Visiting your website is like going down some weird interactive worm hole with endless possibilities. I somehow lost track of about 20 minutes stuck in this electronic installation. What the hell is going on?

I have no idea what’s going on either. It’s what kinda does it for me. One of my favorite parts is where you scroll down an animated handwritten/photocopied poem while rubber chickens, cockroaches, cheese-curls, and Brancusi’s Princess X, jump out at you all ending with a pair of dancing red boots and the word DOLLAR.

I originally made it as a supplement to a book and video I made for my recent show U-SAVED-ME. (As an antidote to the despair, and realization, that hardly anyone would see a video, a show, or a book.) But then it grew a life of its own, and became a work in its own right. “Electronic installation” is great way to describe it—it’s a sprawling, shape shifting, out-of-control elongated collage—a poem after having ingested a course of anabolic Mass Builder XXX.

Installation view, U-SAVED-ME at Depart Foundation, Los Angeles, 2016. Photograph by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of the artist and Depart Foundation.

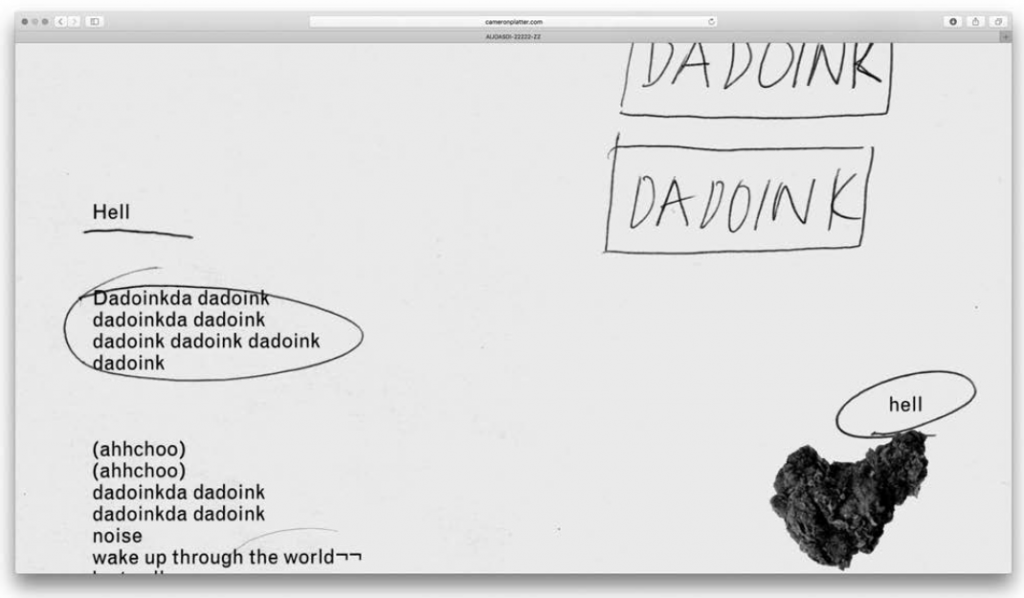

Cameron Platter and Ben Johnson, aoi38-3-aZZZ-4, 2016. Website, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artists.

Using the medium of the Internet appeals to me in that it’s instantly accessible, vast, open 24 hours, (largely) uncensored and democratic, and it’s built on a bedrock of porn. I’m really interested in things falling apart, spilt and split and then making them over again—I’d like to keep on working on this project indefinitely, so that eventually there are all these online ruins and fragments, and dead ends. It’s my contribution to making the Internet a less homogenized space.

Things are hidden, layered, and you need to revisit and spend time with the site. It’s about what’s not immediately apparent, what lurks below.

I loosely based the structure on the 1987 text adventure video game Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards. The idea that you can go on a journey of sorts, you’re questing and inserting yourself into multiple situations, where one thing leads to another, where everything is interlinked. References to R Kelly, Monster Energy, Hooters, crocodiles, The Marikana Massacre, hyenas, washing machines, codeine, oreos, assholes, Matisse, bumper stickers, KFC, Cheetos, and modernism all appear on a single page. That’s kinda central to what I do.

I knew I was onto something when even the coder was really into it. They’re not usually easily excitable. I made the site in collaboration with my friend, Ben Johnson. I couldn’t have done it without his craftsmanship, skill, and eye.

Cameron Platter and Ben Johnson, aoi38-3-aZZZ-4, 2016. Website, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artists.

Do you find the Internet as a platform and medium allows you to engage beyond the physical boundaries of Cape Town when your engaging with the rest of the art world?

