“The Whitney Biennial”

Curated by Michelle Grabner, Anthony Elms, and Stuart Comer

The Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Ave, Manhattan, NY 10021

March 7–May 25, 2014

By Courtney Malick

It is often considered the most easily unlikable show to come along every other year. In part this is due to its wildly over-extended aim: What is American art at this very moment? As if a singular moment in which a word as ambiguous as “American” could even theoretically exist. Nonetheless, the Whitney Biennial has again come and has at least attempted to put forth a prismatic view of the most popular, if not compelling, directions in visual culture. Before delving into the artists and the work on view, it is important to note the three curators who, together though separately (perhaps such an arrangement itself a reflection of today’s modus operandi worth considering more closely), built the frameworks within which one museum became three parallel takes on contemporary art, physically situated one atop the other.

Jennifer Bornstein, Untitled, 2014. Video, color, silent, 4-30 min. Collection of the artist; courtesy Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York and greengrassi, London..

Beginning at the top of the museum, as it seems most viewers do then working their way down, is Michelle Grabner’s presentation. Grabner, who has been working predominantly in Chicago as an artist, curator, critic, and professor at the Art Institute of Chicago since the 1990s, certainly fits the multi-tasking mold of what anyone working in contemporary art most often—or dare I say—ought to look like. She wears many hats at the same time, which, unlike previous times, has become the norm. Grabner’s investment in criticality and pedagogy is prevalent in her curatorial statement. (It is also important to note that there is no over-arching concept or text of any kind for this, the 77th Whitney Biennial, but instead three separate, brief curatorial statements). Yet on the fourth floor, where the artists selected by Grabner, whose names are for the most part recognizable and thereby not unexpectedly included in such a definitively canonizing exhibition, criticality seems sorely missing. To most, criticality might connote a sense of editing—a slimming down not necessarily to the mere essentials, but to points along a line that relate to one another and take a viewer from one place to another without a myriad of detours along the way. There are certainly a number of strong works in Grabner’s compilation, most notably Jennifer Bornstein’s “Untitled” (2014) video from 2014 of two naked women on a beach taking various stances and poses based on anthropological findings of dances related to schizophrenia, postmodern dance techniques, and soft-core porn imagery of the 1970s.

Ken Lum’s “Midway Shopping Plaza” (2014), is an oversized 3D collage of replicas of typical signage from a Vietnamese strip mall that emphasizes consumerism, bright colors and multiculturalism in ways that are so easily felt they need not be described. Amidst a slew of too familiarly clunky, draping, textured sculptures and installations such as works from Sterling Ruby’s ceramic series “Basin Theology” (2013), Sheila Hicks’s “Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column” (2013-14), and an installation by Joel Otterson that included a tepee-esque tent in front of a wide sheet of hanging strands of beads, is the refreshingly dry and minimalist installation by David Robbins, Bookcase of Concrete “Comedy: An Alternative History of Twentieth-Century Comedy” (2013) in which eight books of the same title are wedged together into a square hole cut out of a large, wooden bookcase.

Sheila Hicks, Pillar of Inquiry: Supple Column, 2013-14 (installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). Collection of the artist; courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. Photograph by Bill Orcutt.

Altogether, Grabner’s exhibition renders contemporary art and, more significantly, contemporary culture as one that continues to be submerged in abstract, oversized forms that rely more heavily on their physicality than the depths of their intellectual value. Speaking in a curatorial sense, not a single one of these works, with perhaps the exception of Zoe Leonard’s gigantic camera obscura, “945 Madison Avenue” (2014), which fills up its own large room. Not one of the artist’s pieces has a single inch of room within which to breath, much less afford the viewer the same luxury. However, it ought to be noted that Leonard’s work was actually curated into the fourth floor by second-floor curator Anthony Elms. As a result, videos, sculptures, paintings, and installations alike get jammed up against one another, doing nothing to help Grabner clarify what it is she is trying to say about art in 2014, other than perhaps that it is messy and often full of misnomers, crossed lines, grandiosities, and plain, flat paint. Surely this assessment is not entirely false, but unfortunately it is perhaps one of the least exciting aspects of what it means to make or care about art today, not to mention that it makes for a jumbled and cramped viewing experience.

