All Exit

Jennifer and Kevin McCoy

25 October 2014–3 January 2015

Johansson Projects

2300 Telegraph Avenue, Oakland, CA

By Kate Haug and Kelly Inouye

All Exit at Johansson Projects reflects the problematic cultural and economic output of Silicon Valley. The Brooklyn-based artist duo Jennifer and Kevin McCoy acknowledge that Californians are living in a strange place, not in terms of the precise characteristics of our physical location, but in the moment in which we live, where one set of values and order is being upturned by another.

Through hybridized dioramas assembled to depict wasteland mash-ups of corporate headquarters and dystopian landscapes, the McCoys liken tech “titans” such as Gordon Moore, Peter Thiel, and Larry Ellison to adolescents playing master-of-the-universe fantasy games.

The results of these artists’ musings on what their statement describes as “remote viewing” and “speculative modeling” are clever and fun. There is great need for meaningful discussion of the economic and cultural impact the tech economy is having on the Bay Area. It’s admirable to tackle the topic, and interesting to view an outsider’s perspective, especially that of such accomplished artists. The McCoys have exhibited their work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, PS1, the Museum of Modern Art, and the New Museum. Grants include a 2002 Creative Capital Grant for Emerging Fields, a 2005 Wired Rave Award, and a 2011 Guggenheim Fellowship.

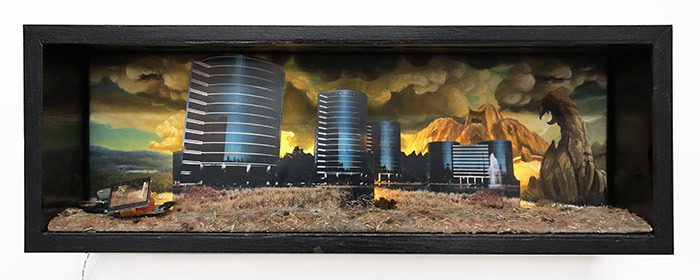

Jennifer + Kevin McCoy, “Dominion,” 2014. 30 x 9.5 x 9 in. Courtesy of the artists and Johansson Projects.

Much of their past work has examined changing conditions around social roles, categories, and genres, questioning how meaning is established and how cultural memories are formed. All Exit focuses their gaze directly on representations of Silicon Valley online and in the media. Prior knowledge of the McCoys’s history of dissecting second-hand experience contributes greatly to reading the works on display at Johansson Projects.

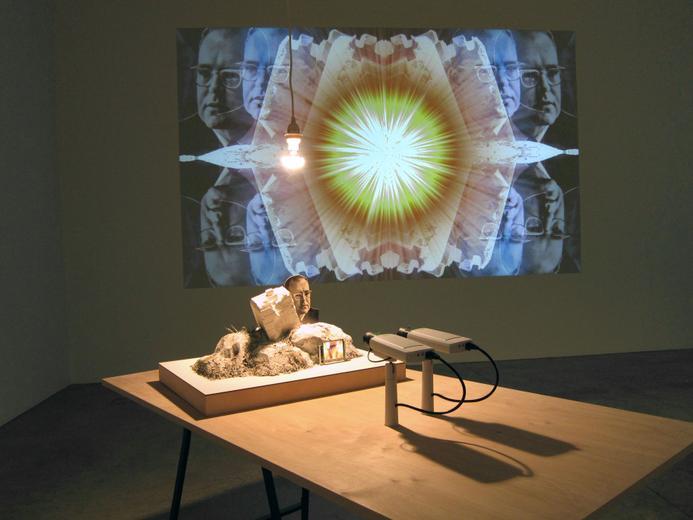

In the gallery’s main space, Priest of the Temple consists of a miniature crumbling office building that juts out of a pile of gravel meant to replicate a mountain along with what would be a monumentally sized portrait of Gordon Moore, founder of Intel. Two video cameras trained on this table-sized diorama project a rotating mandala comprised of Moore’s head, the crumbling landscape, and a central undulating star. The cameras are programmed to gradually multiply, distort, and rotate Moore’s face and the landscape more and more until the sequence resets. The piece is meant to obliquely reference Moore’s Law, which states that the number of transistors incorporated into a microchip will double every twenty-four months. The installation as a whole reads as a type of altar, immediately conjuring images of another priest of a different dystopian temple: L. Ron Hubbard. The gallery’s description of the piece states that in 2005 Moore added that “the law can’t continue forever. The nature of exponentials is that you push them out and eventually disaster happens.” Interestingly, there is no mention of this on the website for Intel’s interactive museum in Santa Clara where visitors can “go behind the scenes in the high-tech world of California’s famed Silicon Valley.”

Jennifer + Kevin McCoy, “Priest of the Temple,” 2012. 43 x 30 x 60 in. (13 x 20 x 24 in. sculpture). Courtesy of the artists and Johansson Projects.

