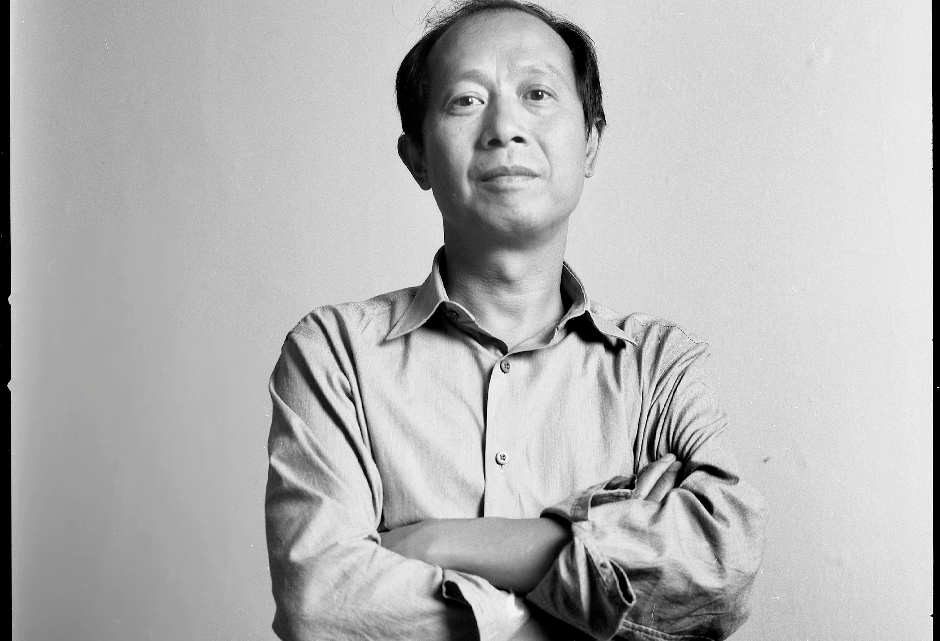

The September issue of SFAQ comes out a month and a half before the third edition of the Asian Contemporary Art Week 2014 (ACAW) organized by the Asian Contemporary Art Consortium (ACAC) San Francisco from September 20th-28th, 2014. This weeklong series of events gathers various local cultural institutions, artists, scholars, curators, writers, and different audiences around Asian contemporary arts and design. Investigating the relations between geography, cultural production, and art criticism from and about Asia, the ACAW 2014 will specifically focus on notions and issues of cultural mis/translations, language, and their philosophies. In the following interview, curator and critic Hou Hanru shared with Xiaoyu Weng, Director of ACAC-SF and Marie Martraire, Program Assistant of ACAW-SF some of his curatorial projects as well as his thoughts on these concepts and the San Francisco art scene.

Since your move from Beijing to Paris in 1990, you have yourself organized or co-organized multiple exhibitions and programs presenting the works by artists from Asia around the world, such as Cities on the Move or Les Parisien(ne)s. How do you approach this process of presenting their works in other socio-cultural contexts? We are particularly interested in the notion of mediation, and translation as the practice of presenting and attempting to render the meaning of a text, an artwork, a cultural reference in another language or socio-cultural context.

First, one needs to understand that Asia is not a unique regional concept, but encompasses different local socio-cultural systems. Each expresses itself through multiple and various ways of engaging with modernity, and hence generating diverse modernities, which are not solely defined by regional, racial, or ethnic considerations. For example, the rapid cultural, economic, political, and urban developments in various Asian countries have provided artists with dynamic and unique contexts for researching, experimentation, and creativity. Numerous Asian artists have investigated this notion of modernity, by re-evoking, revisiting, and reinventing traditions, while struggling against any kind of presumptions of what Asia should be in the West. In most of my work, I am trying to move forward this particular perspective from the point of view of someone struggling against cultural clichés. I insist on the complex history of Asia itself, the unique local contexts and languages, and the different influences that have been excluded by mainstream media and institutions. It’s also extremely important to recognize that all the artists are independent individuals who have their own ways of thinking and doing things, always striving against clichéd readings and appropriations imposed by the dominant powers. Like some artists in Asia, I try to bring these aspects back to the exhibition (or art project) to reflect and negotiate some contemporary issues. Chinese artist Huang Yong Ping is a good example of this approach. His works integrate some classical, but often marginalized, religious and cultural references in Asia, not only China, and bring them back to confront and interpret contemporary events in the West, and in the rest of the world, to predict the future, or “destiny,” of the world. Embracing the idea of cultural hybridity and the tension between the global trend and the individual resistance is key.

