For the past year, Jordan Casteel, Jibade-Khalil Huffman, and EJ Hill have occupied the studios on the third floor of the Studio Museum in Harlem, privy to the flux and flow of traffic on 125th Street and spectators of the events that rally on the plaza in front of the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building. Under the auspices of the Studio Museum’s Artist in Residence program, these young artists are now part of a new community, one that has become a part of their lives and their work.

On the advent of the A.I.R. exhibition Tenses, organized by Amanda Hunt, NYAQ’s Nicole Kaack discusses the installation with each of the residents. The conversation with EJ Hill will be available on NYAQ’s website upon the completion of his series of gallery performances.

In monumentally scaled, vibrantly colored canvases, Jordan Casteel captures likenesses of the men in her life—from artist models to cousins, from brothers to friends—with an immediacy and fraternity tempered by a sense of caution. Always black, always male, and always imbued with an ineffable humanity, Casteel’s paintings regard their viewers, engaging us in a way that transcends the objecthood of becoming a painting.

The works in Tenses shift your focus from the interiority of the home to the communal space of the street.

I personally found it interesting that although the settings of the paintings moved from inside to outside—they still had the same intimate and personal depth. There is such individuality in the “things” or people someone chooses to surround themselves with for hours out of the day. I have been very intentional in my desire to preserve the relationship between viewer and sitter. It is beyond important to me that I am a black woman making these paintings of my black male counterparts. It is that connection that has and will always remain the same.

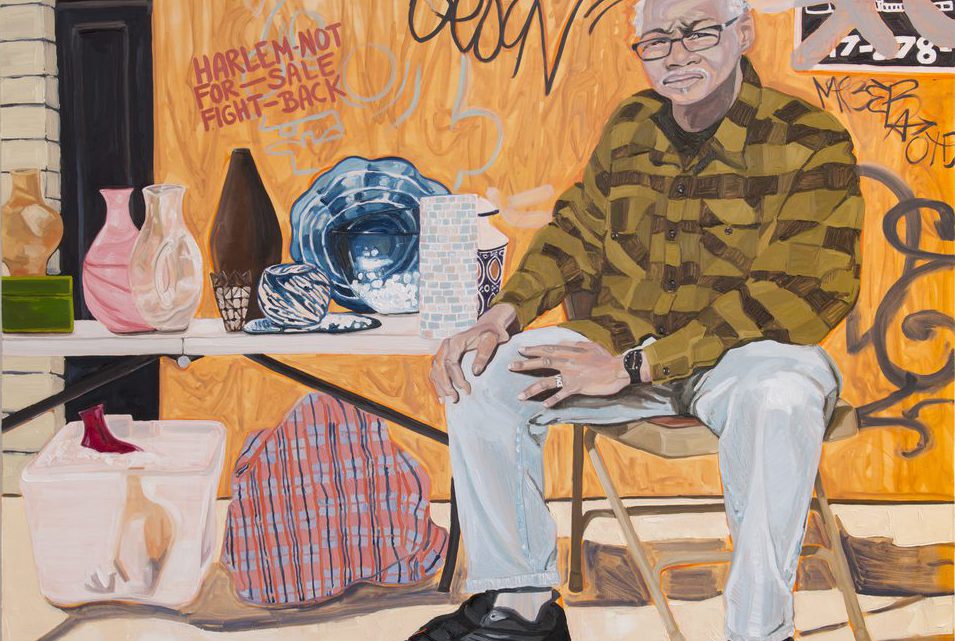

Charles, 2016. Oil on canvas, 78 × 60 inches. Photograph by Adam Reich. Courtesy of the artist.

Your deliberation with color and pattern is evident in the divisions and correspondences made in each canvas. The ties that you draw become the expression of a slower process; we can watch you noticing or deliberately making connections that are variably formal or political.

Slowing people down is absolutely a huge priority for me and my process. I am interested in drawing people’s attention to ordinary everyday moments that they might otherwise be inclined to pass by. In the painting of Stanley, I am painting him in black and white monochrome to specifically draw a relationship between him as a young man and the people represented in the “stop police terror” sign above him. The day that I photographed him, I felt overwhelmed by the casual relationship between him sitting in front of a barbershop and the signs above and beside him. I immediately found myself feeling overcome with emotion; I knew I had to paint him. I wondered if anyone else had walked by and felt similarly. Generally, in the body of work in Tenses there is more explicit language than in previous work. I think much of that is literally just an effect of being on the street—what is amazing is that people are always surprised that the signage represented in my paintings is just as I found it. Nothing is fabricated. I do think that people miss most of their surroundings the majority of the time. Hopefully, through this work, people are able to slow themselves down enough to see things in a way they have not seen them before.

