“Brian Fridge: Sequences”

Curated by James Cope

March 5th—April 6th 2014

Horton Gallery | 55-59 Chrystie Street, Suite #R106

New York, New York, 10009

Secrets stay secret for Brian Fridge. The Dallas-based artist ensures that his working methods are sealed airtight from curious minds and eyes. Puzzling moving images, collectively titled “Sequences,” are overt challenges to how the viewer interacts with and reacts to the natural environment; cosmic turbulence, frozen air currents, and microscopic ballets are visually manifested in the action that unfolds. At the Horton Gallery, tucked away in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, two projections housed in two separate, spacious rooms harbor a selection of Fridge’s films.

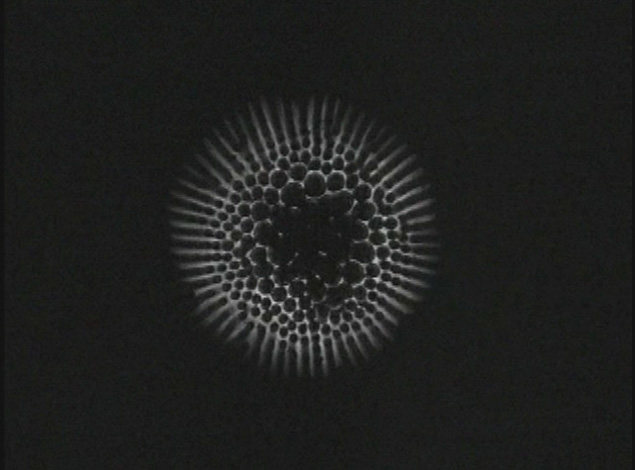

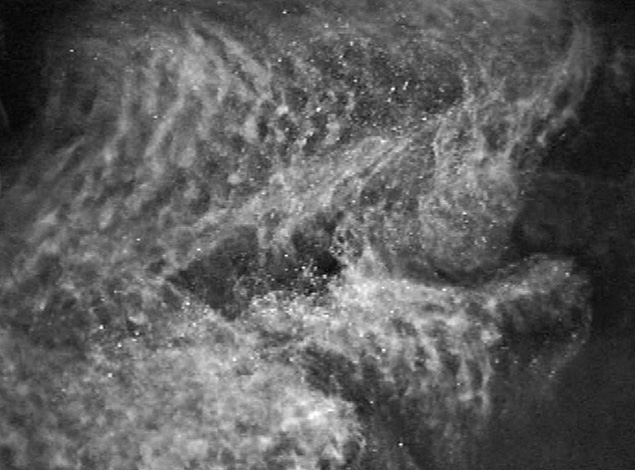

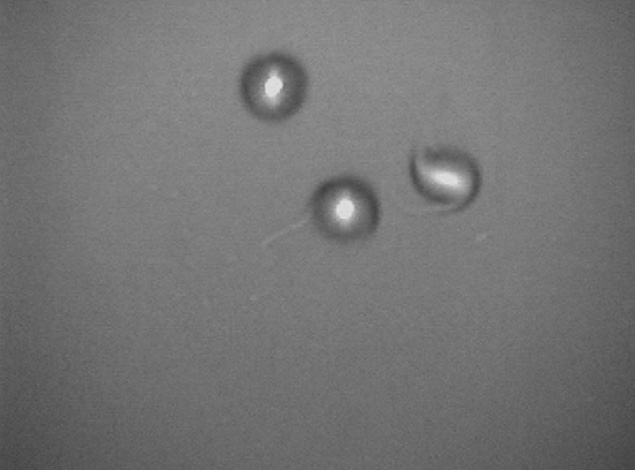

Fridge began his work in the late ‘90s primarily as a sculptor and painter. As time progressed, he directed his efforts into video with some of his earliest works comprised of simply constructed, but outwardly mysterious, feeds of television static and waves of condensation above an open freezer. One of these early “freezer” films, part of the “Vault Sequence” series (1995-97), runs in a loop for approximately five to six minutes without interruption (a variant of this was shown in the 2000 Whitney Biennial). The crawl of the icy air received by the lens resembles the slow swirls of deep-space nebulae and dying stars: one form of kinesis readily available to an earthbound audience, the other only accessible through cameras recording the past. “Sequence 11.14-11.5” (2009) is a dance between two spinning, galaxy-shaped objects that eventually consume one another against a buzzing gray field. For each of these films, a household camera behaves similarly to the Hubble Telescope as it seems to transmit data from a distant source, its actual components remaining firmly beyond identification.

“Sequence 1.6,” 1997, black & white, silent video, 1:50. Courtesy the artist and Horton Gallery, New York.

