1.

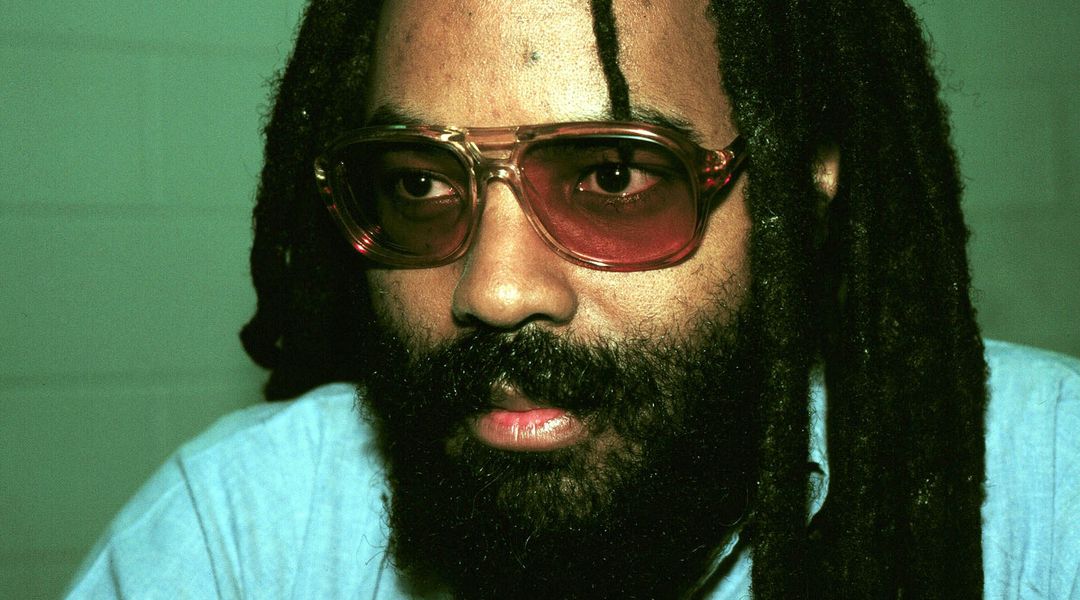

Christmas in a Cage

January 1982

Shortly before 6 a.m., the speaker in this tiny, barren cell blares a message, said to be from prison superintendent David Owens:

“A Merry Christmas to all inmates of the Philadelphia prison system. It is our hope that this will be the last holiday season you spend with us.”

A guard reads Owens’s name and the speaker falls silent for a half hour. I wonder at the words, and ponder my first Christmas in the hospital wing of the Detention Center.

Christmas in a cage

I have finally been able to read press accounts of the incident that left me near death, a policeman dead, and me charged with his murder. It is nightmarish that my brother and I should be in this foul predicament, particularly since my main accusers, the police, were my attackers as well. My true crime seems to have been my survival of their assaults, for we were the victims that night.

To add insult to injury, I have learned that the forces of “law and order” have threatened my brother and burned, or permitted the burning of, my brother’s street business. Talk about curbside justice! According to some press accounts, cops stood around the fire joking and then celebrated at the station house.

Nowhere have I read an account of how I got shot, how a bullet happened to find its way near my spine, shattering a rib, splitting a kidney and nearly destroying my diaphragm. And people wonder why I have no trust in a “fair trial.” Nowhere have I read that a bullet left a hole in my lung, filling it with blood.

Nowhere have I read how police found me lying in a pool of my blood, unable to breathe, and then proceeded to punch, kick and stomp me—not question me. I remember being rammed into a pole or a fireplug with police at both arms. I remember kicks to my head, my face, my chest, my belly, my back and other places. But I have read no press accounts of this, and have heard tell of no witnesses.

Nowhere have I read of how I was handcuffed, thrown into a paddy wagon and beaten, kicked, punched and pummeled. Where are the witnesses to a police captain or inspector entering the wagon and beating me with a police radio, all the while addressing me as a “Black motherfucker”? Where are the witnesses to the beating that left me with a four-inch scar on my forehead? A swollen jaw? Chipped teeth?