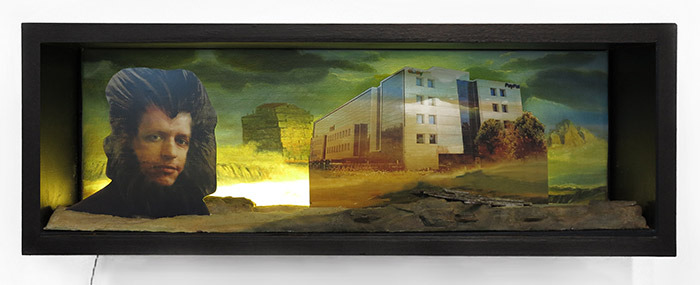

In contrast, Shore Leave features libertarian billionaire and PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel lording over a hybridized landscape, which includes the PayPal building surrounded by a landscape copied from the Forbidden Island fantasy board game.

The “exit” of the show’s title refers to a theory found in Albert O. Hirschman’s 1970 book, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. Hirshman posits the idea that if citizens do not like their government they can exit (leave/emigrate) or voice (engage in politics). The show’s title points, in part, to the all-exit strategy of Peter Thiel, who has given over one million dollars to the Seasteading Institute whose mission is “to establish permanent, autonomous ocean communities to enable experimentation and innovation with diverse social, political, and legal systems” (see Wikipedia). The feudal land owning habits of Larry Ellison, current reigning prince of his own Hawaiian island, Lanai, are the basis of the piece titled Dominion.

Constant World consists of a molecular looking mass of wires, cameras, steel balls, rods, and lights. This modernist space-age chandelier contains nine live video cameras trained on tiny dioramas built on black disks within the piece. Each camera feeds to a video monitor on the wall for a short time, presenting (in the artists’ words) “ . . . a utopian world that acts as its own advertisement.”

In a way, Silicon Valley has created a machine of eternal self-promotion. On the Internet, banner ads follow you from website to website, technology becomes obsolete within months of purchase, and Silicon Valley companies actively promote themselves as agents of positive change.

Peter Thiel’s escape routes from government, social programs, taxes, and democracy include cyberspace, outerspace, and Seasteading. Mr. Thiel outlines his idea in a 2009 essay titled The Education of a Libertarian. Unfortunately, only a few will be able accompany Mr. Thiel on his voyage. One only has to step outside of the gallery on to the streets of downtown Oakland to realize that many of our citizens will not be on the Thiel ship.

Jennifer + Kevin McCoy, “Constant World,” 2014. 4 x 4 x 4 ft. Courtesy of the artists and Johansson Projects.

Many of the current populist-tech fantasies promote the notion that technology will transform society to become richer, more democratic, more educated, and more egalitarian. And in some cases this is true. Yet as we stroll through many of the Bay Area’s low-income neighborhoods—the Tenderloin where homeless and mentally ill people sleep on the streets, the Mission where many families live below the poverty line, downtown Oakland where urban blight is on the cusp of being pushed out by gentrification—it’s all too clear that most technology companies have not contributed to the wellbeing of anyone outside their social networks. That is to say, in the Bay Area, poor people have not received significant benefit from being at the epicenter of tech’s cultural and financial revolution.

Of course, technology companies are businesses and not governments. They are designed to make money for their owners and shareholders, not to help people. Governments provide programs to alleviate poverty, to prevent child abuse, to help mentally ill people stay off the streets, to provide clean water, and to educate our population. In the last decade, the marketing machine of technology companies has worked hard to make us forget that governments—not businesses—are part of the real key to solving human problems.

Jennifer + Kevin McCoy, “Silicon Flats,” 2014. Single channel video collage, custom electronics. Overlapping images of Silicon Valley’s natural environment, its industry, and the architecture of its suburban technology headquarter buildings. 9:50. Courtesy of the artists and Johansson Projects.

The 20th-century belief that technology was created to help us, to help us solve human problems, to help make the world a better place, was a belief that technology was an extension of our better selves in solving poverty, improving medicine, and saving the environment. We were optimistic and it appears that that fantasy of technology as a savior and salve of humankind might be usurped by its day-to-day employment of casual hook-ups, the trading of cat videos, and the monitoring of everyday consumer purchases by multi-national companies.

In this new economy being pioneered in the Bay Area, where so much wealth is concentrated in the hands of so few, where the majority of jobs created are opportunities for service work with companies such as Uber, Instacart, Postmates, and Task Rabbit without benefits or stable salaries, where corporations are given tax breaks and allowed to park their staggering bank accounts overseas to avoid contributing to the funding of public programs and utilities meant to ensure a decent quality of living for all—it’s actually frightening to dismiss this all as a sinister game. We know it’s not a game to Peter Thiel; it’s an unfair set of rules that he must transcend. In his own words, Peter Thiel believes: “The fate of our world may depend on the effort of a single person who builds or propagates the machinery of freedom that makes the world safe for capitalism.” In other words, start building your space ships.

Jennifer + Kevin McCoy, “Shore Leave,” 2014. 30 x 9.5 x 9 in. Courtesy of the artists and Johansson Projects.

Kate Haug

Kate Haug is an artist, writer and mother. Her most recent project, Public Post, is a wheat paste poster series that addresses contemporary culture and technology.