Well, Charles, here we go. We’ve known one another pretty well for quite a while.

For almost 20 years, going back to around ’94 when your Stanford buddy, Michael Moore, had a show at Refusalon on Natoma Street.

It’s a long time that we’ve interacted in the local art world—we agreed that our theme is being an artist in San Francisco and what that means. The term I would use to introduce you and your artistic identity is conceptualism. We’ll talk about that. But to start out, why don’t you begin with the early events and people in your life that were influential in shaping who and what you have become as man and artist.

I was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1967 and really grew up in the south, primarily in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, until I was a teenager. I finished high school and moved to California in ’85, to Los Angeles. I spent a few years there working, going to school—and loving life in LA at the time.

Do you remember when you first became interested in art?

My mom and dad met at art school in Pittsburg. So I think I’m their biological sculpture—and apparently that’s about all they have to show for art school.

Did they encourage you?

I feel really lucky in that. We still look at art together. They helped push me to where I am—specifically my mom.

Do you remember when you first became aware of art as something other than illustrations in magazines?

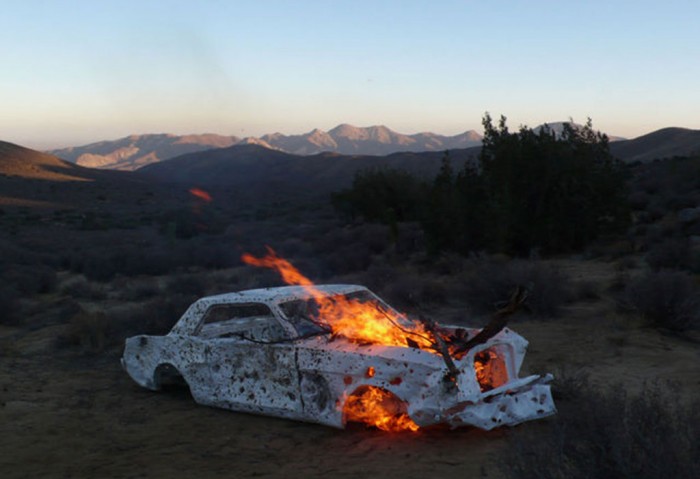

Yes, I do. Mom was a good representational painter who trained me how to paint like John Singer Sargent—or, at least I thought I could. But my mom was far better at it than I ever was. In fact, that created kind of a schism between what I thought was art and what she was doing. One of the first art things I remember took place when I was only 15. We used to camp out in this old grain silo along the railroad tracks with oval windows all the way up the side. One afternoon we lit a fire and then backed up about 100 yards and took a photo at sunset. It was this internally lit cement silo, a beautiful image—I realized where my work was headed, towards ephemeral events. I look back on that as one of the first real pieces of art that I made. My friend that camped with me that night, she and I realized it was a great fleeting moment. We got that one picture to take away from the event, and sometimes that’s all you have.

Go west, young man. Somehow you got that message. As did earlier Southern Tier artists such as Ed Ruscha—who famously chose LA. Why for you the allure of Los Angeles rather than San Francisco?

My brother moved there after college, and we both wanted to start a new life. I knew I had to leave Alabama. It’s hard to describe why, but I just knew that I couldn’t get what I needed. I couldn’t become what I was trying to become at that time. One of the first things that I did when I moved to Los Angeles was work in a machine shop. I lived in the back of the shop for two and a half months before I found a place, and it was an incredible welcome to what LA really was—this international community of people working, pursuing hybrid dreams. I lived with a handful of illegal workers who were doing just about anything they could to create a new life for themselves. Most of them were from Mexico and Central America. For me, as an 18-year-old, it was about pursuing a life of exploration and adventure. That was what art was to me and I think still is. Moving to LA was the adventure of the unknown, of the west. That was a great time—the three years before I moved to San Francisco set the tone for my art making in California.

That was 1985, correct? And there was quite an active art scene. You haven’t said anything that suggests you knew what was special about LA or San Francisco—either one. Is that true?

Well, I’ve got to admit to being largely naïve about what LA held in the arts. At that time I didn’t think I was pursuing any kind of art career. I thought I was becoming an artist, but I can’t even say that I knew much about contemporary art at that time. I remember seeing a show at L.A. Louver that was a stunner: a whole environment by Ed Kienholz that was like an old bar that you could walk through, that really impacted me. Seeing the scale of shows that were being put on in Los Angeles impacted me, too.

