If you’re in London and not doing the fun stuff like eating curry in Shoreditch, buying Ketamine in Brixton or brown-bagging beers in Camden (brown-bagless, of course), the annual Turner Prize awaits your amusement at Tate Britain.

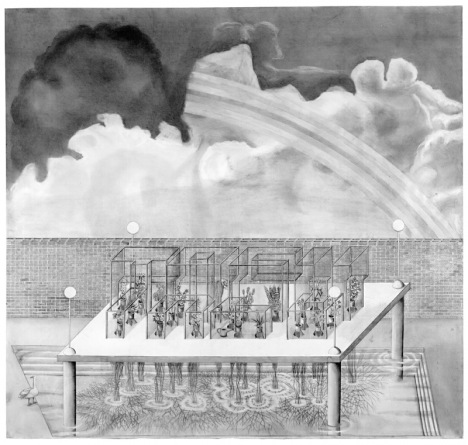

Refusing to pay for special exhibitions, I loitered around the entrance until the ticket collector was distracted enough to allow me a chance to sneak into the first gallery of the exhibition. Paul Nobel’s massive pencil drawings display other-worldly landscapes with geometrical constructions. The work is tedious, with an attention to detail that makes it feel mechanical yet riddled with organic formations. From a distance, the drawings are like strange gardens with architectural insertions reminiscent of Hedge Mazes, kind of like the one in The Shining where Jack Torrance, the lead bad guy, gets lost and dies in. The drawings create a labyrinth where fantasy and reality break down and new dimensions and worlds open up, or maybe close in.

These massive drawings seem more like monumental miniatures, with the buildings literally spelling out subjects with a typeface he invented called “Nobson”. The blocky lettering constructs his imaginary city block by block, giving hints and clues to piece together a dream-like puzzle of otherwise nameless locations. Paul’s work leaves the viewer feeling a little helpless, trying to make sense of what the hell it is we are suppose to see, or read. But perhaps that’s a good thing, offering stories not to tell, but to witness.

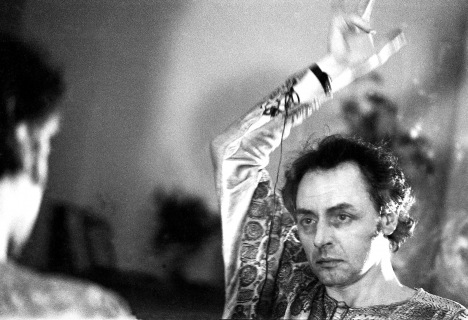

Luke Fowler’s photos and films explore psychiatry, social norms, tradition and mainstream societal conventions. The work is heavy on research and intellectual groundwork that make it complex but he pays delicate attention to form and presentation. The photoworks currently on display are mostly diptychs, with opposing images placed side by side to suggest a certain era, or atmosphere. The subjects are sometimes obscured by light or reflections, with objects, people and places sharing a theme or relation.

Luke Fowler, All Divided Selves 2011 Courtesy of the artist, The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Luke’s film All Divided Selves (2011) is the last of a trilogy with fellow Glaswegian (I can honestly say I have never said or typed that marvelous word) RD Laing as its subject. Laing is considered to be a pioneer of the “anti-psychiatry” movement who challenged orthodox psychiatry of his time and purported mental illness, such as psychosis, as not a mere biological phenomenon but rather a personal state with social, cultural and emotional significance. He was also a raging alcoholic and political lefty, and at one point in All Divided Selves, Laing is being interviewed in 1985 on a TV show when the host accuses him of being drunk. How Scottish! The crowd erupts in defense of their favorite Glaswegian (that makes it twice) psychiatrist, just as Luke guides us to additional scenes of patient hysteria. Luke’s work, from what I gathered, is about social and peripheral experience and how we each operate in creating collective representations.

Next door, I was nearly asked to leave after getting caught trying to bootleg Elizabeth Price’s film, which I fell madly in love with. But in a way she cheated, chopping up Shangri-Las’ signature song “Out in the Streets” throughout the film – I mean who doesn’t love the Shangri-Las? That’s like showing up to a party with free drugs, or bribing a kid with a banana split fudge sundae. Of course you will be loved. But you can’t hate the player, and The Woolworths Choir of 1979 (2012) is one of the most neatly edited and uniquely delivered films I’ve seen at the Turner Prize series.

Elizabeth stitches together archived news footage, found text and images while creating a soundtrack that is both appropriated music and fabricated audio. Drawing from popular culture, she bridges narratives of information that use historical contexts as footnotes to fiction.

The Woolworths Choir of 1979 is made up of 3 parts that essentially set the stage of a real life fire at a Woolworths in Manchester where 10 people were burnt alive. The film explores natures of “the choir”, with first a montage of photographs showing a church layout, where the ensemble of singers stand before the pews, or audience. Beneath the choir are almost demonic misericords carved into the benches, revealing contradictory imagery found in cathedrals while foreshadowing the iconic exchanges within the film. This leads into the very lovely, very chic, Shangri-Las, a collection of scenes that make up the meat of this sandwich, evoking both the church choir while alluding to the fire that follows. Dressed in all black and placed separately on singular stages, the Shangri-Las give a ghostly presence as they appear and disappear into blackness. Within the chorus they hum what sounds like drawn-out sirens, or a spooky wind, and they gradually and methodically raise their hands upward and downward as a priest would to summon the Holy Spirit. Elizabeth matches the band’s claps to the news footage of witnesses snapping their fingers to describe how quickly ablaze “It all went up”. She connects the body language and gestural movements of the band, the victim’s hands waving through windows that bellow smoke and the onlookers who described the event from out on the street. I might be wiping the fudge sundae from my lips but I found this piece to be cinematic choreography at its finest. The PRICE IS RIGHT.

In the final gallery is the very lovely Spartacus Chetwynd, whose work often blurs the boundaries between the audience and the performers through carnivalesque happenings. She uses mostly handmade props, costumes, sets and usually employs friends to execute her performances. On view is her most recent project, Odd Man Out (2011), in which a ceiling to floor paper installation depicts a sort of fifth ring of hell, with men being eaten alive by serpents or reptiles, as malicious fanged animals look on. As ominous music begins to rumble from the bowels of the Tate, performers emerge into the play-pin of anguish and toss around leaves as they stomp on the ground like restless explorers. They looked like jungle humanoids, kind of like that fucked up half-plant creature popular in the comic world, the Swamp Thing. They pull people from the audience to whisper to them semi-truthful vulgarities or omens, like “Your life is pathetic” or “You will lose your Oyster card”. They whispered to me, “75% of people have better sex than you.” Is it that obvious? Spartacus continues her DIY Fuck-You-But- Hey-Do-You-Want-To-Come-Over-And-Play legacy of improvisation and social critique in an always welcomed democratization of the art viewing experience. I really really want to break shit with her and stitch costumes…I’m toying with pick-up lines now. “Hey Spark, gotta light?”

The Turner Prize is on view at Tate Britain through January 6, 2013, with the winner being announced on December 3.

—

Dean Dempsey is a visual artist based in New York City who disguises perpetual neurotic complaining about everyday life as intellectual and artistic observations.