Jesús Rafael Soto

Chronochrome

Galerie Perrotin

76 rue de Turenne, Paris 75003 & 909 Madison Avenue, NY 10021

January 15 – February 21 (New York)

January 10 – February 28 (Paris

Le cinétisme, ce n’est pas “ce qui bouge,”

c’est la prise de conscience de l’instabilité du réel.

– Jean Clay[1]

That Chronochrome, an exhibition of works by Venezuelan artist Jesús Rafael Soto, occured simultaneously at Galerie Perrotin’s Paris and New York locations was a delightfully meta realization of the artist’s aim to transcend time and space. Chronochrome, curated by French art historian Matthieu Poirier, presented over fifty works created by Soto between 1957 and 2003. Recognized in his lifetime as a pioneer in the landscape of modern art, curators and scholars are now beginning to revisit Soto’s posthumous impact on the history of art — an international trend that is illustrated by the artist’s prominent feature in solo and group shows throughout Europe and North America.[2]

Interdisciplinary in methodology and approach, Soto understood art not as a form of expression, but the manifestation of knowledge. He believed that artists were responsible for exposing the public to contemporary scientific research, and through his work, aimed to depict the phenomenological reality of the universe. With a simple abstract-geometrical vocabulary, Soto developed an innovative artistic language with which he articulated immaterial elements and sensible states. Time, space, movement, and energy become perceptible values through dynamic, pulsating compositions that engage viewers in an interactive exchange.

Chronochrome was presented as a panorama of Soto’s artistic career. Conceptually, it was conceived as a transatlantic aggregate; regrettably, however, most viewers could only experience half of the two-part show—an inevitability that was seemingly unaddressed at its curatorial inception. Almost two-thirds of the exhibition resided in Paris, leaving its New York counterpart anemic in comparison. Most notably absent from the latter were Soto’s Penetrables — immersive environmental installations which arguably constitute the artist’s most significant body of work. Chronochrome’s Parisian manifestation (my experience of which was limited to a printed leaflet) appeared successful in presenting a survey of Soto’s oeuvre. Though the same cannot be said for its Stateside Doppelgänger, lacking in examples from several bodies of work, Chronochrome was nevertheless effective in demonstrating to its New York audience the vibratory sensitivity that served as a hallmark for Soto’s art.

Pénétrable BBL bleu, 1999, Edition Avila (Succession Soto) 2007, PVC, metal, 12 x 46 x 15.4 ft. (365 x 1400 x 470 cm). © Jesús Rafael Soto/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, 2015/Galerie Perrotin/Livia Saavedra (photo)

New York’s pièce de résistance was Progresión elíptica rosa y blanca (1974). In this free-standing sculpture, thin metal rods of varying height vertically emerge from a rectangular white base. Shorter rods in the foreground are painted white, while taller rods in the background are painted white on the bottom, mirroring their anterior counterparts before eclipsing them in pink. The color gradient and undulating dimensions of this work are reminiscent of an aurora. As one moves around the sculpture, its isolated formal elements interact optically—an ethereal mass coalesces and dissolves. Volume no longer occupies space, but acquires a temporal value as it appears and vanishes at the mercy of the viewer’s vantage. With Progresión, Soto illustrates the subatomic plasticity of matter, itself destabilized and reduced to quantum vibrations.

