I’m sitting alone in a crowded station waiting to board my next train to carry me across the border from Southern China into Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam. Curious about the sole foreigner in the station, and wanting to practice her English, the young woman next to me strikes up a conversation. Before long, it’s time for me to board and for us to part ways.

“Can you add me on WeChat?” She asks, with a polite shyness, barely masking her excitement when I agree. I’m the only westerner in the station, and I’m slowly growing accustomed to being gawked at and approached by strangers wherever I go. Almost invariably anyone with any English asks to add me on WeChat within a few minutes of talking. She scans my QR code to add me and we go our separate ways. For the next two weeks I get an occasional message from her checking in on my travels.

Many in the West haven’t heard of WeChat, but I bet they will in the next few years. WeChat—or in Pinyin Wēixìn, meaning “micro message”—launched in the start of 2011 and quickly became the largest messaging app in the world. This would come as no surprise if you had been watching Tencent, the company behind WeChat, which is the fourth largest Internet company in the world, after Amazon, Google, and Ebay. In China, a mobile-first country (with well over one billion phones in use), WeChat is experiencing a meteoric rise. If WhatsApp is worth $1 billion, WeChat is immeasurable.

The value, however, of WeChat is not solely in its business plan, which is great, but in the kinds of conversations it allows. The multiplicity of uses allows more authentic and free expression—both political and social. At first glance WeChat doesn’t look as powerful as an outspoken critic on weibo, but access to a platform for millions to have more authentic, open, and ultimately subversive conversations is more powerful than the loudest broadcast medium.

I had been introduced to WeChat a year earlier to stay in touch with international contacts, so I knew how it worked. Yet as I traveled through China the flexibility and ubiquity of the app was striking. I asked everyone who could speak English—which means those more educated and wealthier than average—what the most popular social media app is and why they liked it. WeChat was the top of every list, but the reasoning varied dramatically.

Some used it to talk with their friends. Some more entrepreneurial kids were starting a business on their WeChat, selling makeup and t-shirts with its blogging service and micropayment system. Companies and groups of friends used it for group conversations. I used it with WiFi to call home for free. A few were more outspoken and loved to blog and share their lives with everyone who followed them. While Line, Viber, WhatsApp, and more all have most of these abilities, WeChat is the leader at putting them all together. In short, WeChat’s success rests in how many different functions and audiences it can serve.

In Hong Kong I met with Gabriele de Seta, a Ph.D student at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, who is doing research on digital folklore and media practices in mainland China to talk about Chinese Internet culture and in particular WeChat. When discussing the migration from more public and broadcast platforms like Sina and Tencent weibo, de Seta told me that many users felt that weibo had too much spam, rumors, context collapse, and were subject to the the contentious political nature by both online personalities and crackdowns. Users felt they could better control their audience and be more authentic in smaller groups or one-on-one communication.

During interviews with de Seta about social media use, many people mentioned a feeling that all public-broadcast social media was becoming boring and filled with content that was zhuangbi, which is basically a poser—someone putting on a show to look good. Reflecting on weibo’s decline and WeChat’s subsequent rise, de Seta writes me over email:

“These personal walls and comments are never visible to people outside your friend list, making sharing and commenting relatively closed and ‘safe’ from outbursts of trolling, outrage, denunciations, and even human flesh searches that traditionally originated on more broadcast-type social media.”

Seta’s observations have been echoed in Tricia Wang’s idea of the Elastic Self and Nathan Jurgenson’s Liquid Self, as I mentioned in an earlier article for SFAQ. Real-name and broadcast platforms elicit intense social pressure to perform, a problem compounded in China with government surveillance and a more proscriptive cultural normativity. In Wang’s talk at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, Wang said that, “Access to the Internet enabled them [networked youth] to discover and express themselves in ways that were not possible offline.”

Wang points out that the Maoist regime broke personal trust through a dictatorship fed on informants. While this is no longer in practice to such an extent, the ramifications are still present in contemporary China, both online and off. But Wang isn’t only referring to government surveillance as a barrier to fuller self-expression. Indeed, de Seta and Wang both stress the strict social expectations placed on Chinese youth in the family, their community, and by their peers. Constant public messaging caused a great pressure to perform in a specific, less authentic manner. While many users de Seta encountered had multiple weibo accounts for different messaging, WeChat made this desire much easier.

Government surveillance is considered nearly omniscient in an unencrypted Chinese Internet, but nobody seems to mind unless they’re engaging in conversations or plans to organize against the State. Everyone I spoke with during my month in China knew that there were things they could not say, but rarely seemed bothered by such limitations. The web, and especially WeChat, has allowed these networked youths to have more social freedom than their parents and communities had previously allowed—so what if they can’t organize a revolution? This went against my strong commitment to free speech, but was echoed in Seta’s and Wang’s work and by everyone I spoke with.

One exciting way this new freedom of expression has been most obviously seen is through memes. As I wrote for VICE, despite many in the West believing the Chinese web to be a surveilled black hole, I’ve found just the opposite to be true. The Chinese web is a vibrant and active space, full of puns, inside-jokes, and ever-evolving memes that migrate across many social platforms largely unheard of in the West.

