Why did you come to New York? Where are you originally from?

I got a Fulbright scholarship to continue my postgraduate work at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia for the 1961/62 academic year. From there, I often took the bus to New York, and, as I had done during a prior year in Paris, I went to see exhibitions, made connections with other artists, and took in the vibes. After that year in Philly, I moved to New York to do more of the same, keeping myself afloat by teaching German.

Regarding the second part of your question: I was born in Cologne, Germany. When I was six years old, bombs fell in the street where we lived. I remember walking by a still smoking ruin on my way to school. We then moved to a small town south of Cologne. And that’s where I grew up.

It sounds traumatic, experiencing that as a child. It seems that the events of WWII may have influenced your work in some ways, such as your 1967 show at MIT, or the work Sanitation you created for the Whitney Biennial in 2000. Would you please talk about this?

War is traumatic for everybody, no matter where.

I don’t think the MIT show made anybody—including myself— think of traumatic experiences. In fact, it was a rather cheerful show, as was its reconstruction at MIT’s List Visual Arts Center in 2011. There are, however, a number of my works, which were “inspired” by the ugly history of the country where I was born and where I grew up.

A significant one is DER BEVÖLKERUNG (To the Population), a permanent installation at the Berlin Reichstag (German Parliament building) that was inaugurated in 2000. It cannot be understood without knowledge of the Nazis’ racist and deadly interpretation of “das Volk” (the people).