Not to end prematurely, who witnessed me pulled from the paddy wagon, dropped three feet to the cold hard earth, beaten some more, dragged into Jefferson Hospital, and then beaten inside the hospital as I fought for breath on one lung?

I awoke after surgery to find my belly ripped from top to bottom, with metallic staples protruding. My penis strapped to a tube, and tubes leading from each nostril to God knows where, was my first recollection. My second was intense pain and pressure in my already ripped kidneys, as a policeman stood at the doorway, a smile on his mustached lips, his name tag removed and his badge covered. Why was he smiling, and why the pain? He was standing on a square plastic bag, the receptacle for my urine.

Am I to trust these men, as they attempt to murder me again, in a public hospital? Not long afterward, I was shaken to consciousness by a kick at the foot of my bed. I opened my eyes to see a cop standing in the doorway, an Uzi submachine gun in his hands. “Innocent until proven guilty”?

High-water pants and cold

Days later, after being transferred to city custody at Giuffre Medical Center under armed police guard, I was put into room #202 in the basement’s detention unit, which is the coldest in the place.

After I was transferred to what’s laughingly referred to as the new “hospital wing” of the Detention Center, I found out what “cold” really means. For the first two days, the temperature plummeted so low that inmates wore blankets over their prison jackets.

I had been officially issued a short-sleeved shirt and some tight high-water pants, and I was so cold that for the first night I could not sleep. Other inmates saved me from the cold. One found a prison jacket for me. (I had asked a guard, but he told me I would have to wait until an old inmate rolls, or gets out. So much for “using the system.”) Other inmates, and a kind nurse, supplemented my night warmth.

The prison issued one bedsheet and one light wool blanket. When I protested to a social worker, she told me defensively, “I know it’s cold, but there’s nothing I can do. The warden’s been told about the problem.” Why am I concerned about the cold? Because the doctor who treated me at Jefferson Hospital explained that the only real threat to my health was pneumonia, because of my punctured lung.

Is it purely coincidental that for the next week I spent some of the coldest nights and days of my life? Is the city, through the prison system, trying to kill me before I go to trial? What do they fear? I told all this to my prison social worker (a Mrs. Barbara Waldbaum), and she pooh-poohed the suggestion.

“No, Mr. Jamal, we want to see you get better.”

“Not hardly,” I replied.

Miraculously, after my complaints, some semblance of heat found its way into the cells on my side of the wall. Enough to sleep, at least. Is it coincidental, too, that the heat began to go on the night I was visited by Superintendent David Owens?

“It is our hope that this will be the last holiday season you spend with us. . . .” Owens’s words ring through my mind again—is there another, grim meaning to this seemingly innocuous holiday greeting?

Echoes of Pedro Serrano

There is another side to this controversial case that people are not aware of. My cell is reasonably close to the place where Pedro Serrano was severely beaten and strangled to death. I have talked to eyewitnesses—some of whom I knew in the street. These brothers, at considerable personal peril, have told their stories to police and to prison officials, to city Managing Director W.W. Goode, to the Puerto Rican Alliance, and to me. Some have been threatened by guards for doing so, but they have done so despite the threats.

According to several versions, Serrano, who had already been beaten by guards, was shaking his cell door, making noise to attract attention. Guards, angered at the noise, ordered all inmates into lockup. Most complied. One, a paralyzed, wheelchair-bound inmate, did not. He drove his chair near a wall and watched in silence.

The guards opened Serrano’s cell, dragged him out, and proceeded to punch, kick and stomp him. He cried out in pain and terror, but the other inmates, locked up, were helpless. One guard, well known for his violence, reportedly whipped him with his long key chain, producing thin red welts in Serrano’s white flesh.

Before this latest assault on my brother and myself, I had covered a press conference called by the Puerto Rican Alliance and members of the Serrano family. I saw photographs of Pedro Serrano, his face swollen even in death. I saw a body riddled with swellings, bruises and welts. I remember the thick, dark bruises beneath his neck, and I remember calling David Owens for a comment.

“Mumia, Mr. Serrano was not beaten to death, according to all the reports I’ve received. The Medical Examiner concurs,” Owens said authoritatively. “Mr. Serrano was not beaten by any members of my staff,” Owens would later proclaim to my radio listeners.

