Wavelengths: 2015 Toronto International Film Festival

September 10-20, 2015

The Wavelengths section of the Toronto International Film Festival is blessedly free of the Oscar buzz, expensive personal assistants, and celebrity lust otherwise clogging TIFF’s main arteries. This year’s program made for an especially pointed study in contrast by spotlighting Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, and Galen Johnson’s subversive behind-the-scenes takedown of Paul Gross’s big-budget warhorse, Hyena Road, which was itself the recipient of the red-carpet treatment elsewhere in the festival. Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton was relegated to a small installation in the TIFF Lightbox’s busy atrium, but that seemed perfectly fitting for this loopy work of termite art. Factionalism notwithstanding, Andréa Picard’s program continues to bleed more and more into the festival proper by encompassing feature-length narratives (Pablo Agüero’s Eva Doesn’t Sleep), disassembled autobiographies (Isiah Medina’s explosive if ultimately exhausting 88:88), docudrama hybrids (Roberto Minervini’s The Other Side, an unabashedly voyeuristic and surprisingly astute reading of the interrelationship of freedom and fear in American life), conversations (Tsai Ming-liang’s Afternoon), and unclassifiable epics (Miguel Gomes’ Arabian Nights trilogy) in addition to its traditional mandate of avant-garde shorts and installations.

Still from “Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton.” Dir. Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson, and Guy Maddin.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul. “Firworks (Archives),” Installation view.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cemetery of Splendour was rightfully included in the festival’s “Masters” section, but his Fireworks (Archives) installation flew under the Wavelengths banner. Shot in the director’s rural hometown in northern Thailand, Cemetery of Splendour centers on a school converted into a hospital in order to house a battalion of soldiers suffering a mysterious sleeping sickness. Regular muse Jenjira Pongpas Widmer tends to a soldier named Itt and strikes up a friendship with Keng, an attendant who uses her capacity as a spiritual medium to communicate with the soldiers. As ever in Weerasethakul’s films, mystical encounters flow in and out of small scenes of quotidian activity. Jenjira is surprised when two princess deities take human form to join her for a snack, but her co-workers hardly bat an eye at the story. A moment later, Keng is playfully prodding a sleeping soldier’s erection. Weerasethakul frames both spiritual and material concerns with the same even regard, evincing an underlying tenderness that finds its most magisterial expression in a scene in which Keng, possessed by Itt’s spirit, massages Jenjira’s lame leg. The audience is hardly immune from the hypnotic color effects generated by fluorescent rods beside each soldier’s bed, though some of Weerasethakul’s most mind-bending “special effects” are produced by verbal means. As the film becomes increasingly dreamlike, it incorporates more and more emblems of numbness and loss—the fruits of Thailand’s repressive military regime. The Fireworks (Archives) installation proved an important complement in this regard, for if Cemetery of Splendour’s gentle surface tends to sublimate political anguish, the 7-minute installation loop takes the opposite tack, with Jenjira and Itt wandering the cemetery’s statuary under a fusillade of fireworks and flashbulbs suggesting both onslaught and resistance.

Still from “Cemetery of Splendour.” Dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

Troubled sleep also pervades the intriguing double-bill of Nicolás Pereda’s Minotaur and Lois Patiño’s Night Without Distance. In the former, a slim feature shot entirely in Pereda regular Gabino Rodríguez’s apartment, three young intellectuals read aloud from books and nod off in strange positions. Insulated from the outside world except for interactions with a drug dealer and cleaning lady, their slumber is as much a figure of privilege as poetry. Patiño’s 20-minute film investigates the mountainous borderlands between Galicia and Portugal, a haven for smugglers. The human figures are folded into the terrain, which appears irradiated owing to Patiño’s careful inversion of color values. Night Without Distance develops a substantially new approach to the minimalist landscape film, one that fuses location and history as a kind of bardo state.

Still from “Night Without Distance.” Dir. Lois Patiño.

