By John Held, Jr.

On August 10, 1988, I found myself laid out in a wetsuit atop a plank of wood in Sennan Art Village, somewhere in Southern Japan. I was wearing a respirator, while being spray painted by Shozo Shimamoto, a former member of the Gutai art association, who had arranged a series of performances throughout the country for a group of artists from Italy, France, Japan and the United States, drawn together by their interest in Mail Art. We had come to commemorate the victims of Hiroshima, performing there on August 6.

While Shozo was spray painting around me, leaving a shadow where I would later stencil in words, surrounded by curious children, I had no idea that this was in perfect keeping with the Gutai tradition of art arising from concrete, or performative actions. Yes, I knew of Shozo’s past history in Gutai, and met members of the group, including Yasuo Sumi and Teruyuki Tsubouchi. But Shozo never mentioned this, nor did he refer to the wetsuit and respirator I was wearing, which unconsciously mimicked an outfit Shozo wore thirty years before, when he performing his “bottle crash” activities.

But in the 1980s, there was little information about Gutai in the English language. Exhibitions on the movement were just beginning to occur in Japan, as well as Germany (1983) and Spain (1986). It remained until 2012 that the first Gutai museum exhibition would be held in Tokyo, and not until 2013, when the Guggenheim mounts, Gutai: Splendid Playground, on February 15, will there have been a full blown survey of Gutai in an American Museum.

One of the great figures of the Japanese post-war avant-garde, Shimamoto studied with artist Jiro Yoshihara in 1947 and became an original member of Gutai when Yoshihara formed the association in 1954. Shimamoto was the individual who proposed the name Gutai (meaning “concrete”), which the membership adopted. He was also the first editor of Gutai magazine, which was printed in his home. Gutai was a precursor of “happenings,” and viewed art as process.

Shimamoto became known for making art out of “destructive” acts – firing a handmade cannon filled with paint at a large sheet for an outdoor exhibition, hurtling bottles of glass bottles leaving both paint and glass on the canvas, breaking lit light bulbs at the seminal presentation, Gutai on Stage, in 1960.

Shortly after the dissolution of Gutai upon the death of Yoshihara in 1972, Shimamoto formed AU (Art Unidentified and/or Artists Union) art group in 1975. In 1982, Shimamoto became aware of Mail Art through Byron Black, an expatriate American living in Osaka. Since then, Shimamoto has been an active participant in Mail Art, organizing exhibitions throughout Japan, hosting the visits of international Mail Artists (including my own visits in 1988 and 1993), and traveling the world to meet other Mail Artists. His work has been increasing recognized by major museum exhibitions, including Scream Against the Sky: Japanese Art After 1945, shown at the Guggenheim Museum (1994-1995) and elsewhere.

His progression from Gutai to Mail Art, stressing collaborative art and art as process, is a cornerstone of Mail Art’s claim to a rightful place in the twentieth century avant-garde. He himself claimed that, “What inspired me and encouraged me most in this effort was ‘Gutai’, whose spirit is embodied in the activities of ‘mail art’, a form of expression campaigned for by the Artists Union today.”

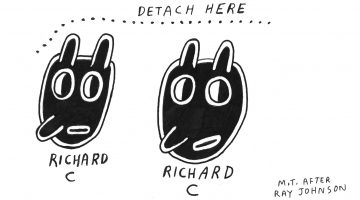

My first letters from Shimamoto date from 1986. Twenty-five pieces of his correspondence to me, dated from 1986 through 1994, were donated to the Archives of American Art. Although Shozo was unaware of the Mail Art network before meeting Byron Black, he had been in touch with the “father” of Mail Art, Ray Johnson, as early as 1957, when Johnson contacted the group after having been given an early issue of Gutai magazine. Johnson’s innovative use of the postal system enthralled the Gutai group, who not only reprinted his correspondence, but emulated his creativity in their own mailings, most notably in the production of Nagano, or New Year cards.

After the dissolution of Gutai following the death of Jiro Yoshihara in 1972, Shozo Shimamoto began his own art association, AU (Artist’s Union and/or Art Unidentified), which published a frequently issued newsletter widely distributed to the international Mail Art community. In 1986, Shozo shaved his head in honor of a visit to Japan by the Italian Mail Artist Guglielmo Achille Cavellini. Shimamoto continued using his bald head as a canvas for artists to do on what they wished, traveling widely to perform these actions in the United States, Europe and Soviet Union. In 1987, Shozo traveled to Dallas, where I was then living, to perform his “Networking on the Head,” activity with myself and other local Mail Artists at the Dallas Museum of Art, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Marcel Duchamp.

Shozo continued his activities on behalf of peace by joining with Native American activist Dennis Banks, in a run across Europe in 1990. Along the way, Shimamoto was joined and supported by Mail Artists. Gutai had reached out to the world through Gutai magazine, their association with French art critic Michael Tapié, and hosting artistic dignitaries such as John Cage, Jasper Johns, Pierre Restany, Yoko Ono, Clement Greenburg and others at the Gutai Pinacotheca in Osaka.

Shozo was a professor at Kyoto Educational University and the Principal at a school for handicapped children. His concern for children and the physically challenged remained a constant in his life. In 2007, he traveled to Beijing, where he helped organize the Art Challenged project for disabled artists. More information on his recent activities can be found at shozo.net.

On February 8th, the San Francisco Art Institute will open the first West Coast survey exhibition on Gutai, co-curated by Andrew McClintock and myself (http://www.sfai.edu/event/gutai-historical-survey-and-contemporary-response). In early 2012, we issued a notice to the Mail Art community of a Mail Art exhibition to honor Shimamoto and Gutai. One hundred and seventy-five plus artists from thirty-five countries responded, interpreting historic Gutai in contemporary expression and honoring one of their own.

Little did we know that just two weeks before the opening of the exhibition, Mr. Shimamoto would pass away on January 25, 2013, just three days after his 85th birthday. His full legacy remains to be revealed, but from limited recognition in the 1980s, Shimamoto’s stature has risen to the extent that (former) Los Angeles MOCA curator Paul Schimmel, has enshrined his work in the current exhibition, Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949-1962, devoting a room in the exhibition to the works of Shimamoto and Robert Rauschenberg.

Shimamoto set out not only to “destroy the picture,” but to destroy the notion of artist as solitary creator. Shimamoto’s philosophy has always been one of inclusion, be it children, the physically and mentally challenged, or a worldwide network of artists sharing interests and information. His formative years in Gutai prepared him for leadership in AU, an artist cooperative that reached out to the world through publications and collaborative actions. He is missed by a younger generation of artists, who he encouraged and inspired.