Interview by Lucy Kasofsky

The Flatiron Building is a wedge, like a slice of cake, poised at the beginning of Sutter Street. I would say that it is a perfect location for the third incarnation of Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art. Located on the third floor, the gallery is perched high enough above the busy downtown to cut the street noise. The space is an immediate relief from the city; well lit, airy, and noticeably clean, everything appears to be in order here, which is more than can be said for what is happening a few blocks away. I am met by Alexis Mackenzie, who is both the Assistant Director of Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art, and one of the gallery’s talented artists. While she lets Mark Wolfe know that I have arrived, I get a second look at one of Sarah Thibault’s neon vases and like it even better up close; what I had assumed was an effect of the light is carefully applied paint. Mark greets me warmly and we go to sit and talk in his office.

Mark Wolfe, Founder and Director of Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art. Photo credit: Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art

LK: Can you tell me something about what you did before opening Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art?

MW: Sure- I’m from San Francisco. I studied literature and creative writing in college. After I graduated, I spent a lot of time living overseas, came back, actually went to law school and got a law degree. I worked as a lawyer for some time, and then in 2002 I left the law firm I was working at and wanted to go into business for myself, still doing some law work, but also showing art in a space we had procured in the South of Market area. And at that time the space was not a commercial art gallery per se, it was much more informal. It was actually—if you know 111 Minna, it was the top floor of that building. It was more, as I said, an informal space where we would show artwork of friends. And from there it sort of evolved, into more of a commercial enterprise, more into what it is right now.

LK: What would you say piqued your interest in art?

MW: If I went way back it would be a sixth grade history teacher who in a very traditional, drill sergeant-like manner made us memorize the titles, painters and dates of several hundred art works, primarily from the Renaissance. At the time it was very difficult, but we had to look at paintings and say who painted them and when, and what country they were from, and what the name of the painting was. But I think that actually was the seed that was planted, and from there I studied some art history in college. Like I said, I lived overseas a lot and I looked at a lot of art. And I began collecting long before I got into this business. If I had to pick a watershed moment, it would be in 1999 there was an interesting confluence of things going on here in San Francisco, the most salient of which was a retrospective of Francis Bacon at the Legion of Honor. I remember walking into the room there and feeling literally my knees starting to shake, the experience was so intense. There was also, that same summer, a retrospective of Bill Viola’s video work at SFMOMA. There was some work in there, particularly his older stuff that he was doing in the 70s, not so much the big monumental stuff that he’s doing now, that I found to completely expand my horizons on what could be art and what constituted art. Both of these really provoked a really intense, almost physical response in me. It was at that moment I sort of realized how much power art, and contemporary art in particular, had the potential to generate from one human being to another.

LK: When you say that the first exhibition space you had was an informal space, what do you mean by that?

MW: For those that remember, in 2002 it was the dotcom crash, and suddenly, literally almost overnight there was this glut of space South of Market. It would be as if all the start-ups and Facebooks and Twitters and what-have-you suddenly tomorrow shuttered their doors. You would find an enormous amount of open, flexible floor plan loft style space suddenly empty. The owner of the building on Second Street where 111 Minna is, had this 5,000 square foot loft that was sitting empty and he let us occupy it for virtually nothing just because he wanted some tenants in the building. It was only a two-year deal, but it was this big open space and we didn’t have a liquor license per se, but we would basically call friends who were artists, artists in the community whose work I admired, and I basically said, Look, hang your work up, we’ll keep it up for two months; we’ll have a big party, we’ll call it an opening, if anything sells, great, we won’t take a commission. It was really just a way to keep a steady flow of different kinds of art on the walls in this big space, and to have a lot of fun. It became much more of an informal sort of salon, but like many things, it was short-lived, and once the real estate market started to pick up, the landlord sent us packing. And we actually went from there to 49 Geary. We were in that building for five years before we came here.

LK: What was the transition like moving from the first space to 49 Geary? I would expect that those were very different environments.

