Now that we live in a world where everybody is a hipster, that means that nobody is a hipster anymore, because by definition, to be a hipster means to partake of a kind of elitism that is really a hypercanny anti-elitism. That older idea was a very different thing that the current go-with-the-flow postures of placid hipsterism that flavors the Facebook generation’s epidemic of terminal self-infatuation. Today’s hipsterism only succeeds in using a barrage of selfies, hashtags and emoticons to drown out the few moments of uncanny criticality that we have left to us, creating a kind of psychic death-by-a-thousand-likebutton-hits. Now, there no longer is any point in trying to beat back the rising tsunami of hipster self-congratulation, because, like the power it so poorly pretends to mock, it is far too is diffuse and omnipresent to even name. And to make matters even worse, what now passes for hipsterism has also been completely commandeered as an instrument of that power, insofar as it has the ability to alchemically turn posture to equity and back again, creating many different forms of gentrification along the way.

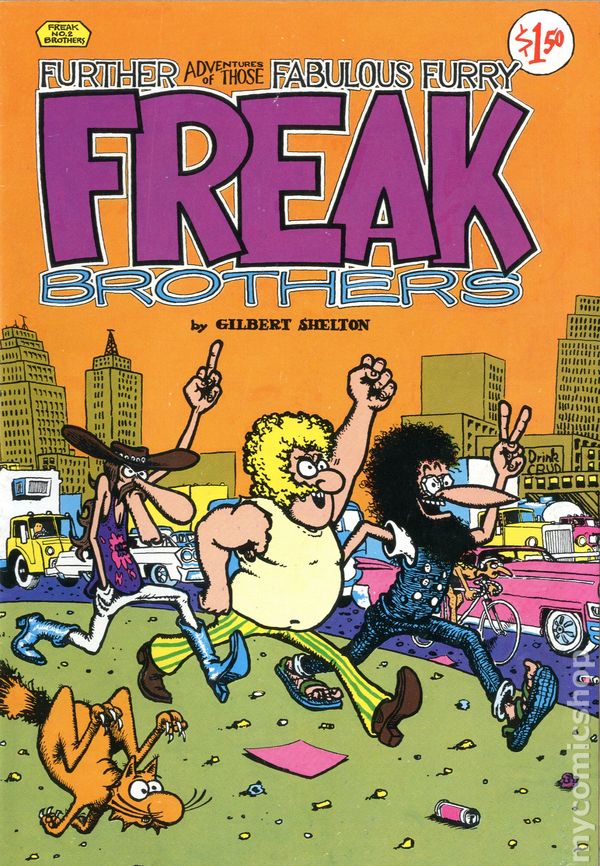

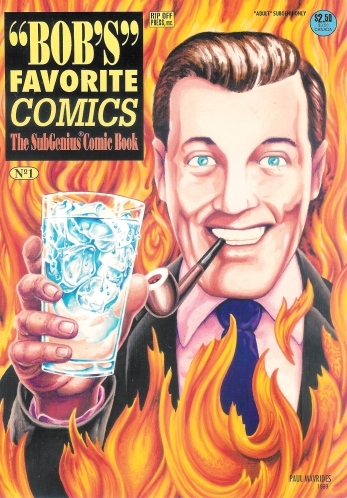

This bitter preamble sets the stage for what I now want to proclaim, which is that in a world where the self-trivializing narrative of hipsterism is everywhere, the real deal may not be immediately apparent, so when we find it, loud celebration is in order. Paul Mavrides’ current exhibition at the Steven Wolf Gallery is a perfect case in point. Mavrides work comes to us fully buoyed by unimpeachable hipster cred that was earned the old fashioned way during a time much different than our own, that being the time when being a hipster still mattered. His resume is one for the ages: during the early 1970s, he was a member of the Zap Comix collective, and with Gilbert Shelton he co-authored “The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.” 1979, he was a confounder of “The Church of the Sub-Genius” with Ivan Stang, Philo Drummond and Monte Dhooge, that being a Dallas, Texas-based group that created an underground publishing empire around a wickedly elaborate anarcho-libertarian theology satirizing religious fundamentalism, conspiracy theories and new age moronicism. The early “Subgenius” books were full-out graphic novels that used fanciful mélanges of pre-digital clip art to chronicle the exploits of J.R. “Bob” Dobbs, a salesman-turned-prophet who preached the doctrine of slack at the very beginning of the so-called Reagan revolution which was consecrated to everything else. Given Mavrides Zap Comix background, it is fair to assume that Mavrides’s association with the church had much to do with the development of its elaborate graphic materials, but many others also contributed in the area, most notably R. Crumb.