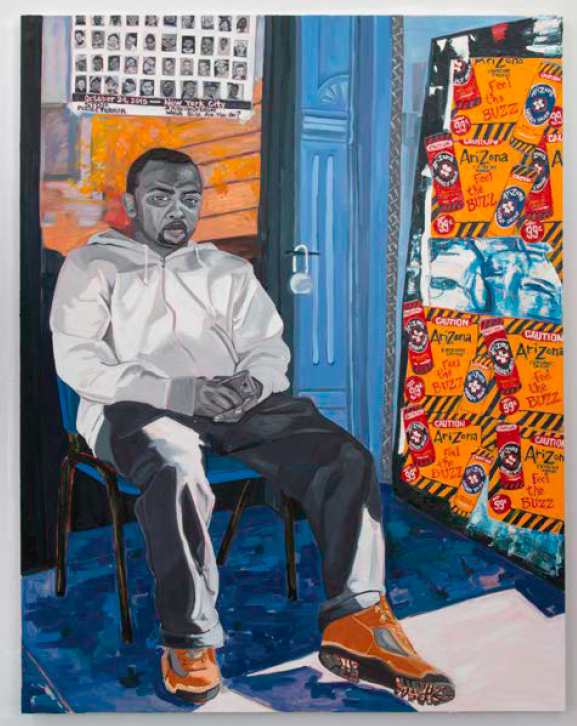

Stanley, 2016. Oil on canvas, 78 × 60 inches. Photograph by Adam Reich. Courtesy of the artist.

In almost all of your compositions that I have seen, you have painted men in seated poses. This adds something to the intimacy and latent familiarity in the work. Can you talk a little about your engagement of your subjects?

I have found that people’s willingness always surprises me. I’m not sure that if someone came up to me and was like, “Hey, my name is Jordan, I’m an artist, could I photograph you for a painting?” I would say yes. Matter of fact, I am pretty sure I would say no. Every person has given me a gift—they have trusted me enough to share themselves with me—a stranger—to become a “painting.” I would say the moment many of them had the opportunity to see the paintings for the first time in person, they were shocked by its monumental quality. As James told me, he expected “a little drawing or something.” What is also beautiful is that I have had the opportunity to really get to know the men of my community—Harlem—through painting. The rapport I have developed is one full of love and support.

I am really interested in this idea that you are introducing of the twinned experience between yourself and your subjects. It’s almost one of synchronous opposition—as a black woman representing black men. Your gaze is sympathetic, but can never wholly be the same, and maybe that is precisely the intimate cautiousness that we have been talking about. Gender is a clear consideration in your work.

I feel that I am, as a black woman, represented in this work. Perhaps it is not evident in a literal sense, but my process, my experience, my lens is ultimately what creates these images. Everything is being translated through my experience. I also think it is worth talking about gender constructions in a similar way to how we think about systematic racism. Projecting onto a body under any circumstance can be limiting—we are defining a body/person before we slow ourselves down enough to truly get to know them. There is generally much more fluidity in the way we function as human beings than we allow ourselves to explore/consider. On a more personal level, I come from a family where there is a strong masculine presence. I have two brothers, my father, only male cousins, three nephews, et cetera. I feel I am in a unique position to share my experience as a sister, friend, family member—I desire to share my vision through a lens of empathy and love.

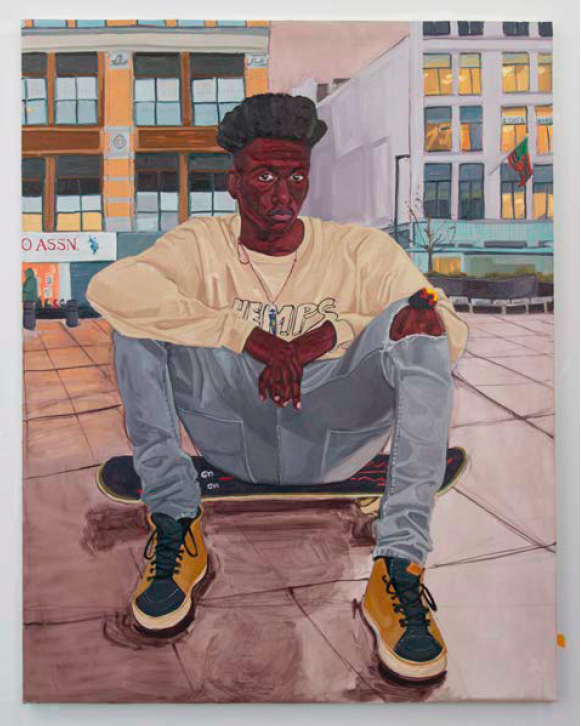

Jared, 2016. Oil on canvas, 72 × 54 inches. Photograph by Adam Reich. Courtesy of the artist.

The power and the gift of your paintings seems to me to be the way that they almost propose an alternate way of being together in space.

As crazy as it sounds, I feel like every time I paint, I give birth and even possibly go to church. It is a personal and spiritual process for me. It gives me life—and in turn, I produce an object that is destined to have a life of its own. I cannot control the lives of my paintings—but I can only hope to set up the best set of circumstances for them to thrive. My hope is that each painting goes into the world and touches the life of another. I hope that the paintings hold a piece of my emotional and physical experience with each subject—allowing them to live a life beyond what you and I can imagine. I have to trust that the paintings’ integrity will allow them to hold space wherever they go and encourage conversation and thoughtfulness that might not have been there otherwise. I won’t always be there to speak on the painting’s behalf—its success lies in its ability to speak for itself.