Devin Troy Strother knows how his work can be perceived and he’s not afraid to talk about it. I joined Strother in his LA studio, where we discussed the unique references in his work, and how he situates himself within the art world, the art market, and the black community.

Devin Troy Strother: Both of my parents worked all day so I was basically raised by television. They would just leave me at home with the television on so I watched a shit ton of TV and a lot of movies all the time.

Lindsay Preston Zappas: That’s kind of a suburban condition, right, to be a latchkey kid? Do you watch TV a lot in the studio?

No, at home after I leave the studio. I have this publishing company called Coloured Publishing that my girlfriend Yuri and I started and work on at home. Basically, I watch TV whenever I’m at home, working on a book. I’m kind of hard of hearing so I play shit really loud, which my girlfriend hates. I used to go to a lot of shows when I was younger so I fucked up my ears. I listen to music really loud in the car. I play everything really loud. We started living together and it’s usually just me drawing until 4 in the morning, blaring the TV (usually comedy specials) or podcasts hosted by comedians like Marc Maron, Joe Rogan, and Doug Benson, to name a few. I think a lot of my work comes out of that. A lot of the titles have an aspect of me trying to be a comedic storyteller—almost like the title is a one-two punch line to the visual element. The piece is the set up and the title is the punch line.

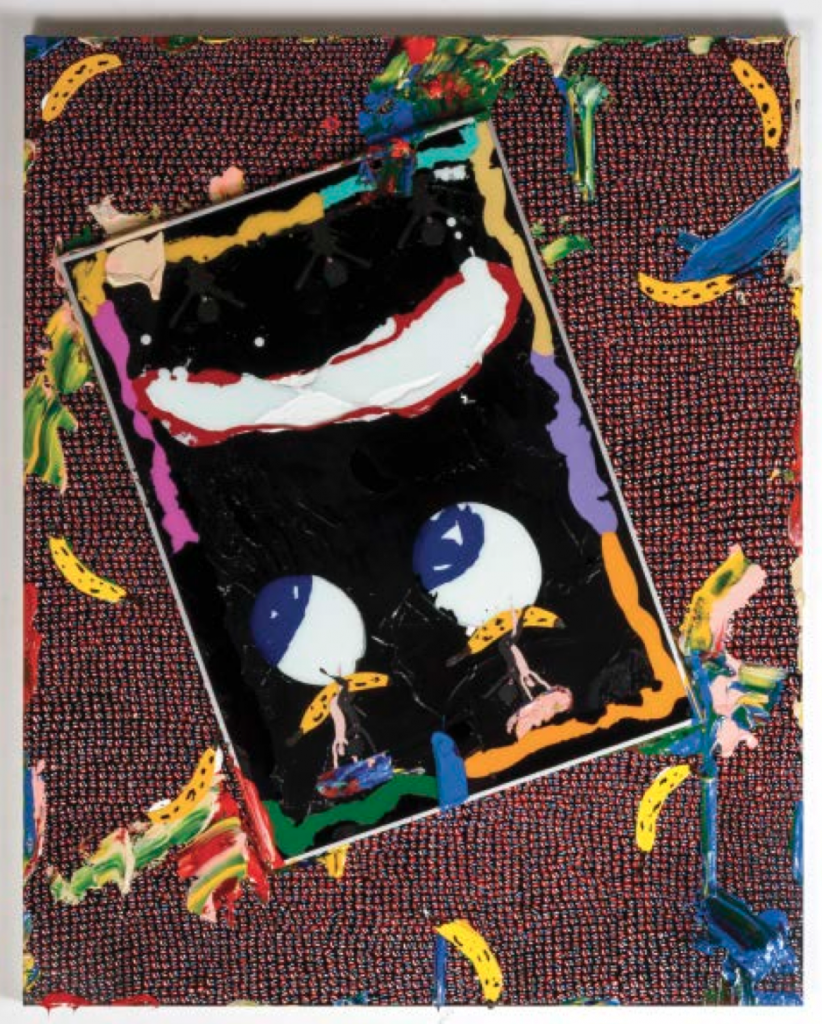

Nigga I’m getting light headed, can we stop now? (no nigga this is art), 2015. Acrylic, cut paper, and IKEA frame on panel, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

4 niggas on a plate (where’s my abstraction), 2015. Autobody paint and acrylic on aluminum, 66.75 x 16 x 16 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

I’m curious about where the language comes in—the one-two punch—because I feel the humor you’re using is a bit subversive. One-liners can be taboo in the art world, right?

