Dictatorships, deportations, and the disappeared: the dark years of Latin American political and cultural repression were often marked by imprisonment, torture, and worse for those artists challenging the status quo, even in the most subtle of ways. From the 1960s to the 1980s, when the waves of repression were washing over the Southern Hemisphere of the Americas at their harshest, an open communication channel still remained. The international postal system, operating under universal treaty, encouraged a connection between a growing cadre of artists working in the margins of contemporary art, giving once-isolated individuals a global voice.

Marginal fields of art, divorced from commercial outlets, which these artists avoided, united them. Their choices of media were manifold, including artist publications of all kinds in periodical and book form, rubber stamps, postal stamps (artistamps), visual poetry, collage, photocopy and machine manipulated art, video, audio, performance, and political protest. These activities and media were manifested both individually and in cooperative actions, reflecting a developing group dynamic. The postal system provided the practitioners of these activities a long-distance social and cultural network in the mid to late 20th century anticipating the Internet. Through helping hands at home and abroad, Latin American artists encountered camaraderie in the face of censorship, arrest, and exile.

These artists, drawn to non-commercial collaborative artworks, both poetic and political in nature, were encouraged by a growing circle of international artists influenced by Marcel Duchamp’s broad conceptual approach to art. Duchamp was accumulating contemporary currency in the post-war era, uniting a new generation of critical thinkers. These practices included the obsessive letter writing of Ray Johnson, and the event scoring of Fluxus.

Both Johnson and Fluxus, following Duchamp’s lead, sought to disrupt the filter between art and life. Johnson’s artful correspondence was cloaked in the everyday activity of letter writing. Fluxus artists sought to raise the level of mundane actions to closer inspection. Brushing one’s teeth, cooking one’s meal, opening and closing doors—when placed in the context of contemplation and performance—brought new awareness to the commonplace, bridging art and life.

Argentinian Mail Artist Edgardo Antonio Vigo, who encouraged “an art that signals in such a way that the everyday escapes from the sole possibility of being functional. No more contemplation, but activity . . .” reflected this emerging attitude towards art and its relation to the everyday.

Often acknowledged as the father of Mail Art, Johnson had been schooled at Black Mountain College in the late 1940s, mentored by John Cage and Josef Albers. From Albers, he honed his design skills. From Cage, he learned to make something from nothing. Moving to New York, Johnson embarked upon a career in design, using the postal system to promote his intentions, and in the process, formed a growing core of correspondents fascinated by his unique approach to the activity.

In 1962, E. M. Plunkett identified and named Johnson’s practice the New York Correspondence School, a takeoff on the New York School of Abstract Expressionists. Johnson expanded art lessons by mail, including instructions to “add and pass” his incoming correspondence to either known or unknown persons.

That same year, Fluxus, under the organizational capabilities George Maciunas, began publishing and performing. Many of the New York-based Fluxus artists had studied with Cage in his composition class at the New School for Social Research in 1958. Yoko Ono had spread awareness of Fluxus to Asia. In Europe, several adventuresome artists, including Ben Vautier and Robert Filliou, involved themselves in the agenda set by Maciunas. By the end of the 1960s, Filliou was declaring the existence of an “Eternal Network” of artists, some entering, some leaving, but always a core group remaining to dispense an ongoing philosophy of a universal union among artists, featuring cooperation over competition.

Mail Art is concurrently a medium and movement. The utensils of the postal system— envelopes, rubber stamps, postage stamps, and philatelic practices, such as first-day covers and cancellations—become fodder for the practitioner. In this sense, we can un-capitalize “mail art,” and treat it like any other artistic media, such as painting, sculpture, printmaking, watercolor, etc.

I have chosen to capitalize the spelling of Mail Art to indicate acknowledgement that the medium has gained an international following, becoming a movement, which like other artistic movements of the past, has generated publications, exhibitions, histories, manifestoes, and institutional collection. The ongoing activity of thousands of artists utilizing the postal medium has earned the activity the right to “capitalize” itself.

As Mail Art diffused around the globe, various geographic regions acquired unique characteristics. Mail Art in North America took its lead from Ray Johnson and Fluxus. Neo-Dadaist in nature, it assumed a seemingly frivolous, art-for-art’s sake approach, incorporating but cloaking more serious issues, such as the decentralization, democratization, and decommodification of art based on principles earlier established by Marcel Duchamp.

