Phong Bui

Interviewed by Constance Lewallen

This interview has been pulled from SFAQ print issue 17.

Phong Bui is an artist, independent curator, and educator as well as the founder, publisher, and editor-in-chief of The Brooklyn Rail, a free monthly journal of arts, culture, and politics throughout New York City and beyond. It has received many awards, most recently the 2014 International Association of Art Critics (AICA) award for Best Art Reporting. Started as a broadsheet in 1998, the Rail became a full-format publication in 2000 under the direction of Phong Bui and former editor Theodore Hamm. Like SFAQ, the Rail is distributed free (in print and online) to museums, bookstores, universities, colleges, galleries, cafes, and other cultural venues.

I want to start by asking you some questions about your background. You were born in Hue, Vietnam, is that right?

Yes, in the imperial capital of the Nguyen dynasty.

Your family was professional and highly educated, but with divided loyalties, in terms of the politics of the time: the nationalists and the communists correct?

Yes.

From what I’ve read it seems your paternal grandmother had a profound influence on you. Tell me why she was so important to you.

Because she suffered a great deal in her life. She came from a less prominent family than my grandfather’s. As the result, when she was married to my grandfather, her in-laws looked down on her. I will never forget all the horrifying stories she told me about how they completely dismissed and abused her. They made it difficult for her to be with my grandfather. I should mention that it was customary in Vietnam in the past—no longer now, thank God—that when a woman married she had to prove she was worthy of marrying into his family. Basically, she had to live with her in-laws for at least two years to serve them, which included washing their feet, fetching their tea, making their dinner, and so on.

To show respect.

Yes, however, she decided to break the cycle. She vowed never to mistreat any of the women who married her eight sons.

Oh, good for her.

She eventually became a favorite of everyone in the family, men and women, her children, sons-in-law, daughters-in-law, endless grandchildren—everyone admired her, and she was regarded as a compassionate and wise woman to whom people in the town came for advice. I was her favorite grandson, partly because I think she appreciated that I was different from her other grandchildren. I was a bit naughty, and I got excited about all kinds of thing very easily. I would draw battle scenes with colored chalk on the floor of the living room, and she would indulge me with the pleasure of showing off my drawings to her friends.

Did your family live together with her?

No, only I did, in the summer.

I read some of her aphorisms, such as, “When you grow up you will suffer like everyone else but make sure you suffer in the right way.” This one I like even better, “If one lives in a long tube, be thin. If one lives in a barrel, be round,” which is about accommodating yourself to whatever situation you find yourself in, correct?

Yes.

That’s useful advice for anybody. In your particular situation, it was extremely appropriate, because of what your family had to go through— being sent into the countryside to a re-education center. How old were you then?

Around twelve. It was at the end of 1976 or the beginning of 1977, and we were there until the beginning of 1979.

You worked in the fields?

The communist party gave us a small piece of land in the middle of nowhere in the deep delta area; the idea was to punish us, forcing us to live off the land. None of us knew how to farm; we had no farming experience. There was no running water or electricity. We had to build a house out of bamboo, dry leaves, and clay.

Phong Bui, “To Ho Chi Minh City with Love: A Social Sculpture,” 2011. Image courtesy of the artist and Sàn Art, Saigon, Vietnam.

Did you have to grow your own food?

Yes, but we were fortunate enough to have distant relatives who lived in the countryside who my grandmother called upon to live with us, showing us how to cope with the land until we were stable. It actually turned out to be quite a beneficial situation, because since we were in the middle of nowhere, there was virtually no surveillance by local police.

So, you had a certain freedom.

Exactly. My mother would take the bus to Cai Mau, a nearby city, to look for her ethnic Chinese friends who she used to do business with. The government was ousting ethnic Chinese at the time due to the Sino-Vietnamese Border War in early 1979. We were able to obtain false documents identifying us as Chinese and paid off a family of a local fisherman to transport us, seventy of us in total.

In other words, you traveled as ethnic Chinese?

Yes, we paid off local policemen to allow us to leave in the middle of the night, but once we were in the sea, if the coastguard caught us we would have been sent to prison.

Where did you all go?

We had heard horror stories about Thai pirates killing the men and the children, raping the women, stealing everything, so instead of going to Thailand, we took a longer trip to Malaysia.

And then what happened?

We landed in Malaysia where we were held in an area on the beach enclosed by barbed wire for a good four months.

Were you able to escape?