Would you say your real art education began in Los Angeles?

Yeah. I was shunning what I thought was painting—representational art, the making of objects presumably for sale or on commission—for a life of unpaid experimentation and adventure. And that’s what I think I’ve done essentially ever since. After moving north I found what I had perceived the San Francisco scene to be. The undeniable freedom from the sixties, the sense that anything is possible— Tom being one of the first persons I bumped into. That cult of individuality.

Tom Marioni?

Tom Marioni. And then performative rituals that created a kind of conceptual art cult here, if you will. Those were influences on some of the things I did when I first moved here. I think what I’ve done is different than what those predecessors did, but no doubt influenced by them. Some of the first works were Refusalon and the gallery projects through the nineties.

But you talk about this process of becoming an artist, especially the LA time, and the influence of the poets and what you admired about them. And that seems to me a romantic notion of living the art life, of being an artist, which often appears to be mostly self-focused.

I think ultimately art is the most indulgent personal activity one can possibly pursue—really. Does it cross the gap to communicate with people? I don’t know. I admit to being readily absorbed in my personal pursuits. I think occasionally people get my work. I like to think I’m holding up a mirror, but I realize it’s a very narcissistic pursuit. I get better at trying to be on the outside of the bubble so that in a way you’re looking in. But you’re also able to look outside the bubble. That’s what I would hope is my basic position as an artist.

Holding an Anna’s, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery 16, San Francisco.

I’m a little puzzled by a position that is so self-absorbed and insular but takes place within a community that tends to be self-congratulatory. Does it get to that point where if you live the art life, no matter what you make or what you do, it’s really all about yourself and your friends?

In that respect, I would have to respond again that it is a private activity. I tried to do a gallery for years and really enjoyed that public activity, but now I’m in a position where I feel like my work is very private. I like working from that position rather than having my doors open to an ostensible public that didn’t get what I was trying to offer anyway. And so I feel like now I can select my audience more. I think the breakthrough comes when you meet that occasional individual who gets the big picture and realizes it isn’t just about a single painting on the wall or one you might be working on that day—being able to give a walk-through of the studio where somebody really gets the big picture of lifestyle and art. I feel great if I can be a conduit, reaching out to others who live similarly or who see art similarly.

Well, I know you get that kind of feedback, which suggests you’re successful.

Success. I don’t know what that is. I certainly couldn’t claim to have had much commercial success. I think success is happiness and whether or not it’s working for you in the big picture. I’ve got a system that works for me, and I think that the product is trying to stay happy, trying to stay positive about what I’m doing. That’s the work, and I think I’ve got to keep it positive to keep doing it. It’s not always easy. But I would agree I make art for myself—100 percent. I don’t do this for the market. I don’t do it for girlfriends.

When I say success, I mean successful in terms of communicating. You’re a social person, and art is a way of communicating. Most of the artists I know who really are serious about their art—that’s important to them.

I know I reach them, but I’m not preoccupied with it. I think there are people out there who get my work. I don’t claim to do it for them, by any means. That would be really narcissistic. But I think admitting that I do it for myself is an honest beginning. When people tell me they get it, I feel like that’s a great sense of acknowledgment. I don’t do it for them. But it’s sometimes heartening to know that people do like the look, like the feel, or get the pathos of the project, if you will. In Mudslinger, for instance— which was like an adventure handbook of my life in a funny way, a recent art book I did for my Tijuana show—I felt really good about that piece, but it was a reflection of my travels and times and the ephemera of my work.

But you say that you don’t particularly care. Making things is the source of happiness—this, again, I guess is one way to look at an activity. But on the other hand, I know enough about you to say that you are pretty disappointed when people don’t seem to be paying attention or making the effort to understand you.

I guess that’s true. I mean, one can’t derive support entirely from no echo. I think of one artist, an Israeli artist I worked with who spent time in the Bay Area, who after his show came back to me and said, “Charles, I just don’t feel like there was any echo here in the Bay Area.” And I’ve heard that from many artists, especially ones not from here. And I wonder if that is a plague on our scene and our work. You mentioned the possibility that I’m just talking to myself—is it all just about me? I think the Mudslinger book was a good example of collaborative art making because Griff Williams gave me some ribbing in a way, not unlike what you’re doing. He said, “Hey, who does this reach, or who are you trying to talk to with this?” One of the images in the book was the lid from a soda cup with two straws in it. It’s in the middle of the book. Griff just goes, “What the hell is this, what’s going on with this? You’ve got to tell me about this.”