In Western Europe, Mail Art tended toward an intellectual exercise, shorn of the frivolous camouflage employed by their North American counterparts. For some, especially in Eastern Europe, the stakes were especially compelling, and involving oneself in the activity had serious consequences. Europeans, such as Hervé Fischer, Jean-Marc Poinsot, Ulises Carrión, Romano Peli, György Galántai, and Geza Pernecky were among the first to write critically about Mail Art, promoting the theoretical and distributional innovations of the field.

Japan and South Korea were home to active Asian Mail Art practitioners. Ray Johnson had established contact with Gutai leader Jiro Yoshihara as early as 1957, his work appearing in Gutai magazine, resulting in the group’s transformation of traditional holiday greeting cards into Mail Art fodder. Multitudes of Mail Artists thrived in the atmosphere created by Shozo Shimamoto’s AU (Artists’ Union and/or Art Unidentified) organization, after his Gutai years. Individually conducted projects, such as On Kawara’s I Got Up at . . . and Mieko Shiomi’s Spatial Poem indicate the Japanese propensity to reach across borders for fellowship in the face of geographic divide.

Latin America is a different case. Mail Art in the Southern Hemisphere of the Americas appeared early, was widespread, and assumed an important place in the network of international alternative art practices. The relatively liberal 1960s, when waves of generational change swept over Latin America, as they did elsewhere, gave way to a tsunami of repressive governmental interference in the lives and art of its people the following decade. Rising to the occasion, many artists turned to direct involvement in politics and social reform.

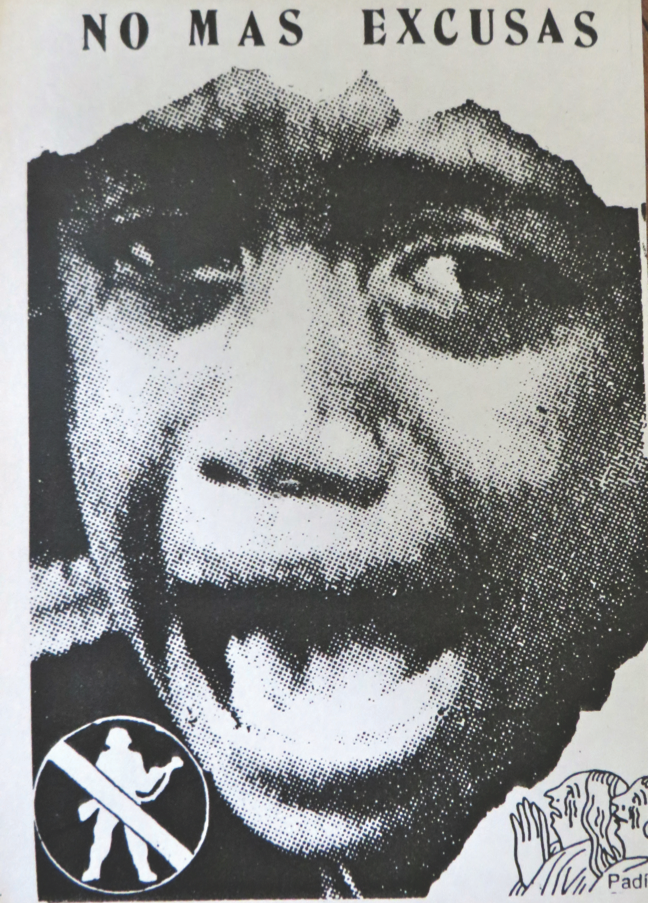

Uruguayan visual poet and Mail Artist Clemente Padín tried by a military court and imprisoned in August 1977 for “attacking the morale and reputation of the army,” writes that, “Almost naturally Mail Art has become an instrument of battle and denunciation calling on the tenacity of our peoples to win better, more humane living conditions, under the sign of social justice and peace.”

Paulo Bruscky, in his essay Mail Art: The Art of Communication states that, “Mail Art appeared at a time when communications, as well as other means of expression, were becoming more difficult. During this time, official art, seemed to involve speculations of the private market . . . Mail Art, the art of correspondence . . . is no longer a minor thing. It is the most viable art system available in recent years. The reasons are simple. It is anti-bourgeoisie, anti-commercial, anti-system, etc. This art has shortened the distance between people and between countries, as shown by expositions and communication centers. In these places the art was not judged nor awarded, as things were in the old showrooms and bi-annual meetings. With Mail Art, art regains its main functions, information, protest, and denunciation.”

