I assure you, my cemetery has no recollection

Of unmarked mass graves, scattered bone fragments;

That skull and cross-bones over the gate? Added by Disney—

Leftover prop from Zorro. Adds a little romance.

—Deborah Miranda, from “Interviews with California Missions”

September 23, 2015

Today Junípero Serra is being canonized by Pope Francis in Washington DC. Fr. Serra is the Franciscan friar who started the missions in present-day California and was thus responsible for the resettlement and Christianization of the Native populations here, including countless deaths, beatings, rapes, imprisonment, and the repression of cultural practices, languages, and traditions. For most descendants of these California natives, it is clear this man was no saint. The pope has his reasons of course, and for the first new-world pope, honoring the Spanish settlers of California is a way of honoring all of the Spanish-speaking Catholics of the United States, many of whom followed in Fr. Serra’s footsteps by walking north into California from Mexico. Yet the sanctification of colonial domination underlines many unanswered questions in the history of the lands we occupy and other territories around the world. In some sense these issues have been buried, particularly in the United States, by the marginalization of the native population and alienation of these people from their traditional lands. Colonial displacement has often been made invisible by countless historical changes that have occurred, but artists continue to disinter meaning from the colonial encounter and the long shadow it casts across the landscape.

The advent of postcolonial studies has flooded the intellectual market with excavations of so many dimensions of the colonial past and its present ramifications in our ways of thinking and coming to terms with the world. For others, the term “postcolonial” itself is a misnomer because colonization continues unabated, sometimes in new forms such as social and economic marginalization, and sometimes as a persistent trend of outright domination exercised by the powerful on those whose resistance is at best ineffectual (think of the Occupied Palestinian Territories).

But I want to look at the postcolonial in a broader context, as a manifestation of our subjectivity today whether conscious or otherwise. We are all implicated in the postcolonial dynamic because most places on Earth have been colonized at least once and therefore our subjectivities have been formulated though a postcolonial lens, whether we realize it or not. The very ground we stand upon is the result of contestation, both of meaning and the will-to-power. To colonize a space is to take it away from those who previously occupied it, but it also includes changing the meaning of that space—into one of property—so that there can be no going back, no way to even imagine that which was lost because those ways of thinking about place and the alternative languages to describe it have been eradicated. Notwithstanding Ward Churchill’s proposal for the US to cede about a third of its territory to Native Americans in order to live up to the various treaties promising land to tribes, the habitus where the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas once lived is gone in a way that can never be retrieved.

