By Shana Beth Mason

Judy Chicago, “Purple Atmosphere #4,” 1969. Photo documentation

courtesy the artist and Through The Flower Archives, New Mexico.

Judy Chicago has never been one for subtlety. Her straightforward challenges to patriarchal aesthetics and critical structures in and since the late 1960s have been realized in the form of iconic works such as “The Dinner Party,” “Red Flag,” and “Rainbow Pickett.” But the lesser-known pieces of a prominent artist’s oeuvre are, oftentimes, the most satisfying elements of their practice. A glimpse into “Chicago in L.A.: Judy Chicago’s Early Work, 1963-74” at The Brooklyn Museum is one such example. Held in close proximity to her epic “Dinner Party” installation at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Chicago’s polished domes, photographic and video documentation of her early performances (called the “Atmosphere” series), and a healthy offering of works on paper are just peepholes into her immense career.

The transition from Judy Gerowitz (her married name to husband Jerry, who died in a car accident in 1963) to Judy Chicago is directly related to the woman, herself: more than just a pen name, it was a near-complete identity shift from that of a married, “domestic” female figure into one broken free from such ideological labeling. At the half-joking suggestion of gallerist Rolf Nelson, the 31 year-old artist adopted the surname “Chicago” in 1970 not just to mirror her prominent, Midwestern accent, but also to provide a defiant persona for an artist versus a male or female artist. The October 1970 issue of “Artforum” held, within its pages, an image of Chicago sitting at the ready in a boxing ring, wearing a grey sweatshirt emblazoned with her new surname. Chicago would, and continues to, explore how the concept of the feminine and all of its imagined anthropological associations inhabits the most hardened environments and scenarios.

Dry Ice Environment, 1967, collaboration between Judy Chicago, Lloyd Hamrol and Eric Orr, performance at Century City Mall, Los Angeles, CA, dry ice and flares, photo courtesy of Through the Flower archives.

Chicago’s “Atmospheres” series effectively commenced in 1967, with her “Dry Ice Environment” installation created alongside Lloyd Hamrol and Eric Orr at the Century City Mall in Los Angeles. It was her proverbial route towards a “softened” or “feminized” landscape: she would place blocks of dry ice or colored flares in remote natural areas or wide public spaces and photograph the ghostly trails of sublimated gas. Chicago’s personal notations and reflections, mounted and framed in chronological order, accompany photographs of these early investigations. Later versions would include nude female figures (sometimes painted head-to-toe in shiny, strong colors) meandering through or meditating within the fluctuating air. These early films follow in the important pathways carved out by pioneering female artists of the time including Yoko Ono (“Cut Piece,” 1965), Carolee Schneemann (“Meat Joy,” 1964 and “Fuses,” 1964–67), and Valie Export (“Action Pants: Genital Panic,” 1968). It must be noted that Chicago, in her own words, “had no interaction with these women. I was on my own in Los Angeles in a male-dominated field. I was familiar with them, but had never met them.”

Judy Chicago, “Rainbow Pickett,” 1965-2004. Latex paint on canvas-covered plywood. Collection of David and Diane Waldman, Waldman Family Trust, Rancho Mirage, CA. Courtesy the artist and the Brooklyn Museum, New York. Photo credit: Donald Woodman.

