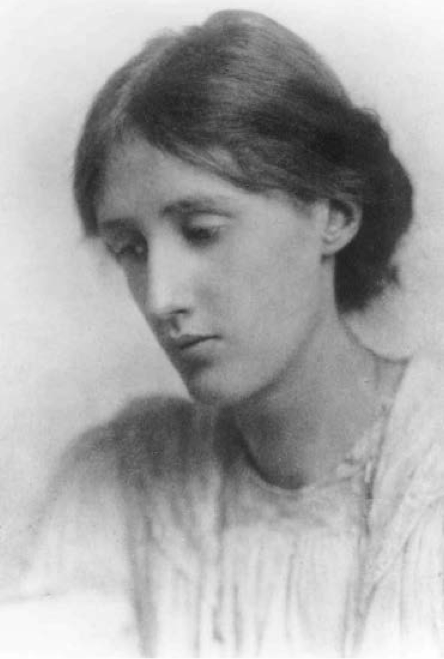

Here’s how canon-keeper Harold Bloom dealt with Virginia Woolf’s feminism: okay, fine, she was a feminist, but only if we define “feminism as the love of reading,” ha ha.

Virginia Woolf, circa 1912.

8.

“A feminist art practice . . . is not a term designating a homogeneous group (i.e., the disenfranchised) or a fixed site (the margin) but rather an agency of intervention—an ongoing activity of pluralizing, destabilizing, baffling any centered discourse. This work, like all feminist activity, is a calculated optimistic gesture.”—Jo Anna Isaak, Feminism and Contemporary Art.

9.

“Outsider art.” Art by the “insane,” the “raw,” the “brute,” the “untrained,” and the “uneducated.”

These are words art-historically (and otherwise) applied to women, Black people, poor people, indigenous people, queer people. These are words culturally close to hysterical, primitive, exotic, wild, unruly, deviant.

The category of “outsider” presumes an “inside” and reifies the colonial/patriarchal canon of properly trained “masters” or elites at the center. Outsider art is art “created outside the boundaries of official culture,” Wikipedia says.

I’m not sure what to make of the fact that the most famous “outsider artists” (e.g., Henry Darger) are white men. White men whose strangeness, whose wildness, whose insanity, whose unpredictability places them in the company of women, people of color, queer people . . .

I don’t know, but I can tell you that Terry Castle, a white lesbian, once described by another white lesbian, Susan Sontag, as “the most expressive, most enlightening literary critic at large today,” aptly titled a fetishizing 2011 article on so-called outsider art in the London Review of Books “Do I Like It?”

After listing a series of “street encounters with lunatics” that she has had (“like most people who live in cities”), Castle goes on to describe her “latest intellectual [and collecting] obsession—the gorgeous, disorienting, sometimes repellent phenomenon known as outsider art . . . best defined as art produced by those, who if not officially classed as ‘insane’ or institutionalised, are in some way mentally or socially estranged from, well . . . the rest of us. Yes, to speak colloquially, I mean the mad—the nutty, the unhinged, the non compos mentis, the permanently unresponsive, the people known, more politely, as having psychological ‘deficits’.”

I mentioned some things about Castle’s identity as reminders of some key insights of feminist thought: women, or gay people, or people of any particular marginalized identity category, are not essentially free of a violent or normalizing gaze; identity is intersectional, meaning that one’s whiteness or class position intersect with one’s experience of gender (for example).

Also to say: feminist content is not inherent in women’s work, and work that is made by someone who does not identify as a feminist might bear fruit under feminist analysis or even expand feminist discourse, and those whose identity has been constructed as normal or universal might see through a feminist or other non-normative lens. Seeing against the grain of normal/universal is not a simple matter of identity. It is sometimes a matter of life experience, sometimes a matter of analysis, sometimes a matter of listening, or looking with openness, to receive something one might not have noticed or thought about before.

Art can be an opening—to fundamental questions about the nature of existence, to new ways of experiencing a thought or a mood, to beauty, to visionary possibilities, to reworkings of a symbolic or other order. Not-seeing the other, whether by consuming the other for their very other-ness, as in Castle’s approach to outsider art, or by erasing other-ness by seeing only what matches one’s own reflection and thereby reifying the “universal” or “normal,” is a foreclosing. That constriction both reflects the limitations of the viewer’s gaze and, cumulatively, affects the social context we are all living in—art, then, both reflects and plays its part in the various violences of an enforced social norm or center.

Steeped in feminist analysis, it is quite clear to me how the idea of “outsider art” relies on a normative center whose borders are policed by identifying slippages of the “universal,” and is connected to discourses that other, exclude, and seek to control women, queer people, people of color, poor people, and people perceived as “having psychological ‘deficits’” in relation to a patriarchal, white-supremacist notion of psychological health and perception of reality. “Outsider art” defines the center while attempting to grasp (or determine whether one “likes”) some peripheral aberration.

10.

These are some things that seem to me to reflect a strange perception of reality:

Joe Scanlan’s Donelle Woolford project. The unimpeded trajectory of Carl Andre’s career after Ana Mendieta fell out of the apartment they shared in the midst of an argument (people gossiped that she was “fiery”, i.e., the crazy one). The celebration of artists who draw racist caricatures as free-speech heroes while Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning are criminalized for disseminating classified information about the violence of the democratic state of which they are citizens. A song that has been played on the radio for decades now in which an American rock star tells an abuse survivor to chill out and open wide for him instead of acting “like a refugee.” News outlets’ preoccupation with the “violence” or lack thereof of a social movement aimed at ending hundreds of years of systematic murders of Black bodies.

11.

While it’s not important to me to claim Louise Bourgeois (or anyone else) for feminism, it feels important to notice the lack of integration of basic feminist analysis (as just one example) in the main stream of art discourse. Incursions are made, conversations are expanded, and still centers are held. I am interested in the ways a normative gaze is maintained in a field that is concerned with looking. The ways the outside or other gets ignored or included or looked at by a non-porous or absorbing gaze. The ways that cannot stop the “invisible” from being there, hanging on the wall, saying the strange thing. The richness that spills outside “universal.”

12.

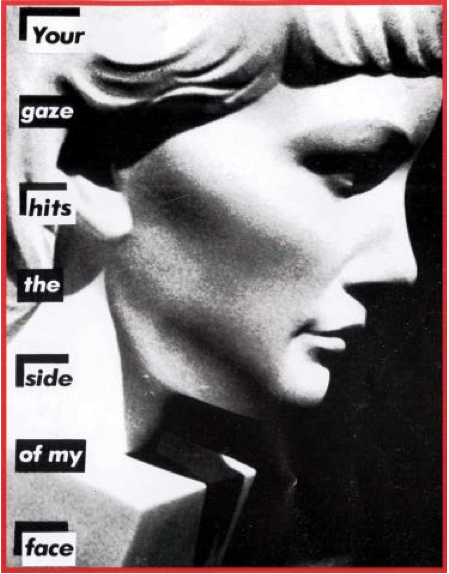

I have no control over what you register.

Barbara Kruger, Your gaze hits the side of my face, 1981.

1) If by avant-garde I can mean what a standard dictionary says it means (“those who create, produce, or apply new, original, or experimental ideas” and “a group [as of writers and artists] that is unorthodox and untraditional in its approach; sometimes: such a group that is extremist, bizarre, or arty and affected”), and not what it has often meant in practice: a group of dudes jerking each other off and announcing how not political their project is.

2) Rebecca Park, “Feminism in the Man’s Museum,” make/shift no. 12