Ben Rivers’ Paul Bowles-inspired The Sky Trembles and the Earth is Afraid and the Two Eyes are Not Brothers plunges headlong into the border zone between reality and illusion. Beginning as a making-of piece filmed on the periphery of Oliver Laxe’s new production in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, the film starts comfortably in line with Rivers’ previous work in its open-ended observational mode punctuated by instances of reflexivity both direct (sleight-of-hand tricks performed for the camera) and implied (sudden cuts across space belying the apparently casual nature of the cinematography). Then Laxe abandons his set and enters a different movie. Kidnapped by bandits, his tongue cut out and forced into a costume of tin cans, the character is made to dance for his life and eventually sold off for a rich man’s amusement. Rivers is too subtle to present this oneiric fable as a straightforward allegory of post-colonial comeuppance (if anything, the increasingly stylized presentation of the filmmaker-cipher’s degradation suggests an irreducible element of masochism), and yet as an art-house midnight movie the film is itself an exotic object. I already feel a need to revisit The Sky Trembles…, but my first hit is that while Rivers remains compellingly unpredictable in his cinematic transfigurations of self, his latest work’s psychedelic turn smothers the finely tuned surrealism of his earlier efforts.

Still from “The Sky Trembles and the Earth is Afraid and the Two Eyes are Not Brothers.” Dir. Ben Rivers.

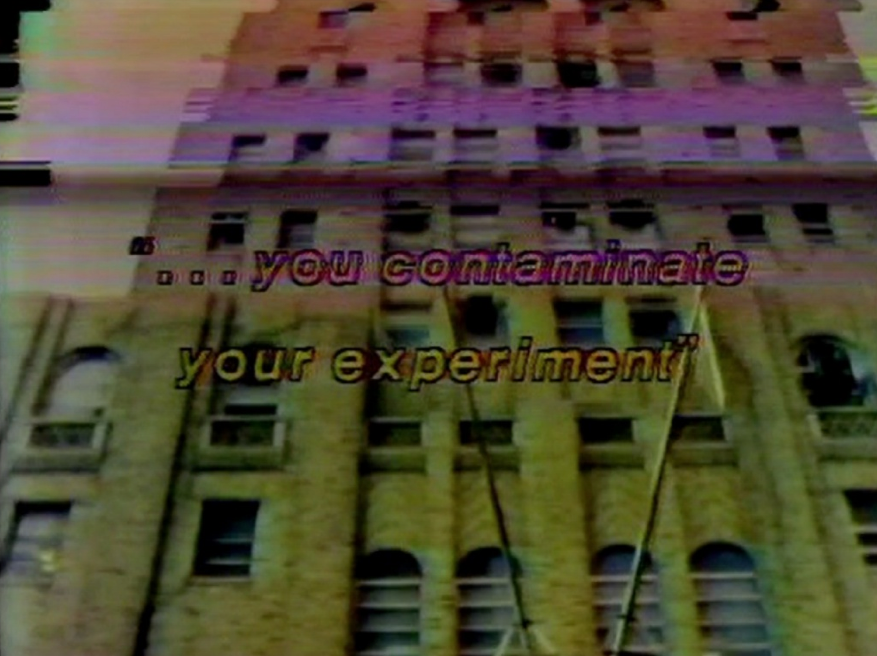

Wavelengths’ four group programs supplied plenty more fever dreams. Peter Tscherkassky’s The Exquisite Corpus lifts the hood on an indolent soft-core beach scenario for its materialist reckoning with voyeurism. Tscherkassky’s technique is virtuosic, but I still find that I am unable to muster much enthusiasm for his spotless deconstructions. William E. Jones delivers an altogether stranger détournement in Psychic Driving. By amplifying the visual distortion of a decades-old news broadcast on CIA-sponsored mind control, Jones gives new meaning to McLuhan’s chestnut, “the medium is the message.” Samuel M. Delgado and Helena Girón’s Neither God Nor Santa Maria proposes an analogous relationship between distressed footage and occult possession by layering intimate images of an old woman on the island of Lanzarote with archival audio interviews describing the island as a former bastion of witchcraft. A strangely poignant bit of ethno-surrealism, Delgado and Girón’s embrace a lost way of life without recourse to naturalism.