Installation view of “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990’s” at The Temporary Contemporary at MOCA, January 26 – April 26, 1992, photo by Paula Goldman, © The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Installation view of “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990’s” at The Temporary Contemporary at MOCA, January 26 – April 26, 1992, photo by Paula Goldman, © The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

I bring up the “Subgenius” episode because of the unacknowledged influence that it exerted over much of the art production of the 1990s. The official narrative of that decade has it that Paul Schimmel’s “Helter Skelter” exhibition (held at LA MOCA in 1992) established a new legitimization of so-called low brow esthetics that carried through most of the decade, but that exhibition also called into question the appropriation of various forms of Pop culture illustration that further blurred the boundary between entertainment and art. By 1998, the style had a name, and that name was Pop Surrealism, reminding us that at that time, technologically-enhanced popular media had grown exponentially stranger than post-NEA artworld art. Almost 20 years later, Pop Surrealism seems to at last be running out of gas, but history is history, and the mythomaniacal clip-art orgies that Mavrides concocted for several of the highly entertaining “Subgenious” books still seem to sustain a spot-on freshness lacking in most of the after-the-fact art featured in Juxtapose.

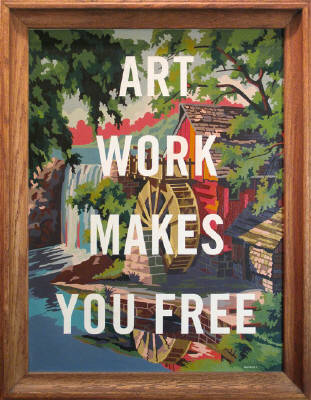

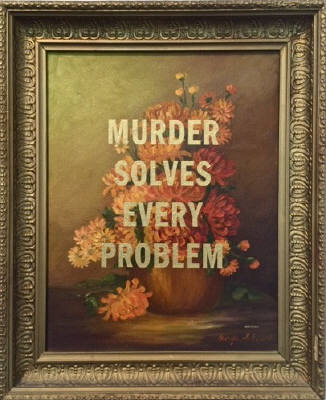

The exhibition under examination here contains nothing related to Mavrides’s “Subgenius” works, but they do reveal some similar strategies. It is important to note that the 27 works on view in this exhibition span a full decade of production, sporting dates that run from 2004 to 2013. The majority of these rely on the repurposing of a familiar type of found-object, those being mass-produced oil paintings of saccharine still lives and bucolic landscapes, almost all contained in tawdry picture frames. None of these paintings are remarkable in any way, and in fact, prior to Mavrides’s manipulations, they were far less remarkable then Thomas Kinkade’s work, if you can imagine what that might look like.

Marvides strategically improves these works by hand-painting large text fragments over the pictures, usually in either a block or mock-Helvetica font. It is easy to be a bit startled by the fact that we do not see hand-painted lettering anymore, and this is exacerbated by the fact that there is obviously much more care taken in the lettering than was ever at issue in the manufacture of the original paintings. But there are other startling aspects to the lettering, not the least of which is what the words made from it actually say. For example, it a 2005 work from which the exhibition’s title is taken, we see what looks to be a paint-by-numbers rendition of a water mill set in autumnal colors. Emblazoned over the image is the phase “Art Work Sets You Free,” an anglicized harking to the Germanic “Arbeit Macht Frie” slogan that adorned Second World War death camps. Two very different still-lives of the same size are featured parts of a diptych from 2004 titled “I Love You More than Life Itself/ Fuck You You Fucking Fuck.” And lest we forget, “Murder Solves Every Problem” is the phrase that hovers over another small work that starts with a conventional still life.