Well, one-liners and comedy in general are pretty subjective, so I don’t know if they’re necessarily taboo within the art world. I think a lot of the language in my titles comes from being a black artist. A lot of times work will go into a serious place or get complex when you talk about race issues and being political. There’s always different genres for different black artists to pick. Kara Walker talks a lot about slavery, or Kerry James Marshall has a very particular vernacular about talking about black culture, or Glen Ligon, or David Hammons. They all pick a particular way of talking about being black. I feel that sometimes it becomes a conversation that is heavy at times; it gets a little bit much. I try to make work that celebrates a different vernacular of being black. When I was growing up in the ‘80s it was cool to be black, whereas when my dad or my grandpa were growing up it was probably different, you know? So I feel like it’s just a different take. It’s not like everything is a one-liner, but when I’m making the work that’s how it is in my head. There’s a lot of other shit that’s going on in the work, but I guess the way it’s presented, you don’t have a lot you can really say to the viewer in between the title and the actual piece, so what you’re going to do with those two items is very important.

I think your work is coming from this younger perspective where you don’t feel the same urge to embed so many strong political views—but I’m wondering if you think about your work as progressing or responding to political and racial issues.

I do think about that a lot; it becomes a burden for me sometimes. Not to put me on the same level as him, but I did an interview recently and we talked about Dave Chappelle and why he stopped doing the Chappelle show. [I think about my work] along those same lines. What am I actually doing for black culture? Am I helping further us or am I holding us back by portraying black people in a certain way, you know? If you think about black culture in the ‘90s it was very high tension, and it’s still high tension now. There’s always something, and it’s always heavy, and it’s always this thing that feels like a burden on black people. If I’m going to have to talk about it, I want to talk about it in a way that’s at least going to be fun for me. I’m going to get called out for whatever, but I don’t know—I mean, I don’t know how to talk about it without—black people, we’ve always capitalized off of our own struggle, quote/unquote. We struggled so hard and we got here and so I don’t know, it’s so much shit to have to answer for. You just get bummed out, like fuck, how am I going to talk about race in this piece? Or, do I even want to talk about race? These are always questions that are floating around in my mind while I’m working on a piece.

To go back to talking about the titling, I was looking at a couple pieces in particular where the paintings are more abstract, or have certain shapes being repeated, but then the title adds a racial element that wouldn’t have been culled from the aesthetic of the painting.

The titles have always been a way to offset whatever’s going on in the painting, like a counter balance in a way. The image may read one way and the titles can take it somewhere totally different. The paintings have a naïve quality/style that I’m comfortable working in, and the titles are a way to try to give the work some criticality or to offset the style I chose to paint in.

What about the paintings feels naïve?

Well, I went to school for illustration, so I do know how to paint, but I just choose to paint this way. I’m not a great figurative painter or anything, I’m no Gerhard Richter, but I do know how to kind of paint. I choose to do this more simple, stripped down way of painting. Recently I’ve been trying to break out, even getting away from using the blackface motif. I’ve slowly transitioned out of using that so much, but recently I’ve transgressed and am overusing it. I’ve recycled the blackface image so many times and used it so many times. I made carpet using it. It’s definitely a thing for me now where it works as signage. For some people it’s really loaded, and I’ve said this so many times. Some people see the blackface and know the reference that it comes from—Golliwog, minstrel shows and all that shit—and some kids have never even actually seen it. Then some people, collect and actually love Golliwogs, or have a fetish for them. So for me, I like using it because it’s loaded and I don’t really have to inform people about what that means.