MW: Shortly before our time in the Second Street space expired we sort of had our first taste of real sales. We had a solo show of a street artist, and this was back in 2004, right before street art and the Banksy phenomenon really sort of hit. A bunch of the work sold, and suddenly that planted the seed that we could actually do this as a business, not just as a side project. When we were asked to leave that building, we started looking around for similar spaces in San Francisco, and there was a big space in the 49 Geary building that at the time was not that expensive, opened up and was offered to us, and we decided why not? We went ahead and took it. It was a very different experience, needless to say, if you are familiar with that building. But it really marked the turning point from when we moved from an informal, socially-oriented, salon style space to one that was really a commercial art gallery.

LK: I imagine that you could predict a different viewership here, or at 49 Geary, than at the first space. This area attracts many international and short-term visitors. Would you say that this affects the type of work you exhibit at all?

MW: I would say no, to be honest. At 49 Geary, and to a lesser extent here on Sutter Street, you know, we do get a lot of tourists and a lot of art students, but to be perfectly candid, the relationship between walk-in visitors and sales for us has always been very small. In five years at 49 Geary, I think we made fewer than ten sales to walk-ins. And the commercial viability of the gallery really depends on the old-fashioned meet-and-greet, developing personal relationships, traveling a lot to art fairs, and just cultivating, as I said, relationships with artists, collectors, and others. So the benefits of having a steady flow of visitors is great, because part of your mission is you want to exhibit work by artists that you’re excited about, and you want people to see it. When you have foot traffic and visitors, regardless of where they’re from, those are people seeing the work, and hopefully being affected by it, so that’s obviously a very good thing, but from a commercial standpoint it’s less important than you might think.

LK: Do you maintain a strong collector base in the Bay Area, or would you say that most of your collectors are elsewhere?

MW: At this point, I’d say the collector base is about 60/40 with the 60 being outside the Bay Area, and 40 being in the Bay Area. We do art fairs, and we have done them for several years, and have found that the bulk of our collectors come from the contacts that we make there. We certainly do work with some artists here that have been around the city for awhile and have their own sort of fan base, but particularly in terms of introducing new artists, I find we are more likely to find collectors for the work outside the Bay Area.

LK: I was first introduced to your gallery at Art Market in San Francisco. What was that experience like for you?

MW: It was very professionally managed. Those guys, Max and Jeff, they’re very professional in the way they staged the fair. I thought it looked great; absolutely no complaints about how we were treated, and all the logistics went well. We did reasonably well. I think given that it was here in San Francisco, which is a very, very small city and a very small market as everyone knows, and given that there were two other nominally competing fairs taking place at the same time, I’d say we were very pleased. We did well. I wouldn’t say it was the same as experiences we’ve had in other cities, namely Miami and New York, but I would say it was as good, if not better, than what we had expected, and we would probably do it again.

Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art booth at artMRKT San Francisco, 2012. Photo credit: Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art

LK: Would you say that you have a favorite art fair?

MW: You know, it’s funny that you ask that. The fairs that we participate in, or that we would participate in, change so much over time. In any given year the most memorable, most interesting, most exciting fair, in Miami, for example, would not be the same the following year, because the management changes, the selection committees change, the galleries come and go, open and close, participate and don’t participate. It’s very difficult to predict which fair on any given year is going to be the most interesting. All that said, one fair that we’ve done in New York, called Volta, and what’s distinct about it is that it’s solo presentations only. You can only bring one artist. So it’s a very high-risk venture, but the result is that the fair is much more coherent and cohesive. It’s almost like you’re going to a building like 49 Geary or you’re walking through Chelsea and seeing a bunch of solo shows at different galleries, that’s really what it is. So, I love going to that fair and I love participating in that fair even though it does carry more of a financial risk when you can only bring one artist, which, by the way—the fair organizers select from your roster.

Jordan Eagles, BARC 5, 2011. Blood, copper preserved on plexiglass, UV resin. 40 x 20 x 3 inches. Photo credit: Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art

LK: I am interested in the variety of work you exhibited at the fair. Between Sarah Thibault’s sculptural neon vases, Gudrun Mertes-Frady’s works on paper, Todd Lanam’s colorful paintings and Jordan Eagles’ work on plexiglass, there was work in a broad range of media and scale. Can you talk about how you formulate your programming?

