Rudolf Frieling

Interviewed by Ben Valentine

This interview has been pulled from SFAQ Print Issue 16.

Rudolf Frieling is the Curator of Media Arts at SFMOMA. Frieling came to SFMOMA in 2006 from the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany and most recently organized “Stage Presence: Theatricality in Art and Media” in 2012. Frieling’s deep investigation into media history and theory, makes him uniquely equipped to talk about how new media artists are responding to important issues today.

Given the revelations around massive surveillance in this country and abroad, surveillance has been at the top of our collective consciousness. Talking with Frieling uncovered how art might tackle this complex issue that we, as a society, are scrambling to try and understand. I was honored to talk with Frieling over the phone and learn more about the roles artists, curators, and collecting institutions can or should fill in this debate.

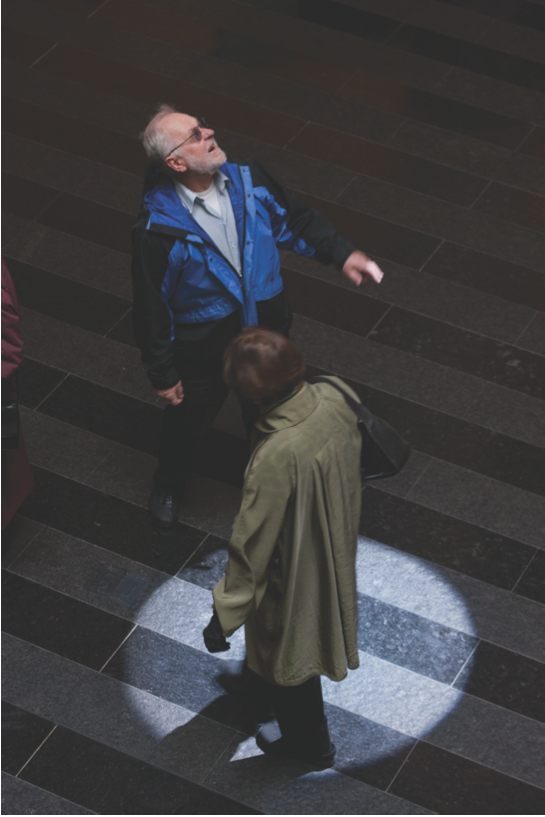

Marie Sester, “Access,” 2003 (2010 SFMOMA installation detail); Online project (www.accessproject.net). Custom software and electronics, robotic spotlight and acoustic beam, and cameras; dimensions variable; Project supported by Eyebeam, New York and by the Creative Capital Foundation, New York. Courtesy the artist; photo: Ian Reeves, courtesy SFMOMA; © Marie Sester.

You worked on “Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870,” I wasn’t living in the Bay Area to see it, but it looks like a phenomenal exhibition. Can you talk about how that show depicted and understood surveillance?

First of all, it is correct that I worked on it, but I didn’t curate the show. It was really the brainchild of our senior curator of photography, Sandra Phillips, who had been working on that for many, many years. When she proposed the subject of surveillance and voyeurism, I thought that would be an ideal opportunity to collaborate, and to try to take the show a little further than photography exclusively. So I added a few media works, mostly video, to that show, but the overall concept was really based on Sandy’s curation and her historic vision of the inherent voyeuristic and surveillance aspect of photography as a medium.

Our initial conversation involved the question of what is surveillance in the 21st century? We were wondering how could we bridge that gap between a historic narrative around photography and a more data driven, media driven look at surveillance as of 2009/2010, when we were organizing the show. Just to be clear, this was pre-NSA, but the topic was obvious even then, just not to that extent. However, it turned out to be a really, really difficult argument to coherently stage in an exhibition where you have almost more than a hundred years of photographic practice with a few data projects at the end. So we actually decided to focus on the camera, which is why it was eventually added to the title. I think that was a wise choice.