Remember, people have to bother to try to understand you. They have to think it’s worthwhile. And many artists say, “Oh, well, the work takes care of that.” Isn’t that something of a modernist romantic notion?

The book is really all about relationships, and specifically my relationship with adventure, sometimes involving girlfriends. There are a number of friends in the book. So the relationship between word, image, and the overall feel that comes from their combination, I think that’s what we tried to wrench out in that book. Something about relationships and how the image reaches its intended audience or . . .

Well, what is its intended audience? An intended audience presupposes caring about being understood, having you and your work—and their relationship—understood. Even appreciated. What about Tijuana?

I was humbled to do the show there. When you’re offered a show you want to produce something for the audience that represents you but from a position that offers an access point. I felt like I did that for the TJ show. It came from many visits there trying to figure out who the audience was, the people that would see it, and whittling away at the elements in the story to include only what was necessary. That was tough.

How did you make that decision? Select what was necessary for Tijuana?

Well, the main piece was the bullet-riddled car, the Ghostang sculpture, which has gone on many different voyages and seen many different moments and events. The piece had been in Tijuana for a couple years—that was the main way that I was known in Tijuana, as the guy of the Ghostang. And we tried to use Ghostang, as a point of departure throughout the book Mudslinger as a kind of touchstone or hallmark over the years in my work—and a way to approach Tijuana as a border culture. I don’t know how successful it was, but the two night events were great, and I felt like the people that showed up did get it.

What happened in these events?

It came out of this pig roast obsession of mine. My host there, Luis Ituarte, said, “Hey, I saw the video, why don’t you do one of those here?” I thought this was great and it gave me a chance to invite my chef collaborator to come down from Oakland, and then also a band that showed up. So it ended up being a multi-ring affair. It wasn’t just my work. It was a community event ultimately. Being able to serve them wild boar tacos in Tijuana was just nothing short of . . . Anyway, I came back from Tijuana with an incredible respect for that culture.

Sounder of wild pigs at Las Viboras, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and the Sparling Family.

Well, maybe that’s one reason to do it.

In fact, it really was. It was to embrace that whole appreciation of bubbles that I think is what my work really is. I saw Luis’s own passion and obsession with his pet project, his gallery, La Casa del Tunel, a redeemed smuggler’s house. I just really identified with it and thought, man, I want to seek this guy out, go down there, find out what the scene is about, and I just became really obsessed. I felt maybe a little tired of my local scene, and what it forced me to do is to look elsewhere for inspiration. Community is where the connection comes from, and that’s when you realize you’re not just participating in a regional circle jerk. That’s when it really gets interesting. Your new audience gets your work and the bubbles overlap—a kind of catalytic reaction. That’s what was great about meeting Luis and being there.

It sounds as if you two became good friends in a short period of time. But let’s now go back to San Francisco and the Art Institute.

Well, I ended up getting this scholarship to come here. I perceived the Art Institute to be a vehicle for why I came to California. I look back on it really fondly. I think of it as a little cauldron. One of my teachers, Tony Labat, used to love to turn up the heat on us to watch us squirm. Tony was a really great influence on me at school. He’s there to push you outside the boundaries—to provoke, inspire, challenge. One of the things that stuck with me from the years I spent there with Tony was how he would point out to us that maybe one out of 20 in the group would go on to do something that might get written about or might get put in a newspaper or might get bought by a museum. And I remember it created a bit of a culture of insecurity.

But I remember specifically thinking, “I am going to be one of that 10 percent or less, I’m going to be one of those people.” And in that regard, I thank Tony . . . the one individual there who really pushed me. He was constantly fighting to define a position unknown at the time. I think that’s what I always really thought art was about, pushing you towards this lifestyle of experimentation and discovery. I found Tony very inspirational in that way.

You were at the Art Institute from 1988 to 1990. Right?

Shortly thereafter I was faced with the predicament of being a young artist—of how to get my work out there, how to take my essentially private activity into the real world. There was a perceived guild system with which this supposedly operated, but from what I could tell it was all based on nepotism and insider trading. I realized it wasn’t going to happen unless I started my own entity. Refusalon was a vehicle for my colleagues and me to show what we thought art was, a framework for creating an audience. That was our solution to being art students no one had ever heard of. We were faced with how to get people to look at the work and maybe write about it, get affirmation enough to keep doing it. That for me was about a nine-year-long project that was essentially non-commercial.