MW: It’s always difficult to articulate matters like this, but I think that we always strive to identify work that strikes an emotionally resonant balance between concept and craft. What I mean by that is, for example, there’s a lot of work being produced these days where that balance is tilted disproportionately toward concept. There’s a lot of content-based intellectual art, which I respect and much of which I admire, but I feel that if it’s tilted too far in the direction of concept, it risks becoming merely “clever” art or like a one-liner that will provide a temporary hit of stimulation or pleasure or mind-expansion, if you will, but then very quickly the energy of it sort of dies out. It becomes sort of lifeless just like any sort of joke that you’ve heard several times. On the other hand, work that is disproportionately focused on just the craft behind it always runs the risk of becoming kitsch. So we try to find artists who are producing work that demonstrates on the one hand, if not a fully developed mastery of the craft, whether painting, sculpture, drawing, photography, what-have-you, than at least a clear trajectory towards mastery. They’ve shown a discernible degree of mastery over the craft that they’re working on, while at the same time producing work of sufficient novelty and intellectual rigor that it is of interest. The craft is self-evident, but the concept is still going to be surprising. And again, in my experience it’s that balance that is most likely to produce that type of makes-your-knees-wiggle emotional response that I was talking about earlier when I saw the Francis Bacon retrospective.

LK: I appreciate what you are saying about that balance. Art can arguably be too concept-based, and often when you go too far or too purely in the direction of craft, the work will get repetitive. It becomes a visual trope.

MW: Exactly. I do believe, perhaps somewhat conservatively, in painting, in sculpture, as important genres, and I think that obviously their historical importance is well documented, but I think that we’re far from realizing the potential of painting in contemporary art. To say that painting is dead is almost like saying, well, writing is dead. Painting is a means of expression; it’s a means of human communication, it’s a means of education, it tells stories. I once heard that there were only 13 stories in the history of human civilization. You can pick any short story, novel, poem, movie, and put it into one of thirteen compartments. So if you subscribe to that then there’s no such thing as an original story, it’s all retellings of the same thing, and yet, every time you pick up a great novel or a great short story you can have your experience of life broadened, you can be educated, you can be touched, you can have all of the reactions that artwork is supposed to bestow upon you as the viewer or the reader or the listener of the music, whatever it is. And I still think painting is like that as well. I think that to the extent that the human experience evolves, painting will always evolve, and there’s always going to be something that painters can say. That said, I think the people that say things through painting have to be good painters, just like people who say things in novels have to be good writers. People that compose meaningful music have to be good musicians, and again, that’s part of the balance that we’re trying to strike here.

LK: Another question I have about maintaining balance would be on showing different types of work, or different media in the gallery. Do you have any techniques for curating disparate work so that the material balance of things is right, in the context of an art fair or group show?

MW: I think some measure of confusion is good. I think if someone walks into the gallery at an opening and says, “Oh, this is what I would expect to see at Wolfe,” then I would say we’re probably not doing our jobs as well as we should. While at the same time to be all over the map with no coherency whatsoever is also I think a failure. I can’t say that there’s any recipe that I follow or any given technique. We’ve organized group exhibitions around themes, like the current show is organized on a textile theme. We’ve organized group shows based on genre, based on time period, based on, for lack of a better term, a school; artists that know each other and work together, and react and respond to one another’s works. But ultimately we are guided by an aesthetic sensibility. Does the room feel crazy? Does it feel cacophonous—visually cacophonous, if that’s an appropriate term. Is it too crowded? And if we, working with the artists, decide that it’s not and that it all coheres and there’s sufficient visual harmony we’ll go with it even though there’s probably going to be any number of people that walk in and will be scratching their heads and wondering how people came up with this particular grouping of work in space. But again, I think it still boils down to that same type of aesthetic balance that I’ve been talking about.

LK: I was impressed to see that the work you brought to artMRKT could be seen to appeal to different viewers and collectors. I was curious if there was any direct intention to appeal to particular sensibilities or tastes.