Rigo 23, “Autonomous InterGalactic Space Program,” Mixed media installation, work produced in Mexico in collaboration with local artists,2009-12. Part of Zizhiqu, Autonomous Regions at the GuangDong Times Museum.

As a curator, how do you negotiate and promote this cultural hybridity in exhibition making?

I think it is our responsibility as curators to encourage differences by exploring truly inventive ways of exhibition making that foster a trajectory of adventure and keep developing risk- taking. When working on a project, I’m not only trying to work with individuals who are, in my eyes, great artists, but also mobilize their talents and energies to challenge all kinds of established institutional models. For example, Cities on the Move (1997-1999) turned the exhibition space into a real-live city, a place where people could come live, eat, drink, talk, get married, and so on. This exhibition model was inserted into different kinds of Western institutional framework and hence challenged the established model dominated by the white cube as an ideology and a bureaucratic practice. Actually, upon my arrival at San Francisco Art Institute in 2006, I made the decision to not have a white cube gallery. All the walls had to be re-colored according to different projects of the artists, every time, to challenge the pretended “autonomy” of art objects emphasized by the white cube ideology.

The city life and its impact on creative activities have been the central concern for me in my projects, not only Asia. All these aspects put together provided a way to challenge some fundamental Western ideas related to modernity, for example, nations, states, the division of art and other activities, art and science, art and philosophy, etc. So in the end, “Asia” is a concept, a model of operation, a system of value, an aesthetic model more than simply a kind of textual or imagery narrative. “Asia” brings a proposal for difference and hence actions of emancipation. I think what “Asia” can provide us is an incredible dynamic diversity of experiences.

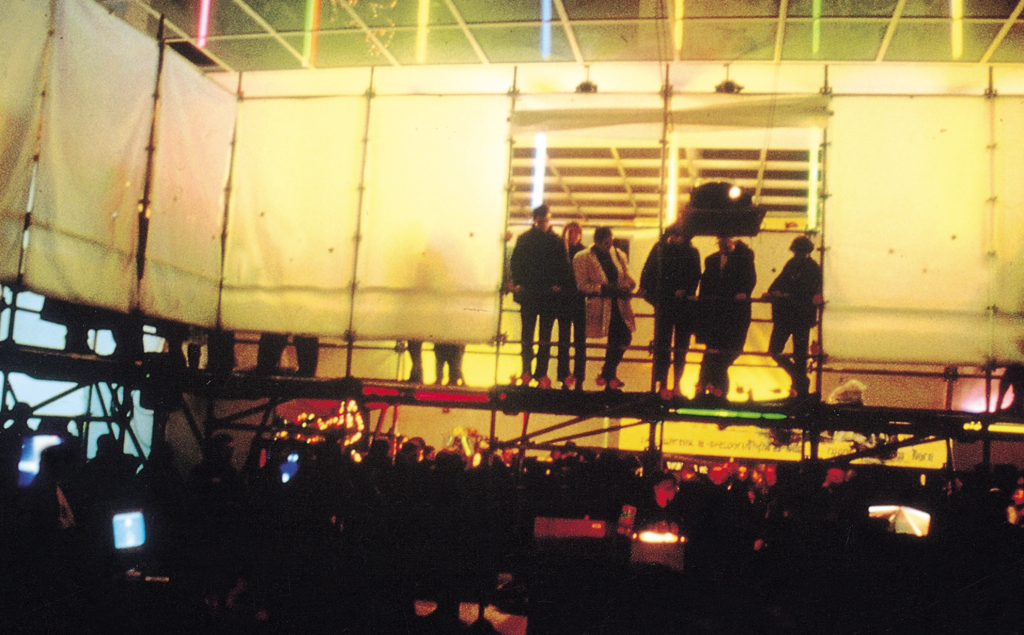

Installation view, Cities on the Move, Secession, Vienna. Curated by Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist.

How does this encouragement of cultural hybridity via exhibitions affect our cultural institutions?