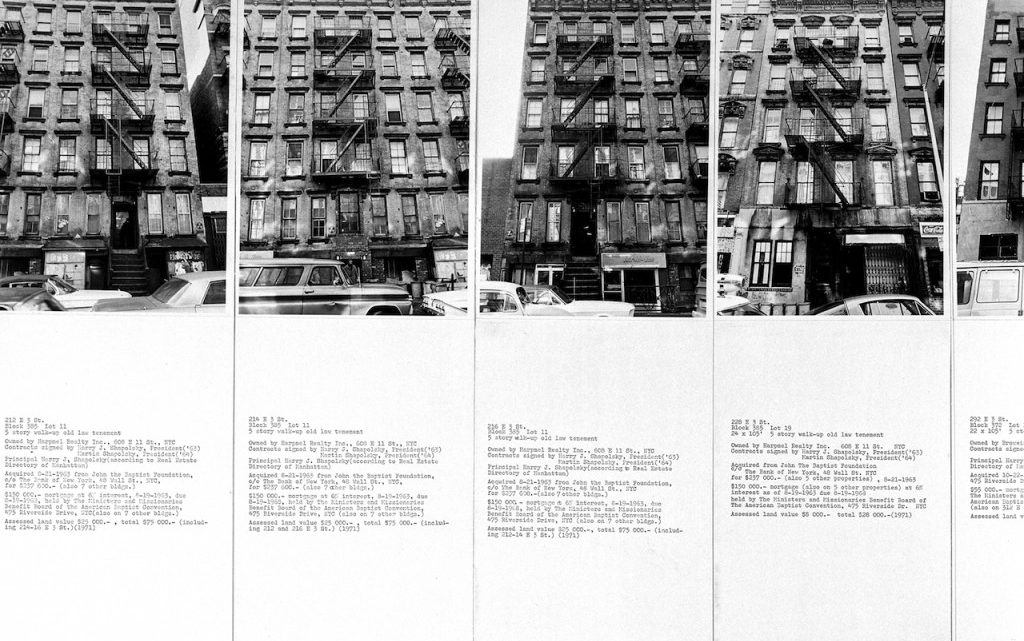

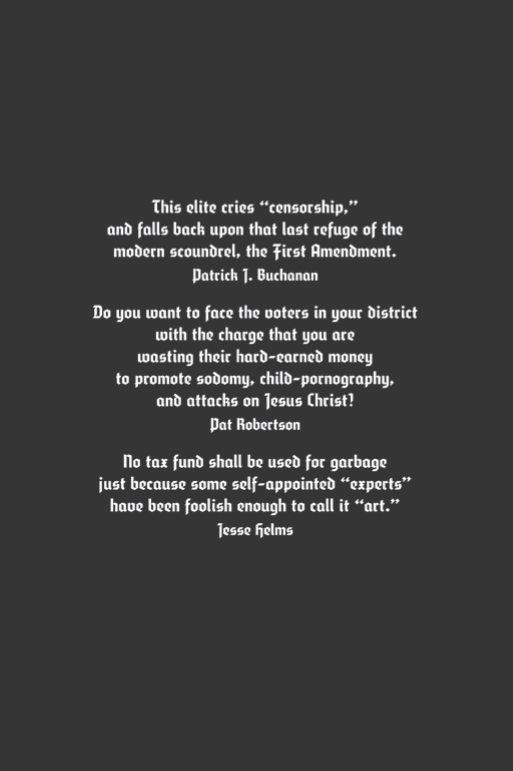

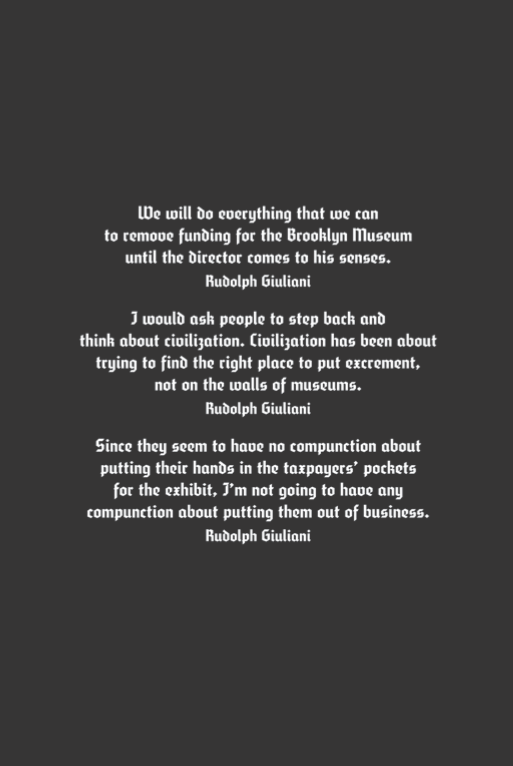

You mentioned my Sanitation piece in the 2000 Whitney Biennial. You are right. Connoisseurs of typefaces could recognize my hint to parallels between the Nazis’ expurgation of what they called “degenerate art” and the “cleansing” of the National Endowment for the Arts by Senator Jesse Helms’s “decency” clause, and to Rudolph Giuliani, the mayor of New York, threatening the Brooklyn Museum over a painting in the Sensation exhibition the mayor wanted to have censored.

Sanitation, 2000 (detail). © Hans Haacke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Collection of Gilbert and Lila Silverman.

Sanitation, 2000 (detail). © Hans Haacke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Collection of Gilbert and Lila Silverman.

Can you talk about your involvement in the ZERO group? How did it shape your later work?

In the late 1950s—I was still an art student in Kassel—I saw a group show of ZERO artists in Bonn. It was my first encounter with ideas and practices that differed fundamentally from the Tachism and art informel I had become familiar with during my hitchhiking visits to Paris, which, at the time, was considered to be the art capital of Europe. I then met Otto Piene in Düsseldorf. I was very taken by what I saw in his studio—and we got along very well. Soon after, l also met his ZERO buddies in Düsseldorf. By the time I graduated in 1960, these encounters had left a trace in my paintings and constructions, to the extent that I was invited to participate in a number of exhibitions by the international ZERO/Nul/Gutai et al. artists network. Two of these exhibitions were held at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. I also connected with artists of the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, as well as with Soto and Takis in Paris. At the 1965 ZERO exhibition in Amsterdam, I met George Rickey who—like Otto Piene—helped me to get my feet on the ground in New York.