MW: The art fair paradigm is weird in that sense because you’re given this 10 foot by 12 foot set of walls, and you’re surrounded by 50, 60, 100 other galleries doing the same thing. It’s kind of impossible to walk through an art fair and not feel sort of visually assaulted by images, objects, that combine to—produce complete visual confusion. Part of what you do at an art fair is try to give viewers a sampling of the work that you show from different artists. There’s always going to be a challenge. I’ve done fairs, particularly shortly after we opened, where we would go to a hotel room somewhere in Miami or New York and cover most of the square footage of the wall space with something. And it made no visual sense whatsoever. It was lit with hotel room lighting. There was absolutely nothing academic or curatorial about it, it was all purely mercantile, and we did well. And I think really it was kind of after the crash, which coincided with our own evolution and maturing to a certain extent in this business, that we started to realize that you can’t just do that, certainly not in a white wall booth fair environment, and you need to make sure that everything that goes on the walls is somehow complimentary of everything else, while at the same time maximizing the likelihood that someone’s going to like something enough to acquire it. Ultimately, I feel like our job is as agents. We are representing artists and we want to sell the work on their behalf. Obviously we want to sell it for our own purposes, but in my view, if there’s an artist with great potential, or an already great artist, and that artist is not spending time in the studio because they have to have a part-time job or a full-time job to support themselves, that’s an unfortunate situation in the grand scheme of cultural life in our community. If we can mitigate that and enable them top work fewer hours, or maybe give up the job, or take the summer off because they can make some money through art sales, then we feel like we’ve really done our job. For that reason, there’s always going to be an incentive to showcase as much work from different artists as possible in an art fair setting, while at the same time resisting the temptation to take “Here’s all the artists that we work with, let’s throw one piece from each one of them up on the wall,” since that can easliy undermine everybody. So that becomes actually part of the biggest challenge because every single fair you have to say to probably the majority of the artists you work with, “Sorry, we’re not going to bring your work to this one. But we’ll bring it to the next one, or the one after that.”

