Whorled Explorations

Kochi-Muziris Biennale

India

December 12, 2014-March 29, 2015

Visit Pepper House in Kochi, India, these days and, in its central courtyard, you will encounter the arresting sculpture of a wiry primate. It stands over eight feet tall, holds a globe in one arm, the other pointing heavenward, and bears the gaze of a knowing sage. Entitled Matter, 2014, by N S Harsha, it is presented as part of India’s ongoing biannual art event, and is emblematic of the audacious spirit of the Biennale itself, with feet firmly rooted on the ground, sights set high.

Pepper House Courtyard. Photo by Colin Fernandes

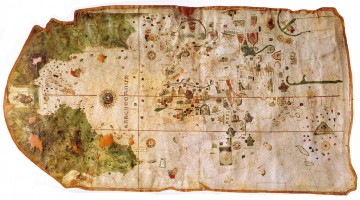

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale, now in its second iteration, is the actualized dream of contemporary Indian artists Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu. Held in the seaside town of Kochi (formerly known as Cochin) in the southern Indian state of Kerala, the biennale is also named after the ancient trading port of Muziris (believed to have been located in the neighboring Periyar Delta). The twin ports of Kochi-Muziris bear a complex cosmopolitan and colonial legacy with traces of Arab, Chinese, Jewish, British, Dutch, and Portuguese influences. This regional history of transition and assimilation is layered anew as the art world now descends on Kochi’s welcoming shores.

The current edition of the Biennale, cleverly titled Whorled Explorations, opened December 12, 2014 and runs through March 29, 2015. It features ninety artists from twenty-eight countries exhibiting at heritage sites all over Kochi. Aspinwall House, a sea-facing trading complex built in 1876, is a principal venue and houses works by sixty-nine artists in its sprawling 160,000 square feet of exhibition space.

Aspinwall House, Kochi-Muziris.

Unlike other art biennales, the Kochi Biennale is a largely bottom-up, artist-driven endeavor; a labor of love that has been fraught with funding and infrastructural hiccups. Despite these hurdles, it has endeared itself to the art world, a testament to the vision and ambition of the organizers. A visit to the Biennale YouTube page reveals enthusiastic praise from artists and curators alike. Chris Dercon (Director, Tate Modern) lauds Kochi for being an accessible “people’s biennial” and blueprint for the ever-flexible “museum of the future.” Sheena Wagstaff (Chairman, Modern and Contemporary Art, Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art) exhorts, “If anyone is watching this, you have to get here!”

When a family reunion brought me to Mumbai this past December, I embarked on a side-trip to balmy Kochi, and spent two busy days at the Biennale. I could have easily used a third to revisit some of my favorite installations, and explore some of the collateral projects. Overall, what I found was a splendid and engaging display of art, one that was thoughtful in its curation and installation, appurtenant to physical site and vernacular history, while expounding on the curatorial premise in poetically resonant gestures. Also heartening was the eclectic mix of visitors, in particular the large number of locals of all ages and socio-economic strata who appeared to be engrossed by the art (The inaugural Kochi Biennale in 2012 attracted nearly 500,000 attendees, and the organizers are optimistic for a more robust attendance this time around).

In the catalog foreword, Jitish Kallat identifies two parallel points of departure which informed his curatorial vision: the 15th century maritime “Age of Discovery” which brought traders and colonizers to Kochi; and advances in calculus and trigonometry made by the Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics during the 14th-16th centuries.[1] Indeed, motifs alluding to the nautical, cartographic, historical-temporal, and conjurations of the Universe recur in the art.

N S Harsha. “Punarapi Jananam Punarapi Maranam,” 2013. Acrylic on canvas, tarpaulin. 12×80 ft. Photo by Colin Fernandes.

Below are some of my personal favorites.

