Japanese Mail Art, 1956-2014

Mail an Octopus with Stamps on its Head

By John Held, Jr.

This essay has been pulled from SFAQ print issue 17.

Shozo Shimamoto (Nishinomiya, Japan). “Universe Okutopus.” Offset Print, 1987. Courtesy of private collection.

We are constantly adding to the art history of our time by ferreting out forgotten avenues of marginal art and artists. With newly arrived materials added to archives, and a new array of technological research tools to access them, these mislaid artists and their works are fast coming to the fore. Modernist art can no longer be viewed solely as a European phenomenon, rather a global one, with interconnections glaringly apparent when mislaid lines of communication between the cultures are finally intertwined.

There can be no history of mail art without an account of the Japanese contribution. Mail art in Japan can be directly traced to the 1956 correspondence of Ray Johnson, the oft-acknowledged “father of mail art,” with Jiro Yoshihara, sponsor and artistic coordinator of Gutai. Johnson had been an avid letter writer in high school, his postal encounters increasing after graduation from Black Mountain College amidst attempts to establish a career in design and a reluctance to expose his work in the usual forums. He began using the postal system in a poetic fashion, exposing the commonplace communication conduit as a potent purveyor of artistic practice.

The first act Yoshihara took when establishing the Gutai Art Association in 1954, was the publication of Gutai magazine, assigning twenty-six year old Shozo Shimamoto to be its editor. Printed at Shimamoto’s home in Nishinomiya, a suburb of Osaka, the magazine was the group’s initial outreach to the international art culture that Yoshihara, a wealthy businessman, had been keenly aware of for many years, carrying subscriptions to a variety of foreign journals.

Murakami Saburo, “Passing Through,” 1956. Performance view: 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition, Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo, ca. October 11-17, 1956. Photo: Otsuji Seiko Collection,Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo © Otsuji Seiko and Murakami Makiko, courtesy Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Photo: Otsuji Kiyoji.

Yoshihara’s particular passion after WWII was Jackson Pollock. In the American artist, he sensed the passage of painting beyond figuration and abstraction he sought. Gutai, a name given to the group by Shimamoto, meant “concrete,” implying the creation of the artwork through direct physical interaction between the material and the artist. Shimamoto fired containers of colored pigment from a canon onto a canvas. Kazuo Shiraga painted with his feet and crawled through a mixture of concrete and dirt. Atsuko Tanaka painted with sound, her exhibited bells awakened by audience participation. Gutai was this and a great deal more, and only currently recognized for their significant contributions to the Modernist canon.

Recently uncovered communication between Gutai and Pollock surreptitiously led to correspondence with Ray Johnson, initiating new directions in Gutai artistic practice. Moving to New York City after his Black Mountain College years, Johnson began to establish a network of correspondents through the postal system. Shimamoto sent several copies of the magazine to Pollock on February 6, 1956, accompanied by a letter seeking an opinion on the magazine. After Pollock’s death on August 11, 1956, his widow asked Bruce Friedman, the artist’s biographer, to help sort through the painter’s papers. Among the holdings of the collection, were the multiple copies of Gutai magazines sent by Shimamoto. Friedman not only wrote to Jiro Yoshihara, expressing interest in receiving further issues of Gutai, but passed on copies to his friend Ray Johnson, who contacted the group directly in 1957.

