Planes in space: ruby onyinyechi amanze’s studio

ruby onyinyechi amanze is a contemporary artist working primarily in drawing. I first saw her work at the Studio Museum in Harlem, where her piece that low hanging kind of sun, the one that lingers two feet above your head, (never dying) house plant… (2015) was on view as part of A Constellation. Shortly after she was announced a 2016 Prix Canson Finalist, I heard her speak at The Drawing Center as part of the finalists’ exhibition. The following piece reflects upon our August conversation in the artist’s Queens Museum studio, where we spoke about space, play, and memory.

In one area of ruby onyinyechi amanze’s mural-sized drawings, an elbow from an Egon Schiele drawing might point towards a Bill Murray billboard silhouette or a relaxed sunbather from a spread in a vintage Vogue. The original context of these sources is not so important to the artist as the characters whose bodies they come to form; amanze’s vaguely human cast of alter egos and hybrid identities forms a loose vocabulary threading through all of her recent work.

Initially it was a cast of one: Ada, the alien, born as the artist’s alter ego. Ada’s face might be recognizable as the artist’s own, but her body glows with highlighter-yellow acrylic paint. Ada means “first daughter” in Ibgo, the artist’s father’s tongue—an appropriate title for the artist’s first developed character. But because Ada acted alone, she was easily (and understandably) mistaken for the artist herself rather than a double. Thus, other characters were soon born into the page, including a leopard named Audre and a merman. While not based on specific people, these characters usually draw on some aspect of the artist’s history. The merman, for example, emerged out of the artist’s interest in people of the Rivers State in Nigeria, who identify as people of the water more than of the land.

If the stories of these characters and their origins sound more like the beginning of a theatre piece, or science fiction, it may be because the concept of play is so fundamental to amanze’s studio practice. This is not a concept to be taken lightly: “Play is connected to freedom, and not everybody gets to play,” the artist noted in a recent talk. The interactions of these imagined characters may convey more lucidly how sociopolitical interactions outside the studio affect the artist. For example, amanze considers her own identity to be somewhat hybrid; she was born in Nigeria but raised and educated in the UK and the US. This hybridity is ripe for exploration, as manifested in works that collage materials and narratives. Play for amanze could then be described as a method of redefining one’s experiences, or imagining how the world could otherwise be.

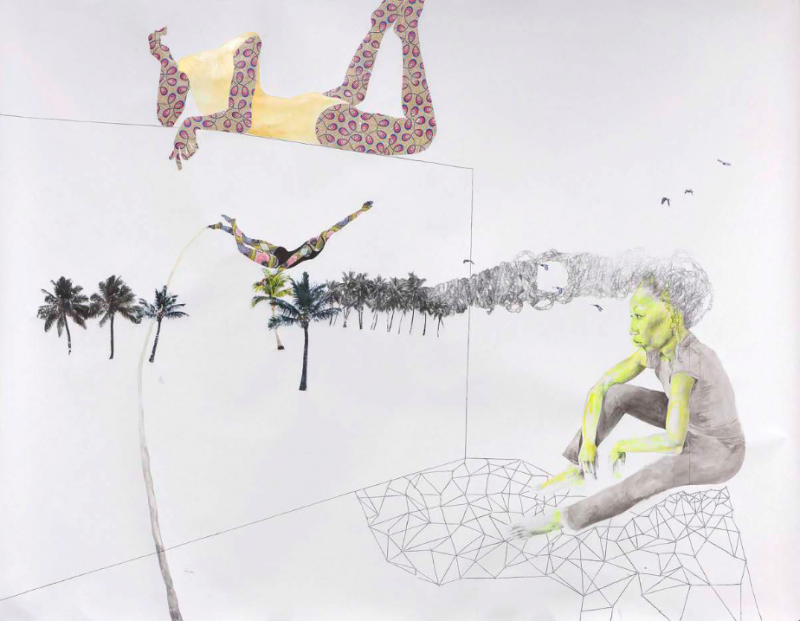

either way, you’ll be in a pool of something, 2015. Graphite, ink, and photo transfers, 40 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