Clemente Padín, No Mas Excusas, Circa 1990. Postcard, Montevideo, Uruguay. Collection of John Held, Jr.

Padín writes that, “Towards the beginning of the 1960s, various South American artists—poets and visual artists—made art projects and distributed them through the mail, without using the term ‘postal art.’ Among them were Edgardo Antonio Vigo from Argentina, the Chilean Guillermo Deisler, and the Uruguayan Clemente Padín. Also at that time the North American group Fluxus took up Mail Art and mass communications events, following similar antecedents established by the Dadaists, Futurists, and Surrealists.”

Towards the end of the 1960s, long-distance communication among artists accelerated, and the postal system was increasingly seen as a medium through which art could be generated. A project that placed the postal system front and center of artistic attention, and often acknowledged by early practitioners of the field, occurred in 1969 when visual artists Liliana Porter and Luis Camnitzer conceived of a project demanding multiple mailings, sponsored by the Torcuato di Tella Institute in Buenos Aires.

Years later, Camnitzer, in his 2007 book Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation reflected upon the situation confronting Latin American artists: “The epidemic of dictatorships that spanned Latin America from the sixties to the mid-eighties made the use of mail a perfect vehicle to allow for the communication between isolated artists and the rest of the world. The network became important enough to justify the organization of international exhibits in Uruguay (1974), Argentina (1975), and Brazil (1976), and in Mexico and other countries shortly thereafter. The notoriety of these efforts had two consequences: the number of mail artists increased greatly and censorship became more sophisticated and intense.”

In 1971, a meeting occurred in Buenos Aires at the Center of Art and Communication (CAYC), a major distributor of information about alternative arts throughout Latin America, administered by Jorge Glusberg, who directed the organization from 1968 until his death in 2012. The event occurred at the opening of the exhibition International Exhibition of Propositions to Realize and brought together some of the key players in the Latin American Mail Art community in an early display of solidarity.

Edgardo Antonio Vig, an Argentinian artist from La Plata, curated the exhibition, attracting the attendance of Uruguayan artist Clemente Padín and Guillermo Deisler from Chile. All three artists had become acquainted with one another’s work in 1967 when they began to publish art periodicals dealing with visual poetry. Padín’s magazine OVUM, Vigo’s Diagonal Cero, and Deisler’s Ediciones Mimbre, were distributed within and outside South America. In these early years, Mail Art was not the connection for these artists, rather their interest in visual poetry. Their publication activities, along with Venezuelan Dámaso Ogaz’s C(art)A brought them into contact with international artists, notably Julien Blaine in France, members of Fluxus, and General Idea in Canada, who were distributing FILE, the major Mail Art info-zine of the era.

The first exhibition of Mail Art in South America, Creative Post-Card Festival was curated by Clemente Padín at Gallery U in Montevideo, Uruguay, from May 11 to 24, 1974. Ismael Assumpção organized the First Internationale of Mail Art from September 7-15, 1975 at Caixas College in São Paulo, Brazil. Three months later, the Last International Exhibition of Mail Art took place at the New Art Gallery in Buenos Aires, Argentina, curated by Edgardo-Antonio Vigo and Horacio Zabala. A year in the making, the exhibition attracted the participation of 199 artists from 24 countries.

In the same month as Vigo and Zabala’s Last International Exhibition of Mail Art and following Ismael Assumpção’s First Internationale of Mail Art, some months previous, Paulo Bruscky and Leonhard Frank Duch organized the First International Exhibition of Mail Art. Duch wrote that the exhibition “was based on the idea of bringing together all the material received from many friends in Mail Art, although they weren’t abundant. We wanted to do the exhibition through the mail, but we did not receive permission. Then we put it up in a large room of the Barão de Lucena Hospital, a government hospital. There was an immense table with glass and we put the works under glass.”

Another Mail Art exhibition was planned by Bruscky and Duch in August 1976, but the political realities of the time intervened. In a letter to Clemente Padín, dated March 2, 1977, Bruscky stated that “it was prohibited and censored by the police, and even we (the organizers) were prisoners for three days. The exhibition was closed one hour after its opening . . .”