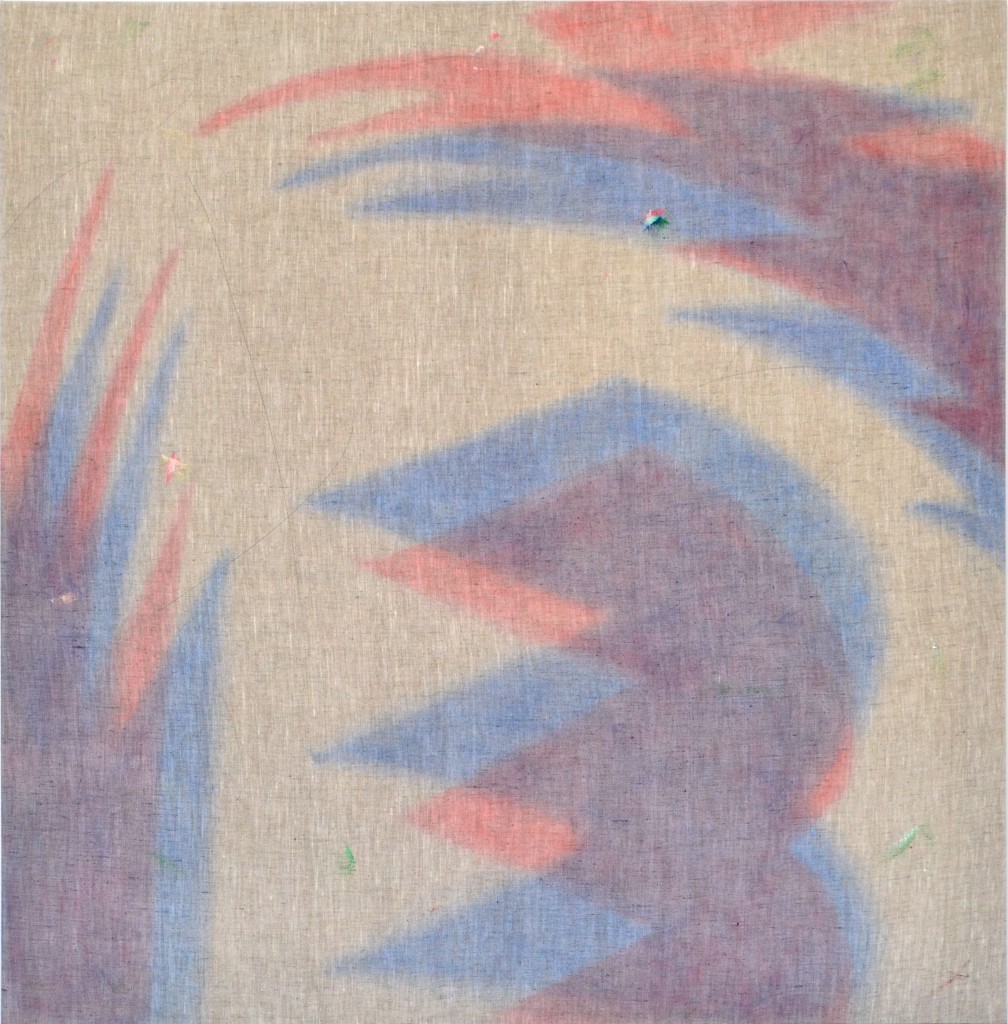

Bryson Gill, Untitled (Textile 4), 2012. Oil on linen. 37 ½ x 38 ½ inches, 2012. Photo credit: Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art

LK: I’d like to talk about your most recent show, Immaterial, which featured artists Michelle Blade, Bryson Gill, Rachel Kaye, Sarah Thibault, and Jacob Tillman working with textiles as media in contemporary painting. What inspired this exploration of textiles?

MW: Let me start by giving credit where credit is due. This show was curated by our Assistant Director, Alexis Mackenzie, who is a wonderful artist in her own right across the Bay Area and beyond. She came up with the idea and she selected the works for the show, in concert with me. We liked the idea of painters, in particular, rendering textiles in paintings as a kind of turning upside down of the generally accepted view which is that a lot of textiles are made, to serve similar purposes as paintings or as decorative art, even though they’re often primarily functional objects. People look at a plain white cotton fabric and think, “that’s like a canvas. I can make something out of it.” So, we all wear art or we have carpets or wallpaper, what-have-you, and so it’s the textile designers emulating in a certain way the historic function of painting. Now we have painters that are sort of taking textiles and incorporating them into their paintings to kind of just reverse that trope so to speak.

Michelle Blade, Untitled, 2012. Acrylic on dura-lar, 92 ½ x 42 inches, 2012. Photo credit: Lucy Kasofsky

LK: Would you say that any of the traditional perceptions of textiles, such as being associated with domestic space or as utilitarian in nature, hold true here?

MW: I think it was a brave choice for Michelle Blade to have produced a wonderful painting on vellum that is now on the floor, where people are invited to walk on it. That’s truly inverting the traditional roles of painting versus carpet textiles. Needless to say, when we had the opening, because you can see there’s no sign that says “please walk on this”, it’s just sitting there, and so of course, during the opening most people took great pains to avoid stepping on it. What’s the purpose of a carpet? It’s for you to walk on, and here’s something that because it looks like a painting everyone was afraid to walk on, so it was kind of funny to look at it that way. But you know, none of the work on display now is actually textile art, it’s basically paintings of textiles. The other thing that I think is really interesting about textiles in general, relative to utilitarian images in contemporary society, is that right now every image we see, not every one, but most of them tend to be pixilated because we see them on screens. Meaning they’re comprised of thousands of tiny colored dots that combine to produce some unified visual impression. Whereas, if you think about textiles, all textiles are made of lines. Thousands and thousands of thin lines of colored thread crisscrossing each other, that’s what a textile is, and yet they are so tightly woven that they similarly cohere into a unified visual whole, but have been doing so for thousands of years.

Michelle Blade, Macrame Window, 2011. Acrylic on dura-lar, wood, hardware. 50 ¼ x 38 ½ inches. Photo credit: Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art

LK: Do you think that common perceptions of textiles are responsible for the categorical separation of painting from other textile arts? I noticed a comment in the show description relating and comparing the application of paint to canvas in painting to the application of paint or ink in practices usually considered textile arts.