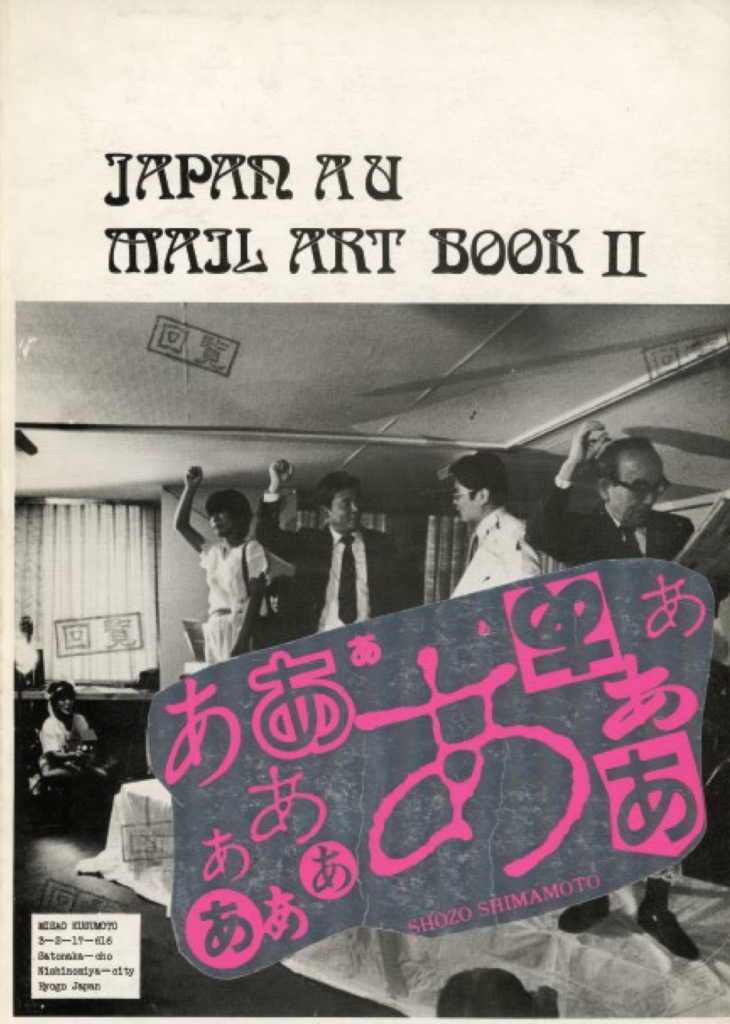

Misao Kusumoto, Ed. “Japan AU Mail Art Book II,” 1983, Nishinomiya, Japan. Courtesy of private collection.

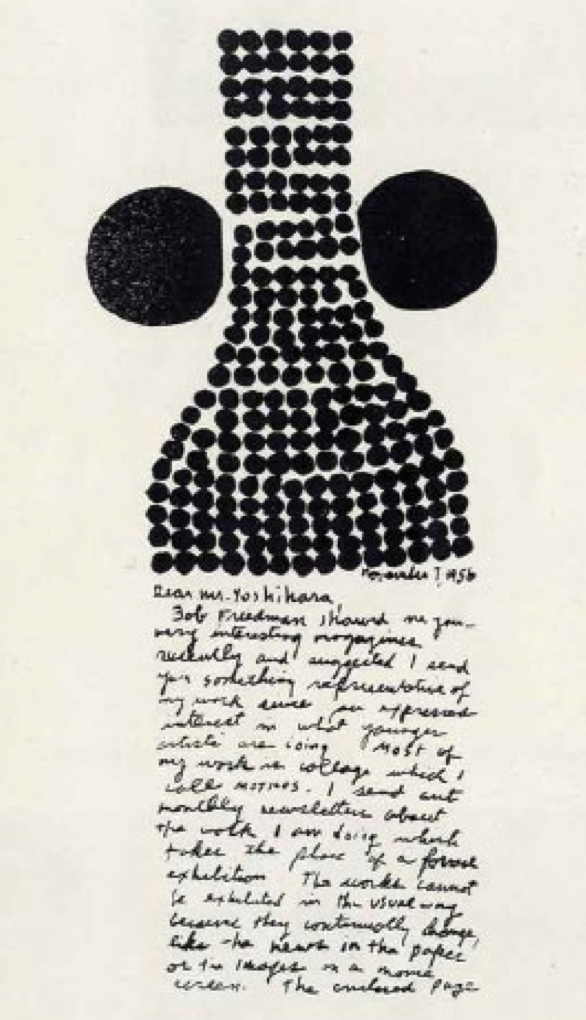

In a letter dated November 7, 1957, published in Gutai magazine, Johnson wrote to Yoshihara:

“Dear Mr. Yoshihara,

Bob Friedman showed me your very interesting magazines recently and suggested I send you something of my work since you expressed interest in what younger artists are doing. Most of my work is collage which I call MOTICOS. I send out monthly newsletters about the work I am doing which takes the place of a formal exhibition. The works cannot be exhibited in the usual way because they constantly change, like the news in the paper or the images on a movie screen.