Not at all! There were guards all around us constantly. The days were very hot and the nights very cold, but they provided us with food and water. There was a girl of my age who one night snuck in and asked us whether we would like to send a telegram to our family so they knew where we were, which we did. We sent a telegram to my aunt and her husband who was a high-raking official at the American Embassy in Bangkok. Luckily, they came with several members of the United Nations Commission for Refugees on a helicopter the very next day, just hours before the Malaysian officials were going to load us on boats and push us back out to sea. In any case, we soon ended up at an official refugee camp where we spent another four months.

Eight months all together.

Yes.

And then where did you go after that?

To Bucks County.

[Laughs]. Pennsylvania? Why?

Because my aunt and my uncles lived there. One was in Langhorne, and the other in Bensalem, both in Bucks County.

It must have been quite a culture shock, landing in the middle of Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

Yes. I actually did write about this in an essay which was supposed to be titled, The Restless Artists in the Age of Retirement, not, The Retiring Artist, which was published in the March 2014 issue of Art in America in reference to Jonas Mekas and the state of older artists in the art world. The essay is about how this culture consumes and feeds on youth energy and neglects the elderly. When we arrived in Bucks County I was shocked the first time we were taken to a shopping mall, because I saw that old people were dressed like teenagers. You know, with t-shirts, socks, white sneakers, and baseball caps. We were shocked, but my parents were really horrified, because in our culture, you can’t wait to get old.

When you will be respected for your wisdom.

It’s the opposite here.

Did you study art in Pennsylvania?

Yes, I went to Philadelphia College of Art, now called University of the Arts, because it was in Philadelphia.

Phong Bui, “No, #2 (Homage to Whistler),” 2012. Gouache, watercolor, oil crayon, white out, with collage element, 16.75″ x 23.25″.

I understand that your first ambition was to be an art director or commercial artist.

Yes, I wanted to work for Condé Nast. I was already aware of the legendary Alexander Liberman who I admired, because he seemed to be so worldly and lived such an interesting life. He was the art director for Vogue magazine, which I had seen as a kid in Vietnam. I learned later in college that he was also an artist who made large abstract/geometric sculpture. In my freshman year I discovered Liberman’s great book, The Artist in his Studio, which reconfirmed my ambition. I spent a lot of time in the library looking through all sorts of magazines and journals. However, I took a painting 101 class of with a painter named Jane Piper who was the studio assistant of Arthur B. Carles when she was young.

The American Modernist.

Yes! And his daughter was Mercedes Matter, the founder of the New York Studio School on Eighth Street in Greenwich Village.

So, that became your bridge to New York.

Yes. I remember distinctly when Jane said, “You have set your mind to be an art director, but you have the temperament of an artist. If you ever change your mind, let me know.” That’s what happened. I had been a very good student and won the first prize in illustration and ideas in the senior thesis show. After graduating, I went to New York and had an appointment with Hallmark Cards. They offered me a job right away and even flew me out to see their headquarters in Kansas City.

You could have ended up in Kansas City working for Hallmark. [Laughs.]

Thank God I didn’t do that! But it was at the MoMA that I saw paintings for first time, just alone, that made all the difference.

You must have visited the Philadelphia museum.

I had been to the Philadelphia museum, but at that point I was set on being an art director and nothing else; I was like a horse with blinders. At the MoMA I saw de Kooning’s Woman I, and it really gave me a shock; I got goose bumps. I had just read James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Joyce talks about epiphany. Not the profound, religious sort, but the kind of awareness and free reception of everyday events, insignificant events, that somehow pushes you to some other direction in your life. I went down to the payphone and called Jane and said, “You’re right. I have the temperament of an artist. I want to be an artist. What do I do?” And she said I should go to the New York Studio School.

And you did.

Yes. I was there for two years.

There you studied drawing and painting and—

I studied drawing from life for the first year with Nicolas Carone, who I became close with. In addition to being a painter he also worked for Eleanor Ward at the Stable Gallery. Nic was the one who recommended artists like Joseph Cornell, and Cy Twombly, among others, to her. Nic lived next door to Jackson Pollock in Southampton, and was also very close to the gallerist Alexander Iolas.

Phong Bui, “Portrait of Fran Lebowitz,” March 2014. Pencil on paper, 11×15 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Well, I loved hearing you talk about when Mercedes started erasing one of your drawings, [laughter] you said, “Look, we see things differently. You’re five feet eleven inches and I’m five foot two inches.

Yes, exactly.

And she didn’t respond well to that?

No, she didn’t. I knew that I had come to New York to experience the many great things the city has to offer so I ended up spending time, especially on the weekends, going to see contemporary shows at galleries, and museums, as well as reading about art and literature.