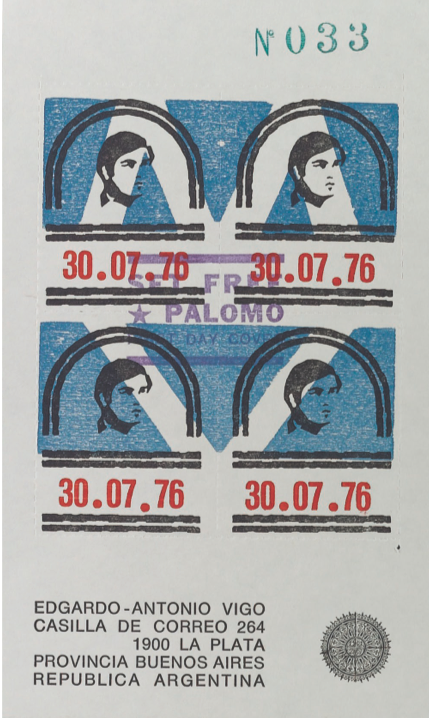

Padín writes that, “During the period of the dictatorships mail art turned totally to the denunciation and exposing of the national internal situation . . . thus we cite the closing by the Brazilian military of the II International Exhibition of Mail Art organized by Paulo Bruscky and Daniel Santiago in Recife in 1976; the brutal exile of the mail artist Guilermo Deisler after Pinochet’s and the ITT’s conflict with Allende . . .; the kidnapping of Palomo Vigo, son of the Argentine mail artist Edgardo-Antonio Vigo; the torture and incarceration for many years of the Uruguayan mail artists Jorge Caraballo and Clemente Padín; the persecution, incarceration, and the exile of the Salvadoran mail artist Jesús Romeo Galdámez, now in Mexico; the suspension of the civil rights of Andrés Díaz Poblete, son of the Chilean mail artist Eduardo Andrés Díaz Espinoza.”

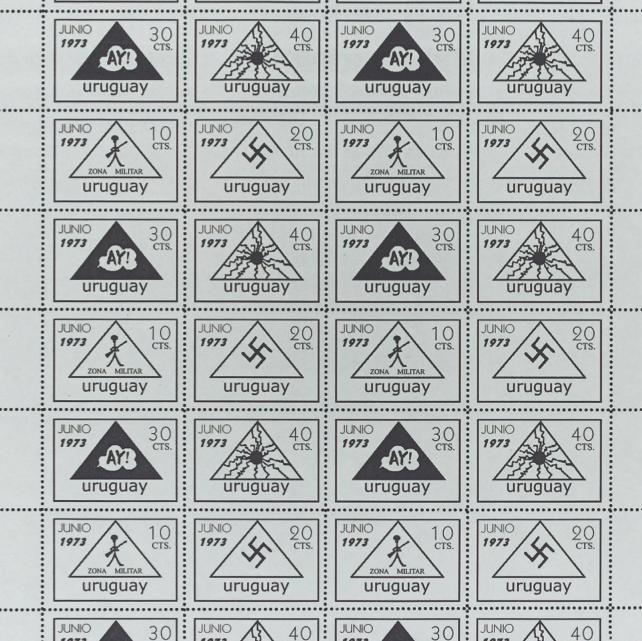

Padín himself received some of the harshest treatment at the hands of the authoritarian government. “In 1974, during the Uruguyan military dictatorship, I organized the first Latinoamerican Mail Art exposition at Galeria U. in Montevideo, Uruguay. My edition of apocryphal mail art stamps denounced the dictatorial regime for its brutal suppression of Uruguay’s human rights and this eventually led to my imprisonment from August, 1977 to November, 1979.”

For Padín in 1977 there was no choice between art for social reform and “art for art’s sake.” His imprisonment was an important turning point in Mail Art, for when word of his arrest in the international artistic community (“The Eternal Network”) became known, it became obvious to all that art was not merely a game, decoration, or a career path, but a weapon that could be used in the face of societal injustices with life and death implications.

San Francisco poet Geoffrey Cook and French visual poet Julien Blaine spearheaded an international effort to gain the freedom of Padín and fellow Uruguayan artist Jorge Caraballo. The campaign to gain their release was two-pronged: “(1) encourage individuals to write their governments and the government of Uruguay to circulate information about the case, and (2) to win the support of influential individuals, organizations, and governments to intercede on the release of the artists.”