The enclosed page shows small black patterns reduced in size, silhouettes of the MOTICOS. The actual MOTICOS are 12 inches in size. Pieces of paper, drawings, words, poems, language, string, each glued on a card. Sometimes the MOTICOS are tied with string to a panel; some of them are used as one group. Those MOTICOS are moved by the wind or by the weather; just like dead leaves, the heat preserves them. A famous artist will visit Japan soon. Her name is Sally Sheeves (?). I think you will meet her and see her works.

Ray Johnson ”

[Author’s note: Sally Sheeves translated incorrectly for the artist Sari Dienes] Yoshihara replied to Johnson on March 28, 1958.

“Dear Mr. Johnson,

I regret my delay in recognizing both your letter and the model of your works.

Due to my illness and the uncertain plans relative to the publication of the next issue of Gutai, I have been delayed in replying to yours.

Your letter made all of us very glad and we would like very much to include that fancy form you sent to s in our next issue.

You are so new and original. We were all surprised and interested in it very much. We would like to insert that in the April issue, which we will send to you as soon as it is in print.

In our next issue we would like to include some of the works from France. Mr. Tapie, a French critic will send us various materials. We want very much to introduce to the Japanese people some American works, so I hope you will be kind enough to send us as many of them as possible.

I regret to say I could not see Madam Sary Siebes. Thanking you again for your works and for your good interest in what we are doing, I am

Most cordially yours,

Jiro Yoshihara.”

In Gutai number 6, Yoshihara wrote that Jackson Pollock was, “a master American artist,” showed “keen interest” in Gutai, and that following his death, Pollock’s friend B. H. Friedman, had corresponded with the group, providing them with an essay, in which he confronted Pollock’s detractors and made a case for his lasting contribution (“It’s hard to accept an art in which there can be no tricks, in which every act is visible.”).

In addition to contributing the essay on Pollock by Friedman, it was mentioned that, “Mr. Fried- man introduced us to an unusual artist in New York, Ray Johnson, who presents his works not through exhibitions but in the form of correspondence. Mr. Johnson sent us new forms of paper cutouts, prints, poems, etc. The members of the Gutai group were very excited especially by Mr. Johnson’s method of presentation.”

After receiving Johnson’s missives to the group, Gutai’s use of the mails as a creative force sharply increased. Members of the group began using the form of New Year greeting cards, called nengajo, to distribute original works of art. In essence, Gutai members did away with the traditional practice of conveying holiday messages, substituting instead the presence of the artist through performative actions. Nowhere is this more innovative than Saburo Murakami’s rubbing of garlic on the inside of an envelope to fellow Gutai member TsurukoYamazaki in 1958.

By 1962, Gutai was sending out sets of nengajo to their international following. Gutai nengajo elicited great excitement from foreign correspondents receiving them. Gordon Bailey Washburn, director of the Carnegie Institute, wrote that, “I have been enchanted to receive the New Year’s greetings from the Gutai Group. It is, I think, the most unique message I ever received, and I will keep them all in a portfolio of special Christmas cards as I hope someday to have a little exhibition of such material.” David Anderson, son of New York gallerist Martha Jackson, commented that upon receiving his sent of nengajo, “We were so pleased that we mounted all the cards in a small frame, and they are hanging now in our home.” (Many of my quotations are taken from Ming Tiampo’s, Gutai: Decentering Modernism, University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Gutai’s distribution of creative nengajo was so successful that they expanded the practice to a wider public at their art exhibitions. The same year they sent out their sets of nengajo to Washburn and Anderson, they installed a plastic and aluminum Gutai Card Box during the course of the 11th Gutai Art Exhibition. Visitors to the exhibition were able to insert modest amounts of coinage into the enlarged mailbox and receive a hand painted postcard by one of the Gutai artists. This was not done mechanically, rather the exchange was made by one of the members, who sat inside the box. The work was a continuation of Gutai policy to include exhibition attendees in participatory actions, a mainstay of Gutai presentations over the years.