What trace did the encounters with Otto Piene and his ZERO buddies in Dusseldorf leave in your paintings and constructions?

Piene was born in 1928. As a teenager he was drafted and assigned to an anti-aircraft battery. Günther Uecker and Heinz Mack were only a few years younger. They all felt an urge to disassociate themselves from the art and the attitudes of the post-war generation that preceded them. They spoke of a new beginning, and they shared a surprising degree of optimism for the future.

Light, and how it throws shadows and causes reflections, played a major role in their works. These were physical phenomena that I then also began to play with. In 1962, water, with its particular physical behavior and properties, was added to my repertoire.

Blue Sail, 1964-65. Chiffon, oscillating fan, fishing weights and thread, dimensions variable. © Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Hans Haacke. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

This brings to mind your Rhinewater Purification Plant from 1972 that was installed at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld, Germany. I appreciate the way in which you created a greywater reclamation project in a museum setting. It seems it was well ahead of its time.

Water, of course, is not always shiny. It is affected by its physical environment, which, in turn, is often shaped by its social environment. The interaction of both was an essential aspect of Rhinewater Purification Plant.

Rhinewater Purification Plant, 1972-2013. Archival inkjet print, 20 x 30 inches. Solo exhibition at the Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, 1972. © Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Hans Haacke. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Let me explain: Museum Haus Lange, like its parent, the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum in Krefeld, is a municipal institution. The director of both is a civil servant, appointed by the City. His budget is essentially the local taxpayers’ money; its size is determined by the elected members of the City Council.

In 1972, the City of Krefeld poured about 11 billion gallons of untreated wastewater into the Rhine. As part of a large triptych in my installation, I listed all contributors to this mess, including the number of gallons of their respective contribution. The largest polluter was a factory situated right on the Rhine that was part of the giant Bayer group of corporations.

Paul Wember, the director of the two museums of Krefeld, was well known, both nationally and internationally as a supporter of “avant-garde” art (that was the word then used for so-called “cutting edge”). Not once did he hint that what I was planning might not meet his criteria for what’s fit to exhibit in his museum. In fact, his office connected me with experts in city agencies from whom I got technical help and statistical information on the city’s wastewater disposal. In passing, it might be interesting to know that Museum Haus Lange used to be a villa built by Mies van der Rohe for a local industrialist.

I’m also interested to hear more about how George Rickey—and Otto Piene—helped you get going in New York.

Thanks to Otto Piene, I was invited to participate in ZERO-related group shows in Germany and abroad. He introduced me to two established galleries, the Alfred Schmela Gallery in Düsseldorf and New York’s Howard Wise Gallery where, respectively, I had my gallery debut in Germany and an exhibition in the US a year later, in 1966.

George Rickey came to my New York exhibition. He wrote recommendations that helped me a lot, and we exchanged works. For a while, my Large Wave (1965) was hanging on his porch in upstate New York, where he had his studio and lived. He later donated it to the Neuberger Museum in Purchase, New York. I still have his piece at home.

What prompted your transition from working with “real time” systems and processes—works like Condensation Cube (1963-65) and Condensation Wall (1963-66)—to focusing on institutional critique, art and politics, and demystifying relations between art and the outside world?

Water, enclosed in geometric containers of clear acrylic plastic, evaporates and condenses on their inside walls. It responds to changes in temperature, caused by air drafts, lighting and other external factors. This process occurs even when there is no viewer to provide an interpretation and give it a “meaning.” Whether one looks at the Condensation Cube as an artwork—there is no definition for art other than one based on a social agreement—or one doesn’t, in either case, the object’s physical interaction with its environment is an integral part of it. In other words: it is not an autonomous object. Its surroundings belong to this “system” of interdependent relations. Very differently, when paintings and sculptures react to their environment it is usually a cause for panic. A conservator is called to repair the damage, and provisions for the control of temperature, humidity, lighting, and pressure have to be installed or beefed up.