Art is never an academic affair, something that can be framed and defined by any established scholarly system. Asia gathers the most interesting conditions to rethink our cultural institutions and become more subversive by creating different alternative structures to emphasize diversity and variety. This is why I insist so much on using the dynamic of social and economic progress in exhibition making and preventing repetitions. Take, for example, the 2002 Gwangju Biennale in Korea. I decided to invite around thirty independent artist-run organizations to install their spaces in the exhibition spaces, which, in turn, were structured in urban settings including streets and plazas. The invited groups had total freedom to organize different kinds of curatorial projects while their physical architectural structures were reproduced in the city-like exhibition halls. This initiative not only aimed to gather all those organizations together, but it was also a way to tell people that repeating the same models of exhibitions and institutions is not mandatory. The contrary is true . . . For me, the most interesting artworks and artists are those who are working in the street, who are actually in relation with social reality. They call for deconstructing established models of institutions. Unfortunately, because of the phenomenon of globalization, I am observing that more and more Asian artists of the new generation are producing works similar to what we can see in the mainstream Western institutions, schools, markets, and media, or do very standard and academic paintings and objects. I think this is highly problematic.

Huang Yong-Ping, Amerigo Vespucci, 2003, install view Wherever We Go: Art, Identity, Cultures in Transit, 2007, Walter and McBean Galleries. Courtesy of Hou Hanru.

This is probably a big question but we are very curious about it. How do you see your own practice evolve under the broader discourses of globalization in the past 15 years? How do the debates and discussion about globalization, migration, and dislocation evolve? Do these topics still have the urgency and relevance compared to twenty years ago? Do you think it will be interesting to revisit some of the issues you explored in the exhibition Cities on the Move?

My practice attempts to understand the key issues within an art institution. More specifically how a museum should handle today from the perspective of boundaries between political and intimate spaces, the relation between public and private, and the question of geopolitics, migration, and technology.

For instance, in the case of the National Museum of XXI Century Arts (MAXXI) in Rome, how can it remain a center for democratic culture? I am working on bringing together the two museums housed by MAXXI: the MAXXI Arte and MAXXI Architettura. I envision creating multiple directions in the programs and staff of these two museums to encourage dialogues and interactions between art and architecture, to then create a new, common “city life” for the museums. I want to make the museum a democratic space by reconstructing the idea of a Roman forum, i.e., a public space and sphere in which people debate the question of the society. These programs have to have a strong component of public speech. The program Open Museum, Open City will take place next October and November. We will be emptying the whole museum, turning it into a huge empty space, and filling it with sounds. Artists such as Bill Fontana, Ryoji Ikeda, Cevdet Erek, or architects like Philippe Rahm, will develop some performative installations in different parts of the museum. The “show” is invisible but intensive and immersive. The institution will become a city where dialogues amongst different voices unfold over time. A radio will also be broadcasting sound works, including a program of open calls for public participation, both in the space and online. And then, in the afternoons and evenings, the galleries will host various performative events, such as performance, dance, theatre, story-telling, and poem reading, as well as Hyde Park Speaker’s Corner style public speeches. Another project is The Independent, a three-year project devoted to the promotion of national and international independent groups working in the fields of art, architecture, design, dance, and music as well embracing broader areas such as publishing and town planning. In Italy, there is only one national museum for contemporary arts—our museum, the MAXXI—but there are many small independent institutions, often created and run by independent artists, curators, editors, designers, etc., in different cities. In The Independent, we tried to invite those small organizations to come take over the atrium stairways of the museum, the most emblematic part of the iconic building, and to develop experimental programs. So to a great extent we don’t need to go to Asia to have an “Asian show:” a certain Asian way of doing things, a non-Western energy, is being brought into the center of this institution.

Hamra Abbas Love Yourself , 2009, install view Everyday Miracles (Extended), Walter and McBean Galleries. Courtesy of Hou Hanru.

How do you convey to audiences this idea of challenging institutions, encouraging artists’ experimentations through exhibitions?

In terms of making audiences understand what we are doing, first we need to create a context in which they can experience the necessity of change. Then we invite them to be a part of the adventure. Most of the projects I have been doing consist of creating possibilities for public participation while going beyond the institutional model and the cultural context. I not only invite audiences to be a part of the performances, but also, if this is possible, work with the educational and curatorial teams. I try to go into the different suburban communities to generate collaboration projects. For me this is another way to negotiate and break down the borders separating high-culture institutions and diverse members of the society.

Can you give us an example of a project you’ve realized that created a space to negotiate the borders between audiences and institutions, but also between visitors and artists’ works when they are from different socio-cultural contexts?