Other strategies were employed by Gutai artists to overcome their distance from the perceived centers of art. A discarded proposal by Akira Kanayama for the 1965 Nul exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam was a drawing of a mailbox (labeled “post” in English) with an outstretched hand holding a letter. Although similar in conception to the Gutai Card Box, Kanayama’s proposed work stressed instead the presence of the artist in the act of international communication with an unknown audience.

Gutai’s use of the postal system began with the distribution of Gutai magazine, built upon the model of Ray Johnson mailings and incorporated into their participatory exhibition activities. It indicated that the postal system was not only a distribution system for international information, but could be used for the direct transfer of artistic energy from one individual to another, both directly through the mail and by using the postal system as a model representing information transfer in exhibitions. These lessons did not dissipate after the disbanding of Gutai in 1972 following the death of Yoshihara, but continued and expanded, as we will later see in the post-Gutai years of Shozo Shimamoto.

Ray Johnson’s impact on the international avant-garde was not confined to Gutai artists. His influence on Fluxus was widespread. Mailings as creative promotion, new artistic genres based on associated postal mediums, such as rubber and postal stamps, and the blending of art within the everyday tasks of life, were just some of the directions Ray Johnson guided Fluxus.

Fluxus was the brainchild of artistic impresario George Maciunas, an architecturally trained Lithuanian residing in New York. The name “Fluxus” was first conceptualized as the title of a magazine (as was Gutai) by Maciunas, who had opened AG Gallery in 1961, one year before the official start of Fluxus.

Tellingly, the first series of performances presented at AG Gallery included an action by Ray Johnson, who in reaction to the current craze of “happenings” sweeping New York, staged a “nothing” on July 30, 1961. The following year, Fluxus, as a group, was initiated with a series of avant-garde concerts in Germany. The cast and crew of Fluxus were decidedly international, the magazines and newsletters produced by Maciunas a necessity in keeping the informal membership informed.

Among the international artists connected with Fluxus were several Japanese artists including Yoko Ono and her first husband musician Toshi Ichiyanagi, composer Takehisa Kosugi, inter-media violinist Yasunao Tone, Ay-O, Mieko (Chieko) Shiomi, video artist Shigeko Kubota, and Yoshimasa Wada, who became an assistant to Maciunas in his later years.

