At the invitation of SFAQ’s magnificent publisher Andrew McClintock, I have made the following selection from my little book Logro, Fracaso, Aspiración: Tres Intentos de Entender el Arte Contemporáneo [Achievement, Failure, Aspiration: Three Attempts to Understand Contemporary Art], published in 2014 by the Universidad de Los Andes. The book is based upon and closely follows a series of lectures I gave at the Universidad in Bogotá in late February, 2008, at the invitation of my friend and former student, Fernando Uhía. This book and the lectures upon which it is based are part of my philosophical project of understanding contemporary art as a kind of art, something continuous with the rest of the world’s art and something that is not reducible to some other sort of practice or sphere of life, such as economics or politics.

Marcel Duchamp, “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” 1915–1923. Foil, varnish, oil paint, wire. Courtesy of the Internet.

This way of framing the project is polemical. I have always rejected what seems to me to be the two most general assumptions concerning contemporary art. The first of these is that contemporary art is a kind of sui generis phenomenon whose paradigms are a set of works by Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, and some conceptual artists. By contrast I consider these works as, so to speak, conceptually parasitic upon more basic works and practices from which they arise and upon which they play; these more basic works include those of Bertolt Brecht, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Smithson, and Eva Hesse. The second assumption I reject concerns artistic meaning: with most prevailing conceptions of the aim of contemporary art, artistic meaning is treated as reducible without remainder to other kinds of meaning, whether political, social, or therapeutic. By contrast I follow philosophers such as Richard Wollheim and Paul Crowther in thinking that before artworks can take on these other kinds of meanings and functions they must already have a life of their own, one that is created in their irreducibly artistic meanings.

Eva Hesse, “Untitled or Not Yet,” 1996. Cotton, plastic, paper, lead, and string, 71 x 15 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. Collection of SFMOMA. Courtesy of the Internet.

To treat contemporary art as art implies many things, but first of all it means to understand contemporary works as arising from and articulating the three great roots of artistic meaning: representation, expression, and pleasure. Secondly, it means to see the works as part of an irreducible complex that links artistic making (the marking of surfaces and the creation of appearances) and the viewers’ responses. In the first chapter I analyze something of the achievement of William Kentridge as distinctive in contemporary art, and focus, in explicit opposition to what seems to me the most intellectually sophisticated account of this achievement by Rosalind Krauss (as well as implicitly to the standard sub-intellectual, reductivist accounts of the art world’s intelligentsia, such as curator Okwui Enwezor), on Kentridge’s conception of the creative process. On this explication, the creative process in contemporary art, with Kentridge’s conception as one major exemplar, is something bearing multiple powerful and not readily reconcilable imperatives; as marked by contingency, and as expressive of a distinctive political conception. The following is the English language version of pp. 33-37 of the book:

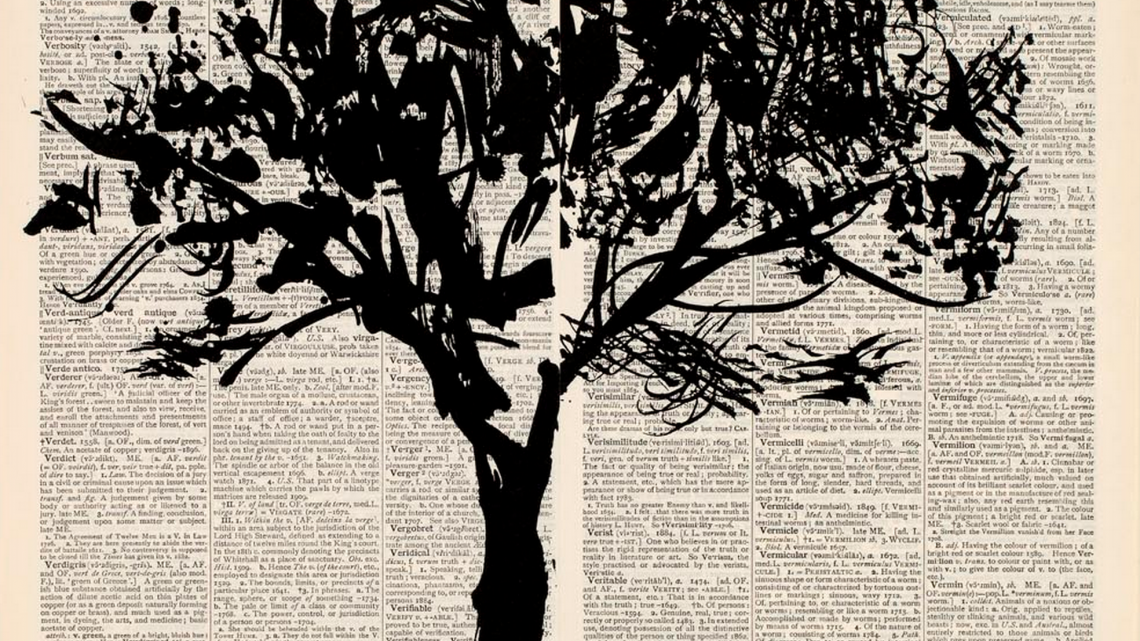

William Kentridge, drawing for “Tide Table,” 2003. Charcoal on paper, 48 x 63 in. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris.

Part 1:

Kentridge makes the creative process central to his account of how his practice gains significance. The work begins with a desire—the desire to draw. This desire is Kentridge’s, and must be thought of as both dispositional and episodic. In its dispositional dimension, the desire to draw has a core expression in Kentridge’s making successive marks upon a surface. Once in place, the desire is given some content by the registration of some contingent event. Once a drawing is initiated, the desire becomes part of a more complex demand, to maintain responsiveness to the world, but also for Kentridge to respond to what is emerging in the marking, and to mark in such a way that marking has no evident terminus.