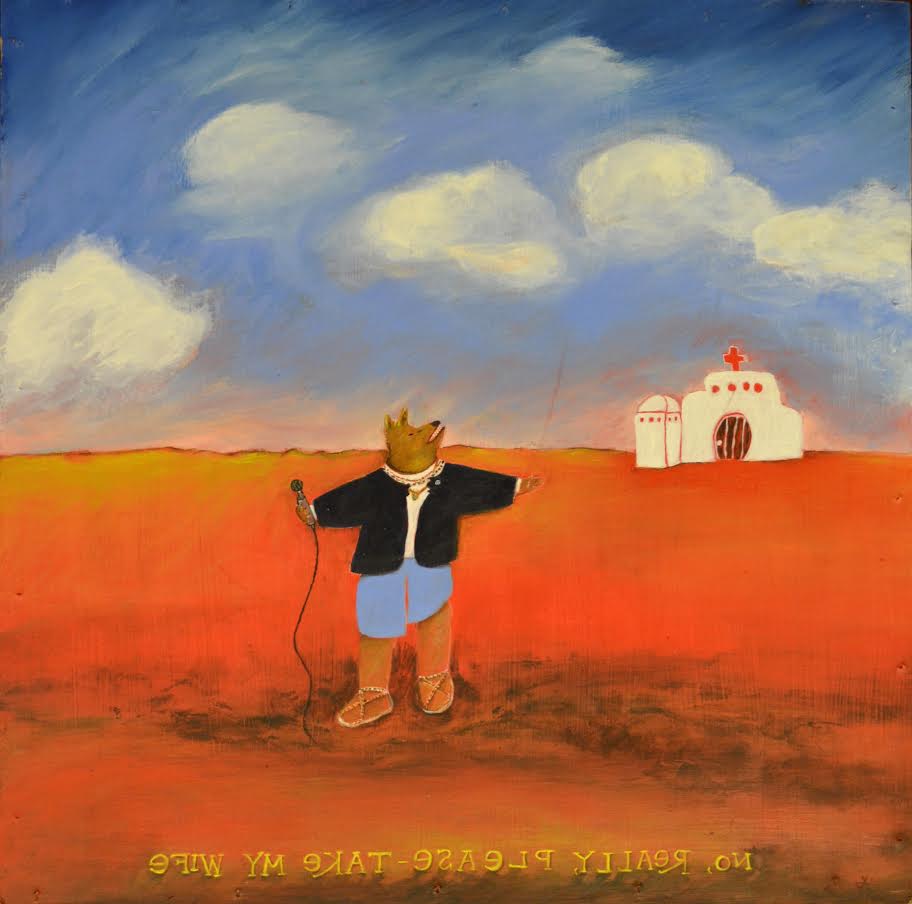

So we are all postcolonial now. The only question is whether we are willing to see, and to acknowledge it. Native American artists are responding to Serra’s canonization, and a recent issue of News from Native California (winter 2014), with James Luna acting as the arts editor, explores a variety of responses by Indian artists to the missions and their legacy. Many more events have been planned, including a Day of the Dead exhibition this year at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts, entitled The Bones of Our Ancestors: Endurance and Survival Beyond Serra’s Mission(s). The image the curators have chosen to advertise the call for artists is by L. Frank—a painting that was also featured in the News from Native California issue mentioned above—titled no, really, please take my wife (2012). It depicts a modern day Coyote, a mythical and literary figure in multiple Native American cultures and stories, dressed in sandals, shorts, and a jean jacket, holding a microphone in a barren, red landscape. Behind him on the horizon stands a comic-book mission. Looking at the clouds he says to no one in particular, “No Really Please Take My Wife.” These words are inscribed in reverse across the canvas underneath him. Since Coyote is known for his sense of humor, it is no surprise that he emerges into the present as a comic, making fun of the awful history behind the missions. The humor transforms this bitter and violent past into something we can laugh about because, in the end, what else is there? The artist is a descendant of the missionized Tongva people whose culture was so thoroughly shattered by the missions that the tribe cannot even achieve the foundations for federal recognition. To paraphrase the implications of the message here: “no please take my wife (and everything else besides).” What was the homeland of the Tongva is now known as Los Angeles. From such a tragedy is born dark humor.

L. Frank, no, really, please take my wife, 2012. Acrylic on board. Courtesy of the Internet.

But it is not only Native American artists who have explored the postcolonial contemporary. The Scottish artist Andrew Gilbert examines, in visceral terms, the glory days of the British Empire under the reign of Queen Victoria and Prince Edward. His pictorial antics owe much to German Expressionism, but also to military illustration and romanticized depictions of colonial conquest from films and television. Yet the images are the result of fantastic projection, a kind of re-imagining of the violence of colonial conquest as if it were played out in an entirely different way. Viewers are lured into considering their own relationship to the colonial past. In Gilbert’s Africa Destroys Europa (2013), an enormous monster—part zebra, part leopard, part dragon, with a skull for a head in the shape of the African continent—attacks, devours, and mutilates a legion of British soldiers who attempt to defend Buckingham Palace. The image is replete with signs of violence, such as the floating hand spurting blood that references a dark episode of colonial history: the practice of cutting off the hands of workers who were not productive enough in the Belgian Congo. Other sexualized imagery, such as the exposed black breast of the beast and the black penis emerging from the skull’s eye spurting semen, tease out the sexualized nature of Africans as attributed by European settler populations. Gilbert extrudes volatile imagery in vivid color here, but in a small inset—perhaps from the belly of the beast—he provides a parlor scene of two British officers smoking and examining a primitivist, expressionist painting while a severed black penis sits on the table in front of them. In this highly sophisticated faux-naïve style, Gilbert self-consciously disinters the violence of European colonialism in Africa while imagining an orgy of destruction if Africa were to reciprocate.

Andrew Gilbert, Africa Destroys Europa, 2013. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy of the artist.