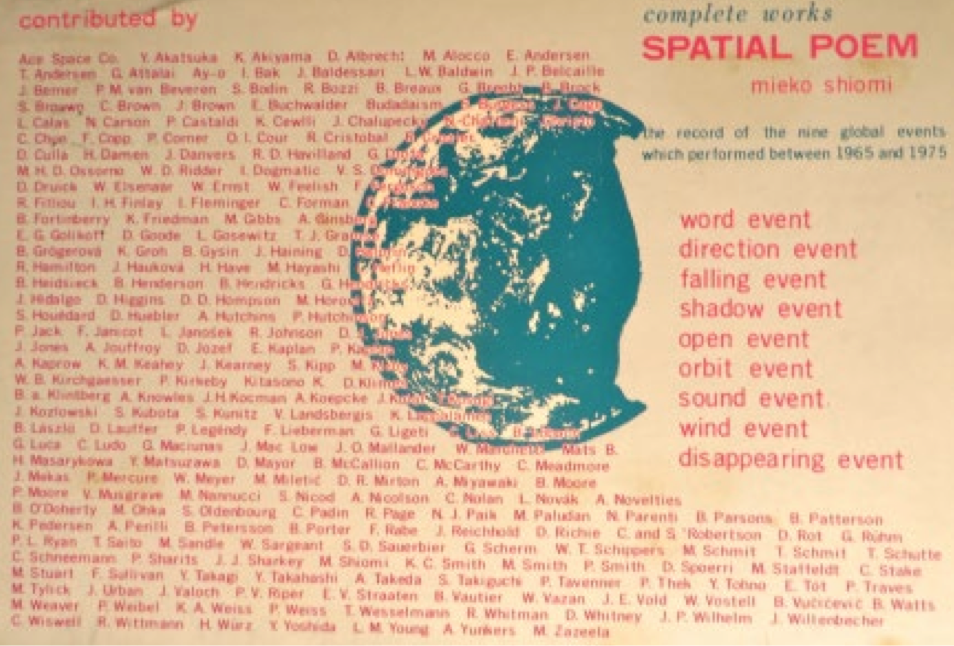

Osaka-based artist Mieko Shiomi is particularly important as a postal artist. She studied music in Tokyo and came into contact with Nam June Paik, who referred her to George Maciunas. She traveled to New York, where she secured work with Joe Jonas, a Fluxus musician. Soon after her return to Japan in 1965, she began her Spatial Poem project, which was composed of nine international events continued over a decade. She extended an invitation to artists from around the world, through the postal system, requesting they conceptualize and stage an event based on a theme and send her the results. The actions would then be charted on a map and sent out as documentation to the participants.

Over four hundred artists participated in the nine events staged over ten years. Among them are pioneers of mail art, who began their practice in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including Ace Space Co. (USA), Peter van Beveren (Holland), Ken Friedman (USA), Irene Dogmatic (USA), Klaus Groh (Germany), J. H. Kocman (Czechoslovakia), Clemente Padin (Uruguay), Chuck Stake (Canada), Patricia Tavenner (USA). Well known artists also participated in Shiomi’s Spatial Poem, including John Baldessari, John Cage, Christo, Allen Ginsberg, Allan Kaprow, Jonas Mekas, La Monte Young—and many of the Fluxus artists.

Japanese artists who participated included Y. Akatsuka, Kuniharu Akiyama, Ay-O, Michio Hayashi, K. Kitsono, Kosugi Takehisa, Shigeko Kubota, H. Masarykowa, Yutaka Matsuzawa, A. Miyawaki, M. Ohka, Takako Saito, Y. Takagi, Yuji Takahashi, Akimichi Takeda, Shuzo Takiguchi, Yasunao Tone, and Yoshie Yoshida. Projects of this type proliferated in mail art over the following years. Some would result in exhibitions, others in publications, some solely documented for contributors. All were based on the premise that a communication network could be used as an artistic tool to aid in the completion of an undertaking possessing contemporary currency on an international scale.

Based on the activities of Ray Johnson and Fluxus, an “eternal network” of artists coming and going, was established and flourished in the post via correspondence, artist periodicals, zines, books using rubber stamps, visual poetry, and other means of artistic mediums marginalized by the mainstream.

One of those “coming and going” was Shozo Shimamoto from the Gutai group. After the demise of Gutai in 1972, Shimamoto joined and then assumed the directorship of an art organization in 1976. Alternatively called “Artists’ Union” or “Art Unidentified,” but generally referred to as AU, the organization provided exhibition possibilities for emerging artists, as well as fellowship for older more established artists, including several who had been members of Gutai. Shimamoto provided a meeting and exhibition space for the group in the same Nishinomiya studio that housed the Gutai printing press. Like Gutai, AU issued a periodical newsletter.

Mieko Shiomi (Osaka, Japan), “Spatial Poem” (Postcard). Offset Print, 1976. Courtesy of private collection.

Although he had known about mail art through his early exposure to Ray Johnson, Shimamoto was reinvigorated by the contemporary manifestation of mail art through Byron Black, a Texas video artist, who had resided previously at Western Front, an alternative space in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, a hotbed of mail art activity in the early to mid-1970s. Black was in Japan to teach English, additionally exposing AU members to the concerns of the international avant-garde, from 1978 through 1984. In a history of AU, it was written that Black had, “an important effect upon mail art and video performance of AU.” After their meeting with Byron Black, “AU” newsletter carried more English language text, expanding its readership to a more international audience.

By the end of the 1970s, Shimamoto was writing a “Letter of Appreciation,” to the participants of the AU organized First International Mail Art Exhibition.