Condensation Wall, 1963-66. Acrylic plastic, distilled water, 70 x 70 x 16 inches. Edition 1 of 3: Collection Jill and Peter Kraus; Edition 2 of 3: Collection National Gallery, Washinton, D.C.; Edition 3 of 3: Collection Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany. © Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Lee Ewing. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

It was Jack Burnham who introduced me to systems theory sometime in the second half of the 1960s. I thought its terminology and concepts were applicable to what I was tinkering with. Reading Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s General System Theory gave me a deeper understanding and inspired me to continue with my kinetic, process-oriented works, and also to expand into biological and—toward the late 1960s—to deal with social “systems.”

It was the time of the cultural revolution that shook Paris and other European cities. In the US, the assassination of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. prompted me to write a preface to a lecture that I was scheduled to give. The Vietnam War affected a great number of American families directly. It fired demonstrations on campuses and in the streets of major cities. There were the My Lai and the Kent State massacres. Racial discrimination triggered large public protests. In New York, artists got together and formed what they called the Art Workers’ Coalition to challenge the boards of trustees of museums whom they saw as representative of the forces they viewed as allied with the powers they despised. Nobody had the time to worry about the fortunes of the art market.

That’s an interesting statement. It seems with all that’s going on in the world right now, that it’s similar to the late 1960s. How do you think this time has enabled people to worry about the fortunes of the art market?

It was a very different world. Young artists were not faced with huge debt. They could live in downtown Manhattan. When I arrived in New York, I paid $60 for my one-room apartment on East 6th Street at 2nd Avenue. I used a drill press in a machine shop in Soho to drill holes in acrylic plastic sheets for my rain boxes. Soho wasn’t boutiqueville. It was a neighborhood of blue-collar workers and artists, and it had some grungy bars. In the ’60s and ’70s most of the collectors of works by artist activists were not driven to make a fortune, nor were they motivated to surround themselves with bestsellers for social prestige. Investors who buy and flip artworks were yet unknown. And there were no art fairs. All that changed in the 1980s, during the Reagan years, with a little respite when the Wall Street crash of 1987 hit the art market in the early 1990s.

But, in spite of the art market’s introduction of money as a powerful guiding principle, today there are also artists and activist artist collectives in the US and other parts of the world who respond critically to their social and political environment, and also challenge art institutions. Some do so even in commercial galleries and, occasionally, in major museums. While self-censorship by institutions—and artists—is a common phenomenon, it is not universal. Although critical works rarely make it into art fairs, they are often represented in biennials. In that context, such works usually address issues in the country where the artists are coming from, rather than troubles they see in the host county. The embrace of an international biennial can serve as a protective shield in the artist’s home country.

Is that embrace you describe due to the fact that the positive attention the artist and his/her work receives can make it difficult for an artist’s home country to censor them or their work?

Having been embraced by a prestigious, international venue yields cultural capital to an artist. Her/his work can no longer be dismissed as nothing but political propaganda that crosses the line of what’s acceptable. It is now surrounded by the halo of art. Censoring it risks it to be noted around the world.

Would you talk about your MoMA Poll (1970)? It seems that museums today are invested in a model for systems art that recalls this 1970 work.

I’m not sure about that. Few institutions readily present a work that makes critical references to donors or members of their boards.

![MoMA Poll, 1970. 2 transparent ballot boxes with automatic counters, and color–coded ballots. © Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/tumblr_m162zr5Ui81rntkg5o1_1280-636x800.jpg)

MoMA Poll, 1970. 2 transparent ballot boxes with automatic counters, and color–coded ballots. © Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

World Poll, 2015. Venice Biennale, Central Pavilion, 2015. Visitors responding to 20 demographic and opinion questions on iPads. Tabulation of answers to question no. 8 at the end of the Biennale’s opening week. © Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Hans Haacke. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

I agree that many or most institutions are reticent to present work that critiques its donors or board members. But some artists—Martha Rosler, Andrea Fraser, and Fred Wilson, among others—have created works that are related forms of institutional critique. It seems that your work provided a foundation for these artists and others.

