Crossroads Film Festival 2016

San Francisco Cinematheque

April 1 – 3, 2016

Sensory overload is part of the bargain at Crossroads. I went to bed after the last day of San Francisco Cinematheque’s festival of experimental film and video feeling jangled, body chasing its own ghost, but woke the next morning grateful to have encountered a handful of stellar works. Curator Steve Polta’s loaded shorts programs spin out distinct formal and thematic strands, such that The Devastated Land could have served as a title for any number of the films that showed on Saturday afternoon. It was, in fact, a 35mm landscape piece from France—one of several Crossroads works from abroad. Canada was especially well represented, with notable titles by Stephen Broomer, Jean-Paul Kelly, and Daïchi Saïto, but there was also work from Taiwan, Hungary, France, and Thailand. The Thai film, Mont Tesprateep’s Endless, Nameless (2014), made for an especially nice bookend with a later showing of Michael Wallin’s Decodings (1988). The San Francisco filmmaker passed away earlier this year, and if this charged montage of found footage from the 1940s and 1950s is any indication, his work is ripe for revival.

Michael Wallin, Decodings, 1988. 16mm, 15 minutes.

Decodings was one of several excellent collage works at Crossroads. Mike Stoltz’s Half Human, Half Vapor (2015) sets itself apart from scores of deconstructed essay films by virtue of the formal integrity of its component elements. Text, soundscape, and cinematography each pull at an eccentric Florida artist’s rotting dream world. Karen Yasinsky’s The Man from Hong Kong (2015) frames its lush montage of fashion pinups, home movies, and kung fu sound effects with an odd close-up of a dog blinking in the sun—an apposite image for the Crossroads experience. (Strange to say, I’d never really considered how we squint both to shield our eyes and to strain for a better view.) Michael Robinson’s Mad Ladders (2015) is merely virtuosic, tunneling through a beautifully variegated montage of ’80s music television as a woman’s voiceover waxes prophetic. I’m tempted to see the film as a prequel to the fluorescent post-apocalypse of Circle in the Sand (2012), but, regardless, Robinson’s interpolations of televisual textures go way beyond nostalgia. I had seen Ben Russell’s YOLO (2015) before, but its doubly participatory approach—a collaboration with Soweto’s Eat My Dust youth collective that insinuates the audience through a series of frame-breaking gestures—felt especially vital in the context of so many introspective films.

Mike Stoltz, Half Human, Half Vapor, 2015. 16mm, 12 minutes

Not that introspective necessarily means timid: see Nazli Dinçel’s Her Silent Seaming (2014), which sliced through an otherwise hazy afternoon program. Scored to the direct sound of splices and scratches, the piece runs a few distressed images between text etched directly into the body of the film—“a transcription,” per the filmmaker’s note, “of what I have been told during intimate experiences while separating from my husband.” Each line zeroes in on a moment the mask slips: “He says,” begins one, “You have no reason to feel self-conscious.” Dinçel evokes several iconic strands of embodied cinema, as well as apparently cannibalizing material from one of her earlier projects, but in both form and theme, the goal seems to be exorcism rather than mastery.

Zach Iannazzi, Old Hat, 2016. 16mm, 9 minutes/

My other Crossroads favorites worked more circumspectly. Zach Iannazzi’s Old Hat (2016) was projected in-house, and the intimacy of the presentation offered a clue to its relay with the audience. The film opens with a languid series of compositions separated by leader, the camera stopping up and down as if in and out of sleep. Fireworks, low sky, open road: the subjects are indeed “old hat,” suggesting a filmmaker contemplating both his materials and his influences. Each image seems to offer a door into a different kind of film, but then of course this air of indecision is an illusion since we are after all watching a finished film. As if to mirror this recognition, Old Hat abruptly tips into a free-fall of emulsion, color, and image-traces: whatever the difficulty of finding a way forward, film does nothing but. A final cluster of shots shows a glass skyscraper both against and mirroring the sky, such that the blue day is twice transposed onto a flat screen. It’s the detail of a window washer’s platform that stays in my mind: a distinctly modest figure for the filmmaker’s work, not so much making the world as clearing its reflection.