Though it’s unclear that in fact the stairway installation that runs all the way from Grabner’s fourth floor down to Anthony Elms’s second was selected by Elms, it is a very pleasant surprise after the amalgamated affront that must be tackled on the fourth floor. Charlemagne Palestine’s sound installation, whose poetic title harks back to the visuality of E. E. Cumming’s use of the page, not only echoes haunting, ambient sound, but also includes stuffed animals that, though they possess an air of creepiness akin to Mike Kelley, appear to be from the 1930s or ‘40s (even creepier actually!).

The third, much talked about “queer” floor, curated by Stuart Comer, Chief Curator of Media and Performance at MoMA, does in fact deliver on many fronts. First and foremost is the now infamously raunchy installation room by Norwegian artist Bjarne Melgaard, confined to its own area with colorful curtains at its entrance that act as a censor that warns: illicit content ahead. Illicit indeed, but more importantly, Melgaard’s microcosm of rubber sex dolls perched seductively (often spread eagle) on colorful, Jim Drain-esque sculptural furniture and rugs with videos and sound interspersed throughout, is perhaps the first time thus far in the biennial that the work on view and its curatorial agenda feel true to the “moment” as it were, in an attempt to be captured. It does this at least in part because of its fleeting and patchwork quality. No sooner are overtly sexual, gay, and animalistic acts engaged on screen than they disappear and are replaced by another flash of Dionysian excess.

Travis Jeppesen, 16 Sculptures, 2014 (detail). Mixed media, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist. Photograph by Mario Dzurila.

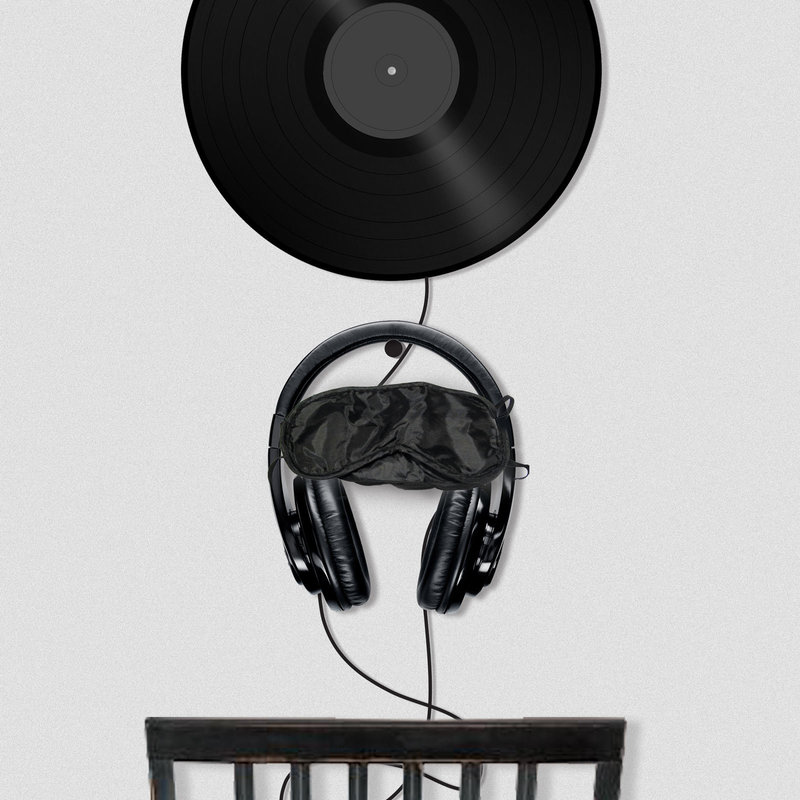

All the while, viewers must navigate their inherently precarious place within this crowded scene, some too uncomfortable to stay for more than a minute. Perhaps unknowingly, viewers also take part in Travis Jeppesen’s sound-based installation within Melgaard’s, sitting in chairs placed against one of the room’s walls. Blackout glasses and headphones are made available on hooks next to vinyl records of various artists.

Jacolby Satterwhite’s single-channel, 3D, HD video, “Reifying Desire 6–Island of Treasure” (2014), that similarly works on Melgaard’s homosexual and pornographic edge, but catapults such subjects into outer space where they exist in the even more esoteric, metaphoric depths of the Internet (aka the “inner web” where Melgaard claims to have found much of his visual material). A large, personal, and alluring collage-like installation of forty-six photos by Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst titled “Relationship” (2008-13) that, self-explanatorily, follows the couple through each artist’s gender transition: Drucker’s from male to female and Ernst’s from female to male.