At the time of the 1970 Information show at the Museum of Modern Art, Nelson Rockefeller, the incumbent Governor of New York State, was on the board of MoMA. His brother David was the chairman (also chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank), and their sister-in-law, Mrs. John D. Rockefeller III, was also a board member. I expected the museum would not particularly care for the question of my MoMA Poll, therefore I didn’t reveal its wording in advance. I brought the panel with the question to the museum only the night before the opening. And, sure enough, the next morning, an emissary of David Rockefeller appeared and told John Hightower, the museum director, to take it down. Hightower, to his credit, didn’t comply. Decades later, I found David Rockefeller quoting the question of my MoMA Poll in his autobiography and saying that to keep it in the show was one of several things that prompted him to sack Hightower soon thereafter.

This seems an example of hindsight being 20-20!

Since donors to MoMA and comparable institutions get a tax deduction for their contributions, in effect, taxpayers substantially support these private institutions. I am not a constitutional expert and cannot say whether this obliges the recipients of such unacknowledged public funding to strictly observe the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech (art). The ruling by a federal judge against Rudolph Giuliani over his attempt to have a painting by Chris Ofili removed from an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, which I mentioned earlier, seems to indicate as much. The judge explicitly referred to the First Amendment.

You phrased your question in terms of “systems art” and related it to my MoMA Poll. Whether we are looking at so-called systems or a painting does not matter when we are discussing the acceptance, rejection, or outright censorship of artworks. To prohibit asking the visitors of an exhibition called Information a topical question gives that title a peculiar twist.

Last year, in Okwui Enwezor’s central pavilion of the Venice Biennale, I conducted, via iPads, a poll with 20 multiple-choice questions. 21,000 visitors participated. To the question “Do you live in a country in which authorities censor the works of artists?” 41 percent of visitors who came from “North America” (US and Canada) clicked “Occasional censorship” as their answer.

I’m sorry I missed last year’s Venice Biennale; I would have really liked to experience that work. As for the US and Canadian visitors who responded to your poll, it seems that some must be aware of the highly publicized censorship of artists who received NEA grants during the 1980s, which directly led to the 1989 amendment to the law that created the National Endowment for the Arts, enabled forms of censorship, and eliminated significant government funding from the NEA’s budget.

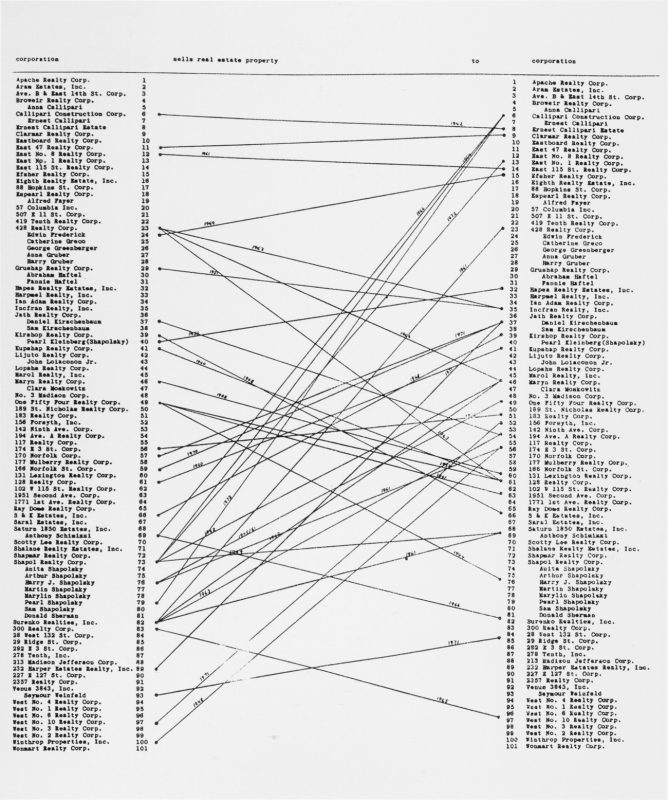

But this shift seems particularly remarkable with your installation Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971. Although censored by the Guggenheim Museum in 1971, that work was also prescient relative to gentrification today. Did you feel vindicated after the work was jointly acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Barcelona?