Remember the dark bruise around Serrano’s neck? Owens told me he apparently strangled on a leather restraining belt, by exerting pressure until death. Inmate eyewitnesses said a guard wrapped the leather strap around Serrano’s neck and pulled him back into the room, where he was again beaten and placed in restraints. Serrano, arrested for burglary, was described by his wife as being in love with life, and surely not suicidal, as prison officials have suggested.

Why have I recounted these intricacies of a case that is now public knowledge? I’ll tell you why:

Because my jailers, the men who decide whether I am to leave my cell for food, for phone calls, for pain medication, for a visit with a loved one, are the very same men who are accused of murdering Pedro Serrano.

Remember the DA’s claim that police had enough evidence to charge me with murder? How much more evidence do they have on Serrano’s accused murderers? Yet every day they come to work, do their do, and return home to their loved ones . . . while others sit in isolation and squalor. Consider the scenario—accused murderers guarding accused murderers! How insane—yet how telling it is of the system’s brutality.

Justice for who?

What is the dividing line? That Serrano was a “spic,” a “dirty P.R.,” and thus his life is subject to the depredations of a system that talks justice yet practices genocide. I am accused of killing a policeman, who was, moreover, white. For that, not even the pretense of justice is necessary. “Beat him, shoot him, frame him, put fear into his family,” is the unwritten but very real script.

I have been shackled like a slave, hands and feet, for daring to live. Those who have dared to question the official version have been threatened with dismissal from their jobs, and some with death.

Why do they fear one man so much? Not because they loved his alleged “victim”—but because they fear any questioning of their role as accuser, and occasionally executioner. Who polices the police?

The DA is well known as a character whose only interest is higher political office—obviously he would oppose a special prosecutor, for he wants his office to have the glory of hanging murder on “the radical reporter.”

Where was [then-DA] Ed Rendell when Winston C.X. Hood and Cornell Warren were summarily executed, their hands shackled behind them? What credence did he give the witnesses to these murders? Or the outright, cold-blooded killing of 17-year-old William Johnson Green? Or the intentionally broadcast beating of Delbert Africa? Where was his unquenchable thirst for justice then? Need we mention Pedro Serrano?

Make no mistake, Jake! For a nigger or a spic, there is no semblance of justice, and we better stop lying to ourselves.

Who are we to blame? No one but ourselves. For we condone it and allow it to happen. We are still locked in the slavish mentality of our past centuries, for we care more for the oppressor than for ourselves.

How many more martyrs will bleed their last before we wake up, stand up, demand and fight for justice?

And justice, true justice, comes not from the good graces of the Philadelphia Police Department, the District Attorney’s office, the court system or your friendly neighborhood lawyer. It comes from God, the giver of your very life, your health, your air and your food.

MOVE members and police during the 1978 confrontation outside MOVE headquarters.

71.

Before Guantánamo or

Abu Ghraib—The Black Panthers

May 24, 2006

Long before the words Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib entered common American usage as reference points for government torture, there were several young Black men who knew something about the subject.

The year was 1973, and among 13 “Black militants” arrested in a New Orleans sweep were three men: Hank Jones, John Bowman and Ray Boudreaux. The three were beaten, tortured and interrogated by New Orleans cops, acting on tips supplied by San Francisco police. The men were stripped, beaten with blunt objects, blindfolded, shocked on their private parts by electric cattle prods, punched and kicked, and had wool blankets soaked in boiling water thrown over them. Under such torture, the three gave false confessions in the shooting of a San Francisco cop in 1971.

The charges were eventually thrown out after a judge in California found that the prosecution had failed to tell a grand jury that the confessions were exacted under torture. Today, over 30 years later, Jones, Bowman and Boudreaux have again been called before a grand jury, to try to resurrect what was dismissed in 1976. Imagine what these men thought when they heard about the U.S. government torture chambers in Guantánamo, or Abu Ghraib in Iraq. The names may have been different, but the grim reality was the same. Today, these men have formed the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights to try to teach folks about what happened so many years ago, and what is happening now.