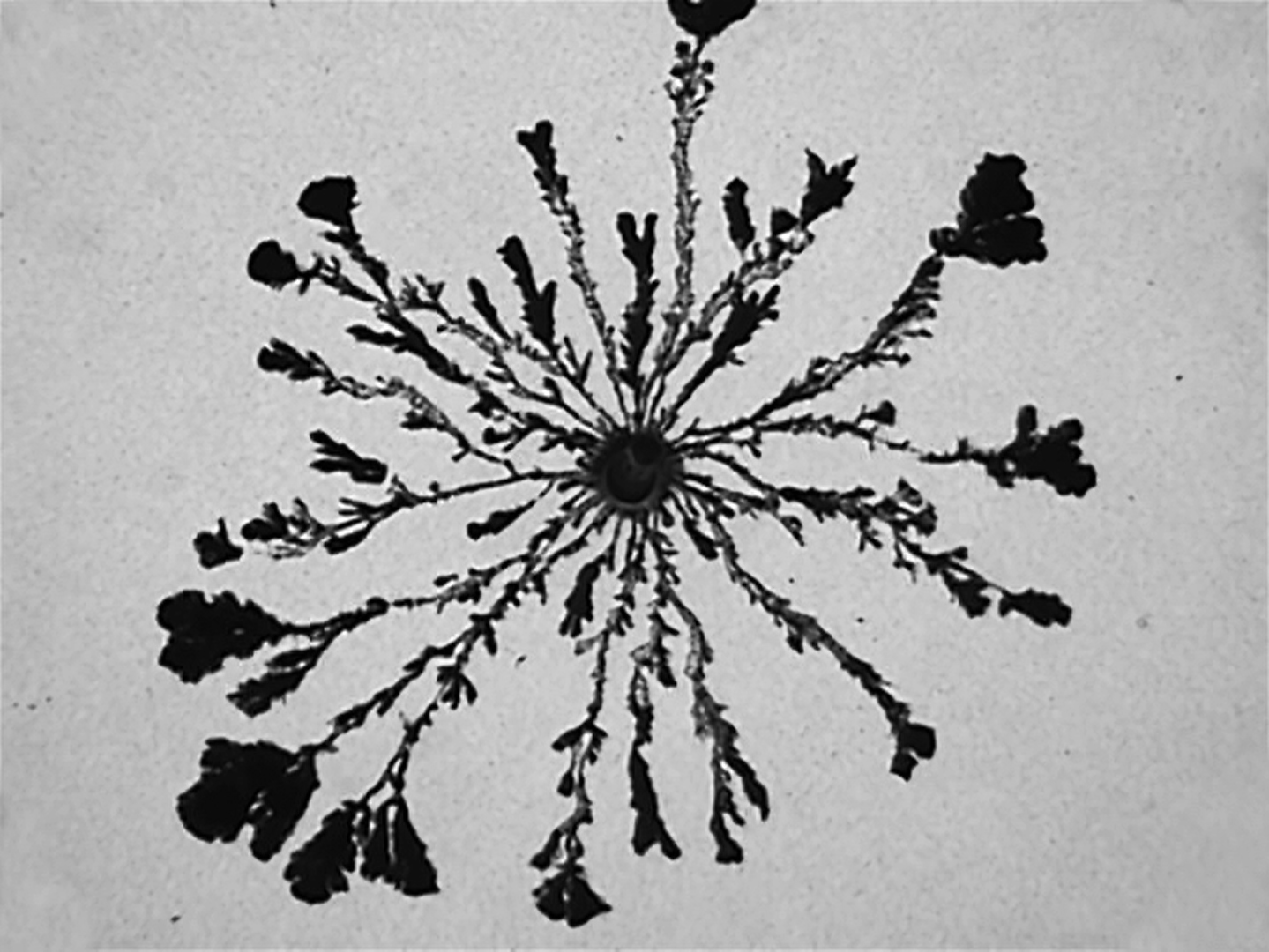

A more recent film in Fridge’s catalogue, “Sequence 36.1-36.5” (2010), occupies the second, larger projector in the gallery space. What appear to be delicate leaves, or living deep-sea coral, or maybe just the movement of dark pigment over a white background opens up before our eyes. This work feels Victorian with its deliberate, restrained motion reaching outwards in black and white; like ink traveling over parchment or a time-lapsed capture of a thistle blooming, it is organic and otherworldly. A weird melancholy settles in while viewing this. A brief moment of Emily Dickinson-esque pining occurs as black veins branch out from a darkened center point. Moreover, this family of sequences blurs the boundaries between something made by hand and something nature bore. The self-animating pathways are spontaneously generated signs of life that eventually reach a terminus. Is this a manmade scene or is a natural event occurring in real-time?

“Sequence 11.14-11.5,” 2009, black & white, silent video, 1:38. Courtesy the artist and Horton Gallery, New York.

Fridge is an experienced practitioner whose works have been under-appreciated by a broad audience. His work has been shown at nearly every major fine arts institution in the state of Texas (and select international venues such as the Turin Triennal and the aforementioned Whitney Biennial), but hasn’t been inducted into the collection of instrumental video artists working in the early ‘80s and ‘90s such as Nam June Paik, Bruce Nauman, William Wegman, and Carolee Schneemann. Despite being overlooked by major museums and private collections, it is particularly satisfying to regard Fridge as a hidden treasure amongst recognizable names. Unlike early video artists who enacted mundane gestures, Fridge rejects the human body altogether as subject matter, turning his attention to supersensory phenomena.

“Sequence 36.1-36.5,” 2010, black & white, silent video, 8:42. Courtesy the artist and Horton Gallery, New York.

For more information about the show, visit Horton Gallery.