It was not easy to install, specifically when you think of the difference of formats. Most historic photographs are smaller in scale, while a lot of media-driven artwork is rather large-scale in format. With that in mind I would still make the argument today that we didn’t fundamentally miss out on new approaches, although tools really have changed. Tools like camera surveillance, as opposed to data surveillance today, are fundamentally different in scale and in impact, but the drive and the politics of exposing something or spying on someone haven’t changed substantially. I would still say the show was an excellent survey of the last hundred years.

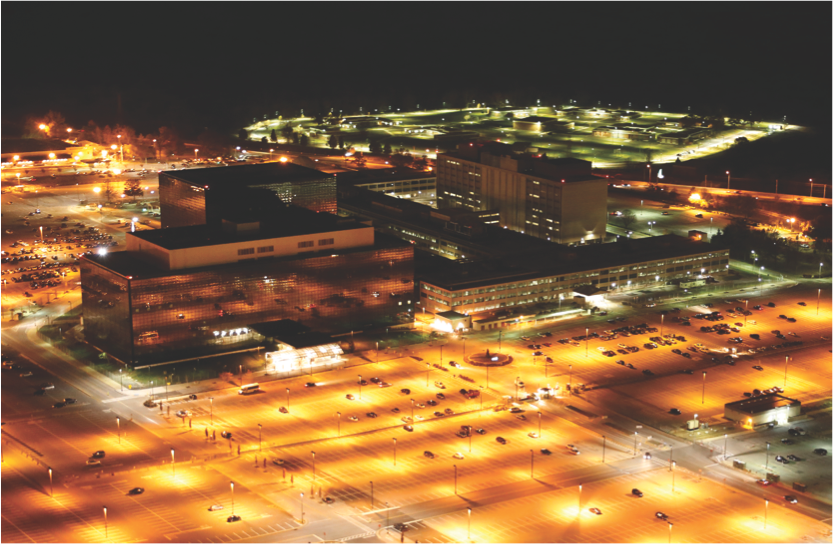

Trevor Paglen, “Aerial photograph of the National Security Agency,” Commissioned by Creative Time Reports, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

What role do you see art playing in examining, confronting, and maybe revealing surveillance tactics and methods? What role do these artists serve in the larger political or public discourse?

Art very often deals with pictures, not exclusively, but predominantly. Visualizing surveillance processes is quite difficult while visualizing data information is easy in comparison. So there’s the difference that artists are trying to tackle the impossibility of visualizing the politics of surveillance, rather than simply visualizing data.

For example, if we take Trevor Paglen, one of those important artists today who was actually part of the show, his work is as much about uncovering what we are not used to seeing, as it is about the implication and hinting at what that might mean, what that infers. So if you picture military satellites that cross over the sky, it still looks like a night sky. The important part is that you know that you are also looking at a military practice that is global. So that is much more of a mental picture, sort of a knowledge-base associated with a picture of something you can actually see.

Something quite different is Paglen’s series “Symbology,” where he discovered and collected patches from top-secret military units. I find that an extremely interesting component where he points the viewer or visitor towards a desire, almost an unconscious desire to still be seen and create a visual identity, a desire to get out of that box that these military units are in, which is one where you must not be seen, you must not speak about what you do. We are confronted with the return of the repressed through those patches and insignia, which then can be collected and exhibited. So one can find traces of what’s going on in disguise and yet out in the open, and in that sense it is at times an investigative journalistic side that artists take on or an active practice against censorship, for example.

Paglen has a very similar practice as an investigative journalist, almost identical, but then his reports, his investigations, end in the visual, whereas most investigative journalists produce texts and facts. Can you expand on that difference?

Let’s just say the hope of every artist is that the picture says more than a thousand words. It doesn’t always do that, but that’s the hope. The important aspect, the important difference is that the picture doesn’t have a clear message. The work includes ambiguities that are not necessarily part of the investigative message, where you uncover something and communicate it as clearly as possible. So maybe you would want to compare a visual arts practice as being in relationship to those, let’s say, activist kind of practices. So to move and to stay in the realm of the arts is a decision to link a whole history of visual discourses and art or media historical discourses to what you’re doing, in the hopes that there is a much broader resonance with every single picture or video produced.