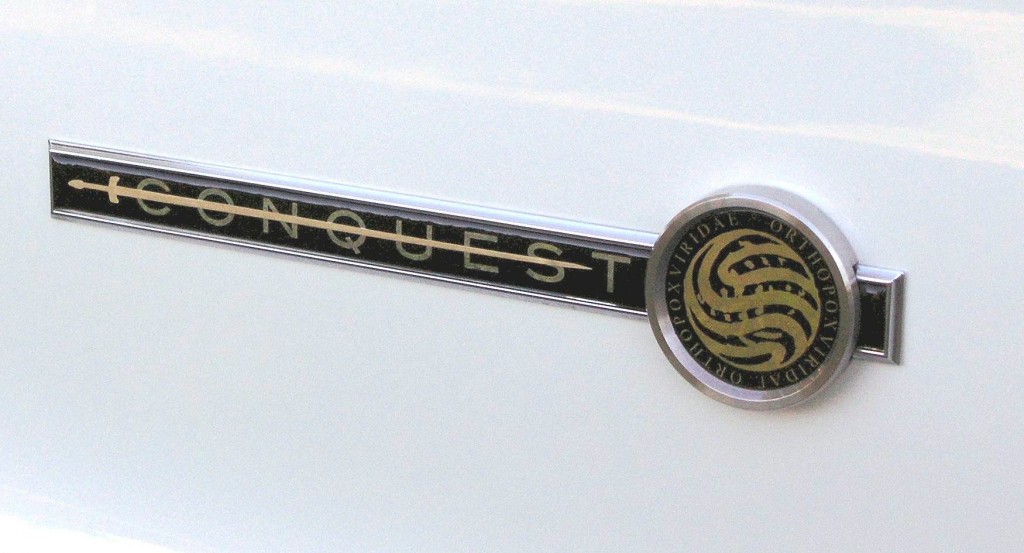

A very different kind of postcolonial contemporary is visible in the work of Lewis deSoto, a Napa-based artist of Cahuilla ancestry. DeSoto’s name has a dual reference, which he teases out in the sculpture Conquest (2004). On one hand, there is the American mid-century car company and, on the other hand, Hernando de Soto was one of the first conquistadors, whose trail of murder, rape, and destruction winds through both South and North America. The fact that a car company would be named after such a dubious historical figure is not exceptional. Cadillac is named after the French explorer (Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac) who built the first European fort in what is now Detroit, while Pontiac is named after an Ottawa chief who laid siege to the fort in 1763. Many American car models were named after Native tribes (Jeep Cherokee and Comanche, for example), to say nothing of state and city names throughout the United States that reflect traces of the loss of Native sovereignty and territory across the country.

For the artist, being an Indian named after de Soto is not a source of pride, but he turns this infamy on its head by creating an artificial DeSoto from a 1965 Chrysler New Yorker. (Chrysler headed the company from 1928 to 1961, when it perished from lack of sales.) The artist has lovingly hand crafted a variety of details that make this car unique. First of all, the vehicle shares characteristics with the Spanish conqueror’s legendary horse—the car is white with a black textured vinyl top, like a white horse with a black-haired man atop. Further, the interior is filigreed with touches of gold that reference the conquistador’s quest for El Dorado that led him to extinguish so many lives. A relief portrait of the Spaniard is inset into the steering wheel. Other details on the exterior reference colonial conquest, such as a small inlaid marquis (Conquest) with a sword and an image of the smallpox virus that decorate the rear fenders. Finally, the artist has reprinted the Spanish Requiremento of 1513, which established the laws for indigenous inhabitants of the Americas in relation to the Church and the Crown of Spain. The gist is: submit or die/be enslaved, and if you resist it will be your own fault. This is listed in the fine print on the price sheet that is attached to the window.

Lewis DeSoto, Conquest, 2004. Mixed media sculpture. Courtesy of the artist.

Lewis DeSoto, Conquest (detail), 2004. Mixed media sculpture. Courtesy of the artist.

DeSoto’s tongue-in-cheek homage to colonial decimation in the Americas once again turns tragedy into humor. More importantly, it transforms recognition of the colonial past into the essential condition for the appreciation of his work of art. Consciousness of our postcolonial position becomes the aesthetic of this work, and in the classic sense of the term, the sculpture reveals for viewers the truth behind such an object of beauty. To confront the truth of our postcolonial present does not entail the same stakes for everyone. If your ancestors were nearly wiped out in the process of colonialism, such a truth is a burden to bear, but none of us can claim to be innocent because our city, our homes, and our countries once belonged to others. All artists who encourage us to confront this destructive and painful history allow us to come to terms with this reality: our present. The artists and other residents of San Francisco who are being displaced now are but the latest manifestation of an age-old trend for the powerful to seize what they want, no matter the cost for those who have no say. One response that I see regularly is a piece of graffiti on a freeway underpass in Oakland: “Occupy to De-Colonize.” As I drive along that postcolonial freeway I wonder if it’s possible, if we can actually de-colonize our present. At least that writer has seen the limits of our condition and has imagined an alternative. As artists take up this challenge of illuminating the postcolonial, they imagine and project the alternatives.