Vassilios Doupas

Director of the Apartment Gallery, Athens

Interview by: Maria Nicolacopoulou

With the global financial crisis well underway and Greece being the central financial nucleus, I had the chance to speak with one of the main protagonists of the contemporary Greek art world. A graduate of Goldsmiths Curatorial MA, Vassilios Doupas is the Director of ‘The Apartment’: a contemporary art gallery in Athens, Greece and a member of both the Greek Art Galleries Association and the New Art Dealers Alliance in New York, NY.

Mr. Doupas has lectured at Deree College, Athens, The Southampton Institute, UK and Goldsmiths College, London. He was a Visual Art Assessor for the London Arts Board in 1999-2000 and sits on the board of several committees, including the Pedagogical Institute in Athens, which evaluates the quality of art books in higher education. Together, we navigated the recent economic crisis and its effect on Greek contemporary art and cultural life.

What do you think are the main issues that have affected or affect the production and generation of contemporary art in Greece and how do they relate to more global developments? Do you think those issues transcend the locality to an international level or are they more isolated and site-specific?

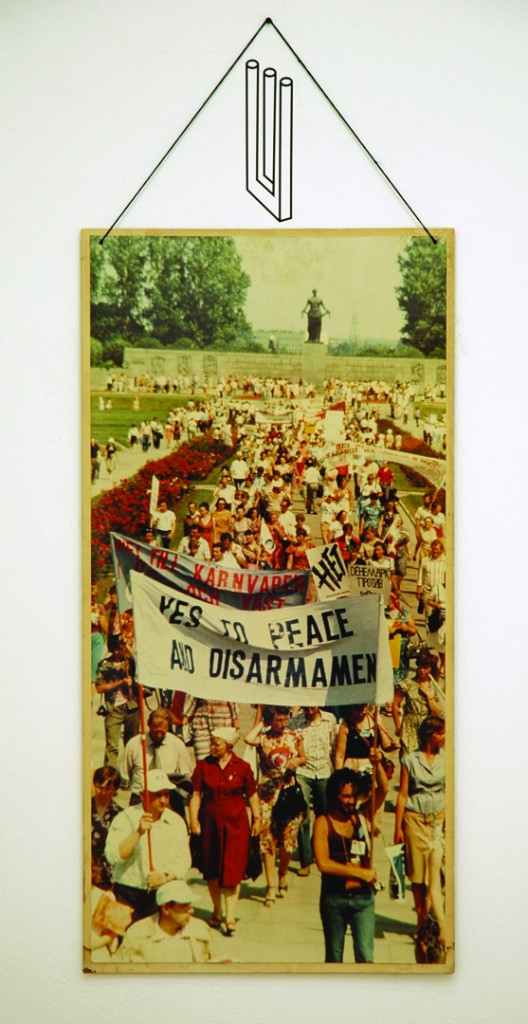

During the last 30-40 years cultural developments in Greece have been following closely the methodologies of the western model, yet we have not been entirely in sync with it. Contemporary Greek art went from being an intersection of politics and ideology in the 70s, largely in response to the dictatorship, to the self-complacent 80s and 90s, when we experienced a climate of postmodern freedom. The 80s and 90s were crudely individualistic and any debate on the role of art was painfully absent. It was also a time when the country entered the EU. A lot of Greeks benefited from the new opportunities, and a new lifestyle was embraced. They started to travel abroad visiting museums and art fairs and they wanted to follow through. But as there was no serious infrastructure to critically appreciate art from other countries, value its differences and seek similarities to our condition, it soon ended up being a question of trend. And, as issues concerning the role of Greek art in a globalized world and the status of contemporary art production were not being addressed, the local scene remained small and inaccessible to a wider audience. Certain private galleries and some visionary collectors were the only ones to assume an educational role and pave the way for an open-ended dialogue with colleagues abroad. Thanks to them, over the last ten years we have been experiencing a strong interest from curators, collectors and museums in contemporary Greek practices. Today, many young Greek artists are exhibiting internationally in biennales, museums and important institutions.

What is interesting for me at this point is that artists are re-visiting the past – essentially what had been produced in the 70s when art was a radical gesture towards the dictatorship – and looking for new tropes to address similar concerns. They also try to connect with other cultures regarding common sociopolitical conflicts that globalization has foregrounded. Hence there are a lot of Arab artists in the current Thessaloniki Biennale, who question the current state of democracy and a lot of European counterparts who tackle postmodernism and the free economy in the 3rd Athens Biennale, aptly called ‘Monodrome”. What I am trying to say is that we no longer consider issues about national identity and “the self” in times of global capitalism as if they were only happening to us. We now seek to share ideas, concerns and artistic collaborations which sometimes extend beyond the boundaries of the art world.

What does it mean to have an art gallery today in Greece under the current sociopolitical conditions, in relation to the recent past of approximately 10 years?

When I left London for Athens in 2001, I was highly optimistic about being part of a new scene in the making. It was a time of general elation as the stock market was doing well, people’s taste was changing, younger people were at the forefront of culture and of course we had won the 2004 Olympics.Things were booming; there were new collectors, international coverage, quick sales and a general enthusiasm about the young Greek art. Of course those were the market’s boom years everywhere: in the West with the rise of Art Basel Miami, hedge funds investing in art and an unprecedented and misrepresented focus on emerging artists.

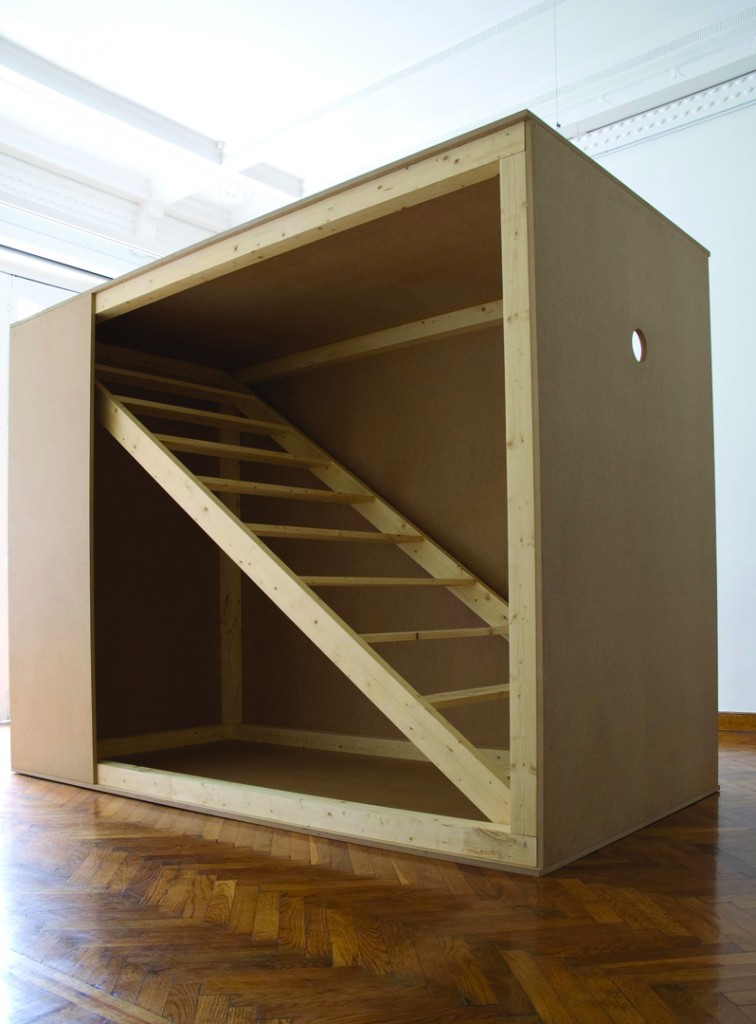

When the global recession hit us, Greece was still in the dark. Politicians had done their best to dissuade any suspicion that there might be an end to our fake prosperity. Consequently, an acute identity crisis followed at all levels: national, personal, political, and geographical. It had to do with Greece’s position in and its relationship to the world. It was particularly unclear among gallerists and curators what to present in uncertain times. Many artists started to redefine the principles behind their work as the market was no longer a viable force. Out of this environment, experimentation began, pushing art and culture in new directions.

For better or worse, the art world has now returned to its ‘exclusive’ nature. My shows for example are geared more towards the art lover who can engage in the familiar art vocabulary, rather than to a wider audience, hungry for images that can potentially re-shape the canon. There is less traffic in the gallery but I am pleased that those who decide to visit the exhibitions are now more knowledgeable and involved. Having said that I miss the ‘epiphany’ that art can have on the uninitiated audience.

How has the crisis affected the art scene in Greece not only commercially, but in terms of cultural initiatives that are trying to tackle and respond to the situation? Do you think the global financial situation will push the Greek art scene to the forefront of the global cultural epicenter, like what happened with China?

There is a return to substance. There are more artist-run initiatives, artists are opening their studios and there are more lectures and public talks being organized. There is a desire and an awareness of art’s more profound role as an examining lens of society. For the first time in Greece, we see a valid re-examination of the past in relation to its influence on today’s society. Feminism is being discovered – in Greece there was never really a major feminist movement or any feminist academic discourse. The formalist approach towards art hasn’t changed, but the context has. Art’s position is being reshaped. There is a new sense of creativity generated by this chaotic situation, which was recently highlighted through ReMap3, a private initiative to map a new cultural geography. Contemporary art was at the heart of this, with galleries showing work in run down spaces and dilapidated buildings in the center of Athens. Greece is often being portrayed as the black sheep of the EU by several media and TV outlets, but this is a motive for us to prove to the world the relevance of Greek art. If you examine the Greek sociopolitical paradigm closely, you can see that why the local is simultaneously global.

What do you think the result of this adjustment would be for the Greek art world – and beyond perhaps if you want?

One thing is for sure: Greeks are uncomfortable with the capitalist system. We are still very keen consumers, but we are not ready to give up our civil liberties for the sake of corporations. This is the reason people feel the need to go out and speak, express themselves, protest, and for the first time, this applies to everyone, not just activists. Now you see the guy next door with his family out in the streets protesting against corrupt politicians who only care about their own interests. The Greek crisis is not economical, it is primarily political and structural: “A corrupt country where everything is done by politicians to murk the waters rather than provide solutions.” There will be major changes, with new political alliances to be formed. It’s a decisive moment for Greece and it is a great time to be here and experience all this change. Every corrupt politician is, for once, scared of the ramifications.

In terms of Greek art, I think it is also a decisive moment in repositioning Greek art globally, making it more visible, because now it is relevant to all of us. I remain optimistic and am looking forward to what the future brings.

What are some major cultural initiatives currently taking place in Greece that you believe will affect the future development of the art scene, whether short or long-term?

The state never had a bigger plan concerning the dissemination of contemporary Greek culture; money was often being plunked into shortsighted initiatives. There have been so many missed opportunities. Recently, the private initiative has been more reliable. I don’t simply mean businesses, who still do not understand why they can play a pivotal role by supporting art. I also refer to the several private foundations who support Greek and international art and culture and have an exceptional program of events. The Stavros Niarhos Foundation, which is currently being built in a huge complex and includes a public library and the new opera house, will most certainly affect the social, cultural and even architectural landscape of the city. It will not only rejuvenate a whole area, but will redefine the way Greek people connect with art and culture daily. It will enrich their lives. The fact that this change will come out of a private initiative demonstrates once again the absence of the public sector in Greek culture and its inability to understand the role it could play. The SNF represents the model of a new philanthropy, which is inclusive, innovative and with a bigger vision for the country and its people.