It can get ethically murky at times when artists use photography or documentation as a way of surveilling themselves. Making instances where the audience becomes surveilled. Can you talk about that power dynamic?

This would certainly be within my understanding of what the arts could do or what an art institution should do. The gallery provides a space and a moment to actually address that relationship. Let me give you one example that is also about our history here at SFMOMA. We are currently working on the new building and the display of our collection. One way of doing that is to actually review works in the collection that have a specific relationship to who you are and to the spaces that we have. One of these prime examples is work by the American artist Julia Scher called “Predictive Engineering.” Julia is the most important artist of an older generation coming out of the 1980s working within the realm of surveillance. “Predictive Engineering” was a site-specific installation in SFMOMA’s first building on Van Ness Avenue in the Memorial building, and it had a specific relationship to two corridors in that site when it was premiered in 1993.

Let me say it’s a complex installation, but the basic is that there is an aesthetic of surveillance on monitors and that aesthetic is enhanced by not only real time feeds, but also by pre-recorded, fictitious footage. So you get a mix of fiction and reality and it’s quite unsettling, because you never know what the reality of a picture is. That was expanded in 1998 in the new building on 3rd Street and was called “Predictive Engineering II.” It incorporated parts of the first version but it also featured voices of people who could speak into a microphone, and then these voices of visitors would be cycling through the installation. Now that is a work from the 1990s, and initially I thought that this should be something that we should include in “Exposed” in 2010, and it turned out that the way it was programmed was obsolete and didn’t function any more. We included simply a related website as an extension of the 1998 installation.

Julia Scher, “Predictive Engineering 2,” 1998 (1998 SFMOMA installation view); multi-channel video installation with sound; dimensions variable. Collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund purchase; photo courtesy SFMOMA; © Julia Scher.

That experience put the work back onto our radar and ultimately back onto our agenda. Having time now to look more closely at the changes throughout those last twenty years, one thing immediately came up in my conversation with the artist: In the 1990s, the shadow of and the fears related to Big Brother were very much at the topical forefront of the project. Today, with our practice of constantly disseminating pictures that we take, pictures that are our own, it is her claim that something has fundamentally changed and that now it is as much about the way that we are seen and surveilled, as it is about the desire to be seen and to disseminate information. So what effect this will have on the reconfigured installation in the expanded building once we’re open in 2016, I don’t know. We just started that process, but I think the opportunity to rethink and reinstall histories of surveillance, at the same time reflecting on what surveillance might mean today through an artwork, is a wonderful opportunity.

That leads nicely into my last question, which is about our increasingly networked experience of culture right now, where we’re all surveilling each other and ourselves, a type of sousveillance. Many younger artists are joining in a kind of a networked culture production and many new works exist solely online and on social platforms. Please talk more about how issues of surveillance are complicated by that new paradigm?

I don’t think I have a good answer for that today since there is so much happening as we speak. If one thing has become clear, it’s the speed of changes within our networked existence, which is just mind-boggling. Specifically, as someone who is working in an institution that is preoccupied with the way this relates to histories and narratives in the arts, it is really hard to stay on top of things, and so it’s helpful to identify some artists with whom you can work, and with whom you can at least tackle such a problem without necessarily finding an answer.

I will just say in general, there are two approaches, which make it at times challenging to work as a curator of media arts in an institution. One is that either for political reasons or other reasons, some artists refrain and stay away from an active engagement with the media and take great pains to not be associated with the discourse around media, but rather only with the discourse around art. That’s been an ongoing problem for media artists ever since that field emerged. The second thing is that being in San Francisco we are much identified with our proximity to Silicon Valley, and to the innovation of future technologies, and it is expected from us that we find artists that showcase these new developments. That very often tends to be an affirmative position and to highlight the new software as a new creative tool without allowing for a more critical, nuanced and deeper engagement with histories and narratives. So if you think about, as just one example, Creators Project featuring interactive and fun installations that are software driven within an event context, it doesn’t really do more than what we already know about interaction and participation, which is that you can have fun with that.