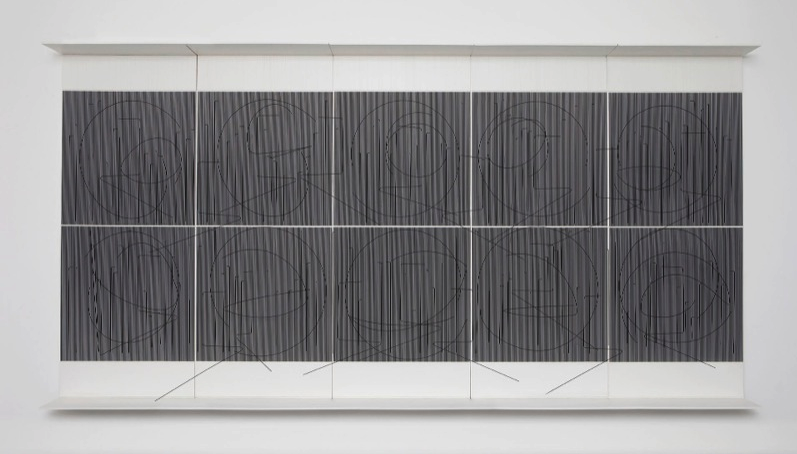

An honorable mention goes to the spatial drawing Ecriture (Ecriture noire) (1982)—thin black wire manipulated into different geometrical shapes and lines which Soto referred to as texts, are suspended by translucent nylon threads in front of moiré wooden panels, painted in high-frequency black-and-white lines. The effect is a three-dimensional drawing of sorts in which the physically-detached foreground fuses, fades, and reappears against a pulsating background, presenting phantasmagorical compositions that gradually unfold in real time and space relative to one’s position. Never revealing itself in its entirety, Ecriture exists in a permanent state of flux: its forms dematerialize and oscillate in a transitory state.

Jesús Rafael Soto. “Ecriture (Ecriture noire),” 1982, paint on wood and metal, nylon, unique. Courtesy Galerie Perrotin.

Chronochrome’s occupancy in Galerie Perrotin’s Madison Avenue space was harmonious overall, if somewhat austere in its lack of sculpture. The show’s chronology was a-linear, instead privileging an arrangement that presented various bodies of work together. This was appropriate, aesthetically and intellectually, as Soto himself did not embark upon a strictly consecutive development: though a progressive conceptual and representational evolution identifiably exists, Soto utilized various methods and means of expression intermittently throughout his career. The artist explains:

I have never been afraid to re-approach problems that could be improved or that I left unfinished {…} This is because I conceive art as a set of questions that must be solved by the artist, because they are problems posed by the age he lives in and not because he feels like doing it. The history of art takes you down that path, and you become a creator insofar as you find solutions to these questions. Artists in general are concerned about doing something personal and original, whereas I have always thought that, to the contrary, it is about something else: taking on the history of art and pushing it forward a little, taking a supplementary step within the issues it poses.[3]

Led by the accomplishments of Mondrian and Malevich with their two-dimensional suggestions of space and movement, Soto drove his own work into the fourth dimension. To achieve this, he understood it was necessary to integrate time:

Space, energy, time and movement are universal entities that affect us all. My notions of relationships are determined by the behavior of these inseparable entities. This idea has always influenced my work. In a nutshell, a relationship is a force, a universal behavior; it’s a kind of infinite elasticity which gives rise to all transformable values…We live in a space entirely filled with relationships…these relationships also necessarily imply movement. Movement cannot be considered as separate from space and time.[4]

Through the repetition of formal elements and multilateral perceptibility, Soto heightened the distribution of movement. This means that the viewer becomes an integral part of the work, the essence of which is only realized in conjunction with his or her shifting position. Thus, the artist established a symbiotic relationship between art and viewer as the latter becomes a vehicle in constituting the former. In collapsing the distinction between art and humanity, Soto conceived an entirely new human experience that reached a crescendo in his microcosmic Penetrables. Therein lies Soto’s most significant contribution to the consciousness of contemporary art—in the scientific rigor of his praxis, Soto shifts our tactile awareness of space from the area before us to the area enveloping us: “I believe that Man is not facing the universe, but that he is inside the universe…the one who continues to see the universe as something outside himself lives his life as a spectator. But we are not spectators, we are participants!”[5] In New York, Chronochrome demonstrated this concept intellectually, but fell short of doing so tangibly.

—

[1] “Kineticism is not about “things that move,” it is the awareness of the instability of the real.” -Jean Clay, “La Peinture est finie” (Painting is Finished), Robho, no. 1, 1967

[2] Recent solo shows include: Pénétrable de Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, (October 6, 2014-March 15, 2015); Jesus Rafael Soto: Houston Penetrable, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, (May 8-September 1, 2014); Soto dans la collection du Musée National d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris (February 27-May 20, 2013); Soto: Paris and Beyond, 1950-1970, Grey Art Gallery, New York (January 10-March 31, 2012). Recent group shows include: ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s-60s, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (October 10, 2014-January 7, 2015; forthcoming at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam and Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin); Radical Geometry: Modern Art of South America from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection, Royal Academy of Arts, London (July 5-September 28, 2014); Dynamo. A Century of Light and Motion in Art. 1913-2013, Grand Palais, Paris (April 10-July 22, 2013).

[3] Ariel Jiménez, Jesús Rafael Soto in Conversation with / en conversación con Ariel Jiménez (Caracas: Fundación Cisneros, 2012), 94.

[4] Matthieu Poirier, Soto (Paris: Galerie Perrotin, 2015), 174.

[5] Poirier, Soto, 168.