Edgardo-Antonio Vigo, Set Free Palomo First Day Cover, 1976. Postcard. La Plata, Argentina. Collection of John Held, Jr.

Caraballo was released shortly after his detention, arrest, and conviction. Padín languished in prison until 1979, shortly after his predicament reached the attention of the American and French ambassadors. In reviewing the episode, Cook wrote, “What did we accomplish? We did what we could, and it may have convinced the Uruguayan government that whatever they did to the artists would not be done in the dark. We may have convinced them that negative actions would be counterproductive to their own goals. The project has shown us that structures exist within the art world through which we can affect change and influence larger forces. The project represents a small cry in a collapsing universe.”

Padín was not alone in his suffering for the sake of artistic practice directed toward social justice during these years of repression in Latin America. His friend Guillermo Deisler, of German heritage living and teaching in Chile, was arrested for two months after the September 11, 1973 military coup in Chile, before friends were able to obtain a French visa for him. After a few months, he decided to move to East Germany with his family, and after a meeting with fellow Chilean refugees, he decided it would be best to relocate to Plovdiv, Bulgaria. In 1986, he returned to Halle, East Germany, where he remained until his death on October 21, 1995. His collection of over 5,000 Mail Art works is now located in the archives of the Academy of Art in Berlin.

Writing of his friend, Clemente Padín illuminates the mindset of the emerging Latin American artist coming of age in the 1960s: “Guillermo Deisler’s formation was not very different of that of many young artists who, toward the ‘60s, were emerging in the scene of Latin American art, marked to fire by the more important social-political factors in the history of our countries, after the independence struggle of the past century. The Cuban Revolution was the point of departure of nearly all our generation and guided and impelled us in the struggle for eradicating social differences on behalf of a just and solidary society.”

Deisler stated that, “For the Latin American people—and we are already quite a number of creators that, voluntarily or impelled by political circumstances, have been obligated to the exile community—Mail Art becomes the palliative that neutralizes this situation of ‘expired citizens,’ [as] Paraguayan writer Roa Bastos [calls] this massive emigration of ‘workers for the culture’ from the South American continent.”

The imposed exile and enforced global meanderings Guillermo Deisler took did not deter his positive outlook on life. In the titles of two of his many publications over the years, we catch a glimpse of his determination to move beyond victimization. UNI/vers(;) gathered works of visual and experimental poetry from the international community in 35 issues from 1987 until his death. It suggests the notion of a global creative brotherhood based on the individual and extending outward. His Peacedream Project was an assembling magazine, asking contributors to submit 100 copies of their work for distribution. Along with his rubberstamp, “pARTner,” Deisler’s “peacedream” suggests a passion for international understanding and community in the face of political adversity and geographical distancing.

The relative freedom Deisler enjoyed in Eastern Europe, due in part to his persecution for communist sympathies elsewhere, gave him the opportunity to spread the practice of Mail Art under two of Eastern Europe’s most repressive regimes. His struggle for artistic integrity in the face of political pressures, his continuing expression of ideals exemplified in the concept of an “Eternal Network,” and his outreach to other Eastern European artists denied an outlet for their outreach to contemporaries abroad, endeared Deisler to the international Mail Art community, which cheered his positive approach to life despite hardships unimaginable to most.

I have mentioned the effect Deisler’s political persecution had not only on himself, but his family, who shared the artist’s refugee status in shifting dislocating environments. His was not the only family to experience agonies. Edgardo Antonio Vigo lost a son to the campaign of disappearances experienced by Argentinians. In 1976, his son Abel Luis (“Palomo”) was kidnapped and never heard from again. A vigorous campaign was undertaken within the Mail Art community to determine his whereabouts and to “Set Free Palomo.”

Fellow artist Graciela Gutiérrez Marx from La Plata joined the Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo (Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo) in support of Palomo Vigo, forming a bond that resulted in the two collaborating under the pseudonym G. E. Marx Vigo from 1977 to 1984. Collaborating on both textual and visual materials disseminated throughout Latin America and beyond, the two artists became inspirational figures in the wider network. Their artfully mailed manipulations mark a high point in Mail Art collaboration.