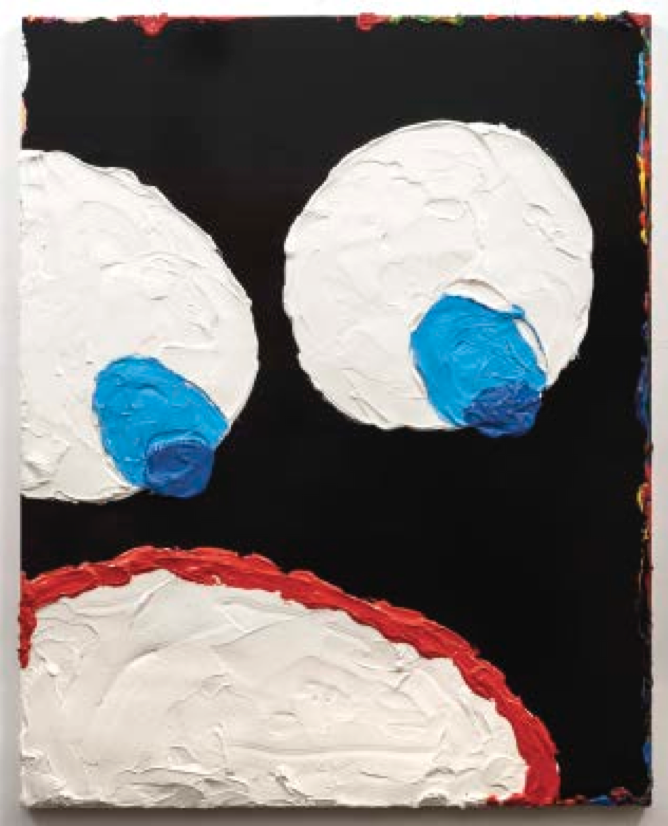

The big face nigga part 1, 2015. Acrylic on panel, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

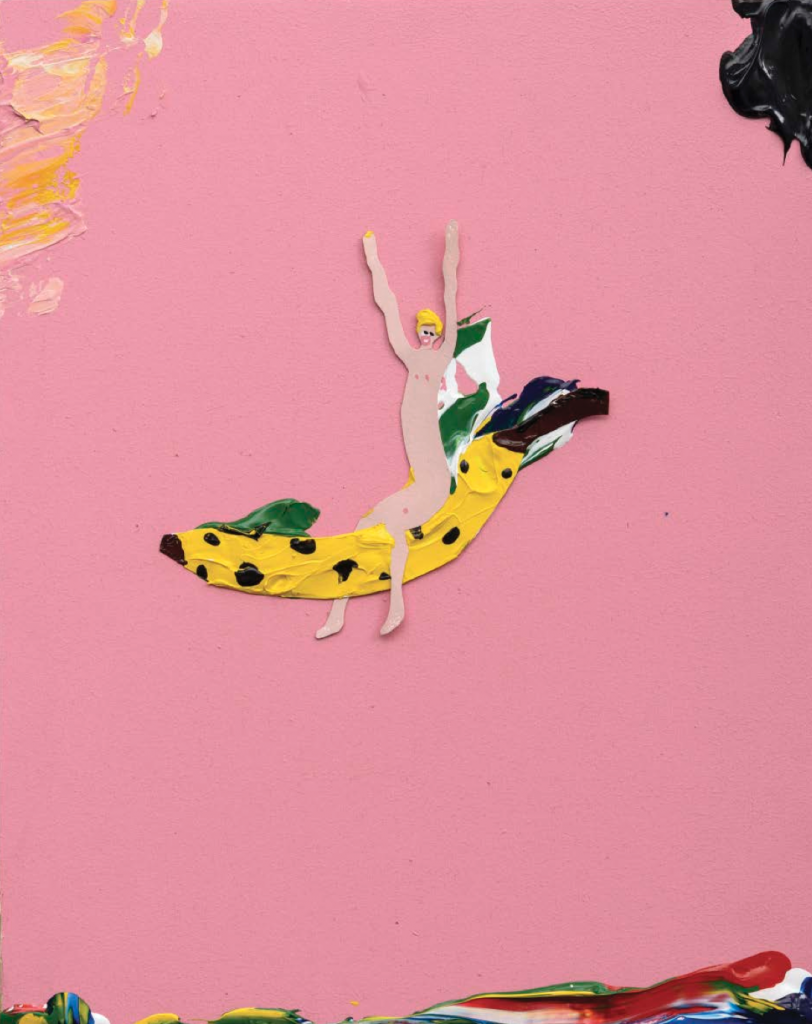

Nigga on a nana, 2015. Mixed media on panel, 17.5 x 14 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

I’m curious about the female body, another repeated motif in the work. Can you talk about the female posture and the choice to use the nude female body specifically.