MW: We started from the observation that canvas is a textile. When you are applying paint to canvas, it’s really no different from applying ink to fabric to make a print. It’s how the end product it used. In one case the thing is stretched on stretcher bars and hung on a wall, and in other cases it’s either worn as clothing or put on the floor, or used as wallpaper or something else, or a flag or a banner, but I think it’s the same thing deep down what’s going on. It’s taking a woven object and applying color and pigment to it in a way that produces some type of effect. The choice to use it in some domestic or utilitarian fashion as opposed to elevating it, infusing it with some type of sacred virtue so that it belongs on a wall or a pedestal, is a very interesting thing to think about. Again, we get back to Michelle, she’s done this, she’s taken something that normally would bestowed with a sacred—when I say bestowed, I mean it not in the religious sense, but just like, OK, this is an object that is beyond utilitarian—but she’s put it on the floor just to watch how people deal with that. There’s also—and I could riff on this for a long time, the role of money in it these days, and how the choice to take a piece of fabric to which pigment has been applied and characterize it in a certain way gives rise to the potential for enormous amounts of money to change hands, whereas to apply pigment to fabric and do something else entirely with it that’s utilitarian in nature doesn’t. Particularly in other cultures, and I’m thinking of Middle Eastern and Islamic cultures, I think that differential is much less pronounced historically where religious art and domestic art were not divorced so much from one another, and utilitarian art and quote-unquote aesthetic art were not necessarily separated from one another to the same extent that they are now in our society certainly. The way we respond to different objects—function is probably no different than humans have been doing for thousands and thousands of years, it’s just that there’s now this mercenary aspect to it that’s very new, and I think we as a culture, and we as people working in the fine arts community are still trying to get our heads around it.

LK: What would you say is one of the most memorable events or exhibitions that you have organized in this space?

MW: In 2008, we went to China, and again, this was before the crash and during the great boom, both commercially and academically in contemporary Chinese art. We went to China and made a documentary film where we went around and looked at various artists that were practicing. The idea was that we were going to select a small number of them and bring them back for a show here, which we did. So I think the show that we did was probably the most memorable. There you’re dealing with a visual tradition that’s 5,000 years old and we found these practitioners who were not doing big candy-colored faces of little kids wearing Mao suits, which is what everyone was doing back then. What we found were people who had been trained in these ancient visual traditions like calligraphy or landscape painting, and were deploying the same sensibilities in new media. Just to give you one great example, an artist named Wang Tiande had been trained to paint one of the most commonly depicted scenes in Chinese art, which is the mountains of Huangzhou, which is the lake district near Shanghai. You would recognize it because you see it in all sorts of scrolls, it’s been painted by thousands, these little mountains, misty mountains with trees. This artist who had been painting those for decades using calligraphy brushes and ink on silk scrolls suddenly started reproducing them. First, he did it in coal. He got something like ten tons of coal and he trucked them—not into our gallery, but into a gallery in Shanghai, and dumped all these dump trucks of coal, and he shaped them into the exact patterns of the mountainous landscapes that had been depicted in Chinese paintings for 5,000 years. He also recreated the LED board of the Shanghai stock exchange, which showed all of the graphs of the stock price fluctuations going up on a daily basis. It was constantly in motion. You would look at it, and it was identical to what you would see on the Shanghai stock exchange, but you looked at it, and the mountains were exactly the same as the mountains that had been painted for 5,000 years, and we just thought that was brilliant. We brought that guy here, and that sticks in my mind.

Wang Tiande, Gu Shan III (diptych - right), 2009. Digital image, xuan paper, pi paper, stone rubbing. 12.5 x 64 inches. Photo credit: Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art

LK: Is there anything upcoming at Mark Wolfe Contemporary Art that you’d like to mention?

MW: Starting in the fall, we have back-to-back debut solo shows of two painters with enormous potential. Young painters—the first is Sarah Thibault, and after that will be Todd Lanam. That’s really what we love to do the most, is to show everyone else what we think is an exciting young artist who probably has not had a solo show before, but we do think they’re ready for one, and we’re very excited to showcase what they’re producing.

LK: I am looking forward to that. Thank you.

http://www.wolfecontemporary.com/