You began to educate yourself.

Yes, I had to.

How old were you then?

I had just turned 20.

What an experience! Did you have friends in New York or family?

None. But I was able to create a group of new friends who were very supportive of what I was doing at the time. But deep down inside I had the feeling that the world was bigger than the walls surrounding the school. It took me years to accept my ambition and to understand that I had potential that I needed to fulfill. I needed to be with equally driven people, to be nurtured and to grow along with them. I keep telling all these young people who are working with me at the Rail now, “If you ever experience any negative comments among your immediate friends, who might make you feel bad for something that you’re excited about, you have to have the courage to move on. Never let them hold you back with guilt.”

I know you knew Meyer Schapiro, and his wife, Lillian Milgram, with whom you forged a close relationship—Schapiro became your mentor. Yes, I became their adopted Jewish grandson. [Laughter].

You met him when you had gone to their home to deliver or pick up a package? Yes, there was a show of founding faculty members at the school that included Nic Carone, George Spaventa, Peter Agostini, George McNeil, Charles Cajori, and few others. Alex Katz was one of them, too, and Philip Guston. Among the lecturers was Meyer Schapiro. Later, Meyer told me that he only gave four lectures there, but his name was associated with the school nonetheless. Meyer would paint, draw, and make sculptures whenever he could, especially when he and Lillian spent summers in Vermont. Anyway, I was told to go to his house to fetch a painting. He asked me where I came from and I said that I was from Hue, and before I knew it, he told me the history of Hue.

And he was accurate?

Oh, yes. There were two people who knew about Vietnam better than I did. One was Meyer and the other was Leon Golub.

I didn’t know that Meyer painted.

I think he could have been an artist, but that wasn’t his calling.

He made art for his own pleasure?

Yes, for two reasons: one was for pleasure and the other was to inform his writing.

You had a kind of informal and private education from Schapiro.

I visited every Wednesday at 4 pm. We would walk for 15 minutes around two or three blocks and then come back home. By 4:30, dinner was served. Most of the time I would ask about his community of friends, such as Saul Bellow, Delmore Schwartz, Elizabeth Hardwick, Irving Howe, among others from the Partisan Review crowd, and also which books I should read, and so on.

Was their home up near Columbia University where he went to school and taught all of his professional life?

No, it was on West 4th Street, between Perry and North 11th in the West Village.

You seemed to have had a wonderful relationship, like father and son, and I know that you briefly considered becoming an art historian.

Yes, I was offered an opportunity to go to graduate school in art history at Columbia, but the same year, 1987, I was offered a grant to travel in Italy where I had never been, and I accepted the grant instead. I stayed with Nic Carone and met Piero Dorazio, Beverly Pepper, Al Held, Barbara Rose, and a whole host of others.

In Todi, in Umbria.

Exactly. And then Nic encouraged me to go to Tarquinia and visit Matta, which I did. Matta had turned a beautiful convent into a studio and living quarters. I stayed with him for a weekend, and he introduced me to other people. It was a great trip; I was there for a good two months.

What an experience!

Yes, it was great. I also met Cy Twombly that summer. That’s when I realized I would much prefer being an artist than living a life as a scholar. I knew that Meyer had encouraged many of his students who he knew were not going to be great scholars to make art instead. The list is long––beginning with Ad Reinhardt and Robert Motherwell, then continuing with Lucas Samaras, Allan Kaprow, Donald Judd, and many others. He definitely saw that they didn’t possess the monastic temperament to be a great scholar either. I remember calling Meyer long distance as well as writing him a letter, informing him that I wanted to be an artist.

Editorial meeting at the Rail Editorial Room with Guest Art Editor Joachim Pissarro (March 2014). Dorothea Rockburne, David Carrier, among others, in the audience.

How did the Rail start?

It started as and 8 x 11-inch sheet of paper, folded it in half with four columns for four articles. Williamsburg, Brooklyn, was full of excitement then. There were endless openings every weekend, but it lacked a critical voice.

Were you living in Williamsburg?

No, Greenpoint. I’ve lived here mostly since 1992. At one point I lived in the East Village, and came here to work. But anyway, Connie, it happened so fast, the whole Williamsburg scene. There was a need for a forum, which would allow different voices to be heard, instead of arguing in a bar, which we used to do a lot. I found it very irritating, because students of specific, specialized fields were completely ignorant about other things.

So you saw a need for a vehicle through which there would be an exchange of ideas.