“We are indeed grateful to you for the trouble you had taken and for the most positive cooperation you had extended to us in mailing your mail art work for the Artists’ Union-sponsored First International Mail Art Exhibition held here in September, 1978. Exhibits sent in from a total of 15 countries numbered 380 pieces altogether, giving rise to repercussions in a scale unseen before in Japan.

Your contributions, which doubtless helped to make the first grand international mail art show to be held in Japan a gig success, marking a page in the art history of Japan, are really appreciated.

In the past, mail art shows held in Japan have all been very much individual-oriented or have failed to go beyond or break the boundary of an individual performance.

In the future, we are determined to strive to keep up our work, playing the role of the cog in the wheel of Japan’s mail art works, and therefore, we do hope that you will kindly extend your cooperation in similar exhibitions to be held from now on.”

AU went on to organize many more mail art exhibitions, including one that challenged contributors to send unusual items through the post. The 1986 exhibition was written about in the English language Japan Times, with the title, “Mail an Octopus with Stamps on its Head.”

By 1982, when AU’s, Mail Art Book 1, was published, the group had accumulated an archive of three thousand artists from fifty different countries. Two additional mail art books were published, reproducing works from global sources. In a “network manifesto” issued by AU in 1984, they wrote:

“In Japan the supply of information concerning art is awfully limited. Publication, for instance, is nothing but a business deal with a concrete target for the benefit of (the) majority . . . mail art Network ensures the easy flow of ideas not tied down to economic pursuit beyond the borders of nations . . . We make sure that Mail ART NETWORK is the only way through which you are able to liberate art from any type of authority with a conviction: there is no room for the authoritative influence here. Mail ART NETWORK could be a Renaissance in the coming twenty first century . . .”

AU newsletter and membership would serve as the major information source about mail art in Japan for the next several decades, but as Shimamoto noted, there had been prior “individual-orientated” mail artists in Japan, who had failed to go beyond “individual performance.” Mieko (Chieko) Shiomi was one such individual. Another was On Kawara.

On Kawara was born in 1933, graduated from high school in 1951 and moved to Tokyo, exhibiting in the Yomiuri Independent Exhibitions, as did many members of Gutai. In 1965, he relocated to New York, but conducted a life of global meandering. For over four decades, he began to record his daily activities in paintings, drawings, books . . . and postcards. His date paintings (known as the Today series) mark the passage of time and the artist’s attempt to document and find his place within it. Nowhere is this better exemplified then in various series of postcards and telegrams marking his daily activities. Postcard series in this vein include, I Went and I Met, accompanied by a telegram series, I Am Still Alive.

On Kawara’s most prolonged series were the postcard mailings under the rubric, “I Got Up,” conducted from 1968 through 1979. Each morning during this time period, On Kawara would mail out two touristic postcards from the city he was staying in, rubber stamping the time he awoke in the morning, the date, the place of residence and the name and address of the receiver. The duration of his correspondence with an individual consisted of a single sending to month long multiple mailings. This provided the artist with some consistency while engaged in international travel. In 1973, he sent postcards from twenty-eight different cities.

His periodically posted postcards ideally documented the mail art experience, each postcard authenticated by a cancellation stamp chronicling date and time. The Japanese artist was not alone in his attempt to mark time and his passage through it through the use of posted cards. California conceptualist, Eleanor Antin, was pursing a similar aim in her 100 Boots, project, which documented the march of rubber boots in various locations throughout the United States, ending at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. On Kawara’s project was a more personal one, tracking his own passage rather than a material object through time and space. The conception of the project precedes the Internet as a social connector. Mail art anticipated digital social media—a global yearning for cheap and efficient international interconnection—decades before the Internet.

