Ben Tufnell is the Director of Exhibitions for Haunch of Venison, London

Interviewed by Maria Nicolacopoulou

(From issue 10 of SFAQ)

“She was a pioneer artist of the time, but also the only woman within a macho environment. So despite being very well regarded, she has been overlooked…She was one of the first artists engaged in public art, but public art back then was not as ‘prestigious’ as it is today. Another important reason is that as Robert Smithson’s widow, she has worked very hard to protect and promote his legacy…”

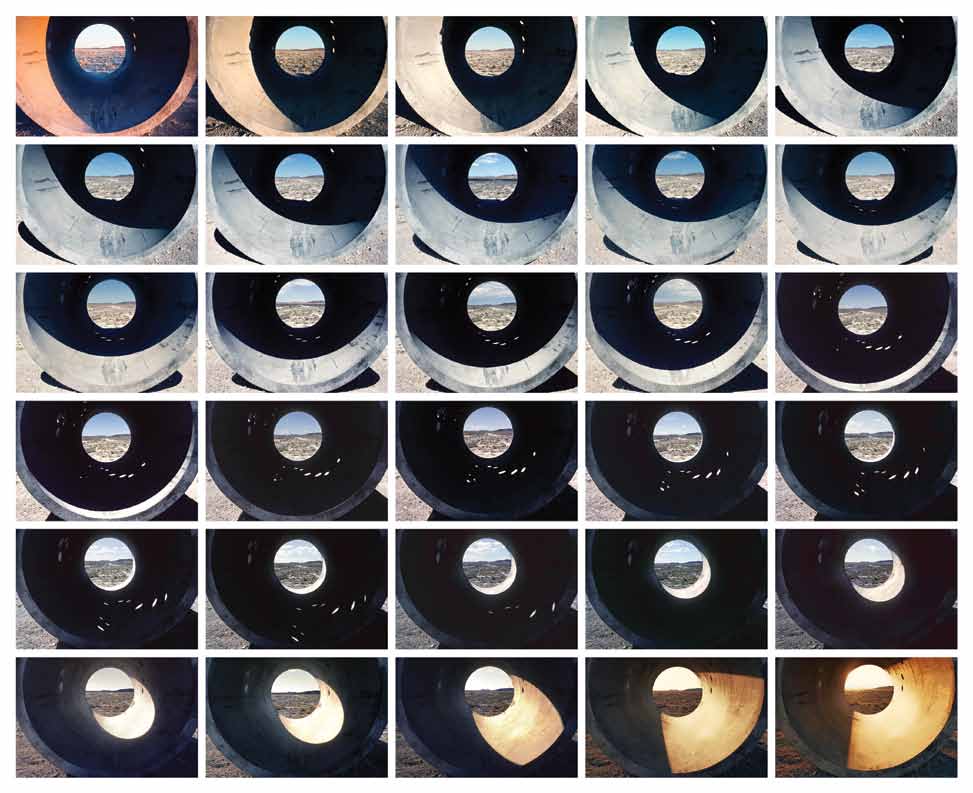

Nancy Holt, “Sunlight in Sun Tunnels”, 1976. Composite of thirty photographs of sunlight and shadow in one tunnel photographed every half hour from 6.30 AM to 9.00 PM in 14 July 1976 Composite inkjet print taken from original 35mm colour transparencies; printed on archival rag paper 2012. 127.3 x 156.2 cm © Nancy Holt. Courtesy of Haunch of Venison.

Highly influential and central to site-specific art, Land Art was a vanguard art movement that began in the 1960’s as a response to a variety of social and political upheavals. Various initiatives, projects and exhibitions taking place around the world today are reevaluating the movement’s relevance on contemporary terms.

On the occasion of Nancy Holt’s first UK solo exhibition: Photoworks, presenting a range of work from 1967 to 2007, much of which has never been exhibited before, I sat down with curator and director of exhibitions for Haunch of Venison, Ben Tufnell. My goal: to investigate the relationship between the movement of Land Art, within the context of a gallery as well as to explore the relevance of that movement and Nancy Holt’s work, through historical terms and contemporary culture.

Before joining Haunch of Venison in 2006, Tufnell was a curator at Tate where he organized many exhibitions, including: Hamish Fulton: Walking Journey (2002), the Turner Prize (2000, 2003) and the Art Now series (2004-06).