Basically, how I see it, I’m continuing the tradition of depicting the nude female body. It’s a classic theme that’s always been in every genre of figurative painting. I have no interest in commenting on sexuality, although that will obviously always be talked about by viewers, just like race. When you learn how to draw in school and you do figure drawings, those are the classical poses that models do for learning how to do gestures and shit like that. So a lot of those poses I did in the very beginning came out of old figure-drawing poses. The one that I do mainly is the girl on her arm. That one is based off of a couple things—when I was growing up, there was always Egyptian art in black homes and shit. My mom had a bunch of Egyptian art and it’s just a weird thing that black people always have photos of like Nefertiti or the Sphinx. You know Tupac had the tattoo? So that pose is based a little bit off of the Sphinx. And also kind of the pose in gesture drawings—that one’s obviously a little bit more sexualized, so it’s a little bit of both of how women have been fetishized, but how it’s also iconic at the same time. It’s the same thing I do when I do guys. They don’t have a penis. It’s just a dot that’s right there.

What is your relationship to feminism? I don’t know if anyone’s ever asked you that before.

No one’s ever asked me that before. I don’t even really know how to answer this question. What’s the blanket meaning of feminism—believing women should have equal rights? If so, then automatically, I’m a feminist. All I can say is, being a black male in the art world, I can relate to a certain extent with women, because we’re in a space that’s dominated by white males. If you look at enough gallery rosters, you’ll see a common thread: one or two black artists (two is really uncommon), maybe two or three women artists, and the rest are white males. Why? Do you think my work is exploitative of women? You can be honest with me.

I only ask because I think how you’re using women is pretty celebratory, almost similar to Mickalene Thomas—her style of depicting women in this very ornate and adorned way. Yet, the nudity also strips the women from any signifying class discussion.

What Mickalene does with the female form is a different conversation from the one I’m having in my work. It is definitely celebratory of the female body, but it’s also, like I said before, a reference to the history of the female nude in figurative painting, especially in the Baroque and Romantic periods. The women have not always been naked. If you look through my work, there are years and years where they’re fully clothed. In recent years the clothes have been coming off both men and women. It’s just a stylistic period I’m going through right now.

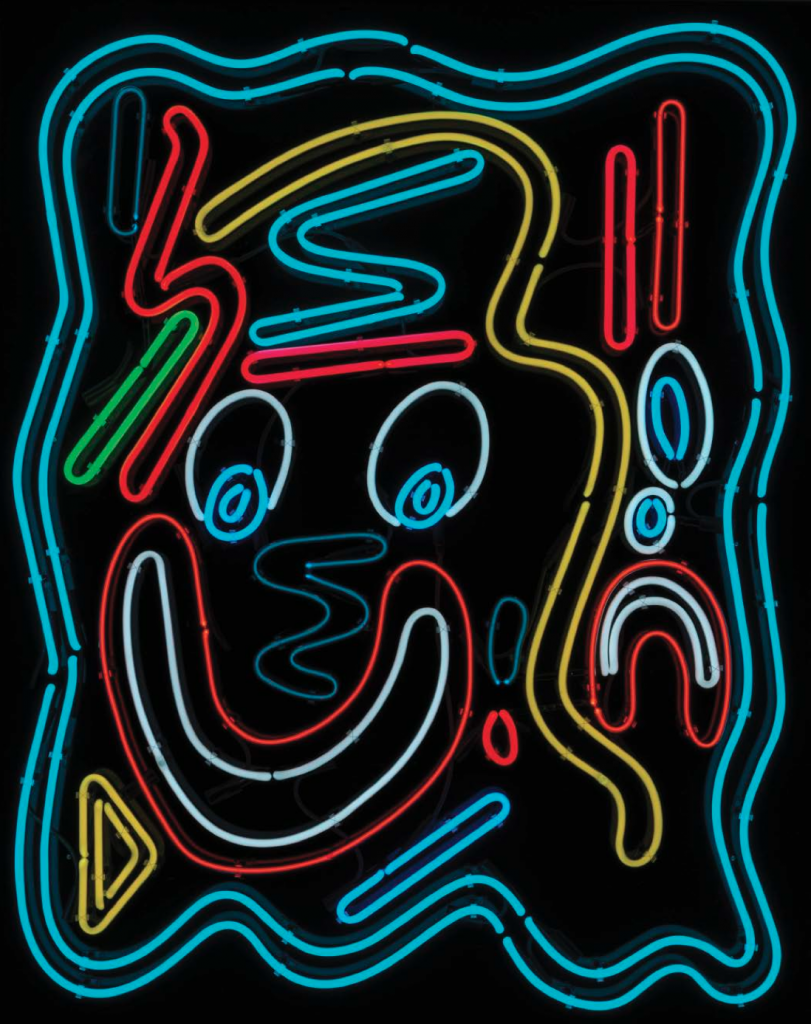

I wanted to talk about the neons in the Richard Heller show. There’s something about neon that almost evades color in a way. It becomes sort of a non-color. It becomes something that signifies—

It’s a symbol of color.