For example, I worked with Indonesian artist Eko Nugroho for the Lyon Biennale 2009 who was well known for creating spectacular and fantastic graffiti figures. I also knew that he was collaborating with different populations to create shadow theatres, which have a long tradition in Indonesia. I invited Eko to work with kids from the suburbs of Lyon and develop a multimedia theatre piece based on stories by different local families that had immigrated from Africa, North Africa, Europe, and many other different places. After an engagement of six months, the play came to light and was performed in different suburbs. Audiences could see a combination of contemporary technology, music, urban dance, hip-hop, and traditional craft in the shadow puppets’ play. I think the play had an effect on the young people involved with the project. They learned a lot, especially because the play was based on their own stories, their own lives, their cultural roots, their contemporary existence. Another example is the 5th Auckland Triennial that I curated in 2013. A section of the Triennial took place in the suburban area in collaboration with people from Asia, Australia, New Zealand, America, and Europe. Together they produced an incredible program for the local community to talk about their own problems, and create a proposal for transforming their community. This approach was brought back to another group project that I did at the Times Museum, Guangzhou, China, entitled Zizhiqu, Autonomous Regions. We also invited the San Francisco-based muralist, painter, and political artist Rigo 23 to present his project of working with the Zapatista community in Mexico, along with other artists’ projects, to develop a defense of autonomous initiatives to fight against gentrification and the domination of capitalism and political power. Extending his project, Rigo 23 and the museum’s team worked with the local people and activist groups in an area of Guangzhou where gentrification was happening to mount a manifestation. In a general sense, the artistic projects triggered the first step of action, of resistance. Other local art communities adopted the model of the projects to imagine their own. These projects are much more global, but look specifically into a local situations. Similar experiments have carried out in Xinjiang, the Uyghur region of China, the borderline between Israel and Palestine, etc. . .

Installation view, Cities on the Move, Secession, Vienna. Curated by Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist.

The issues of mis/translation, or mediation, between artists and audiences from different socio-cultural contexts might seem key in programs based on social engagement. How do negotiate these aspects?

If we could translate art into other languages, or even into languages, then we wouldn’t need art anymore. The real question is, then, whether or not it is possible to translate a language to another comprehensively? We all know that the process of translation includes a huge proportion of misunderstanding and missed translation. For example, the question of translating what we call “Asian art” in other parts of the world does not simply come down to understanding the artists’ intentions, but rather apprehending and embracing the limits of what art proposes we look at. If not the exact meaning of the work, we can translate a gesture, an action, a process that generates possibilities of sharing various elements, and especially, imaginations and visions, such as what we call “Asia” for example. When looking at artworks by artists from Asia, we are not only grasping the existence of a “different” story behind the work. We are also experiencing a possibility to imagine a world that can only be imagined, shared, and constructed by introducing cultural difference. This process makes us realize that we have been taking for granted the world we usually accept as normal, as the norm. This is why I feel very sad when I see a 25-year-old curator who organizes white cube exhibitions in the most perfect, hence, most closed, way—applying textbook exhibition making à la lettre. Curating is something that should be (re)invented every time. For me, “translating Asian art” into a Western context is about challenging some established values and opening up our minds. Translation is about creating a dynamic around both the possibility and impossibility of understanding each other, which generates a potential for imagination and debate. That is the ultimate meaning of translation: to do new things, we have to question and destabilize the meaning and value of the old ones.

Following this thread of thought, what are your thoughts on the role social medias (including platforms such as Weibo, Facebook, Twitter, and Ama- zon, among others) can play today to challenge institutional models while engaging audiences in art discourses?

Everyone is fantasizing on the role of social media, talking about its potential of developing information. But we are actually facing a new monster, like Godzilla who no one really knows if he is good or bad. Fortunately, their use has become a technological skill to reach some sort of justice and equality. But sometimes, this can also result in a lack of depth of reflection and criticality. Are mediocrity and conformism an inevitable outcome of “democracy?” The worse could be clientelism dominating the model of social communication . . . We are witnessing very complicated consequences of these platforms today, for example in the Arab revolutions in which they played an important role. I believe social medias reflect the fundamental contradiction of the tensions between democracy and populism, which remains an unsolved question despite being discussed since the philosopher Plato. They also create spaces for negotiating these frictions.

Installation view, Cities on the Move, Secession, Vienna. Curated by Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist.

How so?