Kentridge repeatedly characterizes the process of drawing as a passage from knowing to seeing. At its most general, the phrase “from knowing to seeing” suggests a characteristic movement of the mind from grasping something in light of some classificatory concept to the rendering of the qualitative aspects of the phenomenon that are irrelevant to the classification. At this level, Kentridge sounds as if he’s giving a version of Adorno’s negative dialectics as a kind of going through and then passing beyond the concept. But Kentridge puts more stress than Adorno typically does on responsiveness to what is emerging in the very act of making. One might think of Kentridge’s drawing like this: having begun to draw, one has already marked, and the marked surface is seen as bearing a partial responsiveness to a prior situation, but also as having certain dynamics, and certain expressive potentials. Now the drawer monitors the marked surface, “knows it as such,” but then (or perhaps one should say, “then,” as what follows may be experienced simultaneously in the “knowing”) “sees something.” What is “seen” is a potential that needs to be actualized, a dynamism that needs to be extended, or a dissonance that needs resolving, etc. The next mark aims to register that act of seeing. Having been made, the mark alters the immediately prior situation. It now is the sufficient condition of a new situation, with the dynamics of the passage from knowing to seeing ready to be enacted again, monitored by the drawer’s gaze.

Engraved Ochre, from Blombos Cave, South Africa, 4 in long. C. 75,000 B.C.E. Considered the earliest known act of art making.

So far, this drawing of Kentridge’s seems simply accumulative. The need for the erasure of what has been made immediately prior to the marking arises from the more basic need for visibility. Contra Krauss, Kentridge’s work is not a palimpsest, but something more like Penelope’s weaving, with the addition that the undoing remains marked in what is woven. And it is of course the visible erasure, which gives the figures in Kentridge’s films the sense that they are tracing their own pasts, now visible, that are so striking to viewers. This process of visible erasure seems to bear three kinds of primary expressiveness. First, it marks a distinction between Kentridge’s practice and the typical practice of animation, wherein the gap between one rendering and the next is so slight as to escape perception, or when detectable, appears as a jumpiness in the temporal unfolding of the depicted actions. The image carries the Brechtian aura of something made, with some aspect or aspects of its making made explicit. Second, it introduces a sense of the image as bearing marks of its own temporal movements. After the initial presentation of the drawing, the depicted movements seem to carry trails of their most recent past movements and physiognomies. And third, it heightens one’s awareness that the image is something made to some extent by hand. The “crudeness” of the drawing, together with its evident temporal unfolding, highlights the facture of the image. The image is vividly something made by a human hand, monitored by human eyes, and addressed to like eyes.

It is in this third kind of expressiveness that Kentridge sees one aspect of the political significance of the work. He links this with a Brechtian exposure of the device of making. His particular route to this was through earlier work in the puppet theater, when as in Bunraku, the puppet’s handlers were visible. Kentridge refers to this as a double performance—an action is presented, and the making of the action likewise. Unlike Brecht, Kentridge does not make the claim that the exposure of the device somehow “produces” a distanced, reflective, and critical spectator. The effect is rather an “unwilling suspension of disbelief”—disbelief, that is, in the claim that because the action is exposed as a construct and a fiction, it thereby loses its psychologically gripping quality and blocks the viewer’s perceptual and imaginative involvement. The suspension is “unwilling” in the sense that it happens quasi-instinctually in attending to the spectacle. Even though one maintains awareness of the artifactuality of the image, all the same one is drawn into the depicted world.

There are then two ways in which some valuable political dimension might be ascribed to Kentridge’s work. Negatively, one might point to an aspect, one that Kentridge values, of exposing contradictions. As Alain Badiou has put it, every age has its illusions, the exposure of which might be thought of as a broadly cultural task. Positively, one might point to the sense of a kind of memory and “working-through” that the films model.

However, this topical dimension seems unlikely to sustain interest across generations, and may be no more important to the artistic effectiveness of the works than Brecht’s equation of capitalists with gangsters in The Three-Penny Opera. Here it would help to recall something of the claims that have been made for the significance of the fact that artworks are (mostly) embodied in media, and accordingly available to perception. Richard Wollheim has enthusiastically put forth what he unfashionably calls an essentialist account of artistic media. He suggests that there are at least two kinds of judgments made with regard to artworks: judgments of taste, which have to do with whether and to what degree one happens to care for this particular “type” of work, and judgments of interest, which relate to the artist’s uses of the particular medium in which he or she works. One charge that has been made, most notably by Julian Stallabrass, against major strains of contemporary art is the artist’s use of a technique of “one-offs,” where some highly unusual and highly marked material is worked in some non-traditional way(s), and one senses in the seeing of it, however striking the work is, that this way of working has no future; once one has, say, made a “piece” that consists of people running through tires in Central Park, or having oneself dumped on the freeway in a sack, that’s all there is to it. Now, if one judges that that way of working has no future, it also has no present, for the unanswerable question arises of whether there are better and worse ways of doing it. If not, or not in a way that anyone could care about, then the activity cannot be thought of as governed by criteria of success (and failure). If it is not possible to fail, it is not possible to succeed.

John Rapko’s book Logro, Fracaso, Aspiración: Tres Intentos de Entender el Arte Contemporáneo [Achievement, Failure, Aspiration: Three Attempts to Understand Contemporary Art], was published by the Universidad de Los Andes in 2014.