Right. So then to do the blackface image in that material . . . does the color represent the racial—

The thing with neon, I’m really into using things that are just basic colors. The way I paint, I don’t really mix color, I just use color straight out of the tube. And so neons work in a similar way, where there’s only twelve colors you can really get. They can add other gases to make other shit, but it’s a very limited palette. So when I started using neons it was more me just trying to paint with fucking neon. I would bend weird shapes and then try to replicate that into a neon or whatever. Just picking a color, seeing how it looked and rearranging it, it was really fun, actually . . . like making a painting with colored glass.

Black neon abstraction (nigga you crazy) #2, 2015. Neon, 59.5 x 47.5 x 5.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

Do you resent the fact that people read race into the work, like I just did? You’re talking about this use of neon as this playful material, and for me I read, “Oh, he’s choosing to distort the coloration of the skin.”

Yeah, that’s the thing. When you’re black and you become an artist you’re always going to have to answer for your race. If I painted nothing but white people the question would come up why don’t you paint black people? You always have to answer for it. So I figure if I’m going to have to talk about being black I want to do it in a way that at least it’s going to be kind of fun for me. So that’s why the work is so over the top in so many different ways. But then I have to talk about all this shit that has to do with being black. So this piece, I was trying to not use any figures at all.

Let’s talk about these paintings over here that are a bit more abstract.

These are called Paintings on Top of Paintings on Top of Paintings because I’ve been doing a bunch of small paintings. They sell these little hobbyist—

The mini canvases on the little easels!

Right. So they started as a way for me to get kind of loose when I get into the studio. They’re ridiculously small canvases and don’t feel like anything substantial, so when I started doing them they were sketches for what could be larger paintings that I’d never make. Over time as I amassed a number of these quick little paintings, I started placing them in a sequence, as if they were little paintings on a board, and you could choose which one you want. But when combined, all the little pieces become one big piece. Each one of these could be an actual painting if I wanted to do them at a larger size. But since they’re mainly abstract or don’t usually depict figures, I don’t know how to make them work on their own as individual pieces. It’s still something I’m grappling with within my practice.

Is that a way for you to be subversive toward the market? These small scale paintings?

No, because I’m not selling the individual canvases. They’re considered one piece. If we want to start talking about the market and working with galleries, that’s a whole other monster. Part of that monster is supplying demands, like people requesting work I’m no longer making or work I’m no longer interested in making.

How do you respond to that? Is that okay for you?

It’s okay at times, depending on what the collector is requesting of me. People say things like: “I want 1200 niggas in space, but can you do a little abstract paint swoosh across?” I’m like fuck, do you want to just come and make the painting yourself? But I’ve had that. They’ll send me two paintings and be like I want something that’s like these two put together. What the fuck? I’m going to just make you whatever the fuck I make but sometimes it gets hard to accommodate certain commissions, because I’m not really into doing—

What they ask?

Yeah, exactly. When you’re still an emerging artist, you have to ask yourself, “Do you do the commission exactly the way the collector wants it?” Or do you have some type of conviction to say “No, that’s not what I’m making!” But it’s hard to say no when you have studio rent to pay.

So do you feel you straddle that?

I can now. I’ve got a little something going so I can be like, “I don’t really want to do that, but I’m doing this.” Right now I’m going through a transition from doing these narrative-based, very small, intimate paintings, and I’m doing these larger, more abstract or pattern based works. When you change directions in work collectors sometimes get scared and they want to get the old thing before you go on your bad riff—“before you go into performance art let me get—before you kill your career let me get this painting.”

![Contemporary African Compositional Arrangements, "Guuuuuuurl you need to consider the gestalt of perceptual organization" (detail), 2012. Acrylic, enamel, wood and construction paper on paper, 45 x 30 inches. SFAQ[Projects] Pullout Poster, Issue 23.](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Screen-Shot-2016-03-06-at-7.59.47-PM-533x1024.png)

Contemporary African Compositional Arrangements, “Guuuuuuurl you need to consider the gestalt of perceptual organization” (detail), 2012. Acrylic, enamel, wood and construction paper on paper, 45 x 30 inches. SFAQ[Projects] Pullout Poster, Issue 23.