For sure . . . The Internet is like water or air. Can’t breathe without it. Can’t breathe in it either. I have compulsions (addictions? therapy?) to work in various other media, but the Internet is a necessary for XXX LIVIN’. The Internet is a life-giving pool, with waterfalls, dolphins, rainbows, and crocodiles and leeches and trash all floating around.

The Internet has made my work more broad in that I’m not necessarily reliant on a particular location to qualify my work. It has made it less easy to be pigeon holed and ghettoized as an African (or Chinese, or US, or Brazilian) artist. Obviously where I live, and what I see happening around me affects my work. But the Internet has not limited the work to more singular narratives (with the associated risks of pastiche and stereotype) and has let it join with other simultaneous stories.

I was at a dinner in LA, after my recent show there, and someone said to me, as a criticism, that my work didn’t look African. I took the criticism as an obtuse compliment.

But, maybe oddly, I do actually think that my work looks “African” and more specifically “South African” despite its pan-Internet use/look/appeal. What is an “African look”? Africa is not a country, and, yes, the Internet does exist here.

My work does comes from a specific place and point in history. From both here and there.

And, interesting that Internet is spelled with a capital “I”, like it’s a country, or person or something?

Alien (Mystim), 2014. Carved jacaranda wood, polish, stain. 50 inches tall. Courtesy of the artist.

How long have you been living and working in Cape Town and how would you describe the art and culture scene there?

I recently moved from Cape Town to Durban, in KwaZulu-Natal, a sub-tropical city on the east coast of Africa. A Johannesburg next to the sea, or a Detroit with palm trees.

Durban, or its isiZulu name, eThekwini (which means bull’s testicles, after the shape of its lagoon) is an example of a relatively successful post-apartheid city. Its storied history (Zulu, Indian, colonial) has mutated it into a rejuvenating, decaying, parasitic 21st century city—a place where the Iron Age intersects with the post-internet. It’s where a lot of South Africa’s talent in arts, dance, sound, architecture is shaped, who then migrate to Joburg, or Cape Town, or abroad.

I’ve always worked from Durban, even when I lived in Cape Town. My studios ran in Durban, and I would commute between the two cities. As an actual physical real-world site, it permeates my work more than any other place I’ve lived. Durban doesn’t have a big contemporary art scene, (that suits me fine, I like to hide out) but it is the heart and home of SA’s craft-art scene, and it doesn’t have hang ups about hierarchies between the two.

I still show mainly in Cape Town, which has a small, but pretty vibrant art and gallery scene. Artists to check out are Igshaan Adams (who works in a scene centred around the Atlantic house studios), Tony Gum, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Bella Knemeyer, Barend de Wet. It has an established network of designers, book makers, sound people, video guys, the advertising and film industries, people who often aspire to a more international scene. But for all its worldly aspirations and postcard values—mountains, clean sea, vineyards—it’s the most violent city in South Africa, and there are places where it feels like Apartheid never left.

If I’m in Durban, I’m on its beach. Which is South Africa’s most inclusive, integrated space. Everyone uses it. It’s got great waves, I love surfing in the middle of this vibrant, fucked, dirty, city. I even like surfing with the trash that is a natural part of a city butting right onto the ocean. It’s not fucking Malibu.

Your use of many different materials and mediums is almost overwhelming, yet it all has such a distinct feeling that it all ties back together. You make ceramics, drawings, paintings, sculpture, weavings, performances, and films. Can you talk about your process and how art and life intersect for you?

Ideally, life would just be art, and vice-versa, and there’d be no need to do anything. Like an endless Duchampian Twilight Zone version of Maurizio Cattelan’s 6th Caribbean Biennale.

I have fantasies of being a painter. I wish I went to one studio everyday. I wish I painted the same thing everyday. But I know this wouldn’t actually work out. I’m too interested in too many different things all at the same time—in replicating and translating a dystopian way of being—where R. Kelly is equal to Manet, A Manet who drinks lean. I have a need to make art as a way of therapy, of self-medicating, as a way to cope with the everyday.

I have a bunch of studios, different ones for woodcarving, drawing, charcoal, painting, collages, ceramics, and video work. My favorite places to work, though, are at my kitchen table (in my underwear), taking sculpture meetings in parking lots, and ordering my head and laying plans for how to micro-manage elaborate schedules while surfing and swimming.

I guess that’s my process. It’s all art . . . it’s just in the translation, and how it’s expelled, vomited, and shat out.

