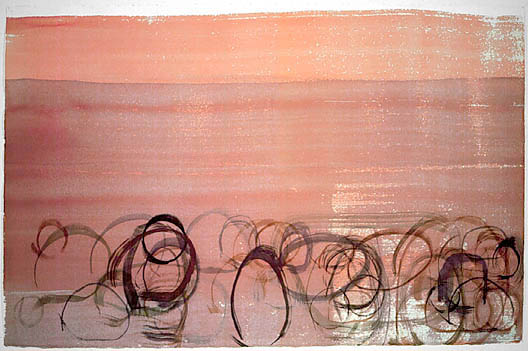

River rock and feather brush. From Ray Kass’ "The Sight of Silence: John Cage’s Complete Watercolors," published on www.johncage2012.com.

There are three types of white men who consult the I Ching: intellectual psychedelic drug-using Ken Kesey-types, owners of General Mao lamps, and John Cage. Cage is principally known for finding the beauty in chance, in music scores and, later, visual art. Some of that indeterminacy has come from using the Chinese divination system since the 1950’s (Austun, 20). Asking the I Ching questions is supposed to give the person throwing the I Ching coins insight into the cycles of life and foresight that will help guide their life toward alignment with the universe. Manipulating the coin’s head/tales outcomes into one of 64 hexagrams, each a different permutation of horizontal lines and lines broken in the middle. Decoding the hexagram reveals maxims and actionable advice, such as: “Kâu shows a female who is bold and strong. It will not be good to marry (such) a female” (Paranormality). Right. For Cage, throwing the I Ching was just another derivation of chance, as he told Stephen Montague in an interview in 1985:

I use the I Ching when it is useful, just as I turn on the water faucet when I want a drink. I find the I Ching useful to answer questions, and when I have questions, I use it. Then the answers, instead of coming from my likes and dislikes, come from chance operations, and that has the effect of opening me to possibilities that I hadn’t considered. Chance-determined answers will open my mind to the world around (212).

When Cage made art, the I Ching dictated how the compositional pieces were arranged and insight followed. He removed himself just enough, but evidently there was enough ego left for reflection.

John Cage New River Watercolor, Series IV, #4 1988 in "Wabi Sabi in the West" at A.V.C. Contemporary Arts Gallery, New York. 2012. Image from Artnet.

Manhattan’s National Academy Museum is currently exhibiting Cage’s paintings made in the 1980s and ‘90s using the I Ching, smooth stones, exotic feathers, watercolor, and what looks like backyard mud. Painted at the Mountain Lake Workshop in Blacksburg, Virginia, Cage used I Ching hexagrams to choose which of his numbered brushes, pigments, papers, and rock collection would be used in a painting, and where. Whether the “where” was determined by a numbered grid system or numerical relationships visible to a musician is unclear. Cage also created rules to avoid aesthetics he didn’t like, such as confining a rock’s placement to ensure the rock’s outlines wouldn’t go off the paper (Kass, 51). The resulting works are similar in theory to works like 1958’s “Aria”, where color-coded tones squiggle on a white page. “The white paper equals silence. (…) The marks themselves are like the occurrence of sound in music,” Cage explained (Ellis, 195). The paintings are just another visualization of Cage’s practicing theory of nearly all of his work, but it’s fun to see this stage in his expression.

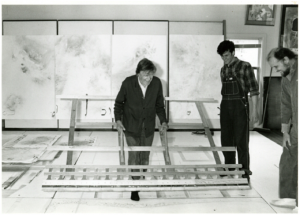

An even bigger brush. John Cage, Peter Lau, and Ray Kass. Image owned by Ray Kass and Virginia Tech Photographic Services. Via www.johncage2012.com.

The National Academy Museum also displays portions of event scores and 1969’s “Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel”; though, the sparsity of non-painting works and lack of textual explanations requires visitors to bring their own contextual understanding. The works were hung in non-sequential clumps, sometimes two inches off the baseboard, by “chance operations” (National Academy Museum). The highlight of the exhibit is a room of paraphernalia Cage used to create the paintings: a brush made of a bird’s wing tied to a stick, and enormous brush made up of eight flat brushes and its accompanying trough, and rocks of varying size. Cage’s tools are weird and delightful, and this may be the only time a rock collection is interesting to someone other than it’s collector.

“John Cage: The Sight of Silence” is on view at the National Academy Museum in Manhattan through January 13, 2013. There will be sixteen performances of Cage’s work, his contemporaries’ work, and those he inspired throughout the exhibition. See the full program listing here.

-Kendall George

Citations:

Austin, Larry, John Cage and Lejaren Hiller. Computer Music Journal , Vol. 16, No. 4 (Winter, 1992), pp. 15-29 Published by: The MIT Press. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3680466

Cage, John. “Interview with John Cage.” Interview by Simone Ellis. Conversing with Cage. By Ric Kostelanetz. New York: Routledge. Web 26 September 2012. http://biologos.org/blog/chance-creation

Montague, Stephen. “John Cage at Seventy: An Interview” American Music , Vol. 3, No. 2 (Summer, 1985), pp. 205-216. Published by: University of Illinois Press. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3051637

Image Sources:

Artnet. John Cage New River Watercolor, Series IV, #4 1988 in “Wabi Sabi in the West” at A.V.C. Contemporary Arts Gallery, New York. 2012. Web 28 September 2012. http://www.artnet.com/Magazine/reviews/karlins2/karlins7-31-1.asp

Reynolds, Roger. RAY KASS: JOHN CAGE’S WATERCOLOR PAINTINGS. John Cage Centennial Festival Washington, DC Site, 2012. Web 28 September 2012. http://www.johncage2012.com/features/watercolors.html