I’m wondering if you can discuss your relationship to idol or lineage? You use the sports icon, Michael Jordan, as this recurrent motif, alongside references to famous artists, many of whom are white males. Is this a way for you to collapse the space between cultural icons and canonized artists?

To me, Jordan is this icon of black culture, but then he also sort of supersedes it as being an American icon of sports. I can talk about him and it’s about race, but at the same time it’s just about a guy who’s really great at basketball—it has nothing to do with his face. So it kind of does exactly what I’ve been trying to do: make work that has black figures in it, but without it being about race or divisions. Just to be as simple about it as possible, you know?

When Roberta Smith reviewed the show she asked why I didn’t reference certain artists and why I referenced the ones I did in my titles. How come I didn’t reference David Hammons or Ellen Gallagher? Why should I have, because they’re both black artists? Because I’m black, should I only be allowed to talk about black artists? The conversation that I was having was about the white artists that I was referencing. I feel like I don’t need to talk about Hammons or Gallagher because it’s already apparent they influence my work. I wanted to talk about certain white artists that are relevant within the art world right now, and how they dominate visual aesthetic trends.

Is that a way for you to be honest about the state of contemporary art? Where a lot has been done . . .

Everything’s been done.

So now our role is to regurgitate and re-appropriate.

But you have to be able to answer for it. You have to know who you’re referencing and you have to reference the right people. They want you to validate—like when I talk about neons I should definitely be talking about Dan Flavin, or Tracy Emin or Terence Koh, or everyone else that has used neon— how does the work relate and how have you elevated the usage of neon in work? Which is so hard to really try to do, especially when you’re doing it so publicly, showing new work, so quickly.

And when you say “they”, who are “they?” The critics? Collectors?

I would say more critics and institutions want you to validate—like you know, me being black I’m going to have to talk about how I fit in to the whole canon of black art. There’s a whole genre of black art and you have to pick and choose who you’re going to come after—I don’t know how to explain. Like David Hammonds choses to talk about being black in so many different ways, the performance with the basketball, you know what I mean? But that was definitely about being black, you know what I mean? Just by using the basketball, he talked about being black. So he did it in the simplest way with just that. I definitely want to further the conversation of what black artists can do and what’s not accepted of a black artist, or what’s expected of a black artist. I definitely would love to be a part of that conversation: it doesn’t always have to be about the civil rights movement or heavy handed. But like I definitely think about how my work is creating social change and how am I talking to future generations . . .

But you wouldn’t put that on any other young artist in LA, you know what I mean? Someone whose making sort of pop/abstract artwork, you don’t ask them how their art is affecting the next generation. As you’ve said, it seems that the critics will do that for you; they’ll put all of this loaded content on your work.

But also, if you don’t put it in sometimes they’ll ask why it’s not there. How come you didn’t reference so and so? You’re always going to have to answer for who other people think are important and who they see in your practice. Which I get, you do that with everyone, with any artwork, you go, “oh that looks like fucking Donald Judd and a little bit of—it’s like four artists all put together.” Everyone is an amalgam of a bunch of people now, you know? And I figured why not just be blatant about that as much as possible. It’s kind of funny, it’s what you’re supposed to be thinking about, but instead, just say it in the title or something.

Has anyone criticized this—you’re saying it’s a little tongue in cheek, right?

Definitely tongue in cheek, definitely.

You’re making fun of our system, but in that way you’re also kind of like biting the hand that feeds you because the system is paying your fucking rent, right?

I think the art world likes that. They kind of want to be made fun of a little bit, you know what I mean? Like who did that poster that said, “this is not for the rich white pigs” or something like that?

And then a white dude buys it.

It’s that whole thing that they want to be called out. I don’t know, like we were saying earlier, the art world is so different. There are so many artists who are really amazing and make great work and aren’t represented, and struggle and have to teach, and then you can say there are artists like me who maybe, from some other people’s standpoint, don’t make great work, but then I’m kind of doing okay. You know, a painter told me a long time ago that paintings pay the bills at galleries, and it’s a really true statement. That’s how you usually pay the rent is through paintings. Your crazy performance where you crawl on the ground reading your mom’s diary—you know, that’s really hard to sell. But a big black painting of a fucking backwards Nike sign over someone’s couch is going to look really nice as opposed to a sculpture of a bunch of bags of concrete on top of an old paint can or something. So galleries always have to have their people on their roster who make work that’s a little bit more for the market. That’s what keeps galleries able to show the more avant garde shit. So then when you get pinned as a market artist—

Do you think you’ve been pinned that way?