This typically doesn’t address the specific limitations and conditions of participation, and I mention that because I curated a show in 2008 called “The Art of Participation,” and that was one of the criticisms that we received, that we weren’t participatory enough. My counter-argument was always that that was fine, that it was actually not our job to turn the museum into a fun house and to enhance creativity around participation, but rather to find and identify different ways of understanding the opportunities but also limits of participation. So from non-participation to excessive over-the-top participation, there’s a whole range of different approaches, and on that note I would also say that the topic of surveillance should produce art or artworks that actually have a longer shelf-life than the current technology of the day.

If you fast-forward ten years from now and look back at something that might seem very pertinent and urgent today, just imagine how that is still something that goes beyond the use of a particular technology. It addresses more fundamental concerns. So that’s something we’re trying to do, and I very often find myself in that position that I need to make a decision on how to stay contemporary in what we collect, how to identify works that really keep us engaged in a much longer conversation than just addressing the NSA and the Snowden dynamics today.

Oliver Lutz, “The Lynching of Leo Frank,” 2009 (2010 SFMOMA installation view); Acrylic on canvas, CCTV system; painting: 60 x 87 in. (152.4 x 221 cm) overall dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist; photo: Ian Reeves, courtesy SFMOMA; © Oliver Lutz.

Do you have anything else that you would like to add or talk about?

You brought up an interesting project in your email which is a much more recent example of censorship and institutional policy around legal practice, which was the project “PRISM: The Beacon Frame” by Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev. I was not there in Berlin at the festival, so I didn’t experience it, I’ve just been reading about it. First of all, it’s a fascinating project, I’m not sure that it will remain an interesting project in the long run, but it certainly seems very contemporary and very urgent right now. The way that it unfolded at Transmediale, which as a full disclaimer I helped found in the late 1980s, was that someone felt responsible and acted out a kind of policing of that work in response to some criticism that was voiced on the opening night. The festival took the very legal position saying here’s something going on that might be considered a breach of privacy laws. Now Transmediale is funded by government agencies, so they felt they can’t be complicit with that. I respect that, I understand the position, but I also think at the same time it’s the wrong attitude and the wrong approach.

Let me backtrack a little bit and point to an older practice in which artists, through video recording technology, have recorded and appropriated films. Christian Marclay being the most widely recognized example, but the practice is much older. It’s been an issue for some museums to then say to the artist, “Can you guarantee that you cleared all copyrights for that?” Obviously, an appropriated collage of Hollywood movies can never, ever be in clearance of copyright laws, because artists wouldn’t have the financial means to do that. Yet at the same time this appropriation is an important cultural reflection of our times, and I think that’s a key to our mission, that we reflect what artists do and how they specifically react to our culture. Today, museums don’t necessarily request any more that all the copyrights have been cleared, but they act on the trust that—if it ever becomes an issue—this will be discussed as a part of what museums do and what artists do and that this will be discussed as part of a fair use policy. One way of embracing that is to say, “well, we’ll see if this becomes a problem.” If it becomes a problem we’ll then address it. So what the festival in Berlin did was a kind of self-censorship and to shut down the project—as opposed to an approach where one keeps it running to have these conversations, legally, politically, artistically, that it might trigger.

What’s more, it felt like that was the desire of the work, and presumably of exhibiting it, to have that conversation.

Yes. You cannot embrace conflict and foster debate around an ongoing practice only from a legal point of view. Alternatively, where would you have that sort of experience and discussion if not within the arts? So I think we have a special obligation to address these issues.

Previous articles from SFAQ print issue 16 include:

In Conversation: David Bayus with Luca Nino Antonucci