U-SAVED-ME, 2016. Single channel video (color, sound), 21 minutes 7 seconds. Courtesy of the artist.

Some of the materials and process you use, including working with traditional and local craftsmen for your woodcarvings and weavings, have a distinct tie to historical commentary . . . can you talk about this a little and also to what degree art history weighs on you.

Although I’m pretty retiring, I’m interested in engaging with a wide spectrum of society, with a wide range of different people, and finding how everything links up, bounces off each other, and merges.

An example would be my collaboration in making tapestries with the Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre.

The Rorke’s Drift ELC Art and Craft Centre has a great importance in South African art history, although recently its weight, influence, and scope has been largely forgotten. Established in 1962, the Art Centre became famous for its print, weaving, and ceramic studios, in an era when apartheid policies denied a formal education to black artists and crafters. Rorke’s Drift established a Fine Art School that produced some of southern Africa’s most renowned artists and printmakers.

The Centre is also, crazily, situated slap-bang in the middle of the historical battlefields of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, where the famous Battle of Isandlwana, and the Battle of Rorke’s Drift took place. The British suffered their largest ever military defeat against an indigenous force at the Battle of Isandlwana, while at the Battle of Rorkes Drift, 150 British held off an assault of 4000 Zulus.

So, it’s a very spooky and eerie place to be. A beautiful landscape with all these very violent and turbulent memories (literally) buried just below the surface. (And takes a day’s drive to get there, on the back roads, from Durban, so it’s not a very visited and accessible place.)

I’d always wanted to do a project with the Centre, as one of my art heroes, and major influences (my spiritual artist doppelganger) John Muafangejo, a Namibian artist who specialized in super narrative, hyper-personal linocuts, trained there, and many of his works talk directly to the place. So I made an appointment, hoping to find one of the old linocut presses he may have used, which I was hoping (planning) to use to print a suite of my own linocuts.

I didn’t find the press, but I did visit the weaving studio (in an old church whose distinct form had cropped up many times in Muafangeo’s works) and was blown away by these beautiful tapestries (often with geometric patterns derived from traditional Zulu design, or narrative works that carried down oral stories passed down over generations).

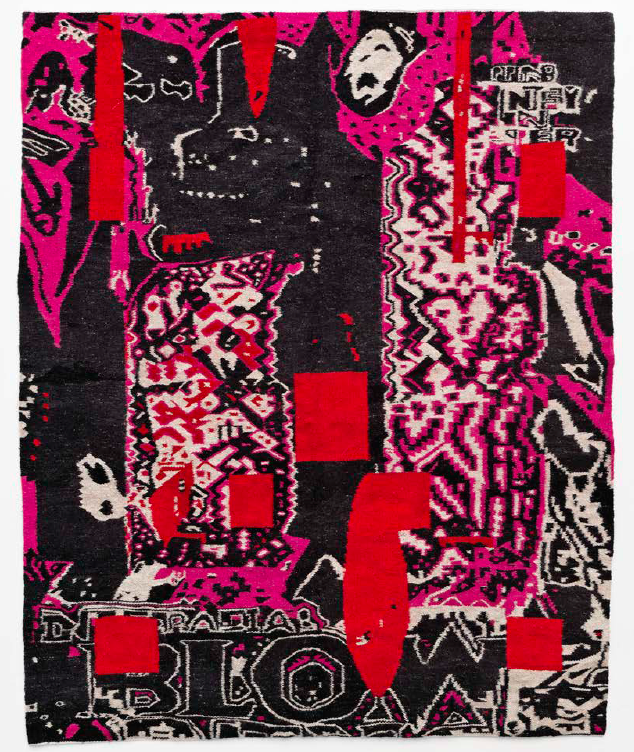

So, this chance encounter, led to an ongoing collaboration/project where we made large-scale tapestries based on my designs of highly degraded and digitally manipulated interracial pornographic DVD covers. These process-driven works are concerned with therapy and the collage of archive, landscape, and history. The conundrum is that these works, based partly on interracial porn are made by observant Christian, highly-skilled rural Zulu women. They’re handmade in the extreme. Raw Karakul wool is hand-carded, hand spun, hand dyed, hand-woven, and hand-stretched on site. Each work takes three weavers six months to complete.

So, it’s a weird mix of the spiritual, historical, conceptual, and personal that enabled, and sustains, this collaboration.

So, yes, art history weighs on me pretty heavy . . .

What’s up with all the KFC fried chicken and Monster energy drinks that show up in your work?