In 1971, gentrification was not an issue. New York was a rundown city. The properties of Harry Shapolsky and his family and associates were mostly located in Harlem and on the Lower East Side, making them the largest slumlords of Manhattan. Poor tenants were subjected to the group’s notorious rent gouging, and their buildings were known for many violations of the building code. The properties were frequently sold and mortgages were exchanged within the group for the purpose of getting tax advantages and disguising who owned them.

Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, 1971. Two maps (photo enlagements), each 24 x 20 inches; 142 photos and 142 typewritten sheets, each 10 x 8 inches; 6 charts, each 24 x 20 inches; one explanatory panel, 24 x 20 iinches. © Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Edition 1 of 2: Collection of Centre Pompidou, Paris. Edition 2 of 2: Jointly owned by MACBA, Barcelona and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

It took 15 years until New Yorkers could finally see Shapolsky et al., and get a sense of what the fuss at the Guggenheim was all about. It was part of my 1986 exhibition at the New Museum. Already in the early 1970s and 1980s it had been widely exhibited in Europe. The joint acquisition you are referring to occurred in 2007. For many, the inclusion of the work in the opening show of the new Whitney Museum last year was their first opportunity to catch up with what had become a legend. I heard this from people who had lived in some of these buildings. Also the gentrification of these neighborhoods became a topic of discussion.

Your fourth plinth project, Gift Horse (2015), seems to have had remarkably positive responses from most people. I wonder if most understand the intentions of the work, which are revealed by its title, but not by its form. Can you talk about this?

It does seem to be quite popular. Most if not all people who see this skeletal occupant of the fourth plinth on Trafalgar Square do not interpret it as a celebration of the London Stock Exchange and its effect on the global economy, particularly when seen in comparison to the imposing equestrian statue of George IV on the opposite side of the Square. The doctrine that an unfettered pursuit of economic self-interest, guided by the “invisible hand of the market,” will ultimately promote the public good, is followed only by the Koch brothers and their like. The faithful do not normally congregate in Trafalgar Square.

Do you know how most people do interpret the skeletal horse?

The ticker of the London Stock exchange, of course, makes them think of what it represents. Some relate it to paintings by George Stubbs. Judging by what I read and what people say when they speak with me about the Gift Horse, they take it as a sarcastic comment on the capitalist gospel.

I was tickled to see, the other day, that a photo of the Gift Horse was chosen by the editors of the Süddeutsche Zeitung (a national German newspaper) to accompany an article about the planned merger of the London Stock Exchange and the Deutsche Börse in Frankfurt.

Since you taught in an art school for a long time, what do you think is the most important piece of advice you’d give an emerging artist?

Making money should not drive what kind of art you produce. You must find a way to be independent of the fortunes of the market and the predilections of collectors. I know that’s not easy.

With more platforms for selling art today (the Internet in particular) new markets seem to be emerging for younger artists, which is not necessarily helpful for their independence in this way.

Your 1965 manifesto, which calls for the artist to “make something which the ‘spectator’ handles, with which he plays and thus animates…” seems to have a relationship to your current work. Although the form of your work has changed, has the concept remained relatively consistent?

I believe the viewer and the works—not only mine—interact in an untraceable way. Artworks affect people’s attitudes and thereby a society’s consensus—with social and political consequences. That’s what animates the censors. Years ago, I spoke of “Museums, Managers of Consciousness.”1

Your vision as an artist over time has encompassed a breadth of critical issues that concern the future of the world. As an artist, what do you feel is the most important issue to be addressed in this contentious period of history?

That’s a big question. Let me answer by quoting the battle cry of the French Revolution: “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.” Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood—or the non-gendered: Solidarity.