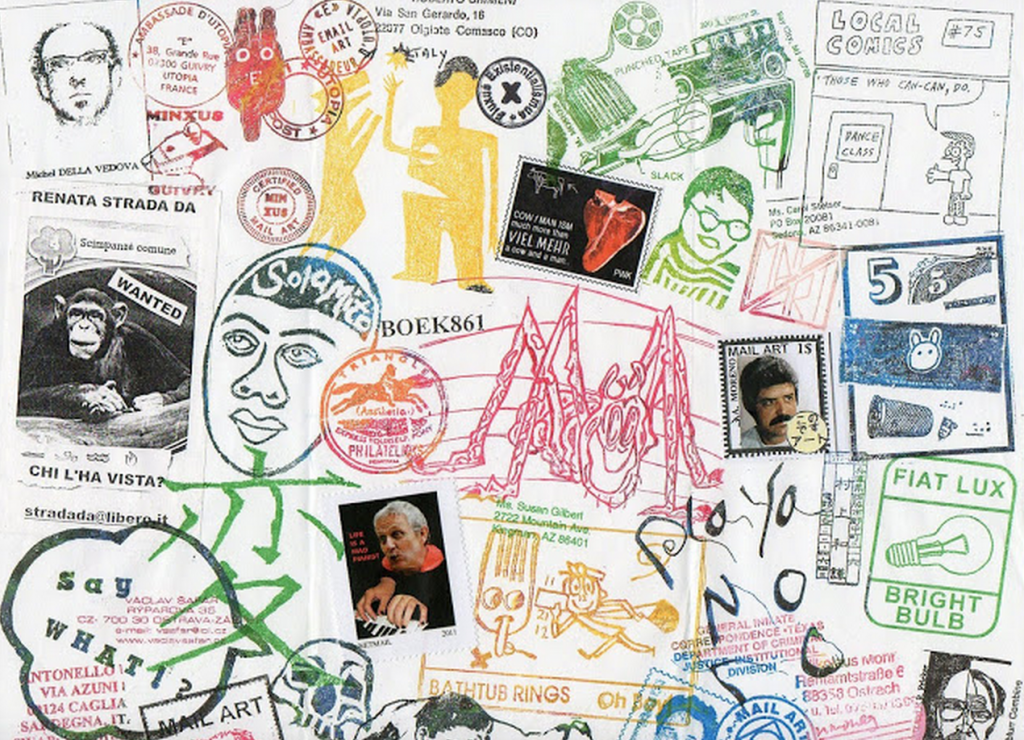

Mail art in Japan during the 1980s was centered in the activities of AU in Osaka, and no member was more engaged than Ryosuke Cohen. The elementary school teacher had been involved with AU since 1979, when he performed a number of conceptual works, such as his message on the side of a truck, which read, “Help me. This is my art. Tell me where you saw it,” accompanied by his address and phone number. At that time the artist was spelling his name Kohen, but Byron Black, jokester par excellence, upon his arrival in 1978, dubbed him Cohen, suggesting a Jewish appellation.

By the mid-eighties, Ryosuke Cohen’s conceptual art activities were subsumed into his mail art works. One of the outstanding and longest lasting projects in the mail art network, Ryosuke Cohen began using a common Japanese printing method, Gocco printing, to gather images from an international array of artists involved in the mail art network. Gocco printing is used in Japanese households to make handmade greeting cards and other family announcements. It has the appearance of color photocopy, but the colors achieve a subtle graduation, rarely seen in Western printmaking techniques.

Previous to creating the numbered units in the Brain Cell series, Cohen used the Gocco printing method on postcards (often with the word “Cell” incorporated in the design), and then began producing sheets with images, usually of his own design. It was but one step to the more formal Brain Cell series, where instead of using his own imagery, Cohen began collaging the graphic work of others received through correspondence. In addition to the Gocco printed sheet of graphic images, a second black and white photocopy sheet listing the names and addresses of contributors, appeared as a second enclosure. This listing of contributors not only stimulated unprecedented interaction between Cohen’s correspondents, but has produced the finest road map of international mail art networking activity over a thirty year period. To date (April 2014), Cohen has issued 887 Brain Cell units. The latest unit included work of fifty-six contributors from eighteen countries.