Their living example teaches us that history repeats itself, but in worse, more repressive forms. That’s because their first conflicts with the state took place under the aegis of the since discredited Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO). That program, after the famous Church Committee hearings in the Senate, was declared illegal and a violation of the Constitution. Today, thanks to a Congress weakened by corporate largesse and frightened by 9/11, the same things that were illegal in the 1970s have been all but resurrected and legalized under the notorious USA PATRIOT Act. What we are seeing, all across the nation, is the emergence of what the late Black Panther Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver called “Yankee Doodle fascism”: the rise of corporate and state power to attack dissidents and destroy even the pretension of civil rights. I say pretension because the events I discussed earlier happened in 1973, yet none of the torturers, the violators, the criminals in blue, were ever sanctioned for their violations of state, federal and indeed, international law, to this day. Not one.

Think of this: the murderers of Fred Hampton Sr., those malevolent minions of the state who crept into his home and shot him dead (as he slept!) have never served a day, a minute, a second in jail for this most premeditated of murders, planned at the highest levels of government.

The roots of Guantánamo, of Abu Ghraib, of Bagram Air Force Base, of U.S. secret torture chambers operating all around the world, are deep in American life, in its long war against Black life and liberation.

Is it mere coincidence that the most notorious guard at Abu Ghraib worked right here, in the United States; here, in Pennsylvania; here, in SCI-Greene prison, for over six years before exporting his brand of “corrections” to the poor slobs who met him in Iraq?

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Panthers and others spoke about fascism, but it had an edge of hyperbole, of radical speech, to move people beyond their complacency. Several years ago, a political scientist who studied fascism on three continents came to some pretty sobering conclusions.

According to Dr. Lawrence Britt, fascist states have 14 characteristics in common. They are, briefly: 1) powerful nationalism, 2) disdain for human rights, 3) scapegoating to unify against “enemies,” 4) military supremacy, 5) rampant sexism, 6) controlled mass media, 7) national security obsession, 8) government religiosity, 9) rise of corporate power, 10) suppression of labor, 11) anti-intellectualism, 12) obsession with punishment, 13) deep corruption and cronyism, and 14) fraudulent elections.

How many of these features are reflected daily in the national life of the United States? What happens abroad is a grim reflection of what has happened here, albeit quietly. The tortures of Jones, Bowman and Boudreaux won’t be featured stories on Nightline, nor on (supposedly “liberal”) National Public Radio. (Remember the characteristic of “controlled mass media”?)

What happens overseas has its genesis in the monstrous history of what happened here: genocide, mass terrorism, racist exploitation (also known as “slavery”), land-theft and carnage. All of these horrors have been echoed abroad, shadows of hatred, xenophobia and fear, projected from the heart of the Empire outwards.

If we really want to change the dangerous trend of global repression, we must change it here first. For only then can the world breathe a deep sigh of relief.

106.

The Meaning of Ferguson

August 31, 2014

Before recent days, who among us had ever heard of Ferguson, Missouri?

Because of what happened there, the brief but intense experience of state repression, its name will be transmitted by millions of Black mouths to millions of Black ears, and it will become a watchword for resistance, like Watts, like Newark, Harlem and Los Angeles.

But Ferguson wasn’t 60 years ago—it’s today.

And for young Blacks from Ferguson and beyond, it was a stark, vivid history lesson—and also a reality lesson.

When they dared protest the state’s street-murder of one of their own, the government responded with the tools and weapons of war.

They assaulted them with gas. They attacked them as if Ferguson were Fallujah, in Iraq.

The police attacked them as if they were an occupying army from another country, for that, in fact, is what they were.

And these young folks learned viscerally, face to face, what the White Nation thought of them, their claimed constitutional rights, their so-called freedoms, and their lives. They learned the wages of Black protest. Repression, repression and more repression.

They also learned the limits of their so-called “leaders” who called for “peace” and “calm” while armed troops trained submachine guns and sniper rifles on unarmed men, women and children.

Russian revolutionary leader V.I. Lenin once said, “There are decades when nothing happens; there are weeks when decades happen.”

For the youth—excluded from the American economy by inferior, substandard education; targeted by the malevolence of the fake drug war and mass incarceration; stopped and frisked for Walking While Black—were given front-row seats to the national security state at Ferguson after a friend was murdered by police in their streets.

Ferguson is a wake-up call. A call to build social, radical, revolutionary movements for change.