What year did you open your doors?

Refusalon started in 1990, in January 1990.

Now, does that include Natoma?

Yeah, the Natoma era really was the beginning. Then we took Refusalon out of the South of Market “wine country”—as we used to call the neighborhood—and moved to Hawthorne Lane next to SFMOMA: our attempt at going commercial or at least integrating market concerns with our otherwise ephemeral lifestyles. I kept with it until ’99 when I essentially turned over the reins to my then co-conspirator, Shmulik Krampf, and he took over the project, bringing to it his own idea of what it was as a temporal, conceptual work. I said, “Hey, I see this as a gift. You’ve got to maintain it, bring new wrapping to it—you have to fervently present it in the tradition that I’ve created.”

In a short time we’ve moved to you starting Refusalon—with which in the minds of many you are still associated. I’m still not sure if the Natoma venue was proto-Refusalon or its first iteration.

I feel like the heart of the matter happened in the earlier days on Natoma. That was what Refusalon really was. Once we tried to change that and take it downtown and commercialize it, it wasn’t the same anymore. The idealist in me maybe fetishizes some of the earlier projects and really ephemeral events.

For example, one night at a performance event on Natoma Street, perhaps one of the most memorable nights ever at Refusalon—and I know Tony, my old teacher, would say this was the only thing that Refusalon was memorable for—we all were out in the backyard watching the performer when out of nowhere this guy comes walking into the backyard and simply sits down right in the middle of this campfire. Before anyone can realize what’s happening, he’s caught on fire. The other guy’s performance, no one even remembers to this day. This guy is seriously injured. You can see that he’s got a grizzly burn on his ass and leg; his pants are burned off. I’ll never forget, I walked out the back door just as this happened. I run down the stairs and we drag him out of the fire. I remember thinking, “Oh, my God, we’ve really gone too far. I needed to set some limits here.”

Was he a student of Tony Labat?

He was another student of Tony’s.

Let’s talk about Tony. Obviously he was inspirational for you. He was within what appears to be a protected school framework where the school’s noninterference policy has been to let the teachers do whatever they want. Apparently Bruce Conner famously took advantage of that freedom. Or so I’ve been told.

Well, I’ve heard the stories, too. I know exactly which ones you’re talking about. With respect to Tony though, there were just different styles of doing things. For instance, George Kuchar would pick the star students and nudge them on to do whatever they wanted, but then he’d take credit for it. Tony had a similar but more provocative way of going about it. At the time it was tough for me. Now I think that’s the role of the mentor, of the teacher—to provoke. It is to ask you to consider if the pre-existing model is good enough for you anymore. Are you going to have to fucking destroy it, break it down, rebuild it, and then call it something different? Tony encouraged us to create our own individual art worlds, if you will, whatever the cost. Yeah, I think that was inspirational, and it created a competitive environment amongst the students.

What I took away from Harold Bloom’s book The Anxiety of Influence (1973) had to do with art school and the whole idea of the others that have come before: what they did and their influence on you creating anxiety. I remember thinking of that in Tony’s class—who went hard on us for knowing our antecedents. It wasn’t so much that somebody had already done something, but a lot of people operate in naiveté and don’t realize that there have been influences that have impacted their work. There was a whole student subculture that was paranoid about doing art for fear that it had already been done. I just thought that was such a paralyzed position to operate from.

As you say, you look at least foolish—if not stupid—if you think that it all started with you and that your work is somehow . . . uniquely original.

I think it touches on what is a culture of privilege, a culture of elitism that art precipitates—and I embrace that. I do believe it’s a very personal, selfish path. And I think what I got from Tony, Wally Hedrick, Jason Rhoades—or the tradition of the Art Institute—was kind of a culture of truth, seeking the individual path at the expense of everything else . . . I look back on that time at SFAI as one of the richest of my life, just in terms of experimenting and meeting other artists, the youthful embracing of this ephemeral little scene we had. I think that’s what it was really all about—that tradition of the Art Institute. The calling card has perhaps little other value, but it’s an elitist cult that those who have been there really identify with and are proud to be part of. I know I am.

You mentioned “truths” several times, and I think it’s fair to examine the words we use—you know, the judgment that art is or isn’t true in a “culture of truth.” What does that mean in the art context?