Not all of Mavrides’s works feature sardonic verbal components deftly painted over the manufactured iconography of cheap cheer. The earliest work in the exhibition is titled “Two Guns” (2004), featuring a pair of revolvers spelled out in black schematic line. Additionally, there are some other works painted on black velvet in garish semi-fluorescent colors. One of these shows the iconic version of Jack Ruby’s fatal shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald, this painted in a spirit similar to how we might expect to see a quartet of dogs playing poker. Another work takes an equally iconic image, in this case, the Challenger disaster, and turns it into posh décor tinctured with laughter that sticks in our throat.

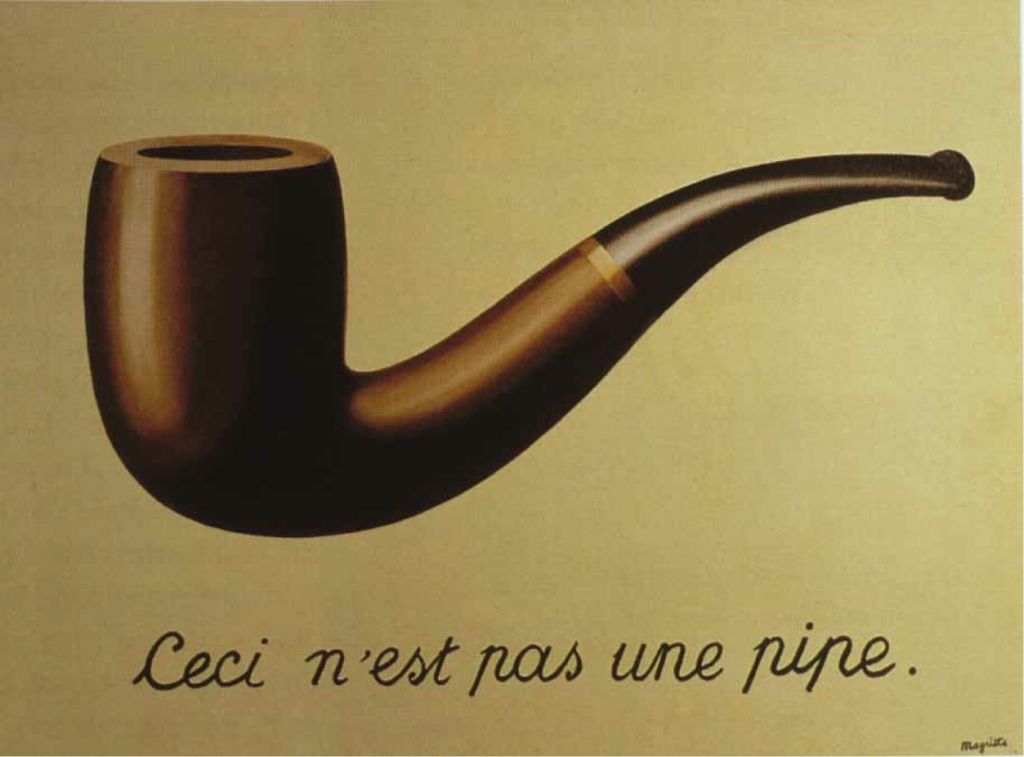

As any one who has trolled their way through the art world now knows, the addition of text to a picture surface is a fairly familiar device, going back to Rene Magritte’s painting of a pipe titled “The Wind and the Song” (1928). One also thinks of Ed Ruscha’s word paintings from the 1970s, and Barbara Krugar’s photomontages from the 1980s, but there is something delightfully more bitter about Mavrides’s work. I write this not because those other artists were also responding to their experience of being an American, but instead because the Mavrides’s works mourn something besides the passing of the American dream into a cloud of anestheticized fantasy. That other thing is nothing less than the passing of the hipster dream that may have been the last remnant of its older cousin, now recognizing too late that it too cannot survive the transition from nation states to banking networks that governs our destiny.

For more information visit Steven Wolf Fine Arts, San Francisco