Yes. Things would become habitual very easily if there were no intellectual stimulation.

Where did the name The Brooklyn Rail come from?

Emily DeVoti, our theater editor, initially named it, because of the L train. Rail also means to rail against something, which has a leftist connotation. Rail is also the name of a bird, which I wasn’t aware of until Henry Luce III, in 2004, wrote me a nice letter after our first meeting and said, “The rail is also a bird; therefore it’s fitting since he could be looked at as a successor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.”

That’s nice. You started the Rail in 1998?

Yes, as a bi-weekly pamphlet with Ted Hamm, Patrick Walsh, Joe Maggio, Emily DeVoti about two weeks before I joined in as an art critic. In those days I would hand it out to people who went to work on the L train, 10 people a day, or so. In the summer of 2000, I sold a painting for 2,000 bucks to support the Rail because I thought if I was going to be involved in a serious way it had to be a real paper.

You were making your own art all this time?

I was making my own art, painting and site-specific installation, and I was showing quite regularly.

To summarize, your aim was to create an intellectual community through a publication by inviting people from many different disciplines to contribute criticism, essays, interviews, etc. I am amazed that you can live and work in the same place where the Rail is produced.

When I was growing up in Vietnam, I can’t remember a dinner with only family. There were always people coming in and out. Our family is extremely sociable.

It felt natural.

Yes. People sometimes even sleep here if they need to.

Do you see the Rail as a constantly evolving journal?

Yes. It’s challenging to keep it alive as a work of art, a living organism as opposed to operating it as a business entity.

It certainly offers you the freedom to be experimental—perhaps because you didn’t know any better.

Well, it’s not that I don’t know better; it’s that I appreciate failure. I know the value of it. I am a close reader of romantic or idealist philosophy. I read Fichte, Schiller, Goethe, Herder, Shelley, Kant—

You just named Western philosophers who are important to you, but, although you are Asian, you haven’t mentioned Buddhism or Taoism.

I grew up in Vietnam as a Buddhist. I was raised with a Confucian moral and ethic, but was educated by the French Lycée system, so naturally I was well versed in European culture. I went to the national school Quoc Hoc, where Ho Chi Minh, Vo Nguyen Giap, To Huu, and other intellectuals had gone. But in the end it is what you make yourself. I like what Beckett once said, “I preferred to live in France during wartime than Ireland in peace.” I think that sense of dislocation, not having a real home can be devastating to some, but it can also be very productive to others who know how to turn that sense of ambivalence—which can be a source of anxiety—into something that can produce serious energy. When I was a kid I asked my grandmother why Buddha left his family because I was sure his wife and children weren’t too happy. She said that he did it for other reasons, which were more important than being the prince, and he took a risk doing it. And no one ever accused him of being a bad father.