His writings have appeared in a number of publications, such as Modern Painters, Art Review and Contemporary, as well as catalogues published by Tate Britain, Tate St Ives, Museo Universitario Arte Contempopranea, Mexico City and the Henry Moore Institute, among others.

His books include Land Art (Tate Publishing, 2006) and Richard Long: Selected Statements and Interviews (Haunch of Venison, 2007). He is currently working on a survey exhibition of Land Art in Britain 1966-79 for the Arts Council, which will tour British museums 2013-14.

Before we start, tell us a little bit about yourself. What made you join a commercial gallery?

I was a curator at Tate Britain for nine years before joining Haunch of Venison. It was in many ways a surprise to find myself in a commercial gallery, but the key thing was that I had the opportunity to work closely with Richard Long. And to be honest, it’s been possible use the platform offered by a gallery like HoV to work with some really great artists and make some ambitious exhibitions which I couldn’t have done otherwise. I’m a curator, not a dealer, but I understand that if you make great shows with great artists the commercial side of things should take care of itself. It always has to be about quality.

What were the reasons behind your decision to exhibit Nancy Holt?

Her work is a natural fit for our program based on the artists we already represent: Richard Long, Giuseppe Penone, Thomas Joshua Cooper, among others. Alena Williams, the curator of Sightlines [Nancy Holt] initially organized for U.S. venues, starting with the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in 2010, followed by the Graham Foundation, Chicago, which is currently on display at the Santa Fe Art Institute, made the introduction. I tried to help Alena find a U.K. venue for that show, and when it didn’t work out we began a discussion with Nancy about doing something with HoV in London. Nancy’s work should be better known and should be in major collections. Hopefully we can do something about that. It’s an interesting challenge.

Do you think that being a woman was the reason her work has not been as prevalent as that of her male peers?

Definitely. She was a pioneer artist of the time, but also the only woman within a macho environment. So despite being very well regarded, she has been overlooked – for example, she is currently almost completely unrepresented in museum collections, so she doesn’t figure in the stories of late twentieth century art that those museums tell. It could also be because she was more focused on public works than making art for galleries. She was one of the first artists engaged in public art, but public art back then was not as ‘prestigious’ as it is today. Another important reason is that as Robert Smithson’s widow, she has worked very hard to protect and promote his legacy, which, in itself, was a very time-consuming task.

Land Art is said to have been important for taking art out of the gallery or museum and into the natural landscape away from the “corrupted” urbanity of the time. How does the work’s media nature and its repositioning back within the context of a gallery affect the work, along with what Land Art represents as a movement?

First of all, it is important to separate the work from the actual landscape. There are issues of accessibility which render documentation necessary. Of course the site is different to the description of the site, yet very few artists make work in the landscape that they don’t afterwards bring into the gallery in some way. Documenting the work is, I believe, intrinsic to its dynamic and certainly doesn’t compromise it. If anything, it brings a different aspect of the work to how we experience it in the landscape. It is, in a sense, two different sides of the same argument.

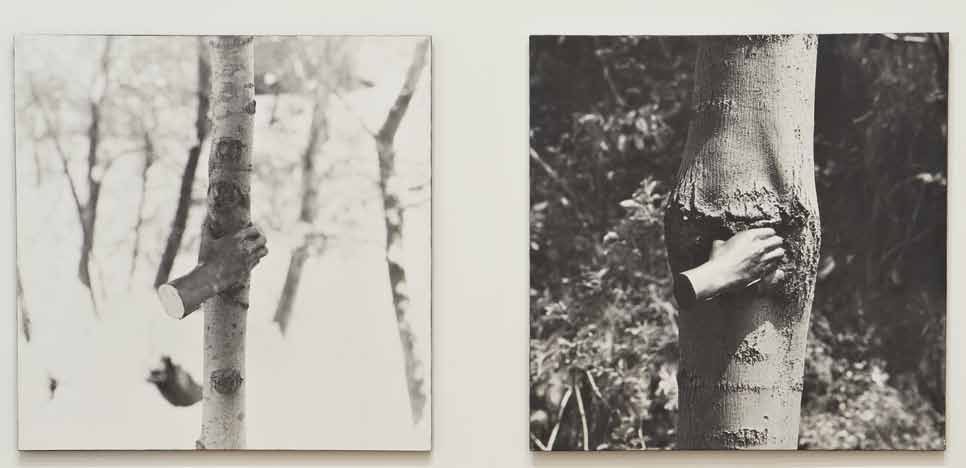

Giuseppe Penone, “Alpi marittime - Continuerà a crescere tranne che in quel punto”, 1968-78. 2 black and white photographs on canvas. 84.5 x 84.5 cm each. ©Giuseppe Penone, Photograph by Peter Mallet, Courtesy Haunch of Venison.