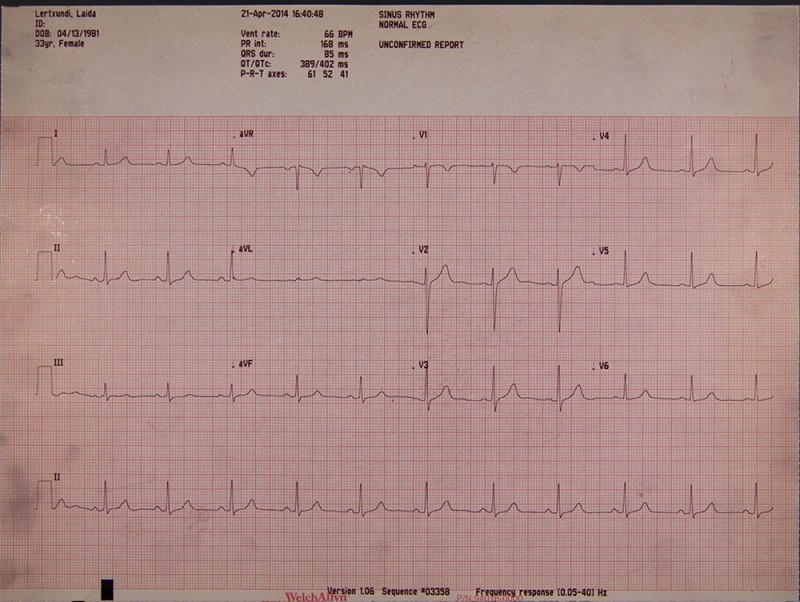

Laida Lertxundi, Vivir Para Vivir/Live to Live, 2015. 16mm, 11 minutes

Laida Lertxundi’s Vivir Para Vivir/Live to Live (2015) similarly delights in the paradoxical notion of a film escaping itself. Where an earlier generation of filmmakers dealt sternly with the “problem” of representation, Lertxundi recognizes it as a question of degree—and thus an occasion for play. A flattened view of rugged California mountains is juxtaposed with the peaks and valleys of the filmmaker’s electrocardiogram (a representation of the inner landscape no less graphically pleasing for being scientifically conceived). The sound of a heartbeat merges with a pop song. Stray images of cacti, pickles, and a woman bowing her cello seduce the senses while foregrounding their material nature as shots in a film. The film concludes with a volley of pink and blue frames, the colors apparently timed to an audio recording of a woman’s orgasm. This review joins all the others in disclosing this irresistible detail, but the fact is you wouldn’t know it by just watching the film—which makes it a secret, and a secret wants out. Perhaps all of Vivir Para Vivir/Live to Live’s efforts at translation and transposition finally point to the underlying strangeness of Lertxundi’s personal images becoming someone else’s. The shot may fail to fully capture the experience (whatever that could mean), but in so doing creates a new order of intimate experience as cinema. It’s in a more positive sense, then, that Lertxundi’s representations leave something to be desired.

Jonathan Schwartz was back at Crossroads with a pair of films, longer than last year’s miniatures but no less light on their feet. Winter Beyond Winter (2016) confirms his gift for lyrically transposing what’s close at hand, in this case drawing a reverie of fatherhood from the short, sharp days of New England winter. The camera moves from laden trees to dazzled earth while on the soundtrack a boy reads from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. How strange it is to hear this text in the child’s slightly bored voice, innocent of the narration’s buried heartbreak. From here we follow an older man carrying skates and a boom mic into the woods. He turns a few elegant arcs around a small pond, the camera watching from the side before shaking off its melancholy and taking to the ice. One skater holds the image, the other the sound; the shot is their union. As Martin Buber wrote, “All real living is meeting.”

Jonathan Schwartz, A Mystery Inside of a Fact, 2016. 16mm, 17 minutes.

Where Winter Beyond Winter is thrillingly clear, A Mystery Inside of a Fact’s sounds and images rise from fathomless depths. The film was shot in India, but its subjects are unmoored from ethnography. Low-angle shots of a coxswain set the course for the film—its unseen current and dark swells. A woman’s voice reflects on the elephant’s capacity for self-awareness, suffering, and suicide, while superimpositions picture the animal as a wandering soul. Fifteen years ago, Schwartz was in India recording sound for Kolkata (2001), a miraculous actualité film made by Mark LaPore, a beloved filmmaker and teacher who ended his own life in 2005. That film climaxes with a breathtaking tracking shot through the city’s streets, a river of life punctured by flashes of self-consciousness, but Schwartz’s camera stays to the side of the road. A boy flashes a peace sign—cut. Another dances in a darkened room—cut. The soundtrack is someplace else: every shot an interior, no matter the setting. Vashti Bunyan’s “I Don’t Know What Love Is” finally emboldens the camera to take cover in a couple’s embrace. Bunyan’s demo, recorded when she was in her early twenties, breaks its own heart at the thought of a lover’s inevitable departure. Schwartz approaches it from the other side of loss. The logic by which A Mystery Inside of a Fact arrives at this tender coda remains obscure, but its necessity shines through.