In her studio, the artist also noted that “play” means tapping into a heightened sense of curiosity. She recounts feeling excited by visual challenges such as remembering the color of a woman’s sweater. Though curiosity manifests itself in many forms, such specific moments of intense interest are often suppressed. It is clear from amanze’s works that her heightened sensitivity to details, visual or otherwise, is integral to her practice. Play ties into memory; by remembering interactions or descriptions of events from friends, the artist might piece together a new model or situation for her characters in the studio. Memory is important to viewing these works too; once one realizes that the characters carry over from one drawing to the next, the act of remembering constructs new narratives from the viewer’s perspective. These alternate narratives may be completely unrelated to the artist’s intentions but can be considered just as valid, especially because each drawing is only loosely rendered as a scene. “I feel no obligation,” amanze says, “to give the viewer any more.” Not knowing their original models, the viewer can associate entirely different or imagined people with the depicted cast, just as one might associate a book’s character with a close friend.

For amanze, the most exciting character is also the least defined: space. “Thinking about space,” she says, “is now 60% of it for me.” When in the same room as drawings of this size, one might easily feel overwhelmed. But because of this crucial element of open space in amanze’s work, her drawings feel physically accessible; one can sense the tension between elements on the page and nearly dive into them. A gaze from one character towards another charges the distance between them. The change in scale of the repeated icon of a houseplant or the difference in scale between a body and a swimming pool anchors an invisible vanishing point, giving the white space dimension. Simple gestures towards architecture—a network of lines or simple diagram of the shell of a space—similarly help the viewer imagine that, within that space, expansive infrastructures could be supporting the whole drawing. This is perhaps why she spends so much time preparing the drawing by arranging the elements on the page—of course, she is also highly skilled in rendering bodies, and without their convincing forms, these compositions would be less compelling.

with the galaxy beneath her, she remembered the magic of soaring amidst coconut clouds, 2014. Pencil, ink, and photo transfers, 80 x 114 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Space in these works is then “not absence, not negative,” as the artist stresses. The implication of this statement is that the white space of the page is just as full and materially embodied as the represented characters. In this way, the drawings can be conceived of as sculptural. For past installations and performances, amanze has extended this suggestion by introducing foreign, three-dimensional materials into the space. A freestanding pane of glass may become a new drawing surface that opens up another mode of viewership. Fake grass may carpet the floor or wall. In her studio, amanze is now working with a sheet of paper curved into the corner by occupying this interstitial space, the drawing becomes more dimensional and disorienting.

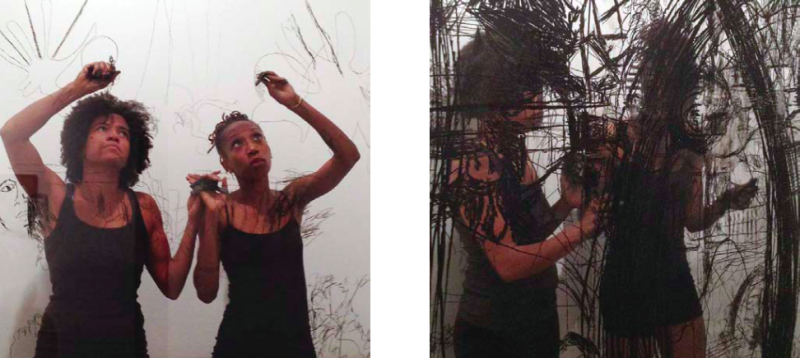

Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze and Wura-Natasha Ogunyi, Twin, 2013. Collaborative performance-drawing, 3 hours, 34 minutes. Courtesy of the artists.

In her invocation of invisible networks, implementation of ahistorical references, and fluid translation of ideas between dimensions, amanze presents a distinctly contemporary approach to drawing, and one that relates easily to the language of the Internet, where a virtual click becomes a physical item at the door and a Roman sculpture might appear alongside a stock photo if one searches online for an image of a body. But while such collapses can often feel impersonal in digital space—amanze notes that play ends when she reaches for her computer—her collapses always relate back to the logic of her alternate world.