The potential of social media probably allows us to rethink our institutions, their roles and functions, by shaking up boundaries that may exist between audiences and institutions, artists and institutions, or as mentioned between democracy and populism. For example, social media blur the lines between artists and “ordinary” social media users by bringing another aesthetic, another imagery or textual canon in art. Asian populations, especially young people, embrace the culture of entertainment, and new technology, but they have critical point of views. How, and how much, can institutions adapt to this new relation? It is a very open question for me.

Maybe we can talk now about California, and more specifically the San Francisco Bay Area where you used to live from 2006 to 2013. California is a site with deep geographic and historical connections to Asia, and in 2013, the state claimed the biggest Asian population in the United States. Various art institutions, from larger public and educational institutions (such as colleges, universities, museums and culture centers) to smaller art venues (such as alternative space and galleries) present the arts and cultures of Asia in the San Francisco Bay Area. How would you evaluate the current San Francisco art scene and its presentation of Asian artists?

The San Francisco art scene has a long relationship with what was supposed to be coming from Asia: visual art, literature, music, theater and so on. This relationship has developed through some key historical, political, and economic moments, and thanks to trans-pacific migrations, such as artists traveling through or those now living in the Bay. The Asian Art Museum opened in 1966 and is perhaps one of the few art museums outside of Asia that hold such a large collection devoted exclusively to the arts and cultures of Asia. More recently, other art gallery institutions in the San Francisco Bay Area have been paying increased attention to artists of Asian origin. California College of the Arts, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Chinese Culture Center, and many others, including commercial galleries, have been presenting regularly works by Asian Artists. The Kadist Art Foundation San Francisco is perhaps the most active and intellectually consistent institution that engages the Asian contemporary art scenes. They are developing deep and growing programming, starting with a series of artists-in-residence coming from Asia, building their collection of works by Asian artists, and supporting projects in and outside San Francisco, in different parts of Asia, specifically China. Among a group of individuals, local galleries and institutions in the city, the Asian Contemporary Arts Consortium was set up in 2010, a not-for-profit coalition dedicated to increasing awareness and understanding of Asian contemporary arts and design in the San Francisco Bay Area. Another similar entity already existed in New York City. ACAC San Francisco grows rapidly and is having more and more interesting programs and contributing tremendously to the relevant discourses. You have obviously done a lot of work in this regard.

Has this current dynamic situation changed from the time you used to live in San Francisco, from 2006 to 2013? How would you evaluate the San Francisco art scene and the presentation of Asian artists then?

Many changes took place in the last few years. When I arrived in San Francisco in 2006, audiences and institutions had relatively little knowledge about what’s happening in Asia, and the presence of Asian artists in the Bay Area. While working at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), my programs were devoted to making this younger generation of Asian artists visible in the San Francisco context, and to deepening the formation of cultural identities in these current specific contexts. One of the main programs, entitled Pacific Perspectives, focused on the dynamic scenes of art creation occurring across the Pacific Rim (ranging from the Americas to Asia) and connected San Francisco and its unique geographic, historic, social and cultural connection with Asia. Today, one of the immediate examples is the Kadist Art Foundation San Francisco. The Asian component in their programs has grown so vividly and intensely that it has perhaps become more visible than their San Francisco focus. I even suggested changing the name from San Francisco to simply Pacific! Kadist Pacific sounds great, right?

How would you explain this recent shift of attention to Asia in the San Francisco Bay Area?

I guess for multiple reasons. First, the demographics of San Francisco, with big Asian communities (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Filipino, etc.) have influenced this shift. Each community has developed its own support for artists of the same origins. Some groups of individuals, such as the Chinese Cultural Center of San Francisco (CCC), have made remarkable efforts in this field. CCC’s contemporary art program does not only involve Chinese artists living in America, but also brings more and more artists from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, etc. to the Bay Area. They also organize public interventions in the Chinatown area. Second, numerous educational institutions where many Asian students are now studying on the West Coast, including in art schools such as California College of the Arts and San Francisco Art Institute, focus on contemporary art. Third, maybe artists from Asian origins who live in the Bay Area have perhaps gained more self-confidence. Their activities have become more sophisticated, in terms of intellectual research, collecting, analysis, discussions, and so on. Opportunities to show their works in cultural centers have also opened. Finally, I believe that this recent change is also linked to the way of living in the Bay Area. Social and cultural values are widely influenced by what we call “modernities,” i.e. the complexification of the whole cultural system we are now living in. More and more interactions and exchanges between the San Francisco Bay Area and art scenes in Asia are happening as we are starting to understand the existence of a West Coast identity as part of the Pacific Rim. All of these aspects make us feel that the San Francisco Bay Area is living a really exciting moment. We are really embarking on a much more exciting adventure than in the last decade. So this is the general impression of course.