No, not really—no. I haven’t been making work that long I guess. But, you always have to think, am I making this for someone to live with? Or am I just making it for it to be out in the world? Those are two different modes of making. So if you’re making things for someone to live with, that’s a different way of thinking about what you’re going to compose, as opposed to just like if you’re just trying to make a statement and like really just like make something that’s going to be maybe a little bit—like a Ryan Trecartin piece, that’s something hard to place. It’s hard to place video and complicated installations—but it’s easy to place a giant Rothko or Laura Owens. And I don’t want to say that painting is like being an interior decorator, but I think sometimes the modes/motivation of what to put where could be similar. This is definitely something that crosses my mind when I think about what people buy. The work that you feel is good and what people actually buy are always two different things. So there’s that whole part of making work too, that once you start to sell shit you have to realize that okay, if I want to keep this going I actually have to be a little more calculated. It goes outside of the criticality of everything sometimes, and so how do I prolong this endeavor to keep going, you know? It’s a thing you have to think about.

I’ve seen a lot of young artists go the wrong way with it. Is that something you worry about?

It’s definitely something that’s on the forefront of your mind when your whole income comes from art sales. You have to consider the market in some way, shape, or form, whether it’s intentional or not.

It’s so hard because that paycheck comes in, and you want to go out to dinner. [Laughs]

You definitely want to spend that money on yourself in some kind of way, but what you should do is put that paycheck toward your practice instead of spending, you know, a thousand dollars on Yeezys and a sushi dinner.

Let’s shift and talk a little bit about your transition out of school into having gallery representation.

So in 2009 when I graduated, when Tumblr and blogs were really popular, me and my ex-girlfriend, we basically emailed all these Tumblrs that were art and design related and we just were like, “hey, we really love your blog, there’s this website we came across the other day of this artist we think fits your aesthetic, you should check him out.” And it was me, and we would do that again under another email address. We did that to like 60 Tumblrs and blogs. Maybe 30 of them re-blogged me, so overnight I was on a bunch of Tumblrs and shit. After that, Kanye West blogged about me, and then his agent called me about purchasing some work. Ultimately they didn’t get anything, but afterwards I suddenly started getting calls from galleries. It was really crazy.

Because you basically were prank calling blogs?

I don’t know if that was prank calling but it was definitely a calculated way of getting free advertisement. If it says contact, refer us anything that you like, why not?

That was the time for blogs.

It was during that time, so I did that. I was working at American Apparel’s print shop, overseeing the printing of the “Legalize Gay” campaign, and then like out of nowhere I started getting all these people asking me if I have work available, and then I was just selling out of the studio for a while and then I was contacted by Richard Heller Gallery. He got me into some really good collections right off the bat, which was really cool, and so I’ve been working with him for about seven years now.

You are pretty active on Instagram. Are you using the same logic? Free publicity?

Yes and no. Instagram is this narcissistic system of constantly putting content into the world. So it works as publicity but it can also be very personal at the same time. It’s different for everyone who uses it. I have a lot of young followers. Younger people tend to understand the whole dialogue. When I use the word “nigga” they know I’m not really trying to talk about race, but it’s implied. It’s just part of the dialogue of using that vernacular in an institutional setting that is characterized by bourgeoisie, affluence, etc.

