The Sea Becomes a Stage:

The Whitstable Biennale; a Festival of New Visual Art, Film, and Performance

By Lily Magenis

In its seventh edition, the Whitstable Biennale presented 45 artists over three consecutive weekends from May 31st–June 15th. Whitstable, a fishing and harbor town on the north coast of Kent, most famous for its Oysters, had once again been transformed into an art hunt. The majority of the art had been commissioned especially for the biennale and every other year continues to prove a radicalization of this small seaside town. The Whitstable Biennale brings new visual art, film, and performance to some of the most unexpected places.

Rosa Ainley’s piece was hidden away in the Whitstable Umbrella Community Centre Cafe. Greeted by a lady selling ice cream that also donned the role of gallery assistant, visitors were directed to the back end of the café. A rather inconspicuous audio plinth with a pile of pamphlets was all to be found, but when listening to the 10-minute audio while flicking through the pamphlet, everything seemed to come together. Ainley’s research into the Pfizer pharmaceutical complex near the town of Sandwich, Kent leads to her fictional work entitled “Building 519, and other Pfizer Tales.” It explored the notion of “if these walls could talk” by investigating the results of recording past thoughts and memories of a Pfizer pharmaceutical complex. The audio included interviews with Pfizer staff and aims to reconstruct a place.

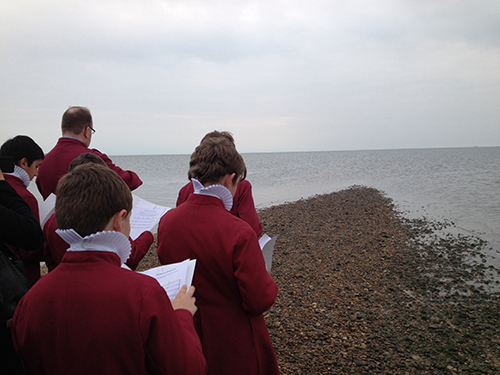

Louisa Fairclough, “Compositions for a Low Tide,” 2014. Performed by Rochester Cathedral choristers.

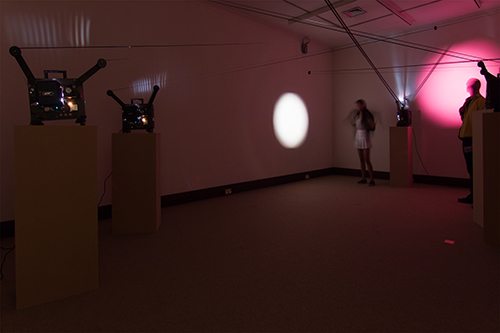

Though disappointed to have missed Louisa Fairclough’s “Compositions For a Low Tide,” her film sculpture, “Absolute Pitch,” held similarities. “Compositions For a Low Tide” was performed by the Rochester Cathedral choir on the opening evening of the Biennale. The choristers took a small group of visitors a mile out to sea at low tide and sang a piece of text taken from two drawings by the artist. The dual singing enabled a type of conversation between both groups—voices drawing in and out—that in a way mirrored the overlapping waves of the tide they were surrounded by. “Absolute Pitch” was a 16mm film instillation in the Whitstable Museum & Gallery that existed of five filmstrips weaved across each other to each corner of the room that looped back to their projectors. On each filmstrip was a single note sung by a member of the choir sustained for as long as possible. On the backside of each filmstrip was a single block of color that created the projection of white, red, and green balls that bounced from wall to wall, coinciding with the individual trails of voices.

Jeremy Millar, who lives in Whitstable and works in London, conceived an auditorium made of old grey sacks. Built inside the Royal Mail Delivery Office, his makeshift space was one of the first galleries en route from the train station to the coast. “XDO XOL” was a 45-minute film about time and place. A man dressed in a suit and coat has found himself foreign to the British harsh and wild terrain. We’re unsure why he is there, but as it cuts to him sharpening a bone against walls of his house, it seems he knows exactly what he is doing. Millar’s film was threatening but at the same time quite dreamlike. Cutting from clips of violent winds to a frog staring directly through us, Millar’s voyeuristic film flits between the cruel realities of survival and the beauty of nature.