Still from “Psychic Driving.” Dir. William E. Jones

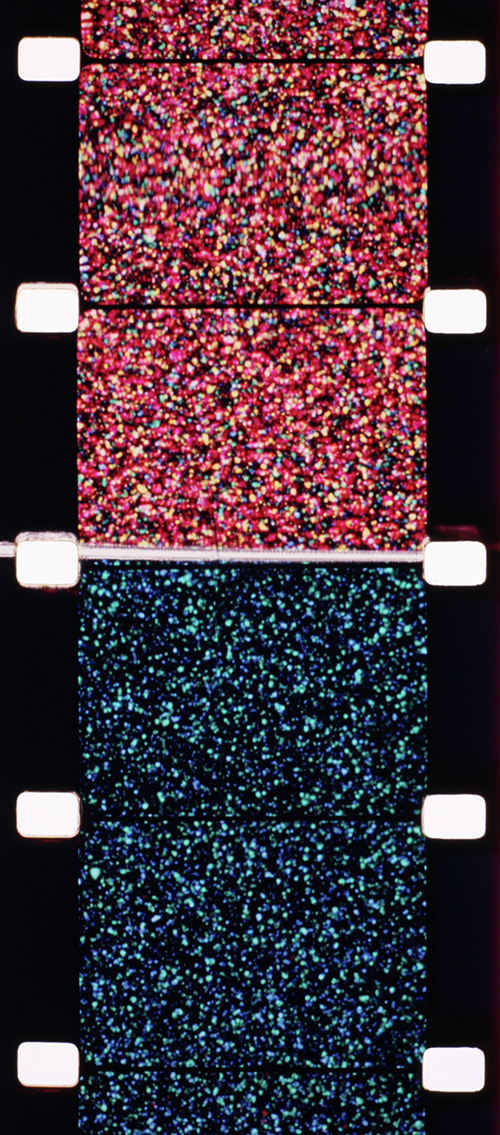

Several exceptional abstract works dotted the shorts programs, starting with Paul Sharits’ surprisingly subdued 3D Movie (1975). A shelved experiment recently recovered by Anthology Film Archives, 3D Movie’s dance of red and blue dots reduces the three-dimensional apparatus to its essence. On the maximalist side of things, Daïchi Saïto closed the final program with the electrifying Engram of Returning. Filmed in 35mm CinemaScope, Saïto boldly elects to leave the widescreen image black for much of the film such that flashes of color and texture seem to be firing directly into the audience’s synapses—an effect heightened by the micro-rhythms of Jason Sharp’s score for saxophone. No less revelatory was Charlotte Pryce’s Prima Materia, a characteristically tactile encounter with the firmament of celluloid and, by extension, all bits of matter illuminating the thresholds of perception. I look forward to seeing a group program in which Pryce’s pointedly modest work is given the last word.

Still from “3D Movie.” Dir. Paul Sharits.

For pure ecstasy, nothing that compared to a long sequence deep in the third part of Arabian Nights during which smeared black-and-white footage of the Brazilian psychedelic rockers Novos Bainos is superimposed upon a colorfully imagined troupe of Baghdad bohemians—a characteristically bravura gesture from this hugely ambitious, life-affirming work. Miguel Gomes adapts Arabian Nights’ proliferating structure to the age of austerity. In his version, Scheherazade appeases the king with an anthology of anecdotes drawn from Portugal’s front pages and back alleys circa 2012-2013. The pageantry ranges from shipyard strikes to farcical lampoons of the European Bank; a frigid New Year’s Day swim to a dog encountering its own ghost; a census of the lives contained in a high-rise apartment to the ballad of a reprehensible fugitive who nonetheless becomes a folk hero for having bamboozled the authorities; an elegant meditation on cultural transmission in the form of a documentary study of chaffinch song competitions to a dramatized courtroom scene collecting some of the odder crimes to appear on Portugal’s blotter (a kind of burlesque of Abderrahmane Sissako’s 2006 masterpiece, Bamako). A born surrealist, Gomes opts not to resolve the tension of lyricism and activism but rather to give the kaleidoscope another turn. I’m left in wonder at the energy holding it all together, for the real mystery of this Arabian Nights is that a film so despairing of contemporary events should also be so prodigiously inventive, so brilliantly assured of the necessity of storytelling. I would give it another six hours of my life in a heartbeat.

Still from “Arabian Nights.” Dir. Miguel Gomes.