Queen’s Nails

I’m so Goth…I’m Dead!

August 3-September 15

3191 Mission Street

S.F, CA. 94110

Front Space Installation - foreground Andrea Bacigalupo, Cleave 2012 background Manuel Ocampo, Islamic Disco, 1993

PLAY DEAD

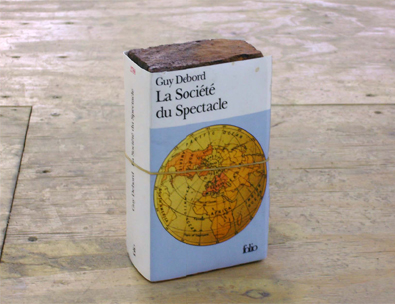

There is nothing dead in the ambitious new group show at Queen’s Nails—in fact, it’s writhing with life. It compels us to leave the gallery ready to hurl Claire Fontaine’s “La Societe duSpectacle Brickbat, 2006” –a brick wrapped in Guy Debord’s book cover and one of the selected works—through a metaphoric storefront window. “I’m so Goth…I’m Dead!” is a dead-on call to action.

Resisting anything more than a laconic one-line curatorial statement—“An exhibition based on the decline of spirit, collapse of economy, Gothic architecture and Goth culture”—artist-curator team Bob Linder and Julio César Morales, who studied at the San Francisco Art Institute together in the 90s and are now running Queens Nails’ exhibition program, have eschewed a selection of easily clichéd gothic-themed representations. Hell no…you won’t find a proliferation of abject, vampire or David Bowie images with sounds of Bauhaus playing “Bela Lugosi is Dead” here!

Instead, Linder and Morales have selected an eclectic mix of serious work, ranging in decades and media, offering up more oblique and penetrating interpretations of the seemingly inexhaustible trope. “I’m so Goth…I’m Dead!” convinces us that the “gothic” is much more than just a passing era-defining cultural trend bubbled up from an underground subculture that spanned innovation in art, music and fashion.

Still alive in my memory is Linder’s darkly humorous black coffin ceiling piece from 2002 BAY AREA NOW 3 at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts entitled “Bring the Fun Back!” which may very well be a key to the show’s curatorial vision. Queens Nails newly revamped gallery space creates an initial gothic landscape from the Mission Street façade looking in. Beginning with Andrea Bacigalupo’s skewed concrete and pigment obstructionist Gothic arch sculpture, one moves through the space and around her giant rib-bone-like floor pieces, ending at the horizon line with Manuel Ocampo’s 1995 sardonic “Islamic Disco”, oil on canvas skeleton dance.

More recent works like Nate Boyce’s guillotine-esque sculpture “Untitled, 2012” made from steel, epoxy clay and acrylic and Jason Jägel’s “Plans for The Future, 2012” a gouache of brightly colored silhouettes over war image newsprint allude directly to the mechanisms of death. Indeed, the show’s initial concept was organized around Anne McGuire’s 1996 video “When I Was a Monster,“ made in the aftermath of a near- fatal accident, in which the artist sits naked on a chair with her forearm braced by a mechanical medical contraption. Accompanied by a steady, droning B52s soundtrack the video culminates with McGuire trembling and falling back in her chair, in an ugly mimesis of death, like a grotesque surrealist automaton.

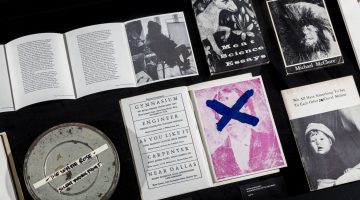

Morales’ music-centric curation is also at play in Juan Luna’s stack of Goth music compact disks and Joshua Churchill’s “Induction 2012” site-specific sound and electronic interventions. To note: the earliest significant usage of the term (as applied to music) is attributed to Joy Division’s producer in 1979 describing Joy Division as “Gothic” compared to the pop mainstream. In the same year, David J. Haskins, the bassist for the goth rock band Bauhaus created a series of “Paste-Ups”, newspaper clippings from Gary Gilmore’s notorious execution by firing squad on January 17, 1977. Haskins collages are formed with repetitions of prescient words for the 80s: “TV, Murder, TV, Technology, TV, Media Circus, TV, Methylamphetamine. ”