They were not alone in bringing attention to those missing during the era of repressive regimes. A description of a recent exhibition of the work of Paulo Bruscky states that, “For our missing ones, a collaged postcard from 1986 that features the faces of three people who went missing under the military regime in Recife exemplifies Bruscky’s pioneering role in the Mail Art movement. By mailing cards like these across the globe, Bruscky turned his artworks into political tools that allowed him to develop an international network of people who were aware of the persecution and infringements of civil liberty that the artist and his contemporaries were experiencing in Recife.”

Taken from the first book written on Latin American Mail Art, EL Arte Correo en Argentina by Fernando Delgado and Juan Carlos Romero of the Buenos Aires arts organization Vortice Argentina, the words of essayist Belén Gache express the sentiments of most examining the field. Mail Art in Latin America was a necessary expression—sometimes dangerous, sometimes effective—against the virulent violent culture of the era. “In Latin America, Mail Art rises as an activity linked to the resistance against that political and cultural repression that convulsed the continent in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The diffusion and expansion of this artistic form related directly to a will to denounce the local violence situations through envelopes, stamps, seals, chains of interchange, etc.”

That era passed, and Mail Art forged on. As political turbulence lessened in many of the countries, Latin American Mail Artists built upon a rich heritage of rage and resistance, pursuing social justice while publishing an increasing number of periodicals, exhibiting expanded amounts of “art at a distance,” and staging performances in support of issues of both a local and universal nature. Some bemoaned the lessening of urgency the medium addressed, and it was true that art made in less politically intrusive times may have, on the surface, seemed frivolous in comparison.

Luis Camnitzer, nearing completion in his book Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation, with the chapter, “From Politics into Spectacle and Beyond,” laments the changes that followed in the wake of lessening tensions. “In Argentina, many artists from the Tucumán Arde [a vanguard politically orientated art group from the late 1960s] generation stopped their artwork completely. In Brazil, many of the artists who at the beginning of their careers were strongly rooted in a political context slowly moved away from merging art and politics, and evolved to a point where their information would be acceptable for formal exhibition. Politics remained, but in most cases they became exhibitable politics. The shift did not necessarily mean a true and general political and ideological softening, but it certainly indicated a shift in the ambitions for a definition of an audience and a resignation about the dimensions of the consequences art making could have for society at large.”

Not all agreed that a downward shift took place, rather an ensuing renovated vigor. Clemente Padín, writing in Network, Mail Art, and Human Right in Latin America, states that, “Undoubtedly the permanence of Mail Art for so many years has weakened the strength of the primitive rebellion, when it questioned the rest of the artistic disciplines, forcing them to recompose their structures taking in consideration its controversial proposal. Nowadays, although its process of institutionalization has greatly increased and it is almost integrated to the cultural frame of legitimation of the social status, it still keeps its power of calling and its ethical strength . . . The emerging generations based on the critical reading of Mail Art and its use in both graphic and distributing means, that new times offer them, will know how to revive this international artistic instrument deeply involved in its time and what is human.”

The number of exhibitions in Latin America after 1985 retaining political and social motifs signified the enduring retention of resistance to injustice within the regional Mail Art network. In 1986, Gilbertto Prado of Brazil organized Stop the Star Wars. That same year, Clemente Padín, never far from his political foundation, organized an exhibition against apartheid. Guillermo Deisler, ensconced by exile in East Germany, organized International Mail-Art: For Chile and Latin America. The first Mail Art exhibition took place in Cuba in 1990 when Pedro Juan Gutiérrez curated the exhibition Project Mail Art to Cuba. Also in 1990, at the height of troubles in Medellín, Columbia, Tulio Restrepo organized the exhibition Zona Postal. In 1992, Carlos Montes de Ocacurated Urgent Mail Art Show accompanied by a catalog containing an essay by Guillermo Deisler. Celebrating the Cuban patriot José Martí, Clemente Padín organized an exhibition on his behalf in 1995.