I’m fascinated by consumption, excess, detritus; by unorthodox and transient sources–I’ve had past obsessions with crocodiles and Oreos, R. Kelly and Gianni Versace. And it takes a lot of chicken and Monsters to make a good work of art.

Your recent show at the Depart Foundation was your first American solo exhibition . . . can you talk a little bit about the show?

Even though it was my first US solo exhibition, it didn’t feel like it, as I showed at Depart, an Italian foundation. This kinda made sense as I’m half-Italian–this half-Italian, showing in this half-Italian space.

I’ve shown in the US before, in group shows, in MoMA, et cetera, so it’s not unfamiliar territory. I always enjoy travelling to the US; it’s the high altar for consumption and excess and it’s apparent from my work that I’m pretty into this.

The show was a collage of different elements that I’d been working on for a while.

It was centered around a video (vimeo.com/172642549, password: r_kelly), and the tapestries, which I’ve spoken about above. Instead of showing the tapestries as wall pieces, which I’ve done in the past, I decided to have them on the floor as new-age-psycho-meditation mats, which made sense as the video had a lot to do with Deepak Chopra. I may, or may not have, coated the tapestries with liquid LSD, so that the viewer got an extra kick.

Blow, 2014. Handspun karakul wool, metal complex dyes, and LSD, 250 x 200 centimeters. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Éric Hussenot, and Depart Foundation.

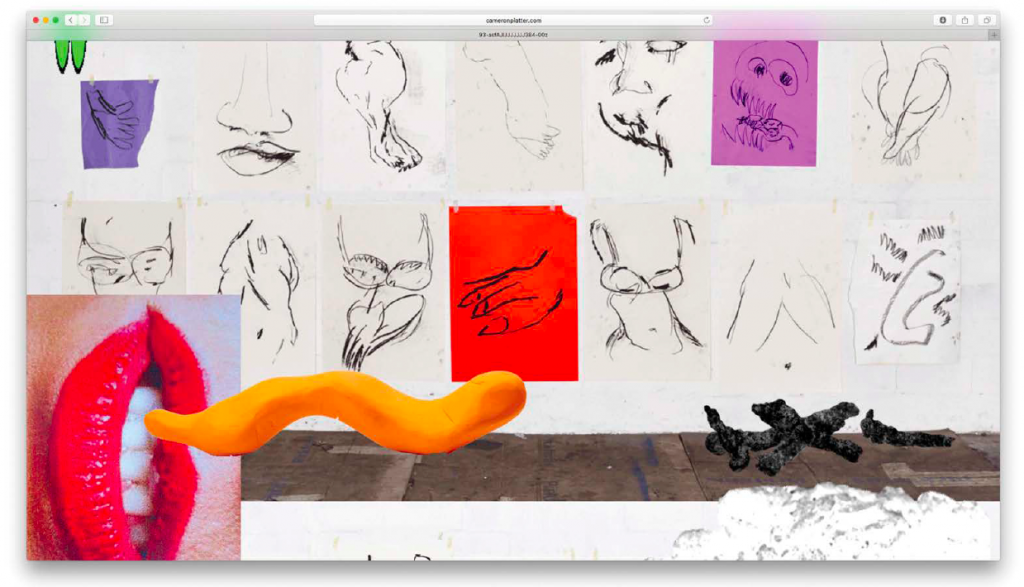

There was also a series of charcoal drawings, life studies of a sex worker named Lamina, made while under the influence of psilocybin. I also showed a suite of large-scale pencil drawings- sort of immense notes that related to the video and the tapestries—I call them landscape pictures.

Sculptures included a carved wooden lounger, a giant carved Oreo, and a UV silicon Brancusi/dick/Cheetos sculpture on a polystyrene base.

Makes no sense, right?

Chaos, Panic, Fear—my work is done . . .

What do you have going on next? You recently had a solo booth at the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London with your Paris gallery. In April of next year you’ll be showing at Ever Gold [Projects] in San Francisco. Should we except chaos, panic, and fear?

Right now, I’m engaged in producing my largest ever sculpture –building a house-studio. It’s a real mind-bender, but in a very good way.

In tandem to this, I’ve been working on a long-term outdoor sculpture project with Éric Hussenot, my Paris gallery.

Closer to home, I’m starting a residency/publishing thing/website/gallery, to bring people to Durban, to have shows in interesting places, et cetera. I had a gallery (Galerie Puta) when I was just out of art school, and want to rekindle this experimental, collaborative, experience of community.

So, in San Francisco you can definitely expect more chaos, panic, fear, or as another bumper sticker reads: I’m going to go Nuckin’ Futs.