In addition to his correspondence, Ryosuke Cohen is also a renowned mail art “tourist,” traveling to meet his many correspondents. This has resulted in a new project that has him piecing together his Brain Cell units into large rolls that can be transported when meeting correspondents. Once they meet, Ryosuke has his correspondents lie down on the collated Brain Cell sheets and then traces around them. Using sumi ink, he paints in the background, allowing the body’s silhouette to emerge. This project exemplifies, as well as any, the extension of the mail art experience into real time and space through prior long distance mediated communication. He writes of his penchant for mail art “tourism” in the following:

“I also had opportunities to make tours and meet many mail artists when I visited Europe (1987), North America (1989), and again Europe (1990). Then I was able to sense the trend of mail art and its creators’ multiple situations. I had a very different experience, because at home I usually occupy myself at making and arranging art pieces, and learned a lot through fellowship with other artists. Some mail artists live a very natural way of life, others were very sensitive to peace in the world. And there were those who were willing to realize their art pieces to their utmost. All of them were not free from financial and political problems nor to postal communication, but they overcame those problems and remain with a very positive attitude. I found their attitude really different from that of Japanese. Tourism, I discovered through my experience, has the potential to stimulate looking at the world with aesthetic eyes. It is not just for making a trip and sightseeing.”

This article has only touched the surface in noting the attempts of Japanese mail artists to bridge their geographical divide. Tohei Horiike, from Shimizu-City, curated the exhibition, Art Documentation ’77, in Shizuoka Prefecture, presenting it the following year in Nagoya. Twelve Japanese artists participated, with more than thirty-five contributing artists from abroad. Teruyuki Tsubouchi was active during this period distributing stickers of conceptual road signs. Kazunori Murakami is an active mail artist and a frequent contributor on Facebook. Mayumi Handa has done a number of mail art exhibitions on the subject of hair, and was a performance partner with Shozo Shimamoto.

A number of Japanese mail artists have edited periodicals that have been distributed throughout the mail art network. These include Eiichi Matsuhashi (Great Adventure of Kan- zan and Jyuttoku), Gianni Simone (Kairan: mail art Forum), Kazuyoshi Takashi Tateno (Mail Art Paper and Aerial Print), Shigeru Nakayama (Shigeru Magazine), Yayoi Yoshitome (editor for AU).

“Collaborations By,” edited by Keiichi Nakamura, follows in the mail art tradition of “add and return.” His series of collaborative visual poetry booklets, results from his asking fellow mail artists to add to the pages of graphics he distributes. Upon return receipt, the pages are photocopied and made into booklets.

Gianni Simone, hailing from Italy, is a long time resident of Tokyo, wed to a Japanese woman. He is a reviewer for international art magazines (including SFAQ). The periodical he edits, Kairan, is one of the more thoughtful periodicals produced in the network, each issue usually of a thematic nature (Mail Art and Money Don’t Mix, Mail Art Interviews, Latin America, Women and Mail Art).

Other frequent Japanese contributors to international mail art projects included Kowa Kato, Shigeru Tamaru, Keiko Takeda, Tamosu Watanabe, Dada Kan, Yoshio Takeda, Eiichi Nishimura, Reika Yamamoto, Fumiko Tatematsu, Hiroshi Saga, Shinoh! Nodera, Seiei Nishimura, Seiko Miyzaki, Loco, Toshinori Saito, Yoshiaki Koyayashi, Kazunori Murikami, Jun Karamitsu, and Masami Akita.

Mail art remains a means of communicating across vast distances, with Japanese artists, geographically isolated, yet keenly aware of Modernist culture, eager to come into solidarity with their contemporaries from abroad. Japanese mail art began in earnest with the Gutai Art Association, continued with participation in Fluxus, and flourished under the leadership of Shozo Shimamoto in AU (Artists Union, Art Unidentified). Japanese mail artists have organized and contributed to mail art exhibitions, edited and published mail art periodicals, and organized mail art projects. Their participation has expanded the geographic and conceptual boundaries of the medium, exporting a unique sensibility into global culture.

Other cultures have imparted their own distinctive brand on the mail art experience. No- where is this more apparent than in Latin America, where political repression in the dark years of dictatorships, disappearances and deportations, spurned subtle and not so subtle political activism through the post, often resulting in imprisonment and torture. We trace this history in the following issue.