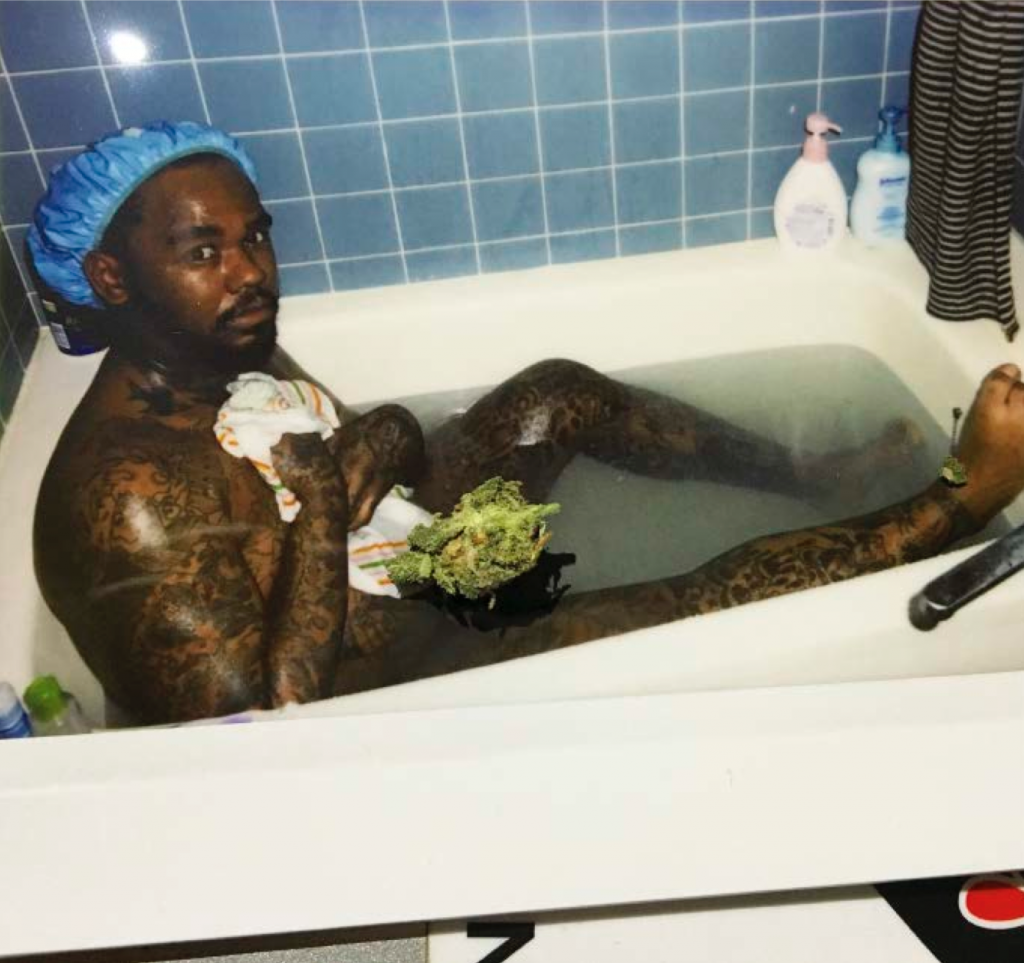

Portrait of Devin Troy Strother via his Instagram account, @devintroy. Courtesy of the artist.

The venue of Instagram is such a different thing. You’re flipping, you’re scrolling, you’re going from bright image to bright image, versus stepping into a white-walled gallery where the weight of history is always kind of embedded in this space.

Instagram is like a little gallery now though. You can see everything on your phone now. I didn’t have to go to any of the fairs that were here. I saw it all on my phone. And, it’s showing the work and having a critique, but it’s usually a positive because everyone just likes it.

There’s no unlike, or thumbs down.

Yeah, so there’s that whole thing too of like this automatic gratification of you posted a painting, people like it, and you’re like, “Awesome, I made a good painting. I did it, I made a good painting!” 200 people liked it, but then at the same time, like you could do the same thing and put up a painting you totally fucking hate and the same amount of things happen. It’s so subjective. You can test your work to see what people like. It’s weird, you know? It’s a new thing, but it’s definitely something you can do: you can see how people are reacting to your work without ever actually having a show.

When does that turn off for you? There’s this impulse of constantly being connected.

I mean there’s always this kind of need to post something. But I feel like it could definitely be a trap because you can get sucked into this mode of making work and posting it for the instant gratification of getting likes. It’s a temporary substitute for having someone come by your studio and exchanging in an actual discussion about the work. I feel like—because I don’t have a lot of people come over all the time, you know? Just because, not to get weird, but sometimes the space being so big, I don’t want people to—there’s been weird like, “How do you afford it?”

It’s funny because mainly—for a lot of artists, their Instagram is all their work and nothing that actually shows anything personal. It’s almost superficial and commercial. It’s like an advertisement for the work. I feel like how much longer am I going to be on Instagram? How much time am I going to do this for? Because it’s so much now and it’s so overwhelming.

But, it’s working for you.

I’m really fortunate that it’s working out for me right now, but it could be a temporary thing, like everything in the art world. I’m just so addicted to Instagram! And there are so many good memes now, it’s almost like a new form of artwork! Like the Bernie and Hillary ones, have you seen those? They’re really funny. What’s your stance on things—Bernie is always really positive and Hillary’s like—here, I’ll show you.