It just speaks again to whether or not I should have moved to Los Angeles after graduate school like, say, Mark Grotjahn, whose paintings now sell for over a million dollars. Did I do the wrong thing in staying here? I don’t think I did. It was a lifestyle choice. But that came at the expense of perhaps selling paintings. Was it worth it? Yes. I guess for me, the pursuit of truth is in knowing and sticking with the path versus being distracted by the temptation of a career, maybe a teaching job, maybe a stable job at the post office. The truth was sticking with the path. There isn’t any marked path to follow, to find your way. You have to make it all up. When you start working in some revisionist way it’s usually pretty evident, and you think, “Oh, I don’t want to do that because so-and-so may have already done that.” That pushes you to stay on the quest for your own unique vision. Maybe that’s what I mean by truth— to avoid cliché or stating the known.

During our conversation, I’ve been thinking of Dada and the idea of tearing down, pushing boundaries, and that there’s merit in that goal. But do you feel that the Art Institute—maybe aspects of the San Francisco art community, but especially the Art Institute—valorized transgression, perhaps for its own sake?

Undoubtedly. Beyond the sensational. But I found later in my career that I seriously needed some limits. Limitations are bad but you need boundaries within which your art is contained. I think setting those as an individual artist is tricky. How do you integrate yourself into an existing system that promotes art? Or how do you create an entire system that promotes what you think art is? That was the challenge.

Well, in fact, what I feel you’re touching on—the kind of truth you’re bringing up— is that the better art comes from collaborating. I’m so bored with monomaniacal artists, that one person doing the same thing over and over again. I need others to tell me what’s not working, and what stays in. I think that can help you better reach your audience. That’s where dialogue and having an art community really inform you and make the work what it is.

Some of the leading visual artists either didn’t go to art school or dropped out. Then why go to art school? What do you get—and then maybe don’t get? Because in the age of conceptualism, you’re no longer primarily learning craft—method, materials, technique.

That’s a good question. I guess it goes back to that thing we’ve talked about several times. We were ostensibly operating in what was perceived as a guild system. One thought that this would lead to being integrated into gallery shows, purchased by museums, written about by magazines, collected avidly by supposed art collectors. In fact, what you’re buying into is an elitist system of insider trading. What the schools and galleries are trying to do is commodify once-radical personal narratives by converting them into salient, long-term art market investments.

And you pointed out that the Art Institute at one time took pride in being the only true fine art school in the country—meaning without a commercial program—without that practical side.

Or perhaps even more memorably, without graduates matriculating into the art world, which I think was really the problem of the Art Institute for a while.

How do you mean?

It’s like an elite cult of artists that you’re part of. Whether or not the art school education amounted to anything, the ones who are still out there on the street doing art and getting shows and making books—it’s interesting to be part of that. I think of the Studio 13 jazz band as a metaphor for the Art Institute, or how I envisioned myself fitting in. These idealists chasing truth, in pursuit of pure art at the expense of a career. As younger artists you look at the older artists and watch their demeanor. You try to determine whether they’re comfortable with this, do they really believe this? I remember particularly Wally and Richard Shaw, who both were teacher figures of mine. Shaw was a teacher of mine at Berkeley later. Wally was more like a mentor figure. But they were living it. They were really doing it on their terms.

Another example might be Emerson Woelffer at Chouinard in the 1960s. Many of the younger LA artists—Ed Ruscha, Joe Goode, the Ferus people—looked up to him. Not necessarily for his work but for his example: “He showed us what it was to be an artist.”

That’s an interesting way of putting it. I think what I took away from Richard and Wally was that both seemed content genuinely pursuing their careers. I remember Richard having a real sense of humility and being a great teacher, being able to talk about your work and never bringing himself into it. I think that’s the measure of a good teacher. True, sometimes they’re talking about themselves, but they’re able to make you divorce yourself from the material. If you can divorce yourself from your agenda and be comfortable in that, it radiates—its power communicates almost without you. I remember thinking that’s what was inspirational about Wally. His was a body of work whose infamy preceded it—yet it didn’t add up to a commercial entity. What was inspirational was his commitment to this extremely personal body of work.

Well, perhaps that’s the truth-in-art we’ve been looking for.

Aun Aprendo, 2014. Neon sculpture. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery 16, San Francisco.

www.charleslinder.com // Instagram @linderisms // Twitter @charleslindersf