Artists of all nationalities, all creeds, and all backgrounds have discussed the continual movements and redevelopments of diasporas in an aesthetic context. Of these practitioners, one who has emerged as a definitive, contemporary voice of the Vietnamese emigrational population, and of those who call themselves “global citizens,” is Danh Vō (pronounced “Yaan-Voh”). The history of this 39-year-old multidisciplinary artist, garnered from his highly complex installations and individual projects to his own personal background, may be referred to as a tapestry of events, memories, and finely tuned observations taking shape before an equally cultivated audience.

Danh Vō, “July, IV, MDCCLXXVI,” 2011. Installation view at Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany. Courtesy of Isabella Bortolozi Galerie.

Vō’s practice is informed by more than a constant state of migration between politically erected borders, as this would be an all-too-convenient set of circumstances for the artist. He was born in 1975 in the Bà Rịa-Vũng Tàu province of Southeastern Vietnam, and was moved with his family (shortly after the fall of Saigon near the end of April that year) to the Mekong Delta island of Phú Quốc. His family became refugees as they escaped the country in a homemade craft, which was picked up by a Danish Maersk freighter. The Vō family settled permanently in Denmark. The artist’s own name has, too, experienced varying states of movement from his birth name to one including the surnames of his former spouses (his current legal name is read as Trung Ky Danh Vo Rosaco Rasmussen). Destabilization of the body, of the mind, and the blur between them that somehow composes an individual identity is a recurrent motif in Vō’s work, though it is worth noting how his works firmly anchor the viewer into his own backstory. The absence of that biographical fixture would likely result in the viewer having no immediate reference point, no mental springboard from which a meaningful discussion on cultural and psychological migration may be introduced.

Vō began his formal education in painting at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, but ended up completing his studies at Städelschule, Frankfurt, before settling in Berlin in 2005. In 2006, he was a resident at Villa Aurora in Los Angeles, nestled in the Pacific Palisades, alongside Dr. Joseph M. Carrier, Jr. (a distinguished scholar, Marine Corps veteran, and a counterinsurgency specialist who worked for the Rand Corporation during the Vietnam War). Three years later, he was invited to the Kadist Art Foundation in Paris for another four-month residency. His most high-profile public projects have been executed within the last three years: the remnants of a transplanted Vietnamese Catholic church within the Encyclopedic Palace at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013 and his mammoth We The People project with the Public Art Fund unveiled earlier this year have catapulted Vō into the contemporary art stratosphere. Yet, even before reaching such critical mass, Vō’s smaller, more intimate works have issued profound considerations of class, cultural identity, and freedom in any and every respect.

Danh Vō, “Chung ga opla!,” 2013. Installation view at Villa Medici, Rome. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo by Roberto Apa.

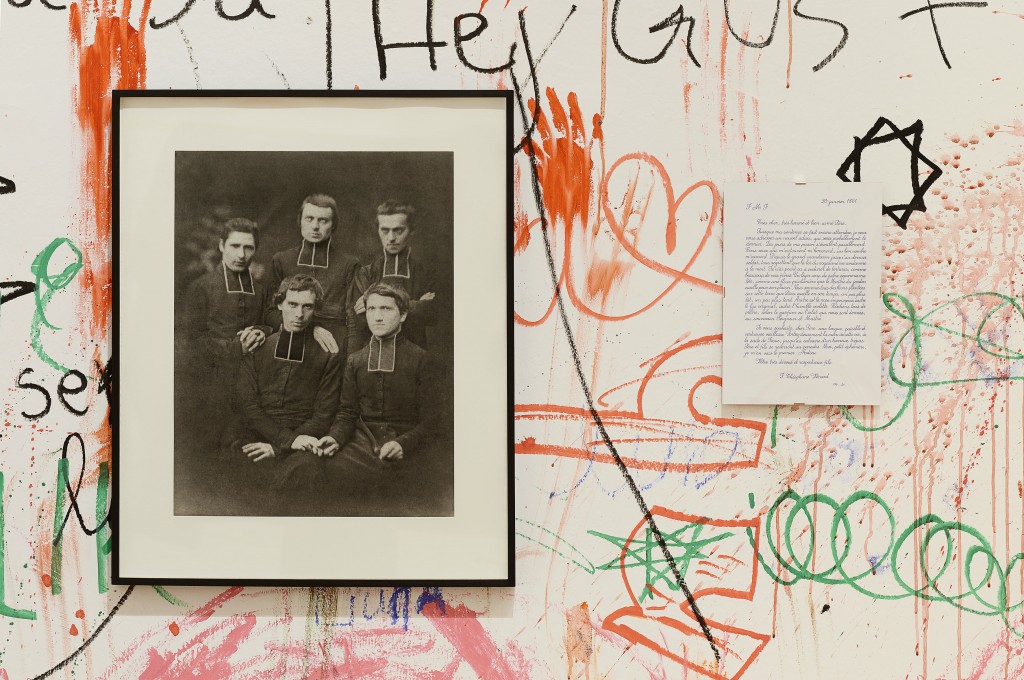

A particularly heartfelt example of the transmission of legacy and selflessness is found in a letter originally written in 1861 by Saint Théophane Vénard to his father before his execution. At 31 years old, the young Catholic missionary was beheaded by order of a mandarin, during a time when proselytizing was outlawed in northern Vietnam. Vō resurrected the defiant words of the saint (originally written in English, translated into French) by having his own father, Phung Vō (who speaks neither English nor French), transcribe the letter by hand into a near-perfect cursive copy. The project is officially called “02.02.1861, [last letter of Saint Théophane Vénard to his father before he was decapitated] (2009–).” This object, at first a historical artifact now sublimated into a creative gesture, is an appropriate exemplar of Vō’s significance in a densely populated, competitive industry. An artist reaches beyond their own chronology into a documented series of events informing, disrupting, and shifting a broader, less obvious perception of our current environment. Vō successfully inhabits the roles of archaeologist, cultural anthropologist, archivist, artist, and the casual flâneur: a vigorous cultural chameleon who can simultaneously adapt to and comment on any locale he chooses to visit.

Danh Vō, “Chung ga opla!,” 2013. Installation view at Villa Medici, Rome. Courtesy of Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie.

Vō has taken a countless set of conceptual and physical routes since infancy, and it is apparent that his passion is to engage in a perpetual state of travel. It was recently announced that he will again participate in the Venice Biennale in 2015, occupying the Danish Pavilion. What a Vietnamese-born, Danish-raised, Berlin resident artist will offer on the world’s largest stage for contemporary art is anyone’s guess, but it will surely be another illuminating journey both for him and his viewers.

“A good traveler has no fixed plans, and is not intent on arriving.”

-Lao Tzu