Tara Kelton, The Creation of Adam (2014)

I heard it before I saw it—that familiar welcome tone, repeating itself indefatigably. Kelton’s re-imagining of Michelangelo’s iconic handshake consists of a Nokia cellphone affixed to the ceiling at Aspinwall, the welcome screen of two hands meeting suspended on an endless loop. I craned my neck searching for the device, and upon locating it, grinned at Kelton’s wit.

Sahej Rahal, Harbinger (2014)

SFAQ readers may recall Rahal from an earlier article by this writer. (Full disclosure: He is an artist in my collection.) For the Biennale, Sahej spent four months on-site, populating a disused laboratory with fantastical objects sculpted from clay, polyurethane, hay, and found detritus: celestial seed pods, mutant four-limbed starfish, towering Bourgeois-esque arachnids, mitotic black spheres, mysterious winged creatures and proto-human faces emerging from the clay. I found this prodigious installation to have the chimerical flavor of a lab-experiment-gone-awry meets archaeological-excavation-from-the-future.

Sahej Rahal. “Harbinger,” 2014 (detail). Clay, polyurethane, hay, found objects. Dimensions variable. Photo by Colin Fernandes. Image courtesy the artist and Chatterjee & Lal

N S Harsha, Punarapi Jananam Punarapi Maranam (Again Birth, Again Death) (2013)

Referencing a Sanskrit hymn on the eternal cycle of birth and death, this sublime eighty foot canvas depicts the universe as a vertiginous ouroborus of swirling planets and stars. I walked its length multiple times, impressed by the majesty of its scale while also reveling in Harsha’s exquisite attention to detail, visible upon close inspection.

Ryota Kuwakubo, Lost # 12 (2014)

An LED affixed to a toy train creates a play of light and shadows as it traverses a course laden with market ware purchased in Kochi. Kuwakubo’s kinetic sculpture is remarkable for how much he has accomplished with the most quotidian of objects. The immersive landscape beguiled me.

Theo Eshetu, Anima Mundi (2014)

I spent a full half hour entranced by the kaleidoscopic paroxysms of images displayed on a video monitor, and reflected by a mirrored tunnel. Visuals include fluoroscopic views of the human body, tribal dances, feuding animals, and seemingly sadomasochistic rituals. A sense of imminent danger pervades the non-linear narrative.

Valsan Koorma Kolleri, How Goes the Enemy (2014)

Kolleri’s delicate intervention in the overgrown Cabral Yard, including subtly arranged twigs, leaves and other natural elements, suggests animism and occult rituals. I found this space to be haunting and quietly disturbing (think Season One of True Detective).

Sissel Tolaas, Fear (2014) and Benitha Perciyal, The Fires of Faith (2014)

Both these artists are notable for their effective use of the olfactory. Bearing literal and metaphorical weight, Fear consists of monolithic stones painted with the odor of 20 men who suffer from a phobia of bodies. More approachable and saccharine is Perciyal’s installation of Christian statuaries rendered in fragrant incense.

Jitish Kallat has articulated his intention for the Biennale to be a viewing device of sorts, “an observation deck to contemplate our world” and “toolbox for self-reflection.” He writes that Whorled Explorations seeks to “interlace the bygone with the imminent, the terrestrial with the celestial”.[2] My own encounter with the Biennale validates the success of his mission. Some might call the experience at once expansive and introspective, and deeply affecting or even spiritual. In my case, the art at Kochi trained my attention on the relationship between mankind and the vastness of cosmic space-time, nudging me to transcend my Self, and making me acutely aware of the fact that I am part of something larger.

And isn’t that what all great art should do?

Benitha Perciyal. “The Fires of Faith,”2014 (detail). Bark powder, frankincense, myrrh, cinnamon, cloves, lemon grass, cedar wood, coal, leather dried gourds, wood (re-used), perfume, essential oil bottles and assorted objects of daily use. Dimensions variable Photos by Colin Fernandes

[1] Jitish Kallat: Whirled Views/ Whorled Explorations. Short Guide, 2014. Curatorial Note, Kochi-

Muziris Biennale.

[2] Ibid.