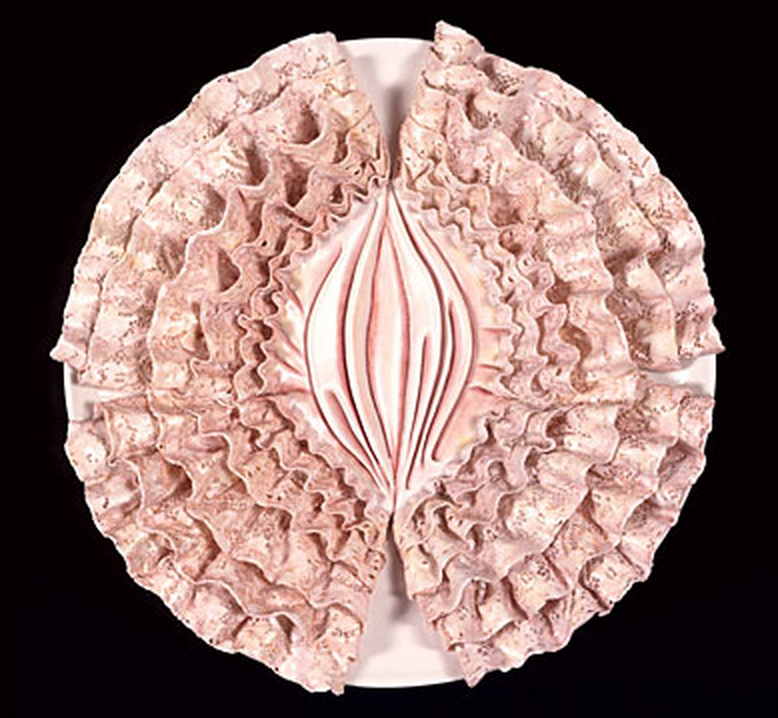

Shortly after the creation of the first “Atmospheres” elements, Chicago’s move towards geometric abstraction became more forceful. She also delivered distinctly female commentary on L.A.’s signature “finish fetish” movement. “Rainbow Pickett” came to fruition (once in 1964 and again in 2004) with its gentle, bright coloring. Sets of bulbous domes (in polished steel, acrylic, or glass) could fluctuate between topographic peaks or pristinely crafted sex toys. Chicago’s full-spectrum drawings (such as the “Donut Drawings,” “Pasadena Life Savers,” “Fresno Fans,” and the “Flesh Gardens” series) were, at the time, daring Minimalist studies in regard to their softened gradients and vivid, rainbow tones. Finally, Chicago’s magnum opus, “The Dinner Party,” seals the level of mastery in with her audience as an exhaustive tribute to females both legendary and indispensable to the history of the world. Housed in a darkened space made to mimic the exact shape of the giant triangular table, the work consists of 39 place settings (13 per side) each with a unique tablecloth and plate design, resting on a similarly shaped platform composed of 2,304 hand-cast gilded and lustered white tiles with the names of 999 important women written in gold.

Judy Chicago, “The Dinner Party,” 1974-79. Ceramic, porcelain, textile, 576 in. x 576 in. Courtesy the artist and The Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation at The Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Judy Chicago, “Emily Dickinson Plate,” 1979. China paint on porcelain, 13.75 in. diameter. Photo by Donald Woodman.

Early on, Chicago had taken instruction in auto-body work, ceramics, and how to handle fireworks. These would all prove to be invaluable weapons (no pun intended) for the artist’s arsenal, but through all of her diverse processes, she remained ever loyal only to her own intellectual and spiritual curiosities. Throughout the years (at the request of no dealer, no collector, and no auction house), Chicago has boldly delved into difficult issues surrounding menstruation (“Red Flag,” 1971), masochism and violence towards women (“Love Story,” 1971), the Holocaust (“Rainbow Shabbat,” 1992), and a general desire to hang on to beautiful moments bound to end (“A Butterfly for Pomona,” 2012). On the occasion of her 75th birthday this year, her latest performance was staged in Prospect Park—her first ever in New York—entitled “A Butterfly for Brooklyn.” This coalesced with previously staged events including “A Butterfly for Oakland,” 1974, and “A Butterfly for Pomona” (part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time program in 2012). These celebratory happenings only reinforce one of the most common universal idioms: it is never too late to begin anew.

Judy Chicago, “Acrylic Shapes,” 1967. Formed acrylic, 10 in. x 24 in. x 24 in. Collection of Penny Plotkin. Courtesy the artist and The Brooklyn Museum, New York. Photo credit: Donald Woodman.

To date, her journey towards international recognition has not been realized. For all of her accomplishments and leadership in contemporary art through conceptual, performance, installation, and even the attribution of the term “feminist art” going to her, she has yet to have her work acquired for the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Guggenheim, the Whitney, Tate Modern, the Pompidou, or, shockingly, the Art Institute of Chicago. This exhibition is no vindication for that tragic oversight, but it is certainly a triumph on its own as a thoroughly charted course through Chicago’s singular commitment to upending the dominant male status quo in the visual arts.

“The Dinner Party” is on permanent display at the Brooklyn Museum.

Also on view at the Brooklyn Museum:

April 4–September 28, 2014

“Chicago in L.A.: Judy Chicago’s Early Work, 1963–74”

Previous contributions by Shana Beth Mason include:

Review: Matthew Schreiber: “Sideshow” at Johannes Vogt Gallery, New York City

Review: “Brian Fridge: Sequences” Solo Exhibition at Horton Gallery, New York

Review: Pick of the Litter: Armory/Whitney Biennial Week New York 2014