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship (Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, 2011), from the Relationship series, 2008–13. Chromogenic print. Courtesy the artists and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Jacolby Satterwhite, “Transit,” Video Still from Reifying Desire 6, 2014. HD digital video, color, 3-D animation, Courtesy OHWOW Gallery, Los Angeles and Mallorca Landings Gallery, Spain.

With the additions of these both visually and conceptually strong works, as well as many other striking installations by Julie Ault, A.L. Steiner, Ei Arakawa and Carissa Rodriguez, and Fred Lonidier, Comer’s exhibition does touch on many important points on the current spectrum of American culture. Unfortunately, due to its relegation to the third floor, Comer’s exhibition reflects the only instance within the biennial where issues of gender, sexuality, identity, or even the contemporary effects of technology, the Internet, and social media seem to be addressed.

A.L. Steiner, still from More Real Than Reality Itself, 2014. Multichannel video installation, color, sound. Collection of the artist; Courtesy Koenig & Clinton, New York and Deborah Schamoni Galerie, Munich.

The second floor, which figures as either the first or last exhibition of the Biennial that one visits, depending on one’s route, is curated by Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art’s Associate Curator, Anthony Elms. Here we find, not unlike Grabner’s exhibition, a rather traditional approach to the question of art in America and, as outlined in Elms’s curatorial statement, the role of the Whitney entirely. It is strange to think that an institution so innovative as to have exhibited some of the most challenging work with regards to the role of the museum within the past five years should cater to overtly straightforward negotiations. (Christian Marclay’s “Festival” (2010) and Xavier Cha’s in-your-face, ongoing performance in the lobby gallery “Body Drama” (2011), immediately come to mind as examples of challenging works that have been exhibited at the Whitney.). Elms includes much strictly formal work such as figurative drawings and symbol-based paintings by Elijah Burgher, overly nostalgic ink drawings by Paul P., and a seemingly popular, somewhat garish installation of aluminum and silver wall sculptures by Terry Adkins.

Terry Adkins, Aviarium, 2014. Steel, brass, aluminum, and silver, dimensions variable (installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). Estate of Terry Adkins; courtesy Salon 94, New York. Photograph by Bill Orcutt.

There are, however, also moments of intrigue in Elms’s show that, though not all that shockingly, speak to the connective and referential methodologies of contemporary art, theory, and thought in general, that continue to work as powerful, even pedagogical tools. The inclusion of the Chicago-based collective Public Collectors mixed-media installation on the life of audio recording enthusiast and activist Malachi Ritscher seems an unusual choice that brings up questions of activism and suicide, as Ritscher notoriously killed himself by setting himself on fire in public in 2002. It also poignantly connotes the continued prominence and relevance of anonymity.

Joeff Davis, Malachi Ritscher, Iraq War Protest, Chicago, 2003. Courtesy the artist. Included in the project Malachi Ritscher by Public Collectors.

Another work in Elms’s purview that sadly fell flat was installed in the antecedent space of the lobby gallery where My Barbarian will perform “The Mother and Other Plays” (2014) throughout the month of March, and where papier mâché masks and similarly drab-colored, poster-like drawings appear as a static installation. As the first work that welcomes visitors to the biennial, this installation says a good deal about what is in store throughout one’s journey of the museum.

My Barbarian, still from Universal Declaration of Infantile Anxiety Situations Reflected in the Creative Impulse, 2013. Video, color, sound, 30 minutes. Collection of the artist; courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

While there are moments of insight when encountering specific works within the biennial overall, these three curators, with perhaps the exception of Comer, do little to change or even exaggerate the conversations that are occurring and laying one atop the other through various discourse-driven platforms that fuel the believed validity of contemporary art altogether. At its best, contemporary art today at once crystallizes and confuses what it means to be living, working, and perhaps resisting humanity throughout many interfaces of the world, which includes an endless number of oscillating screens and devices. To neglect this reality within a curatorial presentation of American art today feels not only irresponsible, but more importantly a hugely missed opportunity to reimagine and expand upon the idea of the museum as a place to both forge and tread alternative paths to consciousness and thought.

For more information, visit the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Visit The 2014 Whitney Biennial for programming.

Further contributions by Courtney Malick include:

–Courtney Malick in Conversation with Curator Santi Vernetti.

–SFAQ Review: Los Angeles Art Fairs 2014 – Art Los Angeles Contemporary and Paramount Ranch.

–SFAQ Review: Liz Larner solo exhibition at Regen Projects, Los Angeles.