Vortice Argentina was indicative of the way Mail Art would trend in Latin America after the era of bloody regime changes. Formed in 1997, the organization was mindful of Mail Art’s Argentinian heritage, one of the founders being Juan Carlos Romero, an active figure in the early publications and exhibitions staged by Vigo, Zabala, Glusberg and others participating in the early to mid-1970s. Fernando Delgado was a newer but no less energetic adherent to the field, who had begun publishing a Mail Art magazine Vortice in 1996. The following year, the periodical changed its name to Vortex, a “Visual Poetry and Experimental Graphic publication,” edited by Delgado and Romero. In 1998, Delgado opened Barraca Vorticista, one of the first galleries in the country devoted to Mail Art and Visual Poetry. An archive was also established to document the arriving Mail Art, and an online website was designed to share the work internationally. In late 1996, the organization was given a grant by the National Art Fund to support the publications it was producing. The activities of Vortice Argentina, including a special website devoted to Edgardo Antonio Vigo, were acknowledged by the Argentine Association of Art Critics in 2001.

It was E. A. Vigo who introduced Juan Carlos Romero to the international Mail Art network in 1970, and as such, Romero participated in many of the seminal Latin American Mail Art activities including the Mail Art section organized by Walter Zanini as part of the São Paulo Biennial in 1974, and The Last International Mail Art Exhibition, organized by Vigo and Zabala in 1975. Romero was also included in an important early 1974 publication, Herve Fischer’s Art and Marginal Communication published in France.

“During the military dictatorship between 1976 and 1982,” Romero writes, “I narrowed my participation in Mail Art considerably, starting again a few years later when I collaborated for Argentinian publications like Hoje Hoja Hoy [edited] by G. G. Marx and Hilda Paz, 1985, [and] Edgardo Vigo’s International Book of Stamps and Postmarks (1991) . . . In 1996, though the Vortice publication, I met Fernando Delgado, with whom I organized several projects . . . [including] from 1999 the annual projects Mail Art Day and Visual Poetry Meeting.”

In one of several essays in the catalog, Montse Fornós and Matriz Grupal continued to stress the importance of activism implicit in Latin American Mail Art. “If in all its years of running and experience, Mail Art has been able to abolish the barriers from its network, it must continue working to open doors to dialog. The change and the creativity, to demythologize art and to rescue its collective function, to leave the mere aesthetic contemplation of works and to offer the possibility of acting, to imply the observer as participant, and to make possible the expression of the majority to oppose these social events that violate the elementary rights of humanity.”

In 2005, Delgado and Romero published the first full-length book on Latin American Mail Art, El Arte Correo en Argentina (Vortice, Buenos Aires, 2005), which concludes with the essay DODO not DADA by distinguished Italian Mail Art practitioner and theorist Vittore Baroni. Baroni ponders the current situation of post-millennial Mail Art, questioning, “So, is Mail Art still alive or (almost) extinct?”

“Though I never stopped swimming in the correspondence flow since I first entered the postal network way back in the late seventies, this question is becoming more and more difficult to answer. The Mail Art community, if there ever was one, from my observation point seems to be receding into utter obscurity or melting into (inter)net art, which is a wonderful but rather different kind of experience. Yes, there are still Mail Art shows and ‘festivals’ being organized around the (Western) world, but the medium has become a bit stale and tired, the original feeling of excitement and discovery is long gone (and this is understandable for a phenomenon that spans four decades, no small feat in itself!) but it has not been replaced by the wisdom and maturity that old age usually brings forth.”

“Things have changed a great deal in the almost thirty years I spent inside (and outside) the postal net: riding on the crest of the new wave/punk energy in the seventies, but still maintaining the positive ideas of the hippie era. Resisting the boredom of the eighties and nineties, clinging to the collectivist utopia of a free-for-all and open trading system, entering the new millennium to find out that, after all, maybe those cynical punks were right, this is a ‘no future’ situation for the planet. Evil forces prevail, the model for global cooperation that Mail Art so well exemplified proved inapplicable to the big numbers. Maybe all the money we dumped in postage stamps and photocopies would have been better invested in some charity project, maybe a little voluntary social work would have been less wasted time.”

During the dark period of political upheavals, the practice of Mail Art in Latin America was itself a political statement. The mere act of reaching out to the wider world threatened forces seeking to control the flow of internal information. A participatory art, one that was open to all, with no judgments of quality was subject to suspicion in a political climate seeking to stifle individuality. When one stumbled upon Mail Art—in a magazine, exhibition space, or classroom—one could not help but be enchanted by the freedom of creativity expressed in the face of adversity. And, if others could do it, perhaps . . .