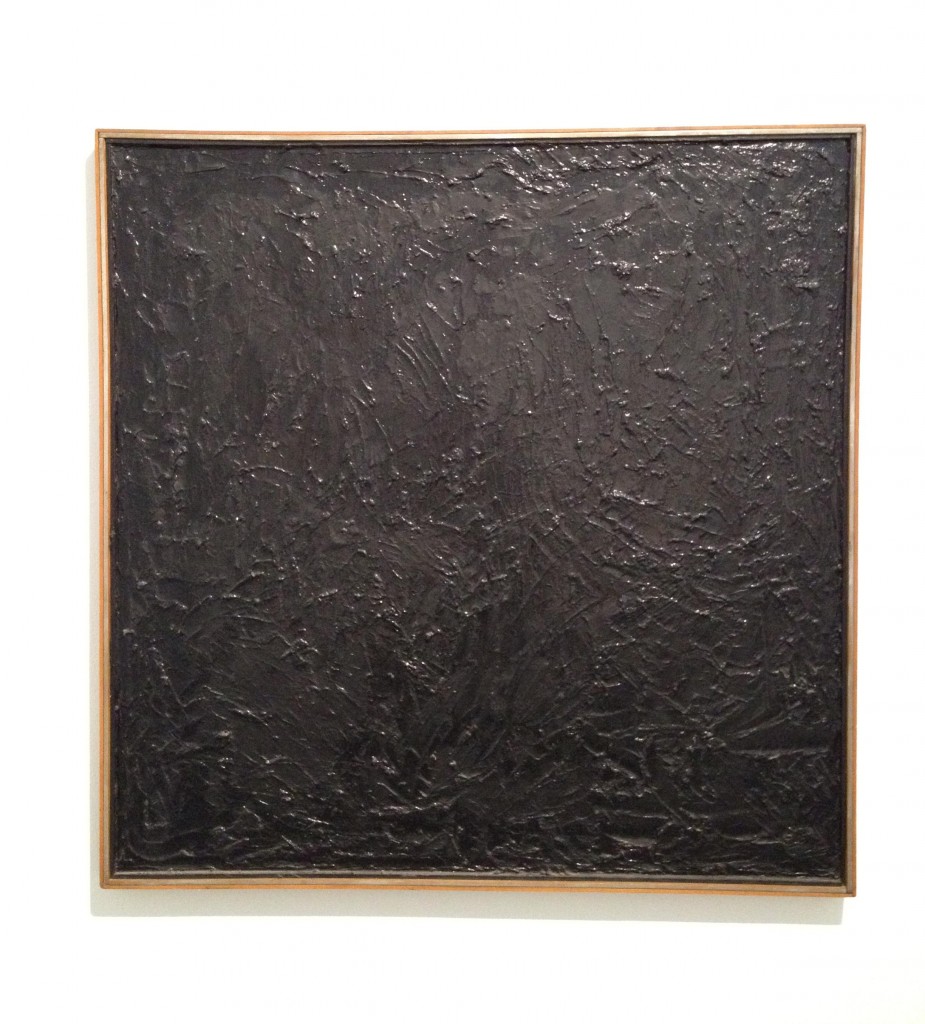

In the second gallery it’s Wally Hedrick’s drop-dead (excuse the pun) 48”x 48” black painting “Vietnam Series III, 1967″ which confidently secures the political and aesthetic premise of the show. The Black Paintings were Hedrick’s protest against the Vietnam War in which he took about 50 of his early canvases and painted them in heavy layers of black oil paint. Hedrick’s Black Paintings culminated in 1967 with “War Room”—an installation of a group of four eleven-by-eleven foot black canvases, each filling a wall of the room facing inwards, then arranged into a square in the shape of a room with an entry door.

One wonders if Linder and Morales are referencing Hedrick’s Six Gallery subculture hub and his gallerist-artist role as a precedent to Queens Nails and their own artist and curator practice? You could easily imagine a Pedro Reyes “Epitaphs” project being made in the Beat Six Gallery. “In this therapy participants are given a chance to write their own epitaph in plain or poetic language, ” writes Reyes, for this take-home instruction card. “Once you have completed your lettering you may place your epitaph in the “cemetery.” Keep the second for yourself.” This is why we want artists to curate.

But for me, the literal and figurative Gothic cornerstone of the show is a discreet piece by the collective Claire Fontaine —a printed cover of “La Société du Spectacle” wrapped around a brick on the main gallery floor. This paradoxical statement on Guy Debord’s seminal Situationist bible– associated with the 1968 student revolution first published in 1967 –shows how a once potent text has become ineffectual, laden by a lack of political action and too much academic veneration. It is in fact dead weight–an ancient manuscript for the walking-dead.

Claire Fontaine clarifies her position as an artist collective in this way: “We are like any other proletariat, expropriated from the ‘use of life’, because for the most part, the only historically significant use we have comes down to our artistic work.” Now that, dear reader, is what I would call, “Goth.” ###

___________

With Justin Adian, Juan Luna-Avin, Yason Banal, Andrea Bacigalupo, Nate Boyce, Enrique Chagoya, Joshua Churchill, Wally Hedrick, Desiree Holman, Claire Fontaine, Jason Jägel, David J. Haskins, Bessma Khalaf, Euan MacDonald, Anne McGuire, Manuel Ocampo, Eamon Ore-Giron, Suzy Poling, Erin Thurlow, Pedro Reyes and Jonathan Runcio.

Curated by Bob Linder and Julio César Morales

Natasha Boas Ph.D is a San-Francisco based curator, writer and professor of contemporary art. She has been curating internationally for over 20 years and has contributed to numerous publications and catalogues. She has taught at CCA, SFAI and Stanford and Yale Universities and is currently the curator at MOCFA in San Francisco. Her most recent exhibitions include “We They, We They: Clare Rojas” , “Only Birds Sing the Music of this World” with Harrell Fletcher and “E is for Everyone: Celebrating Sister Corita.” Boas’ essay “Was There Ever Really a Mission School: A Partial and Incomplete Oral History” is published in the current BAM/PFA Barry McGee August 2012 catalogue.