How could we then separate documentation of Land Art to plain documentary or landscape photography?

I guess it’s hard to be definitive about that and every artist approaches it differently. Nancy’s approach, for example, can encompass both approaches. She makes work using multiple components rather than a single view, which testifies to the presence of the artist’s experience within the landscape. In that way, she’s going against conventional representation of the landscape, and with different framing techniques she represents movement while rejecting the single definitive view with its associations to the venerable tradition of landscape painting – or indeed ‘classic’ landscape photography. (photo: over the hill) On another note, Richard Long says that his sculptures in galleries are there to stimulate the senses through a raw and visceral experience. His photographic works offer a different kind of engagement: they stimulate the imagination, taking us to remote places.

Public art is usually the product of a commissioned initiative whereas Land Art is the product of an artistic intervention within the natural landscape, yet these two terms seem to often overlap. How do you think it is possible to keep the two separate, if at all?

Coming back to Nancy, we can differentiate between her own initiatives such as the Sun Tunnels (sun tunnels photo) and her public commissions; one is created to a brief, for the public and the community, and the other is her own artistic initiative. Although both use a similar process in being site-specific and responding to a place, the conditions are different. It might be, for example, that work can be created as a personal initiative, but remain hidden and, therefore, private. An example of this might be Richard Long’s works depicting sculptures in landscapes, where nobody knows where the location is, only that a stone line or circle is somewhere in Africa or South America. So not all land art is public. Here again we see the alternative aspect that the medium of photography/media brings to the work that would have been otherwise impossible. Another example would be Giuseppe Penone’s work from the 1960 -70’s, where we are dealing with smaller scale and more intimate works in nature, which brings a completely different approach to the landscape. (photo: penone)

Certain views on public art claim that it is the only true art, due to, among other reasons, its distance from the art market and its inability to be traded. Do you think this element and the association of Land Art to public art prevents Land Art works from becoming commercial? Or does it have the opposite effect by adding value to the work?

Interestingly enough, all of the major earthworks projects in the U.S. were funded by private patrons or the artists’ dealers. Robert Smithson made an amazing film documenting the creation of the Spiral Jetty, which was then shown in the Dwan Gallery in New York. Again, we go back to the importance of the works’ media aspects here, in that it is not only bringing something relatively inaccessible to a wider audience, but eternalizing an ephemeral process while adding value. Turrell’s Roden Crater project [1] is another example of a funded work, and is also, incidentally, connected to Nancy’s work in being about ideas of light, relativity and cosmic scale. With regards the commercial aspects of such projects, Nancy Holt owns the land where the Sun Tunnels are located so, theoretically, she could sell the land and therefore we can say that work could be traded, but the work will always belong to the place. Not that would ever happen.

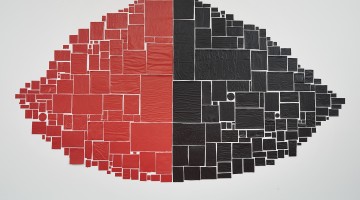

Nancy Holt, “Over the Hill”, 1968. Composite inkjet print on archival rag paper, printed from 16 original 126 format transparencies; printed 2012. 101.6 x 101.6 cm. © Nancy Holt. Courtesy of Haunch of Venison.

Where do you see Land Art progressing if we compare it to public art’s equivalent of “new public” art?

It seems to me that Land Art has great currency and vitality right now. It is being rediscovered by a new generation. As a genre it has reawakened due to current and ongoing environmental issues, so the need and demand to reconnect with nature is a major factor. And there are many young artists working out of the legacy of Nancy’s generation and doing just that. Artists such as Andrea Zittel and Katie Paterson, for example, present a contemporary approach to the land and the cosmos, and while their work carries echoes of the past, it engages with current issues and concerns.

[1] http://rodencrater.com/