Mandarin allows for fun wordplay in a way English does not. Simple shifts in tone and slight variations in written characters can make dramatic differences in meaning only noticeable by creative and fluent speakers. This, coupled with vast variations between local dialects at times only represented in oral communication, makes the audio messaging function even more powerful for native Chinese speakers.

However, many Chinese netizens are using WeChat not for precise and nuanced local dialects but for creative play with the national language. Most infamously is Grass Mud Horse, said cao ni ma in Mandarin, which, with a subtle tonal shift, becomes an expletive against a person’s mother. In this case, “mother” falls under Chinese censorship, and the overt political nature of the meme is likely what made the Grass Mud Horse the most popular Chinese meme in the West.

Memes are everywhere on the Chinese web, but few are as political as the Grass Mud Horse. Much like the West, most of the memes are childish, funny one-liners, and reaction GIFs. Messaging apps in Asia, the first being Line in Japan, wisely recognized this trend, and made stickers—little animated pictures akin to emojis—to be used in messages. WeChat went further and allowed users to upload their own stickers and GIFs, letting conversations take on a new form of visual and creative dialogue.

While many rural kids I met in China loved using emojis and stickers on WeChat, many of the more networked urban youth used these animations at a dizzying rate. Conversations became a flow of inside jokes, emojis (usually in multiples), animated reaction gifs, and stickers all complementing and flowing around the words. Some I recognized, but many I had never seen and could no more decipher alone than hieroglyphics.

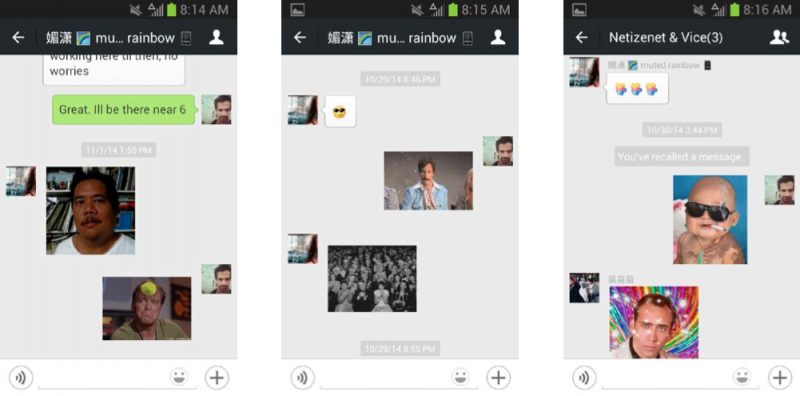

Examples of my meme and GIF filled conversations on WeChat while in China. Courtesy of Ben Valentine.

The two things that most caught my attention were the amount of porn passed between users (which is largely censored from public web content in China), and the use of Chinese politicians in memes. While I didn’t find many that were overtly political, the very act of animating Chairman Mao’s face to make an awkward smiling GIF was startling. As was repeated over and over to me, almost everything is allowed online, unless it’s organizing against the State. So while State television is still heavily censored and cleaned, social media platforms like WeChat allow for very different conversations.

Wang believes the freedom to explore yourself in anonymous online spaces can facilitate more authentic expressions of self and stronger social bonds. During her research Wang found that eventually, albeit in a very small portion of the population, these bonds can lead to deeper civic engagement. However, this notion is heavily debated, especially as China has ramped up censorship, instated real-name policies akin to Facebook’s but for the entire web, and other more punitive Internet policies.

Jason Q. Ng, a research fellow at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab and author of Blocked on Weibo, writes “coded language may offer its users a feeling of valiantly fighting the system when they are merely shouting into the void—or, at best, speaking to an inner circle that already shares their views.” Chinese censorship has a powerful grip on social media, which has recently expanded to ban political wordplay.

An Xiao Mina, co-founder of The Civic Beat (where I also work), has written that we must understand how positive and open expression, online or off, can be understood as internally liberating, even while looking insignificant in the face of systemic oppression. Mina believes that these “micro-affirmations” have become “a key part of building solidarity. The work of social change can start with the tiny changes in our hearts and minds.” State-controlled TV and newspapers don’t have many micro-affirmations, but WeChat is full of them.

This gets to an idea I’ll call a micro-protest, a tiny affront to a cultural norm or law, often at the level of the individual or in communication among a small group.

The micro-protest is a change in how something is discussed; to make a taboo subject become socially acceptable, laughed at, or less serious. While a protest demands a new law, or that society change, the micro-protest sets or demands a new expectation of interaction if only within a small group of people.

Unlike mass media, broadcast social media, and often real-name social media like Facebook, WeChat allows for micro-protests to easily form. While I don’t believe that the micro-protest will necessarily make a net-positive change, without the freedom to communicate in an authentic way where this type of micro-protest is allowed, the opportunities for people-led change remain slim.

I do believe WeChat (and the web in general) is building an ecosystem that could unlock the power of the general public. What we choose to do with that ability remains unclear and is likely reliant on even larger systems such as education and economics. Micro-affirmations and protests, privacy (at least to your general community if not the State), and more free expression and creativity—these are invaluable. These wild animated GIFs, shared in private with strangers or our closest friends, allow us to more fully explore ourselves.