How do you envision these exchanges across the Pacific Rim—the areas around the rim of the Pacific Ocean?

Today Asia Pacific is perhaps the most dynamic part of the globe from historical, economic, and cultural perspectives. A very interesting relationship exists between different cities across the Pacific, including the entire West Coast of North America, down to Latin America. For example, Vancouver hosts the public gallery Centre A—the Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art—and the magazine Yishu, the first English language journal to focus on Chinese contemporary art and culture. Or the magazine ArtAsiaPacific, an English-language periodical covering contemporary art and culture from Asia, the Pacific and the Middle East is now based in Hong Kong. But it started in Australia, then traveled to New York, and is now in Hong Kong. This trajectory of art knowledge in the Pacific region reveals a potential redefining of what the contemporary world is, and a way to draw new centers on a global map. Kadist Art Foundation is actually currently developing a special program, entitled Kadist Pacific, in which you and Marie are actually playing an essential role. The idea is to explore the connections between California and San Francisco with the other side of the Pacific, from Japan, China, Hong Kong, all the way down to Southeast Asia.

Issues of translation also apply to institutional (museum and gallery, etc.) practice. For example, although funding sources are different, the booming of art museums and galleries in China gives the signals of the desire to have infrastructures of collecting and displaying art. But many of such efforts are simply copy and paste of Western models of museum practices without the consideration of local contexts. What are your views on the museum fever in China?

The development of museum practices in China is in an initial, immature stage today. Hundreds and even thousands of museums are being built today following economic, political, or private interests, such as urban expansion and real estate development. A lot of these new museums don’t even have any curatorial vision or program; they simply have a building, and it then seems immediately natural to copy models they saw in the West or neighboring countries like Japan and Korea. But there are some exceptions, which have been well thought out, prepared and executed. They can be coherent models for the others. The exceptions are interesting for me: you are also witnessing today the emergence of some particular institutions developing interesting models, such as Times Museum in Guangzhou and Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai. These models develop a vision of their institution in relation with the city, architectural and urban conditions, as well as serious considerations on their influences on the local cultural scenes and populations.

Installation view, Cities on the Move, Bangkok, Thailand . Curated by Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist.

How do you see museums evolving in China in the future?

It is difficult to predict the development of art museums in China. Today, there are more and more, bigger and bigger museums, more and more numbers. In a few years, there will be more and more empty buildings. For me, two possibilities exist: build smaller but very well prepared institutions, such as the Rockbund or the Times Museum, or develop gigantic buildings, with crazy design and fancy openings. Because of their non-sustainable model, these latters will have to invent solutions to survive in a nearer future: becoming something else, close down, develop something new out of this condition, and so on. But again, exceptions are possible. One cannot deny there are still some interesting and valuable outcomes to be produced out of this uncontrollable and chaotic commencement. There could be some great museums born out of chaos and the trouble-shooting process. There is always some inspiring stuff being produced out of entropy and monstrousness, like what the Spiral Jetty of Robert Smithson demonstrated . . . this is what I call post-planning. Post-planning is a practice of development inspired by the energy coming from the urban expansion and its problematic consequences. In Asia, especially China, developers take over unoccupied lands to build buildings without proper infrastructures, speculate on the future urban development of their location, sell them, and only after find money to build the roads to connect these spaces between them. Today, urban planning is also about correcting mistakes generated by these excessive urban expansions. Some highly inventive solutions can be found in this process of urban development. They challenge textbook-type urban planning and social programs. The solutions often seem to be irrational but much more pragmatic and adapted to local needs. They open new perspective for further social experiments in terms of economic, cultural and political restructuring and inventions. For example, the functions of a vacant office building can be entirely reinvented: maybe after being abandoned for ten years, one “mad developer” will jump on the opportunity, buy the building for a very cheap price, and then introduce all kinds of new activities such as hotels, shopping malls, restaurants, smuggling, drugs, arts, everything. From an office building, this edifice will become a whole city inside! Imagine if this new re-development follows an aesthetic inspiration. It can be completely fantastic.