Excerpts from a conversation with Jesi Khadivi (Assistant Curator at the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art) about “/* Reject Algorithms*/” solo exhibition by Miguel Arzabe at CULT Exhibitions, San Francisco.

Jesi Khadivi: I’ve been thinking about the role that the body plays in your video, “/*Reject Algorithms: key */.” This work documents and reconfigures the process of creating the paintings that one sees in the gallery. With regards to the physical weight of performing painting, this body of work can be seen as referencing precedents like Namuth’s photographs of Jackson Pollock, or Murakami busting through canvases in a Gutai performance—or any number of artists who have used the body as a way to make indexical marks, making use of “surface friction,” so to speak.

But the way your body appears in your video has a different kind of weight. It’s a bifurcated body, a fractured body. For example, you see your hands as they are making marks, sanding things away, applying masking tape. But then there is also this performance of jumping, movement, and gesture that seems like a kind of dematerialized digital body.

Miguel Arzabe. Excerpts from /*Reject Algorithms: Key*/, 2014, video, color, sound, 13 min.

Courtesy the Artist and CULT Exhibitions

Miguel Arzabe: The goal with this work was to not have a goal, to break patterns when I became conscious of those patterns. By chance I found a book at a thrift store of clip-art — isolated silhouettes of people playing various sports. I’ve played sports my whole life. For me it’s more like Zen: not thinking, but doing. I set up the studio, (a dancer’s studio) so that movement could be a part of the painting process. One side of my studio turned into a performance stage, and the other side of the studio was a production space for the paintings.

The movement, the jumping, seemed like a way of physically escaping rational patterns of thought. The camera was set up with a continuous automatic timer, forcing me to come up with something new every moment. As I kept doing it, I thought about how we construct the way we want others to see ourselves online.

Exhibition view, /*Reject Algorithms*/. Photo by Tomo Saito courtesy CULT Exhibitions

JK: I’m interested in two ways that painting relates to performance. On the one hand there are hyper-authored performances of painting, like Pollock, while on the other hand there an emphasis on how materials behave —another kind of performance. I see what you are doing as hovering somewhere between the two. What’s your take on authorship? There is a disembodied hand that moves across the field of the video that, to me, seems to represent a sort of “authorial hand.” I’m curious as to how this depiction of the fractured body might relate to how technology—I don’t want to say fragments— but distributes our perceptions and our selves?

MA: There has been a lot of discussion in San Francisco about the way technologists approach art and the way artists approach technology. As far as the relationship between the body and the hand in the video, while I was making it I was mindful to withhold conclusions. I’m very invested in technology. Because of the way it distributes images, it can have an interesting conversation with painting, which is tied up so much in the concept of the aura of the physical object. With the hand I wanted to demystify the processes that not only construct the painting, but also the aura of the painter. A lot of what technology is trying to do is create “frictionless” experiences. I think there is value in friction—that’s what tells us we are human beings in a physical world. Our biological history is filled with friction. I don’t want to give that up so easily.

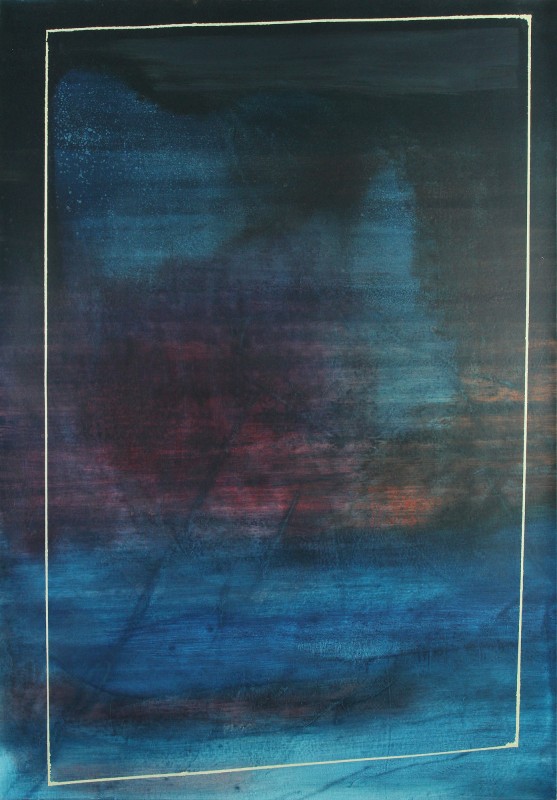

Aimee Friberg (Gallerist/Curator at Cult Exhibitions): I can’t help but see the reference to the digital world, especially in these paintings that have the rectangular outline. We spend so much time looking at a computer, so there’s this reference to the screen, but at the same time there is also this cosmic reference to endless trajectories in analog space. Is that something that interests you?

Miguel Arzabe, /* Reject Algorithms: indigo*/, 2013, oil on canvas, 54 x 38 in. Courtesy the Artist

and CULT Exhibitions

MA: The all-over field of abstract expressionism shifted the focus away from any one part of the composition so that you could actually see the paint. The screen, rather the rectangle that references the screen, interrupts that field. Paradoxically, it also allows us to see the painting anew, again because we are so used to seeing through rectangles now. It helps people, if it weren’t there, you probably wouldn’t look at the painting for so long.

AF: How does this relate to the green screen? The green paper on the doors of the gallery, the green in the paintings and the video?

MA: Other artists gave me their oil paint, including three big tubes of sap green. I had a leftover strip of green paper. It looked like a green screen when put on the wall. The chroma key function allows one to “key” out a specified color in a video – usually green making that part transparent. It became a way to use video like paint, by concealing and revealing layers. The green suit I wore let the paint show through my body in the video.

JK: Cycles of production and destruction are so prevalent in action painting postwar. Looking at your work, how do you see the process of creation in the context of current technologies of reconfiguration, distribution, and recycling?

MA: If we look at the way that we create online, we see that the labor of the people that create content isn’t necessarily valued more than those that aggregate and reconfigure it. How could a personal art practice work in light of this? I put emphasis less on making a “masterpiece” than a network of objects and dematerialized objects, like video, within an installation where each piece can be both part of the network and also hold something of its own as a physical thing in the world.

Exhibition view from the outside of the gallery through smartphone-shaped peephole. Courtesy the

Artist and CULT Exhibitions

JK: Exactly, it’s like the painting become multiple things at once. In the video the paintings almost become like data, or information. It got me thinking about the invoicing and documentation of labor, which made me think about the work in the corner, one of my favorites in the exhibition, “Four Years of Paint Scraps.”

MA: After every painting session I’d scrape the leftover paint off my palette and stick it in the tube. It’s like a geologic record of my color choices. I don’t like wasting anything every bit of material can be used again, reframed or repurposed, or can migrate through different forms.

/*Reject Algorithms: Four Years of Paint Scraps*/. Photo by Tomo Saito courtesy CULT Exhibitions

“/*Reject Algorithms*/” was on view through April 19, 2014.

For more information visit CULT Exhibitions, San Francisco.