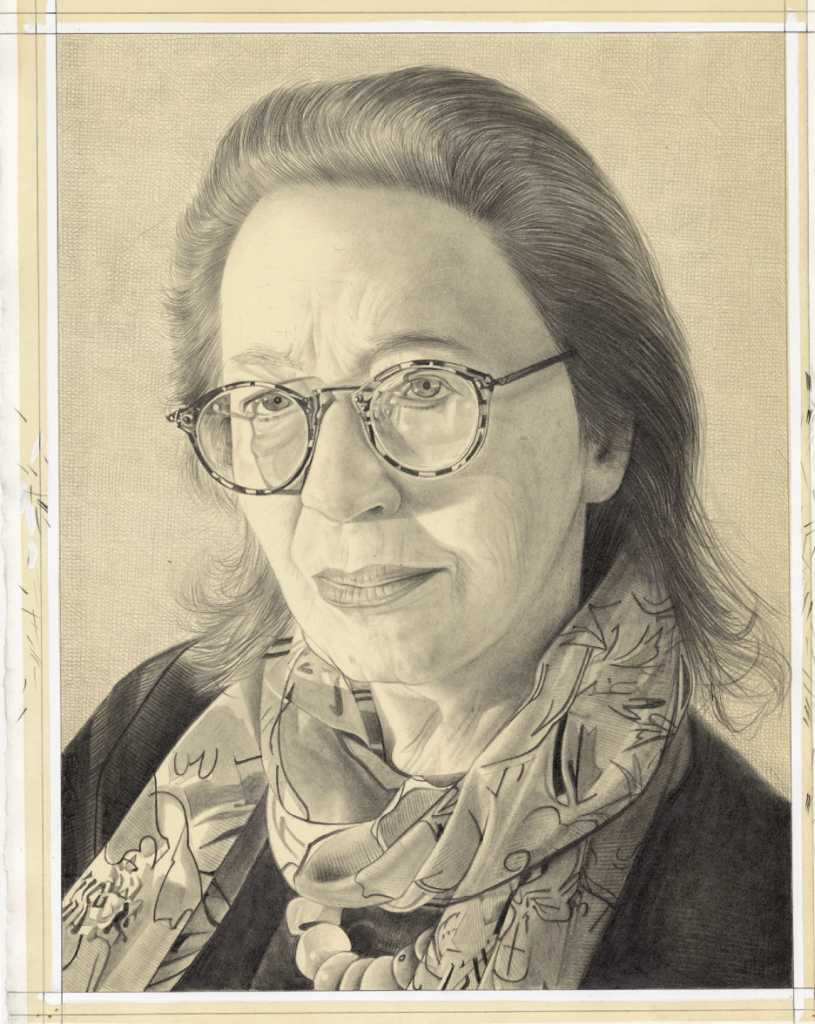

Phong Bui, “Portrait of Elizabeth C. Baker,” 2014. Pencil on paper, 11×15 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Or husband.

William Blake thought of the religious figures like Buddha, Christ, and Mohammed as artists.

In your opinion, how does art relate to politics or specific cultural conditions?

The function of art is to open up limitations resulting from social and political conditions. A good example is Ai Weiwei. I truly believed that Weiwei would not have become Ai Weiwei had he not been living in New York [from 1981–92] observing the New York art world, Warhol, the explosion of Neo-Expressionism in the 1980s, among other inflated situations. But it was the Tiananmen Square episode, which was an Old Testament image, I mean David against Goliath that gave him the permission to do what he has done.

Do you admire him?

I do because what he’s been doing was born out of inner necessity. It didn’t come from the need to survive, which can be an insult to one’s dignity—because if I want to have a good life, for example, in a material sense, I would have become a banker or a lawyer.

Or even an art director.

Yeah, even an art director. But, no, I want to experience the life of a Bohemian.

How do you see yourself now? You’re publishing The Brooklyn Rail, which has recently spawned other Rails in Miami and the Twin Cities. You want to nurture it, to see it grow and change; it’s your baby. But, on the other hand, you’re a working artist, and you’re married to an artist. How do these thing connect?

There are two things that I love about what I do, Connie. One is that it’s mysterious. I don’t always understand all of it. I love this quote from Kant, “From the crooked timber of humanity, nothing ever comes out straight.” Imperfection is something I embrace. Failure, I embrace. I’m not uptight about what people think of me. I have good enough friends, who I talk with about things we care about. My goal is to connect to my inner calling, which I follow wherever it takes me. I’m a conduit of that calling. Sometimes it’s very clear. Some other time it’s not. In fact I am more excited when it’s not clear, because I have to make it clear again. I’d like to think what I do is a Sisyphean labor.

In other words, you don’t want to become complacent.

Absolutely. And the second thing that I came to realize—only from having curated Come Together: Surviving Sandy, Year I last winter—is that everything, from publishing the Rail, curating, sitting on the boards of various foundations where my support can be useful, working with young people at the Rail, teaching, or even cleaning the office at night, cooking dinner for friends, and so on, is treated as an equal part of what I do. Recently, I was re- reading Julien Levy’s book on Gorky, and at some point he wrote, “There are two kinds of artists in this world. Those that work because the spirit is in them and they can’t be silent and those who speak from a conscientious desire to make apparent to others the beauty that has awakened their own admiration.” I’m more inclined to be the latter. I am the fox rather than the hedgehog in the Isaiah Berlin sense. The fox is more accepted in our culture only in recent years.

That’s true.

In my recent interview with Brian O’Doherty, we talked about the success of the Reinhardt show at the David Zwirner gallery, which would never have happened before—I mean showing all aspects of his work, the severe black abstractions, the political cartoons, the slide lectures, all at once. Now, young people are curious. “Oh, Reinhardt can draw cartoons, paint, and write.” I think the bad thing about our globalized culture is that we allow technology to dictate our lives and we have less time for self-reflection. But the good thing is that more boundaries are opened up, even though there will always be some who will resist openness, everything requires new reading, new interpretation. I think this moment is very exciting.

Phong Bui, “Imaginary Interior,” 2000-2012. Gouache, watercolor, oil crayon, white out with collage element, 22 x 12.825″.

Previous contributions by Constance Lewallen include: