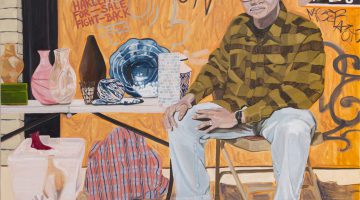

For the past year, Jordan Casteel, Jibade-Khalil Huffman, and EJ Hill have occupied the studios on the third floor of the Studio Museum in Harlem, privy to the flux and flow of traffic on 125th Street and spectators of the events that rally on the plaza in front of the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building. Under the auspices of the Studio Museum’s Artist in Residence program, these young artists are now part of a new community, one that has become a part of their lives and their work.

On the advent of the A.I.R. exhibition Tenses, organized by Amanda Hunt, NYAQ’s Nicole Kaack discusses the installation with each of the residents. The conversation with EJ Hill will be available on NYAQ’s website upon the completion of his series of gallery performances.

Poet and artist, videographer and sculptor, Jibade-Khalil Huffman’s works defy the limitations of traditional media boundaries, bringing a poetic sensibility to visual manipulations. Huffman’s sculptural installations of video, found objects, and prints explore the particularities and possibilities of form, refuting the structures that foreclose on our ability to understand ourselves and each other.

When I first went into the installation, because of the space and because of the ways that things are reflecting and literally interacting with each other, it feels so much like an environment. I was actually a little surprised that there was more than one piece. I noticed that in your past installations, things did feel a little more discrete.

In other shows, it was kind of like the pieces needed that space. And I’ve also just not really known how to put these two things—video that is not on a flat screen and photographs or other sorts of objects—together. That is connected to the frustration of being weirdly boxed into the categories of “you make video and you’re a poet.” These other aspects of my practice are so important to everything else. With regard to Tenses, the inherent claustrophobia of that space worked out with my interest in, on a formal level, executing an exhibition that isn’t fixed. When you’re trying all these different things you have a certain ideal viewer. You are making, kind of, for them.

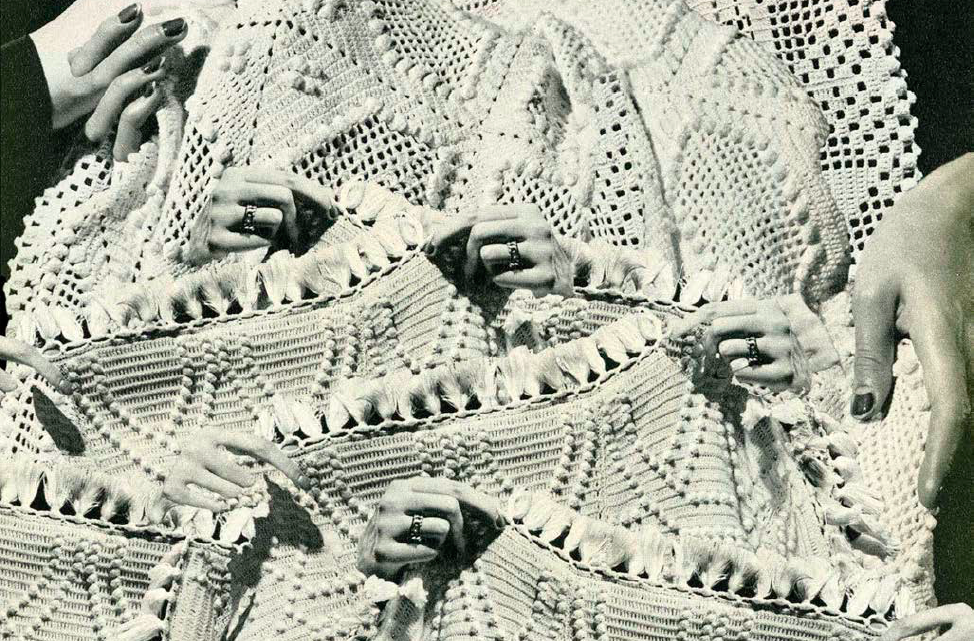

Untitled (Landscape), 2016. Archival inkjet print, 30 × 26.25 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

With each of the media there is such a particular way in which you use it. For example, the way that you use lines is interesting, particularly in this back and forth between the more sculptural objects like the prints hanging out from the wall or the windshields and the prints.

With windshields, I started with this crazy plan to have humidifiers in the space. When I went to the glass shop I was asking about the defrosting lines. And the guys broke it down, basically you solder a metal line into the glass. So I was going to do that. Humidifiers were going to be right under the windshields, to create this steam and then the defroster would turn on. It’s something I still want to do. But I tend to . . . I put everything, time, months into a project, and there are some continuations of things, but then I’ll just get: “That’s it, I figured everything out.” I am really into this continuous exploration, but in terms of what I am showing, it’s kind of a challenge to myself to think about the specifics of the project and what that needs. But that doesn’t mean that if I get some idea with the windshields again, I won’t throw it in.

Between projects, the thing that continues for me is maybe a way of shooting stuff. It’s just the way in which I was trained as a photographer by Stephen Shore, in this super rigorous photographic scene, which still affects how I make video, how I photograph things. So those considerations are always there. If there is any sort of recurring thing, it would be these formal aspects. And this idea of foregrounding, via layering and other factors, complexity. I am depicting the nuance of black women as counter to the idea of the angry black woman. The Studio Museum installation is about a kind of rage, but giving that the true space that it deserves, not the reductive generalization of the angry black woman, but rather this multi-faceted thing.

In your video work for the Studio Museum show, Stanza, there are moments where you use image interchangeably with text. There are things that are signifiers of other things that lead to other ideas.

Let me first say that, across the board, I am resistant to the idea of me ever, in a more general sense, doing one thing. For me, the project is the most important thing. I think that some artists deal with whatever idea they want to deal with, but via their set of tools, their brand of rigor. I am interested in changing. I’ve talked about it with Amanda Hunt, that I wouldn’t say there’s a centerpiece, or cornerstone, of the work. For me, within a project, one thing is not more important than another, including language. And that’s the only reason that I say adamantly that it’s about the particular idea, not the particular form.

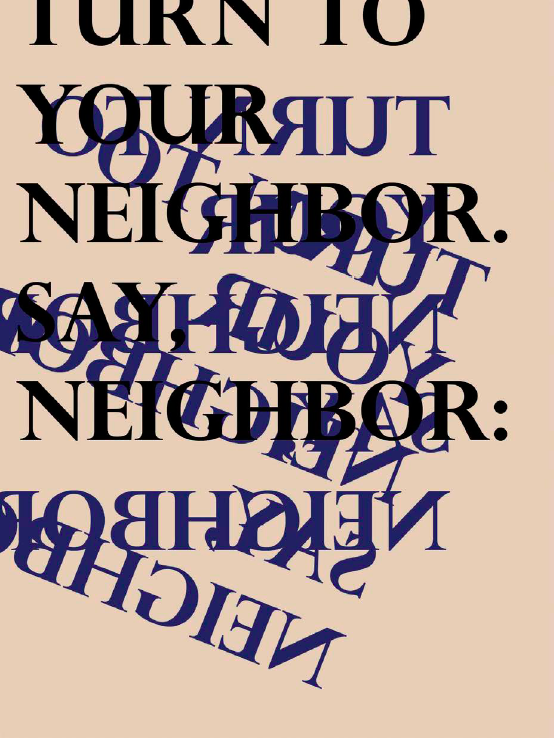

Call and Response, 2016. Silkscreen on linen, 36 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

It is finding the way to realize the medium specificity of the idea, not the object. I definitely feel that you are changing a medium, that you are not exclusively a thinker about language. The multiple identity of your work comes in the layering, the way that you use shadows and transformations. For example, that print that says, “Turn to your neighbor, Say neighbor.” Another thing that struck me about that phrase is that it is so proscriptive; it is a reflection. You are being told what to tell.

I am sort of interested in it as an openness, a possibility. It doesn’t tell you what to say. The text during the video ends with a straight up colon. This isn’t the first time I’ve done that. I’ve ended several poems with a colon. I sort of stole the idea from John Ashbery.

That was a clip of the program that I was interested in. I think there is a part where you say you’re less interested in making a lyrical “narrative-based work” and more a “studio-based video.” What does that mean to you?

What I mean by that is a poetic kind of work.

More abstracted.

That’s why I use poetry. Because I am a poet and that’s natural to me, but also because the logic of poetry actually allows you to do these things that can reflect what’s happening visually, these fragmentary narratives. With most writing, there’s this logic and expectation built into it, except poetry. There’s obviously exceptions, but for the most part it’s sequential. And it’s the same thing with narrative cinema: that A happens, then B happens, then C happens. I think people going into video have a similar expectation. So when you disrupt that with poetry, there is a logic implied that, even if you haven’t read that much poetry, that you can accept more. Other things can then happen.