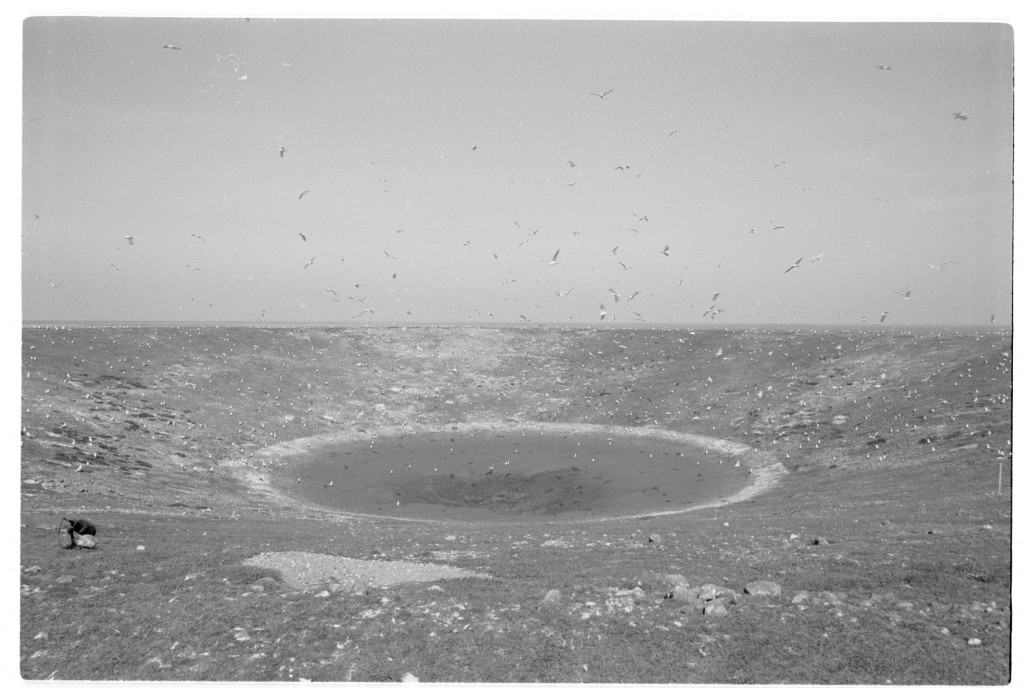

Neil Henderson’s “Tidal Island” was completely magnificent. Shown in the Sea Cadet’s Hall, he too used film to project a sense of place. His 15-minute time-lapse footage is of the artificial island Outer Trail Bank, which is off the Lincolnshire coastline. Outer Trail Bank is now only accessible at low tide, and “Tidal Island” captures the daily movement of this landscape. Such a beautiful scene only seen by birds, Henderson admitted us to our own private view.

John Walker redeveloped a beach hut to house his performance, “Turn My Oyster Up.” Situated on the very edge of the Biennale map and a charming 10-minute walk along the beach path, this was definitely a venture to make. Walter performed as host and offered a gin and tonic to each visitor, along with a gypsy tart—a locally made delicacy. It’s unclear what the purpose of Walker’s performance was other than to provide an alcoholic pit stop; nevertheless, his wacky costume, which matched the wallpapered hut interior, was good fun and offered a chance to interact with contemporary art and artists alike.

Laura Wilson took a more bleak approach for her piece “Black Top,” a site-specific film shown inside a harbor’s ominously named shipping container, Dead Man’s Corner. Wilson’s piece was a research project that recorded a month at the aggregates factory, which still runs on Whitstable harbor. The film consisted of a man driving a shovel and mounting asphalt into piles every day. She revealed the monotony of working life, yet her use of the seaside background brought her film to life. Wilson allowed us feel as though we’re part of a Whitstable necessity.

The Whistable Biennale was manageable in a single day. What was most appealing was not only the art itself, but the process of tracking it down in unsuspecting parts of town. My search for a specific meaning in a lot of the art failed, yet it was relieving to discover that not all seaside art has to consist of “found objects” and driftwood.

The Whitstable Biennale’s greatest ability is to provide first-hand encounters with art and artists, though during the second weekend, there was perhaps a shortage of performance, and a little too much film. However, considering all of the productions were free of charge and the Oysters were sold for as little as 60p apiece, along with an excuse to spend a day in this beautiful costal town, there was little to complain about at the Whitstable Biennale.

For more information, visit Whitstable Biennale.

Previous contributions by Lily Magenis include:

Review: Exhibition of works by Hannah Höch spanning the 1910s–1970s at Whitechapel Gallery, London